A land where students still want to think

What the launching of the University of Austin reminds us about Israeli society

It was the fall of 2014, shortly after a horrific summer of war with Hamas. Classes had started at Shalem College, where I work, and a few weeks after the start of the semester, I sat in on a class that all first-year students take, in which they read Homer’s epic war story, The Iliad. They were nearing the end of the book and were focusing on the pivotal battle between the two iconic warriors, Hektor and Achilleus.

Seated in a large square around the seminar table, the texts open in front of them, one of the students suddenly spoke, saying to no one in particular: “You know, the average Greek reader had to know that this was a totally stylized account of war,” and then he paused. “Because war is nothing like this.”

There was, instantaneously, a heavy silence in the room. No one moved, no one spoke. The instructor was wise enough not to say a word; he let the silence hang, ominously and painfully. These “freshmen” had just a few weeks earlier been at war. Sitting off to the side (and though it’s been more than seven years, I can still picture the room as if this scene had unfolded yesterday), I watched their faces. On the faces of some of the men, everything changed. Eyes stared off into the distance, and some, it was clear, were suddenly reliving moments that though seemingly from a different world, had suddenly filled the seminar room. A few closed their eyes and rubbed them.

There were also women who dabbed at tears. That summer, some of the students had had classes. Hardly any men showed up—many had been called up. And the women who did come to class arrived bleary-eyed, spent. They’d waited up all night to hear from a husband, a fiancé, a boyfriend, a brother. Then, when told that whomever it was that they were waiting to hear from had survived the day and was out of Gaza for the night (the bombing was so deafening that Israel regularly pulled soldiers out of Gaza so they could get some sleep), these women also got a few hours of rest. But they were haggard all day—and this went on for weeks.

I hadn’t thought of that scene in a long time, until the announcement of the creation of the University of Austin became a hot topic on social media over the past two weeks. Bari Weiss sent out an email to readers of her Substack column under the headline, “We Can't Wait for Universities to Fix Themselves. So We're Starting a New One.” And what followed was a fascinating column by Pano Kanelos, the founding President of the University of Austin.

The state of affairs in American academe that Kanelos described surprised no one, but the data is still staggering.

The numbers tell the story as well as any anecdote you’ve read in the headlines or heard within your own circles. Nearly a quarter of American academics in the social sciences or humanities endorse ousting a colleague for having a wrong opinion about hot-button issues such as immigration or gender differences. Over a third of conservative academics and PhD students say they had been threatened with disciplinary action for their views. …

The picture among undergraduates is even bleaker. In Heterodox Academy’s 2020 Campus Expression Survey, 62% of sampled college students agreed that the climate on their campus prevented students from saying things they believe. Nearly 70% of students favor reporting professors if the professor says something students find offensive, according to a Challey Institute for Global Innovation survey. The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education reports at least 491 disinvitation campaigns since 2000. Roughly half were successful.

The idea of the University of Austin is to create a genuine liberal arts college in America, a place where free inquiry and unfettered pursuit of truth are key. As news of the planned university spread, a number of people—including some of our graduates—wrote me to say, “They’re creating Shalem College!”

In some ways, that’s true. We are, as they will be, deeply committed to the great works of the Western tradition (and in our case, the Jewish tradition as well). They, like we, are committed to reading and learning from the works, thinkers and ideas that have shaped the world our students need to inhabit and will soon need to steer. They (I assume), like we, will assign the greatest and most influential works, regardless of the race or gender of the person who wrote them.

So yes, in some ways, the proposed new University of Austin does remind me of Shalem. But in many ways, it does not, precisely because these two colleges come to address very different social challenges. Students in Israel do not report professors for saying things that make them uncomfortable or that “trigger” them (a word no one uses in Israel).

That is not to say that no professor at any Israeli university and college ever crosses the line of what I might personally find in good taste, but it is to say that students who go to war don’t go looking for micro-aggressions.

They have real aggressions to deal with.

Nor do students in Israel protest the appearance of lecturers who have views of which they do not approve.

When we invited David Grossman, one of Israel’s greatest living novelists, to speak at Shalem, we knew that there would undoubtedly be students who strongly disagreed with his well-known left-leaning views (because our students, like our faculty, cover the entire political and religious spectra). But not only did we never even consider not inviting Grossman because of that, it never occurred to us that a single person would have objected (they didn’t, and if they had, it would simply have indicated to us that we had made an admissions mistake).

Instead, the room was packed with students and faculty left and right, religious and secular, and Grossman spoke to a hushed audience (I’ve linked to this video before, but if you haven’t seen it, it’s more than worth the few minutes). When the lecture was over and the crowd had begun to disband, a senior, who I happened to know leans pretty far right, walked briskly in my direction and stopped me. “I need you to know,” he said, “that that was one of the most important lectures or classes I’ve ever attended.”

He didn’t agree with Grossman; of that I’m certain. But he saw passion, commitment to Israel, devotion to the Jewish people, from someone on the opposite side of the political and religious “side of the aisle.” He’d learned—about Grossman, about Israel and about himself. He found the session valuable not because he agreed with what was said, necessarily, but because he had learned—to see things differently than he had before, to break preconceived perceptions.

He was more interested in listening than in protesting, more committed to learning than to taking offense.

Why has the campus anti-intellectual anger and intolerance that Kanelos describes not come to Israel? I’m not entirely certain. When our students read about what’s happening in the US, they’re more dismissive than anything else. I can no longer count how many students have said, in almost identical words, once they read about the culture of American campuses, “They don’t have anything that they’ve committed their lives to that they think is worth fighting for, so they have to create something.”

There’s obviously more to it than that, but that is certainly part of it.

So what was Israel missing that made us want to create a new college, to raise the eyebrows (and at times the ire) of the academic establishment?

Israel’s problem wasn’t that liberal education had become illiberal, but that liberal education had never taken root here at all.

Israel’s higher education system, while the envy of the world for its tech achievements, does not see as its purpose the creation of citizens for the Jewish state. As a result, Israel’s best and brightest are desperately ill-equipped to think about and respond to the most pressing issues that their relatively young nation faces.

Secular students at Shalem often feel robbed that after thirteen years of K-12 education, many of the classic Jewish texts we study are foreign to them when they arrive. Students who attended religious schools may have learned the texts but were rarely asked to think about Judaism as a rich and living civilization. What we seek for our students is that they see Jewish Civilization and Western Civilization as two grand civilizations, each with its canon of great, world-changing books, its array of pathbreaking thinkers, its cluster of ideas and questions that have shaped the way many people experience the universe. We want them to know that Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Locke, Hobbes and Rawls are in eternal dialogue with the biblical mindset, the rabbinic revolution, Ibn Gavirol, Maimonides, Mendelssohn, Kaplan and Soloveitchik.

We seek to build a shared language based on a shared canon that will allow Israeli citizens of very different backgrounds to relate to Israel’s challenges from different perspectives but through the same prism. We got into this business to model the sorts of bridges and the depth of meaning that only knowing one’s civilization(s) can build.

What we never had to work at was opening their minds. Open minds were what brought them to us in the first place.

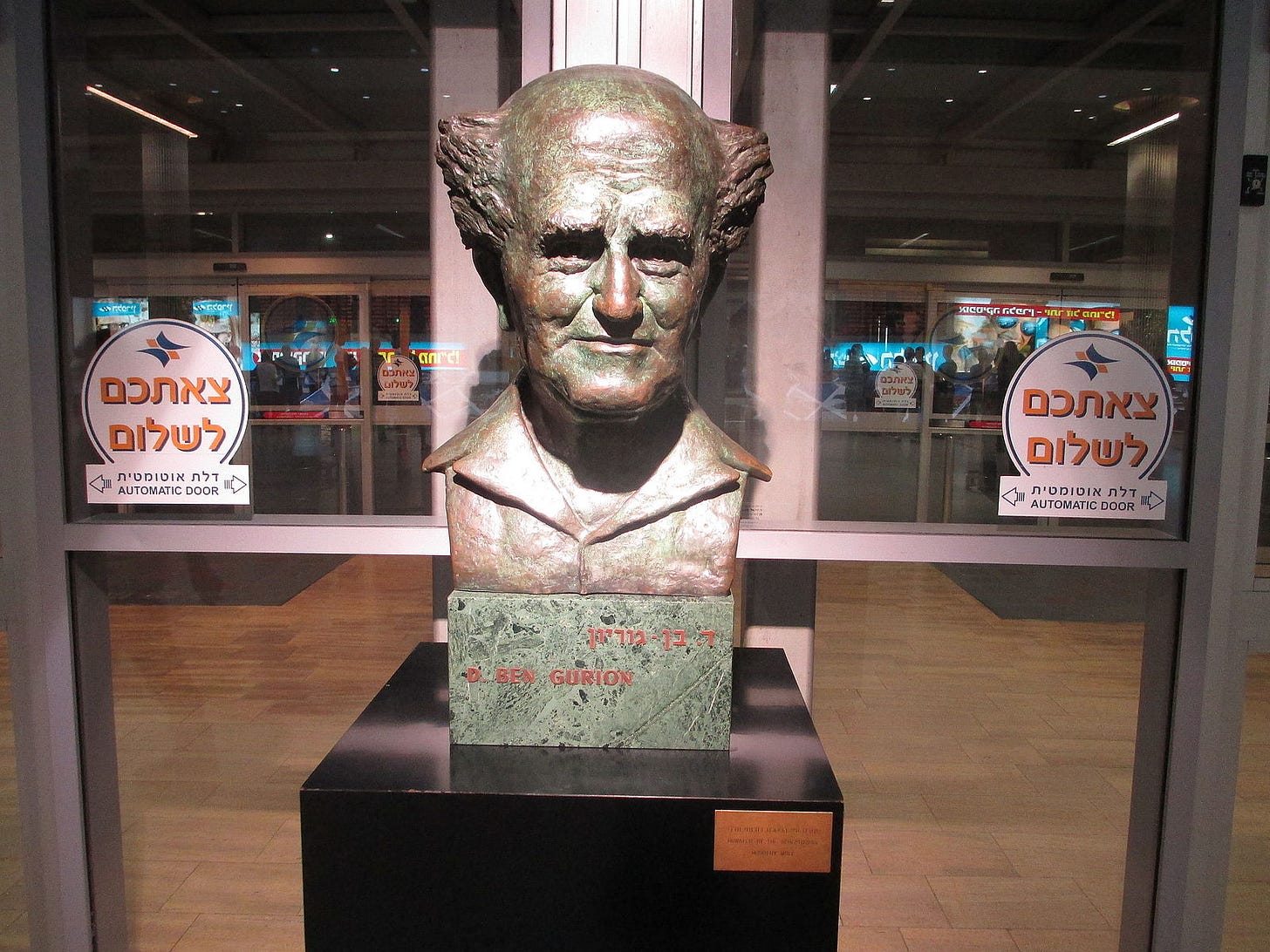

Upon arrival at Israel’s Ben-Gurion airport, it’s hard to miss the bust of David Ben-Gurion staring at you as you’re about to get in the passport line (and another as you leave the terminal). Even Ben-Gurion’s most ardent fans would have to admit that he was no simple fellow. The person who did more to found this state than did anyone else was hardly devoid of European, Ashkenazi elitism. Speaking about Bulgarian and Iraqi Jewish immigrants to Israel, for example, he said that they:

still do not constitute a people, but a motley crowd, human dust lacking language, education, roots, tradition or national dreams. . . . Turning this human dust into a civilized, independent nation with a vision . . . is no easy task.”

When he advocated that Ashkenazi and Mizrachi children be educated separately, he said he was worried that Israel would become “Levantine” and “descend” to be “like the Arabs.”

Hardly stuff that would pass today.

But no one in Israel is suggesting taking down Ben-Gurion’s statue, or any other statue of which I’m aware.

No one is suggesting changing the name of the airport, or the university. It’s not that Israelis don’t grimace when they hear some of the things that Ben-Gurion, or Golda Meir, or many others said. It’s that Zionism is still young enough that even if young Israelis don’t quite know who Nordau or Jabotinsky or even Ahad Ha’am were or what they said, they do have a sense that state-making was bound to be complicated, and that Zionism was always more a conversation than an ideology. They intuit that whatever they may think about this character or that, we likely would not be here without many of them.

If Israeli students have a challenge to overcome, it’s what they weren’t taught, not what they don’t want to hear.

Israel’s challenge is thus much more easily addressed than is America’s.

Jewish civilization, no less grand than Western civilization, is as much the inheritance of secular Jews as it is of religious Jews, and the Jewish state has sold them short by not teaching them what they need to know and feel in order to live Jewishly intellectually and emotionally satisfying lives. The Zionist conversation is the province of all Israeli Jews, and too many of them, through no fault of their own, lack even basic literacy in the texts and ideas that animated the founding of the country they are called upon to serve and defend.

The good news, though, is that altering an unwillingness to learn or to listen is virtually impossible, while filling in gaps in education is what the Jewish people has been doing for thousands of years. No one founds a college “just because.” Just ask Pano Kanelos and the team committed to getting the University of Austin off the ground. It’s a lot of work, and a risky undertaking. People found colleges because of what they’re trying to fix, what they’re trying to preserve.

The announcement of the launch of the University of Austin was an important moment for us—a moment to remind ourselves how different American and Israeli students are. Our students didn’t need a refuge from a society that can no longer listen, thankfully. They needed a college that would take their belief in this country seriously. A college worthy of their devotion and sacrifice, and one that would give them the tools and habits of mind they need to ensure that it continues to flourish.

In a way, all we did was what Israelis have always done. The Negev was dry? Those who came before us built the National Water Carrier. Israel had no natural resources? They turned human ingenuity into a national resource. We couldn’t depend on any ally to be entirely steadfast? So Israel created technology to safeguard our future and our children.

Just like the founders of University of Austin, we saw something critical lacking in our society, something that we knew only a college could address. So now it was our turn, and we built a new one.

Israel currently has two recognized systems of law operating side by side: civil and religious. Israeli religious courts possess the exclusive right to conduct and terminate marriages. There is no civil marriage or divorce in Israel, irrespective of one’s religious inclinations. All Muslims must marry and divorce in accordance with shariya laws, all Catholics in accordance with canon law, and all Jews in accordance with Torah law (halakhah).

The interpretation and implementation of Torah law is in the hands of the Orthodox religious establishment, the only stream of Judaism that enjoys legal recognition in Israel. The rabbinic courts strenuously oppose any changes to this so-called status quo arrangement between religious and secular authorities. In fact, religious courts in Israel are currently pressing for expanded jurisdiction beyond personal status, stressing their importance to Israel’s growing religious community.

In our conversation, Susan Weiss (co-author of the book above and a relentless advocate of women’s rights in Israel’s religious system) explains how religious courts, based on centuries-old patriarchal law, undermine the full civil and human rights of Jewish women in Israel. The more we listen to her, the more we have to confront the question she often asks: Is Israel a democracy or a theocracy? Here’s an excerpt of our conversation.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.