We focus today on Israeli social solidarity. It was during the Judicial Reform “process,” of course, that the deep divisions in Israeli society became headline news. Many, including President Herzog, warned that Israel was heading to civil war. Ari Shavit, a leading Israeli journalist whom we’ve featured on our podcast, warned in his columns during that period that the social divisions in Israel would lead to a massive military attack on Israel.

He was apparently right.

Since then, one of the burning questions in Israel has been whether or not Israeli society has learned to transcend those divisions. There are those trying hard to create a different kind of discourse, and we point to some examples below, but there are also worrisome deep divisions—about, among other issues, drafting the Haredim and what sort of deal to make to get the hostages back.

We’ll look at each of those today. The Haredi issue we’ll look at through a Facebook posting by Rabbi Ilai Ofran, who has some pretty clear things to say about the issue. As for the social contract and the hostages, we hear from Gideon Argov, himself an influential personality, and also the son of Shlomo Argov, whose attempted assassination in 1982 was the immediate cause for Menachem Begin’s invasion of Lebanon.

As we’ll see below from a description of Israel’s Lebanon war plans in 1982, not much has changed.

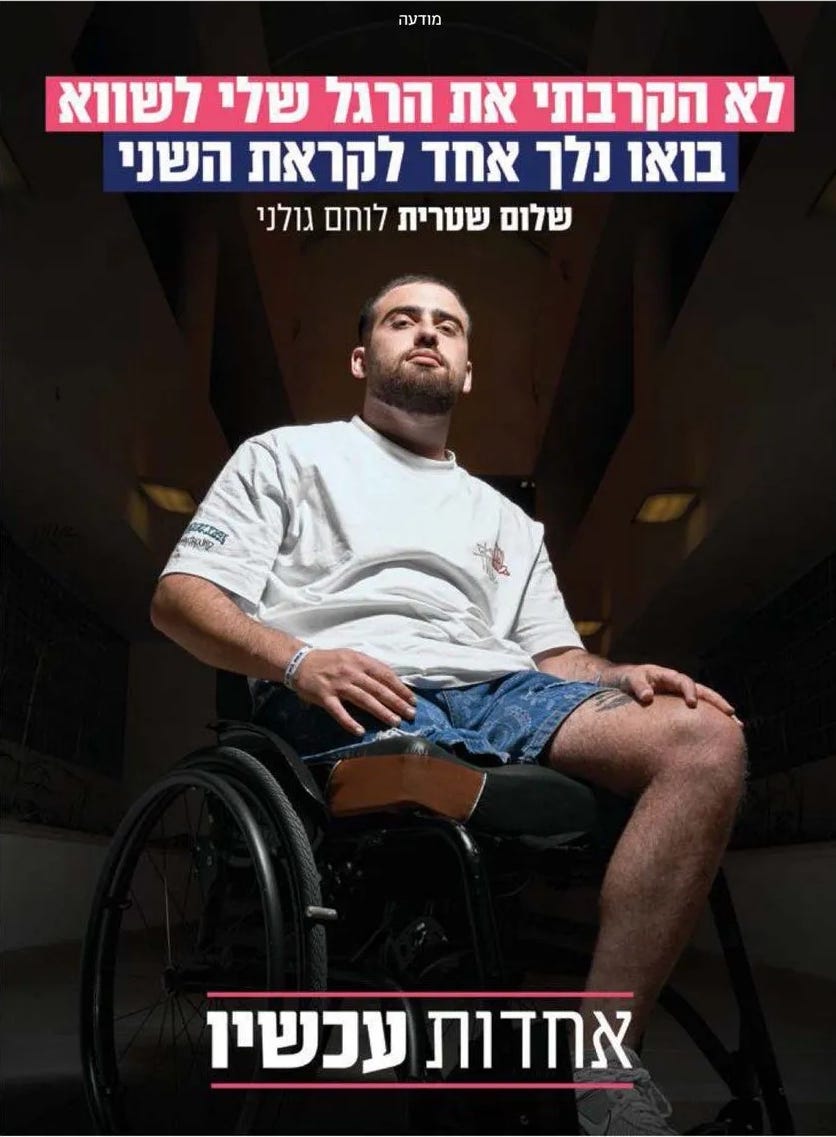

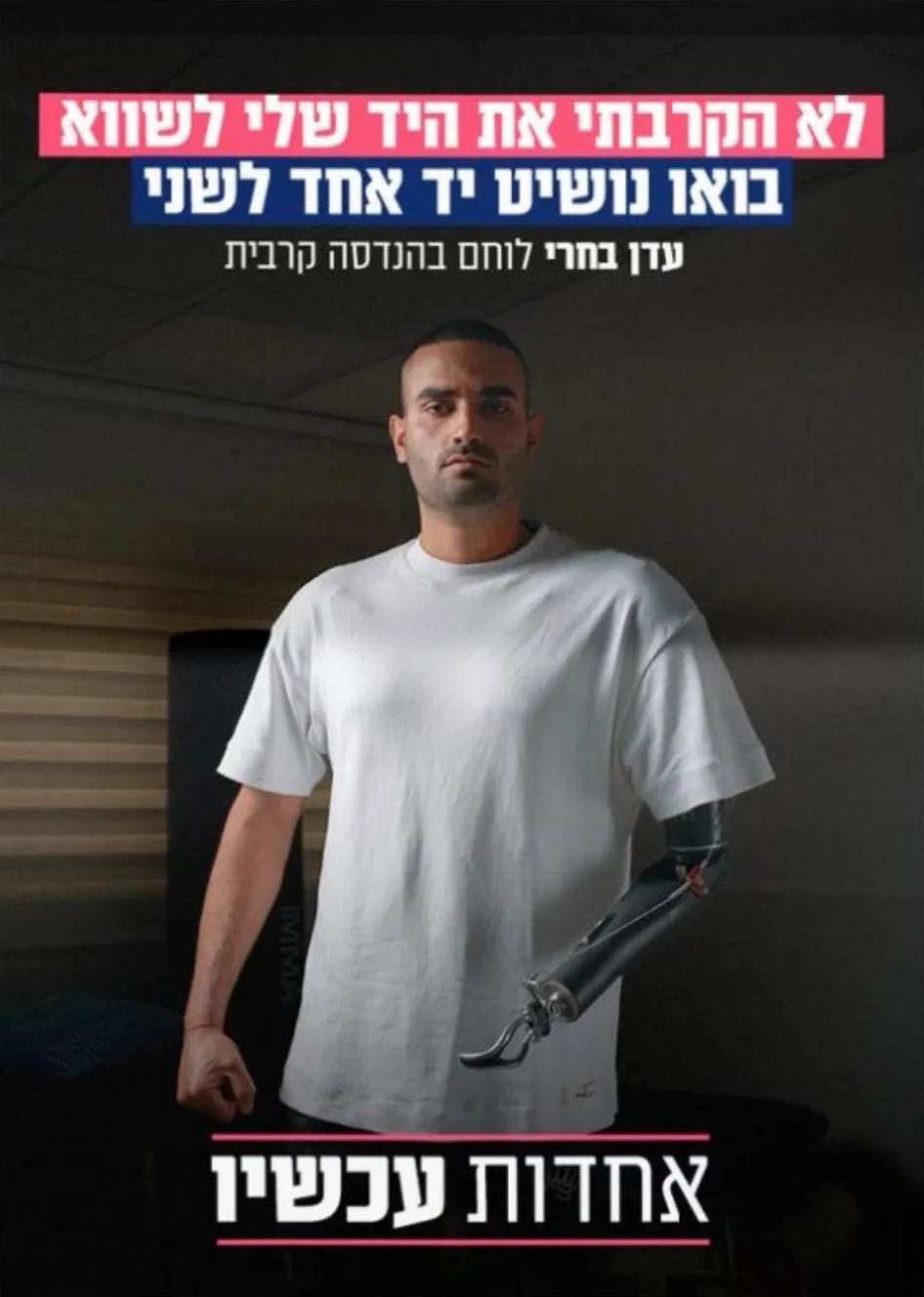

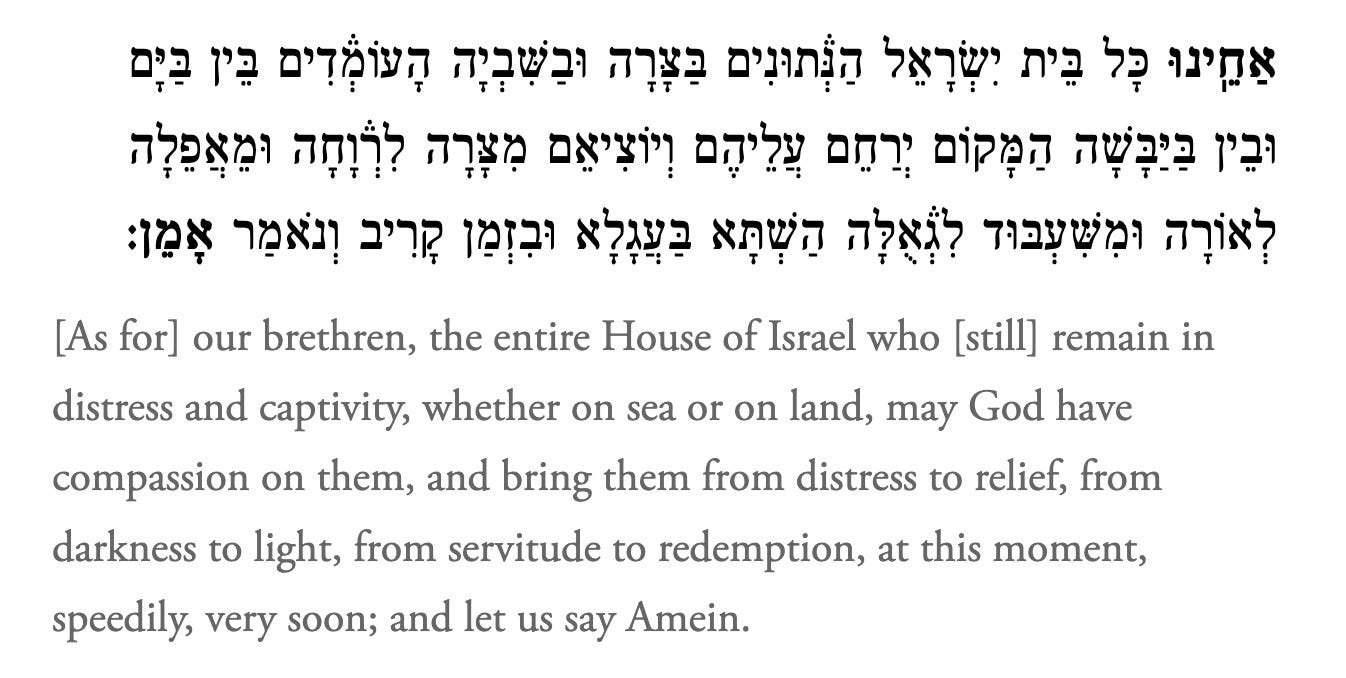

We begin with a social media and print campaign that has gotten some attention in Israel. The theme is אחדות עכשיו, Achdut Achshav, or “Unity Now.” With arresting images and harrowing phrases, they’re working hard to remind Israelis of our desperate need to bond together.

Here are three examples:

The three lines at the top of the poster read:

I did not sacrifice my leg in vain. Let’s walk one towards the other. Shalom Shitrit, a fighter in the Golani Brigade

At the bottom: Unity Now.

The three lines at the top of the poster read:

I did not sacrifice my hand in vain. Let's extend our hands to each other. Eden Bach'ri, a fighter in Combat Engineering

At the bottom: Unity Now.

The three lines at the top of the poster read:

It's permissible to disagree It's forbidden to stop loving Sergeant Major Shai Biton Hiyun.

And the last lines, tragically, read:

In their deaths, they commanded us to unite. Unity Now.

But posters can’t, on their own, change a political culture, and the ugliness of Israel’s political vitriol is back in the new, front and center.

Just yesterday, MK Nissim Vaturi, the Deputy Speaker of the Knesset, referred to the anti-government protesters as “an arm of Hamas.” The protesters responded that he was “both a fool and an inciter to violence,” but it will blow over. Calling Israelis with whom one disagrees “an arm of Hamas” is kind of how some parties roll.

There was also an ugly exchange in the cabinet, widely reported even though cabinet discussions are not supposed to be made public. Numerous Hebrew news sources reported that in the meeting, Bezalel Smotrich criticized IDF Chief of Staff Halevi for posting messages about the Haredim and the draft issue.

Referring to the theoretical rule that the army is supposed to stay out of political matters (which is essentially impossible for the Chief of Staff, who is by definition the bridge between the army and the political leadership), Smotrich said to Halevi, “This is a political issue and the Chief of Staff is not supposed to speak about it. I think that comments by the Chief of Staff are inappropriate.”

But Halevi, whose plans to resign are now well known, had no intention of taking it sitting down, and retorted, “The IDF was instructed by you to draft Haredim now. Take some responsibility. I know this [DG - the word “responsibility”] is an unusual word around here,” he snapped, an obvious reference to the fact that Netanyahu has refused to take any responsibility for the catastrophe that has befallen the staff. “… I will continue to recruit from all parts of Israeli society. The IDF needs soldiers.”

Smotrich then claimed again: “You are interfering in a political matter.”

Halevi snapped back, “I am not interfering, I am working to encourage the ultra-Orthodox to enlist. The IDF needs it for security.”

But, of course, the ultra-Orthodox have no intention of enlisting. And because it would endanger his coalition, Netanyahu has no intention of pushing the issue. So the army is pleading for soldiers, while the government is playing politics and non-Haredi soldiers continue to die on the battlefield.

In light of all this, there was a fascinating post by Rabbi Ilai Ofran, a well-known Orthodox rabbi, Israeli public figure, active on social media, an author and the head of a pre-army mechinah program.

In a Facebook post that has created a bit of drama in Israel in the past few days in modern Orthodox circles, Rabbi Ofran had this to say (Google translated with extensive revisions for style and background):

I'm not writing the following for the ultra-orthodox public who don't enlist. I have no expectations from them. Not even for the secular public, whom I'm not sure these questions bother at all, but for quite a few innocent and honest people in the religious-Zionist public, young and old, who have unwittingly adopted some ideas from the ultra-Orthodox message board. The percolation of these views into the worldview of the religious public is no less than an existential danger, which is why I am writing.

"We also believe that studying the Torah protects the people of Israel." Well, no. I for one do not believe it at all. To be honest, this is a fairly new ultra-Orthodox rant that was created in response to complaints about the shameful ultra-Orthodox draft evasion, to create the impression that they, too, are bearing some sort of burden for the country. It is almost impossible to find sources for this opinion in ancient literature, with the exception of a few legendary proverbs that were taken out of context (when the Talmud says "the Torah saves” (which meant there that the practitioner of the Torah was saved from transgressions, not from death).

We study the Torah because it is our life and the length of our days, not because it is profitable and not because we derive any benefit from it. The Torah did not protect the Jewish people for any problem in history, but this did not cause the Jews to stop studying with devotion. This idea that that we study for a purpose [DG - so we’ll be saved] within the Beit Midrash is sacrilege and contempt for the Torah. It turns the Torah into a tool, not a value.

"We also agree that we need a handful of Torah students who will be exempt from service" - well, no! I totally disagree with that. Enlisting in the IDF, especially during war, is a mitzvah. Just as it is unthinkable that Torah students would be exempt from observing Shabbat, or from kosher laws, so it would be unthinkable that Torah students would be exempt from conscription. To learn Torah from a draft-dodger, in my view, is equivalent to learning Torah from those who violate Shabbat in public, or from those who eat rabbits. It is true that there is an opening to include them in the minyan, because most of the ultra-orthodox in Israel fall into the halakhic category of "children who have been captured" [DG - and therefore were not raised with genuine Jewish values]. They may have a beard, and they know how to read Rashi script from books with red covers and golden letters, but this is not Torah.

"It is clear to everyone that you cannot recruit by force" - well, no! That is not at all clear to me. This problem will not be resolved through dialogue, agreement or compromise. Change will only happen by coercion, with severe sanctions not only on the yeshiva, political parties and ultra-Orthodox institutions, but mainly on the individual, man or woman, who chooses to evade. The ultra-orthodox learning society in Israel is a new creation that has no precedent in history and has no parallel in any Jewish community in the world. It was born as a result of the extreme conditions granted to it by the State of Israel, and it will soon become extinct in our days, when these conditions are abolished.

The Torah that was given to us at Sinai is a Torah of Life—it is supposed to guide our lives, and the righteous who live as a light, “even in their death are called ‘living.’” The Torah of the new Israeli ultra-Orthodox is a “Torah of Life” of a completely different kind—it preserves the lives of those who cling to it, by requiring others to die in its name in their place. It is a Torah that is redeemed by the blood of Jewish soldiers.

It is a Torah that is a drug of death.

What was fascinating to me about Rabbi Ofran’s post is that I hear from many people, including passionately secular people who do want the Haredim to serve, “Of course it will take time, and of course, it cannot be done by force.”

No, says Rabbi Ofran. Force is exactly what it will take, and it needs to happen now.

Every now and then we get a breath of fresh air.

In today’s podcast, we hear from Gideon Argov, whose bio appears below. In addition to his many accomplishments listed there, Gideon has a very personal connection to Israeli politics and history—his father, Shlomo Argov, was Israel’s Ambassador to England and was attacked by Palestinian terrorists, who failed to kill him, but who wounded him grievously.

Here’s a brief summary of the period as it appears in my biography of Menachem Begin, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul. It’s important to remind ourselves, as Israel may or may not be on the eve of a major operation in Lebanon, that operations in Lebanon have never gone as expected. Never.

While some members of his cabinet continued to resist, worried that the operation [in Lebanon] was unnecessary, Begin received wholehearted support from his defense minister, Ariel Sharon. Sharon had already become a polarizing figure in Israeli politics. In his short time as minister of agriculture, he had authorized the development of sixty-four settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He had also presided over the completion of fifty-four towns and fifty-six kibbutzim and moshavim (Jewish communal villages) in the Galilee, some of which were now under PLO fire. For Sharon, the emerging conflict with the PLO was thus both strategic and personal.

Despite their differences, Begin respected Sharon’s abilities as a soldier. Begin, in fact, had an abiding awe for Jewish soldiers in general, and he referred to Sharon as “the most fearsome fighting Jew” since the time of Judah Maccabee. If he was “the horseman,” Begin also said, Sharon was his “prize stallion” (albeit one with an unbridled, indomitable character).

Just as the Coastal Road attack had unleashed Begin’s first foray into Lebanon, an attack by a Palestinian splinter terror group on Ambassador Shlomo Argov in London on June 3, 1982 (almost a year to the date after the Osirak attack), contributed to the second. Though shot in the head, Argov did not die. He remained in a coma for three months; after he regained consciousness, Argov was returned to Israel, where he remained a permanent patient in a rehabilitation hospital, for life. (He died in 2003, at the age of seventy-three, having been hospitalized for twenty-one years.)

Begin had had enough of Jews being attacked, both in Israel and abroad. He called a cabinet meeting, and instructed Sharon and the IDF chief of staff, Rafael Eitan, to present “Operation Peace for Galilee”—a plan drawn up by the IDF that would establish a buffer zone deep enough into southern Lebanon to prevent further shelling and which would punish the PLO. Despite the fact that this plan conformed to the forty-kilometer limit that Begin had promised Israel would abide by, cabinet members were concerned by the operation’s length, scale, lack of international support, and public reception. Sharon promised the cabinet, however, that the IDF would not go near Beirut. Fourteen ministers voted in favor of the operation, two abstained, and no one was opposed.

Israel’s plan was risky for yet another reason—it depended on the political survival and cooperation of Bashir Gemayel, the head of Lebanon’s Christian Phalangist party. Lebanon at the time was mired in a civil war among Maronite Christians, Sunnis, Shiites, and Druze, all vying for power in a rapidly disintegrating country. It was this chaos that Arafat and the PLO had exploited as they turned southern Lebanon into their base of activity and a launching pad for terrorist activity.

Decades earlier, Jabotinsky had remarked that when two ships are sailing in opposite directions, each buffeted by the same storm, which ship would reach its destination was all a matter of the captain’s skill. Storms could be destructive, but they could also be opportunities.

Like his nemesis, Arafat, Begin saw in the Lebanese civil war a potential opportunity. Along with others in his cabinet, he hoped that in return for supporting the Christian Gemayel and his men in their ongoing conflict with Lebanon’s Muslims, Israel might even be rewarded with a peace treaty. If Gemayel could assert his power over Lebanon, Israelis would live quieter lives. But that meant staking the success of Operation Peace for Galilee on one major element—Gemayel’s success—over which Israel had virtually no control.

The operation was launched on June 6, 1982, just days after the Argov attack (and almost precisely fifteen years to the date after the start of the Six-Day War), with little fanfare. The expectation was that the operation would take several days, and initially, sophisticated coordination between aerial strikes and ground movements allowed the IDF to achieve its opening goals quickly.

But almost as soon as the operation began, Sharon began to tell Begin that more extensive goals for the operation were becoming necessary.

In the end, of course, the “operation” lasted not for a few days, but for eighteen years. And where we are with Hezbollah and Lebanon today is a bit of an indication of how successful it was—or wasn’t.

Interestingly, Shlomo Argov, who had an excellent relationship with Begin despite Begin’s being at the helm of Likud while Argov had a Labor background, was unhappy that his attack was being used as a excuse to go into Lebanon.

Today, we hear from Argov’s son, Gideon, about his father, and about his own take on Israel’s social contract, particularly as it bears on the hostage situation.

NOTE: There were a few instances in which the microphone got touched, leading to a bit of a “bump” in the sound. We’ve edited out what we could, and apologize for those we couldn’t remove.

We’re making this podcast available to all our readers and listeners.

Gideon Argov is managing partner and co-founder of New Era Capital, a Tel Aviv and Boston- based investment firm focusing on Israel-nexus early-stage technology companies. Gideon is also an advisory director of Berkshire Partners, a private equity investment firm based in Boston. From 2004 to 2012 he was President and CEO of Entegris, a global supplier of products used in the production of high-technology components and substrates. From 2001 to 2004 he was a Managing Director of Parthenon Capital, a private equity partnership based in Boston.

From 1991 to 2000 he was Chairman, President and CEO of Kollmorgen Corporation, a supplier of high-performance electronic motion control products. Gideon has served on the boards of numerous public and private companies.

He is the founder of the Shlomo Argov Fellows program for leadership in the public sector at Reichman University in Israel and serves on the International Council of the Belfer Center in the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He received his BA magna cum laude from Harvard University and his MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Gideon and his wife Alexandra have two daughters and reside in Newton, Massachusetts, and he has three grown sons.

The link at the top of this posting will take you to the full recording of our conversation; below you will find a transcript for those who prefer to read.

Some time ago already, back when I was working on my biography of Prime Minister, Menachem Begin. I got to the part of his life when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, and as a result of that, of course, came across what is a fairly well-known and tragic story, the story of Shlomo Argov, who was Israel's ambassador to Great Britain at that time, and who, on June 3, 1982, was grievously wounded in an attempted assassination. Shlomo Argov did not die immediately from his terrible wounds and spent many, many, many years in the hospital. But it's a tragic story that is very much bound up with Israel's history. Argov was born before the state of where it was created. He served in the Palmach, which was the elite strike force of the Haganah, and later on spent his entire life devoted to the state of Israel.

Many years later, after I'd already finished the book on Begin and moved on, I had the privilege of meeting and developing a friendship with Gideon Argov, Shlomo Argov’s son. Gidi and I have been friends for a number of years already. And as he visits Israel regularly, we try to find time to catch up, and these days, especially, to talk about his take on what's happening in the Jewish state.

He visited Israel just a couple of weeks ago, and we sat together once again at my home, and I asked him to do two things in our conversation. First of all, I thought it is really important that his father be known not for the attempted assassination, but for his lifelong devotion to the Jewish state. And I asked Gidi to talk to us a bit about his father, not only the horrifying events of June 1982 and their aftermath, but a lifelong dedication to everything that Israel stood for. And then I asked Gidi to speak about the challenges that Israel is facing today. And he had some fascinating things to say about the hostage crisis and what Israel's handling of the hostage crisis could mean for the social contract that lies at the very core of what the Jewish state is.

Gidi is managing partner and co-founder of NewEra Capital, a Tel Aviv and Boston-based investment firm that focuses on Israel nexus early-stage technology companies. He's also an Advisory Director of Berkshire Partners, a private equity investment firm based in Boston. He received his BA Magna Cum laude from Harvard University in his MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He and his wife, Alexandra, who is also a dear friend, have two daughters, and they reside in Newton, Massachusetts. He also has three grown sons.

I'm very grateful to Gidi that he took the time to be with us today. I'll just share with our listeners that there's a couple of points in the recording when the microphone got tapped on, so there's a bit of a loud noise at that moment. We tried to cut it down as best as we could without cutting into Gidi words. We apologize for that technical oversight but hope that you still take heart in the story of Gidi and his father, Shlomo, and I think, particularly, listen carefully to what Gidi Argov has to say about the social contract at the very basis of what Israel is. I'm very grateful to Gidi for joining us today.

So, Gidi, thank you very much for taking the time on a trip to Israel to get together and chat. We've been friends for a bunch of years, and when you've written things, I've read them with great interest. And it was relatively recently, within the last couple of weeks, I think, that for the first time ever, I saw you write publicly about your dad. And it may be that you've written before, I just haven't seen it. But it struck me that at this time in Israel's history, when we're thinking about so many different things and history is coming alive again and so forth, and it was a long time ago, it's, “megeiah lo,” as we say in Hebrew, he deserves, he merits, because of his devotion to the Jewish state and all that he contributed for a new generation of English-speaking people to know about the life and contributions of Shlomo Argov.

So, we'll come to the situation now and all of that in a little bit but honor us with some understanding and the picture the fullness of who your father was.

Well, it’s great to be with you, Danny, as always. The reason that I wrote the piece is related to the fact that I saw some obvious parallels between what happened in Lebanon 42 years ago and what is happening now to Israel. There were obvious parallels. I wanted to talk about them and talk about them in the context of my father and his experience. He was a eighth generation sabra. On his mother's side, the family was the Solomon family. They had come in the 1700s from Lithuania. His family was one of the first to live outside the walls of old Jerusalem in Nahalat Shiv'a.

But were they part of that old Yishuv religious clan?

They were in the old Yishuv. They were civic leaders. They were not all rabbis, but they were civic leaders. My father's great, great grandfather was Shlomo Zalman Zoref, my father's named after him, and he was the person who actually raised the funds for the building of the Hurva Synagogue.

That was destroyed and rebuilt.

That was destroyed and rebuilt. And oddly enough, a similar fate befell him as befell my father so many years later in terms of how he was attacked and ultimately passed away. But eighth generation Sabra, born in Jerusalem, and grew up in pre-Israel Palestine. Like most of his peers, went into the Haganah, the Palmach.

What year was he born?

He was born in 1929.

'29. Okay.

And went into the Palmach. He studied at the Gymnasia in Jerusalem. Most of his classmates went to the Palmach. One of the interesting things I experienced growing up was Independence Day in Israel as we all know, is a jarring transition from the Day of Remembrance, which is a difficult day, to a day of celebration. That's always a very sharp, jarring transition. In our family, the transition didn't really happen so much. I asked my father about that one day as a teenager, and he said, look, most of my friends in school were killed, did not make it through the War of Independence, and so for me, I always have a bittersweet memories of that period of time. And so, that's the environment he grew up in.

In the Palmach, he was in the Yiftach brigade. He was up in the north, mostly. He was injured. He was injured by a grenade, ended up in hospital for a period of time, still had shrapnel in him all these years later, but went back into action. His real purpose in life, what he wanted to do, was to actually be in the diplomatic service in Israel. It's difficult to imagine somebody wanting to do that so fervently today, but he wanted to be one of the first in Israel's foreign office.

Ended up, after the founding of the state, after the Palmach years, he ended up going to school in the US. He went to Georgetown. There are very few Israelis in Georgetown, a Jesuit school in 1950. At the Embassy in Washington, he met my mother. He worked as a, just to bring some money in as a student, he worked at the embassy as a security guard.

Was your mother also from many generations in Israel?

No, my mother came from Hungary as a child in the 1930s. Part of her family came over, or part of her family never made it over. And so, she grew up in Palestine, but she was from Budapest, from Pest, specifically. They met. She was serving at the embassy as Teddy Kollek’s Assistant Secretary in the office. They ended up, obviously, getting married. They got married in London because after his Georgetown years, he went to the London School of Economics and got a masters, and they were married there. And then, really, he had a 35-year career in the foreign office, and he started out working for the Prime Minister's office, Ben-Gurion was the Prime Minister, in a junior position, obviously.

And then he had a career which was long and incredibly, as it turned out, successful and fruitful. He opened up the first Israeli, if you will, offices or consulates in Africa, in Nigeria, and in Ghana, where we spent two years when I was a child.

Who would that have been? That would have been under Golda Meir?

No, Ben-Gurion was Prime Minister.

It was still under Ben-Gurion?

Yes.

Because we commonly associate the whole African push with Golda Meir, oh, she was the Foreign Minister.

She was the Foreign Minister for all those years, and BG was the Prime Minister, obviously. And so, we spent time in Ghana, Nigeria. I have very few memories of those years, but some unusual memories. I remember Moshe Dayan visited, I think, in Ghana, and his daughter Yael, who just passed away, unfortunately, came with him. She was a teenager about to go into the military. And I remember as a, literally, one of my first memories is having a bath from Yael Dayan, which was crazy. We went to New York after that…

She was an extraordinary person, we should just say.

She was. She actually was a feminist leader at a time when there were a few feminist leaders of her caliber in Israel, and she should be honored for sure. We then went to New York for three years. My dad was in the consulate. He was consul in New York, not consul general, but consul responsible for all the relationship with the Jewish community, actually. He made some very good friends during those years who stayed with him for a long period of time. Many, many years later, when he was in hospital after his injury, one of those friends, Isaac Stern, who we met in New York and became a good friend, when he came to Israel for all the 19 years that my father spent in hospital on Mount Scopus, he used to come and come to dad's room and take out the violin and play for dad. It was obviously quite an emotional thing to watch. So, he made good friends and allies during that period of time. From there, back to Israel, and where he headed up the Hasbara section, if you will…

Telling our story.

Telling the story, the narrative of Israel, yes. Then he went on to Washington, where he was the number two to Yitzhak Rabin. So, the Six Day War was an important war in Israel's history from many standpoints. In our family, it actually caused us to go to Washington because dad was asked to be the liaison between the foreign office and the high command in the army headquarters, many floors below a building in Tel Aviv. During the Six Day War, he spent a month there. Very close proximity to, obviously, Rabin, Weizman, the key decision-makers at that time.

Ezer Weizman, obviously.

Ezer Weizman, yes. He was a young diplomat, but he became close to Rabin. I remember he came back from that war after a month being away. He had lost a lot of weight. He was never a big... He was a very tall, strapping guy, but he was not overweight. He lost a lot of weight. He was exhausted after that experience and told stories about how close Israel thought it was to “hobran beit shlishit”, to a destruction of the third temple. And because of that, Rabin asked him to be posted, asked the foreign office to post my dad to be his minister, his number two, his Deputy Chief of Mission in Washington.

Those three years in Washington were…

Which were which years now?

1968 to '71. And they were interesting years because a lot of things happened. The US became a major arms supplier to Israel during that time. The first deliveries of F-4 Fantoms and other weapons. Many challenges with the Roger's Peace Plan at the time. Nixon was the President. Kissinger was the National Security Advisor. Then he became the Secretary of State. Al Haig was the National Security Advisor. Al Haig, at one point, he was a very informal man for a general, and at some point, my dad asked him, “how would you like me to call you?” And Al said, “just call me Al”. Not like the Paul Simon said, call me Al. And so, he said, “can I call you Shlo?” Which is not... nobody would call anybody called Shlomo, Shlo, but that was his diminutive question. So, those were fascinating years in Washington, and then after that, he was nominated to be ambassador in Mexico. We went to Mexico for three years, back to Israel. And then finally, I was no longer within the family, I was in the military, but they were in the Hague for three years. He was ambassador to the Netherlands, and finally to London, where he was nominated to be ambassador by Moshe Dayan, who was really a friend and someone who dad had served under in the Palmach, and who he felt close to from a policy standpoint as well. Dad was by no means a left-wing person. He was a very security-minded civil servant who had experienced war and thought that Israel's position needed to be secure, and it needed to take whatever steps necessary to do that. So that was his career.

On the 3rd of June of 1982, he was unfortunately attacked by terrorists coming out of the Dorchester Hotel in London and ended up, unfortunately, being paralyzed. He was shot through the head, surviving, paralyzed from the neck down, living as a quadriplegic for the next 19 years in Hadassah in Mount Scopus, able to speak, able to have a conversation, but not able to really function physically. And so, he couldn't feed himself. It was not a good existence in every way. That's the story.

At a certain point, he lost his sight also, right?

He did not lose his sight. He lost part of his sight. He was not able to read, but he did not lose his sight. He passed away in, I want to say, 2002, I believe. So, that's the story. Everybody in Israel has a story. It's not unusual for, especially in today's world. There are so many difficult and horrible stories, hostages being held in Gaza, people being killed in this war. So, everybody has a story in Israel. It's just that ours is a bit different.

Yeah. I want to come back to one thing about, well, about the injury indirectly, which is that when I was working on my biography of Menachem Begin, was really the first time that I had read a lot of things about your father, both before the attack and then subsequent to it. And correct me if I'm wrong, but my understanding is that he and Begin had quite cordial relations relationship and liked him and respected him. But yet when Begin, which he did, used the attack on your father as the trigger point for sending Israeli troops into Lebanon, in which would become the first Lebanon War, which would not end until the year 2000. We were in there for about 18 years. Your father, obviously grievously wounded, was very unhappy that what had happened to him was being used as a kind of justification for the war. Do I have that at all right?

I think you have that right. I think he was certainly very aware of the war, and it's hard not to be aware. He was actually in a ward at Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus, where the ward was absolutely full of soldiers who were being treated for grievous injuries that they suffered in the Lebanon War. So, everybody around was a victim of some terrible injury. He was very aware. And even though he was a very security-minded, sort of a bitchonist, in Hebrew, you would say, fashioned after Rabin in some ways, in terms of his viewpoints, he did not like the fact that this was used as an excuse, and he was sensitive to that.

Did he think the war itself was a mistake?

It's hard to… the war in retrospect, the war was a mistake in the way it ended up. But when Israel went to Beirut, and occupied Beirut, I think that caused him to have some serious doubts, very serious doubts.

Even though he was a very security-conscious person.

Yeah. Because it was, let's call it, it was occupying an urban area with hundreds of thousands of people in a crowded place and hoping for a good outcome. That's not a good recipe for anybody. Not then and not today.

Well, we're going to come back to today. I mean, in retrospect there, though, when it comes to Beirut, specifically, that kind of did work, right? I mean, we got Arafat out along with the command of the PLO, and off to Africa they went. Obviously, he didn't stay there forever, and that story comes back. But again, obviously, the Lebanon War, retrospectively, obviously not a success, to be very kind. But the actual attack on Beirut, even though it was very controversial at the time, and even though it exacted a huge, I don't know how big, I actually don't know the numbers, but clearly there was a lot of civilian casualties. It wasn’t a failure.

No, it wasn't. But it was not a failure in a tactical sense, and strategically because Arafat left and went to Tunis with his folks. But it had purpose. It had a clear objective. And once that objective was attained, Israel actually withdrew from Beirut. That is true. That is true. So, there were clear objectives set. But then overall, this was what I meant to say, overall, 18 years was a long time. Ultimately, we all know that Israel withdrew. There was a very successful protest movement called Four Mothers. That was what really brought about to some great extent Israel's rethinking of its venture in Lebanon. And lest we forget, Hezbollah is in some ways a direct result of that experience in Lebanon. It did nothing to stop Hezbollah. In some ways, it created Hezbollah.

Okay, I want to come back to this notion of the Four Mothers because it's one of the examples of a populist movement. I mean, literally, at the beginning, people thought these four women were actually crazy. They would stand at intersections, and they would just simply say, It's not worth my kid's life. And people would honk at them and say all sorts of nasty things to them. It obviously brings back very recent memories and very current memories. But over the course of time, they got traction. Over the course of time, the movement grew, and they were clearly one of the pivotal reasons for Israeli public opinion to turn so starkly against the war, and then eventually getting out in 2000.

Now, that happens under Ehud Barak. Ehud Barak runs in 1999, makes three promises, as many of us remember, get the boys out of Lebanon, peace with Syria, and peace with the Palestinians. The first, he did, although the retreat was anything but glorious. Syria never happened. And if the Palestinian thing had happened, we might not be where we are today, but they were not interested. And in fact, when faced with a choice, they went to the second intifada between 2000 and 2004. I don't think you can blame Ehud Barak for that particular part.

But let's come to today. I mean, because you grew up in such a diplomatically connected household, every time you and I talk and we talk about somebody, I say, oh, do you know that person? You say, yeah. I think you're being very modest. I think you know a tremendous number of people. The first time you and I met, actually, we were both sitting, we were meeting up, and I was at a different meeting with the head of the Commanders for Israel’s Security, and you were coming in, and everybody knew everybody. You know a lot of people. And I'm just, I think from your particular vantage point, having watched through the eyes of the tragedy of your family, that Lebanon war unfold, Israel fighting terrorism, Israel fighting in heavily populated areas, being very security conscious, you served in the army and so forth.

Talk to me today as an Israeli who loves this country, which I know you do, who is deeply devoted to this country, as I know you are, who's raised your kids to love this country. There's no ambivalence here about the state of Israel. Our listeners should understand. Talk to me about where your head is at now and where your heart is at now.

So, I think Israel is a miracle. I think that it's the most successful national liberation movement in a long time, first of all. That is what Zionism is. When my daughter's teacher at her school came in two days after October 7th and told the class, in a private high school in the United States, and was asked by a student, and she was in the 10th grade, asked to hold a discussion about the new conflict in Gaza. When the teacher said, that’s fine, kids, but I want you to know that Israel is based on something called Zionism, and that is a racist philosophy. And when he said that, my young daughter said, sir, that is not true. Zionism is a national liberation movement of the Jewish people. It’s a highly successful movement. Having said that, Israel finds itself in difficult circumstances today because Israel has been unbelievably successful in defeating every Arab army that has tried to attack it for decades leading up to the Yom Kippur, including the Yom Kippur War. Israel was successful in defeating a conventional Arab terrorist set of attacks that predates the state all the way through the Second Intifada at great cost.

And yet, Israel finds itself to be today in an interesting position because a lot of things have changed. What's changed? Number one, we've got a networked world, and our adversaries in the Middle East and beyond are networked and connected in ways that were not true in the past.

I noticed the photograph at the funeral of the Iranian President a couple of days ago, Raisi, and the photograph included the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, the head of Hezbollah, the head of Hamas, Haniyeh. These were all people sitting around the table somewhere near, I think it was in Tabriz or wherever the funeral was. They were not talking about the weather. So, we have none of these adversaries is capable of threatening the existence of the state of Israel. But they are working together.

You can add the Houthis into that.

You can add the Houthis, you can add the Iraqi militias, you can add the aid that is indirectly coming in from Russia. You can add North Korea. These are all involved entities. So, number one, their network, they're connected. Number two, we're in the era of asymmetric warfare. Anybody can buy I mean, not technically, but it's not difficult to create an army of drones and make them able to go great distances with payloads that are deadly and actually hit any target. That's doable today. Ballistic missiles are becoming cheaper to produce. All of these weapons of destruction have become more available, and they've become more available to non-state actors in a way that creates real challenges.

And so, it's a world where Israel needs alliances as well as military strength to actually confront this. I think that's a different world than we've existed in the past. Israel has always relied and been able to rely on the support of important allies. France, obviously, in the 1950s through the Six Day War, and much more importantly, obviously, the United States, which shares values, which shares a dedication to democracy and the rule of law, and which shares the ideals upon which it was founded, were in many cases a mirror of Israel and United States were founded on many, many similar ideals.

So, there's a natural affinity. By the way, my father studied in the United States. He was always cognizant, extremely cognizant of this very special relationship with America. He talked about it often. It's fair to say he loved America, he appreciated America, and he understood that Israel is reliant on the United States, but at the same time needs to speak at eye level with the United States, including being able to say no. The question is, when, in what way, and at what volume?

So, we find ourselves this hinge moment when everything's changed, and at the same time, there are possibilities that never existed before. If my father was alive today and saw, first of all, peace treaties with, obviously, Egypt, Jordan, the Abraham Accords, and the possibility of bringing in the Saudis and potentially others, because if the Saudis make peace with Israel, you've got Malaysia and you've got Indonesia, the largest Muslim population-wise country in the world, and potentially Pakistan coming in. You could absolutely transform Israel's role in the world, its position in the world, if that would happen. And so, a lot is on the table right now. And I think in many ways, it really does remind me of the opening lines of the... It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.

So, I want to come back. We're going to obviously touch on Israeli leadership today, and I want to get your sense of it. I think I have a pretty good sense, but I want to hear. And obviously, the Prime Minister is Benjamin Netanyahu, and I know that after your father had been injured, he was awarded, he got an award that was given in London, and Benjamin Netanyahu, he was representing Israel in some important capacity, also got an award that night. And you flew to London to accept the award on your father's behalf, and you gave a speech. And Benjamin Netanyahu flew to London to accept the award, obviously on his own behalf, and gave a speech. And I remember once you telling me your initial impressions of Bibi Netanyahu.

Well, look, it was, I think, the Jabotinsky Foundation. I think the award was called the Defender of Jerusalem Award. It was in London. And I had never met Netanyahu until that time, I did meet him then. I listened to his speech, and I was struck by his intelligence, by his eloquence, by the fact that he embodied the, at the time, leadership and creativity and devotion to Israel that I thought was extraordinary. I was absolutely, totally impressed by this person. I mean, he's about, I think he's seven years older than me, and he was very impressive.

Okay, we're in a different place in Israel's history. Bibi Netanyahu is in a very different place in his career. He will go for Saudi normalization. He won't go for Saudi normalization. We'll have to see. I've also heard you speak a bit, because actually, one of the issues that comes up in both these podcasts and these posts is the issue of the hostages. Interestingly enough, I put out a piece not that long ago. I think it was after the video of the tatzpitaniot, the spotters who had been kidnapped, and they were bloodied. It was horrifying. Not graphic in any way, but just heartbreaking for Israelis to watch and to see. I posted it and said something about it. A few people wrote me and said, they're Americans, I get lots of really interesting people writing all kinds of things, it is actually engaging and sometimes very fun. And this person wrote and said, this Israeli conversation about the hostages makes me insane. That was the word that he used. He said, you have no leverage over Sinwar. There's no reason he should give the hostages back. And if it meant stopping the war to get the hostages back, that would be a disastrous decision for Israel to leave Hamas intact. It's a tragic, horrible thing, but these people are part of the casualties of the war. Israel can keep trying, but that's all. From what I understand, correct me if I'm wrong, you don't share that view.

I don't. I don't share that view.

And you think it has something to do with the social contract. That's what I really want to talk about. What's happened to the social contract in Israel and what you think the relationship of the hostage issue to the social contract is.

There have been hostages in the past in Israel. We all remember horrific things in Ma'alot when kids were taken hostages, they ultimately were killed. They were, obviously, Gilad Shalit was for five years. We all know these stories. They're terrible stories. Here's what's different. What's different is the number of people, the fact that it occurred on sovereign Israeli soil, and the fact that Israel was founded on an ethos and credo that it is a place of safety, of safe haven for Jews, regardless of whether they are being persecuted elsewhere in the world.

And the social contract between a country and its citizens is different in different countries. In the US, it has to do about more mundane things like social services. In Israel, it's an existential social contract. It basically means, you are safe here, we will protect you. And if you are in danger, we will come and get you. And here you've got, now it's 120, the numbers go down every day as bodies are recovered, tragically, or parts of bodies are recovered. But there's 120 people, some dead, some alive. Apparently not a few alive, more than a few. And it's been seven months, eight months. It doesn't work in the Israeli ethos to not try and bring these people home at almost any cost, at almost any cost.

Okay, so Sinwar says whatever number, let's just say there's 40 alive, but you have to stop the war.

So, this is where it gets complicated, but I don't think it's I don't think it's beyond a Rubik's Cube. It is very complicated for sure. But look, let's think about the alternative. It doesn't make sense to subscribe to the idea that an ideology and a movement that is called Hamas can be eradicated. You cannot eradicate an ideology unless you have a better ideology in its place. Ask the Americans how that went in Vietnam, or Iraq more recently, or for that matter, the French in Algeria. It doesn't work. If you can't destroy it, you can certainly hurt it. And Israel has done a phenomenal job at great cost of really creating enormous pain and loss for Hamas, which is good and morally correct and the right thing to do. But if you're not going to destroy the movement, then how do you actually replace it with something better? I think that there are enough elements that have come together at a really interesting time, maybe an unprecedented time in history, that not pursuing them all the way to ground is not a good idea. What are those elements? They're all out in the open. It's not rocket science.

There is the prospect for the first time of peace with not just the existing peace arrangements, but also bringing the Saudis into the fold. That has been on Israel's list forever. It is huge, the Saudi family, this is the most interesting country in some ways in the Middle East. You have a young ruler who's incredibly ambitious, very talented. They are the custodians of the holy places. They're imprimatur, means everything as the Ibn Saud, family. And so if you can bring them into the fold, if you can bring all the hostages home, whatever there is, bring them all home, if you can cause an international group consisting of Arab and non-Arab participants to be, in effect, deputized, to go into Gaza and set up not just a pier that's delivering food off from ships, but also to get the civil service operating again, to clean the streets, to start a process of rebuilding an area where, listen, there are 2 million people living there. They're not going away. Mr. Ben-Gvir can keep wishing that they're going to go away and emigrate willfully outside of Gaza. It's not going to happen. So, those people have to have an infrastructure to live.

They have to have some hope of living a normal life and having kids and having grandkids. So, billions and tens of billions will have to be deployed to do that.

So, what if you had that money and you had those international participants willing to go in in some way, and not saying it's easy, and you could have peace with the Saudis, and you could bring all the hostages home, but you had to stop the fighting now to do that in some fashion. My view, it's not even close. You do it.

Okay. I mean, it's very compelling. I'm sure it's going to make a lot of people wrinkle their brow, and that's great. That's what we're trying to do. We're trying to actually get people to think out of their comfort zone, their own box.

I want to ask you one last thing by way of beginning to wrap up. You're here all the time. I mean, right now you live in the Greater Boston area, but you're here all the time. And you're, obviously, as Israeli as Israeli can be, and you know a gazillion people here, and you're very networked, and your fingers entirely on the pulse. What gives you... this is obviously a difficult time, and we could list without any difficulty all the things that we know are wrong.

What gives you the most hope that when your daughters, who are end of high school, middle at the end of high school age right now, are your age, that there's going to be a vibrant, Jewishly interesting, democratic, secure Israel? What gives you that hope?

I think what gives me hope is the young generation in Israel, which is really an amazing generation. When you think about these are people who... the concern was that they were too interested in their own lives and their own economic success and didn't want to be activists because they were too jaded and too disappointed by the political system to become active. And the reality is exactly the opposite. We all saw what happened here after the 4th of January of 2023, and how young people became incredibly involved in, I'd say, the future of Israel, and particularly the checks and balances in Israel's political system.

In pushing back against the proposal of digital reform.

Correct. And you've seen that now in a different way, in the unbelievable bravery of Israeli kids, people who are... it's so sad. It's so sad to see sons and daughters of people our age now giving their lives. But they do so willingly, and they do so because they understand that it's their turn and there's no choice. And so they're doing so.

I think that generation has a unique opportunity because Israel has a number of unfinished things to do after this war, because there are a number of challenges that, in effect, have to take place. Here's the way I think about it. Israel has been the most successful…. it's been a miracle for 75 years. Startup Nation, ingathering of the exiles, a full-fledged democracy with minority rights, imperfect, the minority rights, a light unto the nations in so many ways. That was Israel 1.0. That Israel doesn't work in the same way. There is a need for an Israel 2.0. It needs to be rebuilt. What do I mean? One, the social contract has to be rewritten, and particularly the issue of national service, which has to be extended to a very broad set of the population and not just an increasingly focused on… the Haredim, but national service and also local service. There's no reason why Arab Israelis should not be doing local services in their communities as an option, for example. So that's one issue. Another issue, checks and balances, still not put to bed. That has to actually get resolved.

You mean the issue of the courts?

The judiciary, what are their responsibilities and obligations? Correct, this is a country with no Constitution, with no Bill of Rights, where, let's not forget, the executive and the legislative branches are one in the same branch because we have a parliamentary system. So, it's a really complicated story. It has to get resolved.

The issue of the physical boundaries of the state have to be resolved at some point because they're temporary, they're permanent, but they're not permanent. I mean, where does Israel end? Is still to be resolved in some fashion.

And then finally, the religion and the state and the relationship of religion to the state is an area that is absolutely requiring dramatic reforms because it cannot be the case, as it is today, for example, that millions of Jews in the United States who are Reform Jews are looked down on by a religious establishment in Israel that's dominated by Orthodox Jews who have certain rules and look at American Jews as second-class citizens, just to use a case in point. So that has to get resolved.

And the final thing is civil service reform. The civil service here, which, going back to my father, he was all about excellence, all about devotion to the state, and all about doing things the right way. And the people around him operated in the same fashion. Today, that is not the case. Anybody can read any one of dozens of reports about patronage, about corruption, petty corruption, but corruption, nonetheless, in government ministries. This is not the way Israel should run its ministries, and in some cases, municipalities. There's a need for major reform of the civil service and upgrading its capability. All those things are on the table. I think the young generation is up for it, and that's our challenge.

If that happens, which we hope and pray that it will, in a very terrible, horrifying a way, the unspeakable tragedy and catastrophe of this war might, down the road, be looked at as the wake-up call, a horrible price to pay, a heartbreaking price to pay that we're still paying and is still rising. But if the day comes, that your daughter is your age now, and she looks back and she says, that happened, that we built Israel 2.0 or 3.0 or whatever, maybe we'll be able to look back and say that 2023 in terms of judicial reform and 2024 in terms of the war, maybe we'll say those were terrible years, but they gave birth to, this is the Second war of Independence, this is the second time we're fighting a war from which a new Jewish state will emerge.

I completely agree with that. It's unfortunate, but if we want to be 100 years and 200 years into this amazing human experiment, that's where we have to go.

Your father's story is unbelievable. Your father's story is inspiring. It's a reminder, I'm glad you brought back the civil service at the very end because it is a reminder of how noble, devoted, principled the people who serve this state at that time were, your father prime among them. It's a real privilege to hear from his son about his story, his accomplishments, unfortunately, the tragic attack. But I know that you tell it with a sense of love and devotion to the country and love for him and his memory. I hope and pray that we together and our kids together, can build and rebuild a country that somewhere up there, he can look down and say, “that's the country that I was working for.”

Ken, yirtzeh. [Yes, he will]. Absolutely.

Thank you, Gidi.

Thank you, Danny.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Does Israel have a social contract? And if it does, who owes what to whom?