Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

An Israeli soldier probably killed Shireen Abu Akleh — what should happen to him now?

No Israeli I know wants that soldier prosecuted, and here's why.

A long time ago, back when our kids were much younger and in the army, we got a call that I still remember vividly. It came in that liminal moment between getting into bed and actually falling asleep. We were seconds away from being asleep when the phone shattered the silence.

“Hi, it’s me,” one of our kids said. I immediately got worried, even though he sounded fine. Why on earth would he be calling after 11:00 p.m.?

“You OK?” I asked.

“Fine,” he said. “I just wanted you to know that I’m going out tonight.”

That, I knew, did not mean that he had a date. He was still in training, but the unit was getting closer to being operational, and the training was getting very edgy.

What do you say when your kid calls you, telling you he’s about to go out for a night that’s likely to be terrifying, while you are in bed next to your spouse, between comfortable sheets, the temperature set just as you like it, the white noise machine a gentle membrane between you and the rest of the world, the black-out-drapes affording you the perfect dark you like? You’re about to nod off, and he’s about to … you know that you’ll never know…

Really, what do you say?

“Be very careful out there,” I said. “I love you.”

As soon as I’d hung up, my wife asked, “Who was it?” I told her. “What did he want?”, she asked. “Nothing,” I said. “He just called to say hi.”

But she knew I was lying. She’d heard me say “Be very careful out there.” Still, she intuited that there was a reason I was lying, that there were certain things better left unsaid before trying to fall asleep. So she turned onto her side, facing away from me, that blatant lie that simply needed to be told hanging heavy in the air, and went to sleep.

I would have, too, if I could have. But it’s on nights like those that you learn how slowly the numbers on a digital clock can move. “We’re going out tonight,” he’d said, so I decided (based on nothing, really) that when the night was over, so, too, would the danger end.

As I waited, hoping to fall asleep, I asked myself, “Why did he call? Why do we need to know tonight, rather than tomorrow, what he’s up to?” And then, I realized, of course, that he was scared. And he wanted to talk to his parents. They look all grown up, those kids, in uniforms (or sometimes, not in uniforms) and with helmets and night vision goggles and God knows what else, but they’re not all grown up. They’re still kids, in lots of ways, and so that we can stay alive, we ask them to do things that kids should never have to do. I was glad he was still enough of a kid to tell us, in not so many words, that he was scared. Because I wanted him still to be my kid, and more pertinent to that moment, because when you’re not scared, you’re not careful.

Eventually, I dozed off. When I woke up, I was certain that hours had gone by. It had to be at least 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., no? But it wasn’t. It was barely past midnight. And so went the night. I would doze, wake up, certain that it had been hours, but it had been only minutes—and there was a long, long night ahead.

Eventually, after what seemed an eternity, 5:40 a.m. came, and it was time to go to my early morning minyan. I got out of bed, got dressed, grabbed my tallit and tefillin, stuffed my phone into the back pocket of my jeans, and started out to shul. It was barely light yet; just a hint of the golden light beginning to reflect off all the Jerusalem stone on all the buildings. Exhausted, almost catatonic, I was walking to the synagogue, when I felt a buzz from the phone. I stopped in my tracks, read the message on the tiny screen:

Khazarnu. Hakol tov. “We’re back. Everything’s ok.”

Some fifteen years later, I can still feel the relief that flooded through me—as well as the exhaustion. What I really wanted was to turn around, go home, get back in bed and finally get the sleep that I desperately needed. But that wasn’t an option. There was still a kid at home who needed to be pried out of bed and sent off to school, there was a day of meetings—life had to go on. And I knew, of course, that we had no good reason to feel sorry for ourselves. We were hardly the only couple whose night had been interminable, who would stumble through the day because their kids, too, had been “out last night.” Hundreds of kids, I assume, had called their parents to tell them that they were scared.

I hadn’t thought of that night in years, until recently, when Israel acknowledged what we all knew pretty much all along—that it was likely that an Israeli bullet had killed Shireen Abu Akleh, the highly respected Palestinian journalist, four months ago yesterday. The world had immediately accused Israel not only of having killed her, but of having killed her intentionally, which Israel, of course, denied.

Among my friends, colleagues and neighbors, one thing was very clear while another was not. What was obvious to all of us, and remains obvious to me, was that no Israeli soldier intended to kill her. What was less obvious was the question of who killed her. Especially as analysis of who was positioned where began to emerge, it seemed quite possible that a bullet fired by an Israeli soldier had tragically ended her life. Why Israel took so long to acknowledge that, I do not know. There may have been good reasons, there may not have been.

Of course, Israel’s finally admitting that one of its soldiers may well have mistakenly shot her did nothing to calm the international winds. The Palestinians, on message as always, insisted that the killing was intentional. The Americans, always happy to hold Israel accountable to standards that they never apply to their own soldiers, suggested that Israel re-evaluate its rules of engagement.

(You may recall that when the United States, after months of denial, finally admitted that the killing of ten people, including seven children, by an American drone in Kabul had been a mistake, no one was surprised that that was what had unfolded. But no one suggested that the US alter its rules of engagement.)

Israel will, I’m sure, draw conclusions and perhaps even make operational changes—but not due to American pressure.

Prime Minister Lapid rightly rejected outright the American pressure for Israel to review its rules of engagement. Said PM Yair Lapid, as would any self-respecting leader—"Nobody will tell Israel how to protect itself.”

Reexamining the rules of engagement is not the only international demand that Israel is rejecting outright. It is also rejecting calls for prosecution of the soldier who fired the shot. The government has rejected that demand outright, to the relief of Israelis across the political spectrum.

(Is anyone calling for prosecution of those American soldiers who operated the drone? Of course not. This is about the Jewish state, as it always is.)

Why do Israelis not want the soldier prosecuted (assuming he can be identified, which is not at all unlikely)? Because Israelis think it’s okay for soldiers to shoot journalists? Because Israelis are unwilling to hold their military accountable for terrible errors? Anyone familiar with even the rudiments of Israeli history can recall numerous instances in which the people demanded that the army be held accountable. At times, rage over the army’s behavior has even toppled governments.

What, then, could it be? Why the resistance to prosecution here? Why the zero interest in even knowing the name of the soldier?

We’ll come back to that, but first, Colum McCann.

I read Colum McCann’s Apeirogon almost as soon as it came out, about a year and a half ago. It was a painful book to read (it is, in part, the true story of a Palestinian child killed by an errant Israeli bullet), but extraordinarily beautifully written. McCann is Irish, with no familial connection to either Israel or the Palestinian cause. But he plumbed the depths and the nuances of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict so deeply, and wrote about it so brilliantly, that I immediately recommended the book to a few people, among them a woman in our community whose views on books I always find thoughtful and provocative. I asked her to read it and to tell me what she thought.

Her politics and mine aren’t precisely aligned, but that, of course, is what makes talking to her and learning from her so engaging. (There are still places where people enjoy speaking with people with whom they can disagree.) And she also had kids in the army, though in different units from ours. She’s a probing reader and a deep soul. She makes me think. What more can one ask of a friend?

A few weeks later, we were at Shabbat dinner at her home, seated outside in the midst of Covid. I asked her what she thought of the book. She said she’d really liked it, but that despite the seemingly infinite numbers of sides of the story that McCann had covered (“apeirogon” is the name of a geometric shape with an infinite number of sides), he’d missed one important thing. I was stunned. He’s missed something? I’d read the book very carefully, engrossed in the gorgeous writing and the depth of the research, and I hadn’t noticed anything glaringly missing.

I was about to ask her what it was, but she got up to go into the kitchen for something. While she was gone, I tried to imagine what McCann could possibly have left out. I came up with nothing.

When she got back, the rest of the table was engaged in some other conversation, and she and I were the only two not involved. “So, what did he miss?” I asked her.

She stopped, and then said quietly, “He missed how scared our kids are.”

She was so right. Photographs often show our kids in uniform, armed, in armored vehicles. But they’re not always in the vehicles, the vehicles are not impregnable, and inside those vehicles are our kids. They are, for the most part, not only not bad kids, they’re good kids. They’ve been asked to do what they do so we can live. So we can sleep. So their younger siblings can go to school, so this country can be.

So they do it—but they’re often terrified.

I have not heard a single Israeli say that it does not matter that Shireen Abu Akleh was killed. I assume that some care more, some care less. But in my circles, every single person I’ve spoken to believes it was a horrific tragedy, but not one that should be prosecuted.

In contrast, when Elor Azaria shot an already subdued Palestinian in Hebron in 2016, even a former General and former Defense Minister argued that the behavior was outrageous and insisted that he needed to go to jail. I agreed. So did most of our friends, though not all. The ultimate sentence, after a trial manipulated in many ways by Bibi Netanyahu for political purposes was, in the minds of many, pathetically and unjustifiably short.

Why not prosecute the soldier in this new case?

Because what we parents know is that too often, while our kids have someone in the crosshairs of their sights, someone else has our kids in their crosshairs. And when that happens, who will emerge alive will depend solely on who shoots best … and first.

Hesitate for even a fraction of a second, and that other person can get you first.

We have to demand the very best of our kids, the best precision, the best discipline, the best intentions. But if after all that, a horrible mistake gets made, they need to know that the country that sent them into the hell of those streets is a country that will believe them, that will trust them, that will have their back.

Prosecuting that soldier, whoever he is, could bring that all toppling down. Prosecution would ruin his life, but what concerns Israelis even more is the possibility that fear of prosecution for a mistake, no matter how grievous, might lead soldiers on raids to hesitate at precisely the wrong second before they take the shot. Sometimes that will be a good thing. Sometimes it will be irrelevant. But sometimes it will mean that they will not get home for Shabbat—that they will never be home for Shabbat.

In my circles, at least, most of us now have kids way beyond army age; in fact, some of us have grandchildren who not that long from now will be of army age. So here’s what we already know. Our grandchildren, like our children were, will be terrified. Their parents (our kids) will also have sleepless nights. It’s heartbreaking to imagine our own kids going through the nights that we did when we were young and they were the soldiers. But they will.

Yet to imagine the worst is, well … unimaginable. No one talks about it, and everyone is terrified of it.

No one I know imagines for a second that whoever-he-is intended to kill an innocent journalist. We all truly believe that in the fog of war, and yes, in the fog of fear, he took a horribly mistaken shot.

If you have not watched the body cam footage of that raid, you absolutely should – it gives you a sense of how exposed they are, how vulnerable they are.

It’s a horrible, demoralizing, callousing way to live. For that soldier, as he knows who he is, and he’ll have to live with that shot for the rest of his life. But it’s also horrible, demoralizing, callousing for us, for our kids, for the Palestinians. It’s horrible in countless, endless ways, which is why Apeirogon was the perfect title for McCann’s book.

(Why this will go on for a long time we discussed in a different, recent column.)

Until things change, which is not about to happen any time soon, innocent people on both sides are going to die. Kids will be turned into soldiers, but all the equipment and uniforms notwithstanding, they’re still going to be kids, and they’re going to be scared. We want them to be honorable, moral, caring. But we also want them to come home. We don’t want them living under the fear of prosecution for honest mistakes, prosecution born of international pressure, because if they do, the time may come that they hesitate for a millisecond, and then it could be too late.

Whatever hopes my wife and I had, when we moved here 25 years ago, that our kids’ kids would not go to war, have long since died. We’ve given up the hope that they won’t. We have given up on the hope that they will not call their parents periodically and say something like, “I’m going out for the night.”

What we have not given up on, though, and never will, is that this is a country that will do everything it can to to make sure that in the morning after that call, our kids get a text on their phones from their kids, like we did, and hear what they’ve been waiting all night to hear:

Khazarnu. Hakol tov.

For all they’ve already done, for the people they are, this country owes them that.

The international reaction to the tragic death of Shireen Abu Akleh was part of a seemingly endless international attack on Israel’s morality and legitimacy. That all bears note, but so, too, do the extraordinary efforts of some people in the Christian community who are working tirelessly to bring the Christian world closer to Israel, to have young Christians learn to see Israel in all its complexity.

Later this week, we’ll meet Scott Phillips, who heads an organization called Passages. Our conversation which will serve as a much needed reminder that singled out though it may be, Israel is far from alone.

That podcast will be posted on Wednesday, as always, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

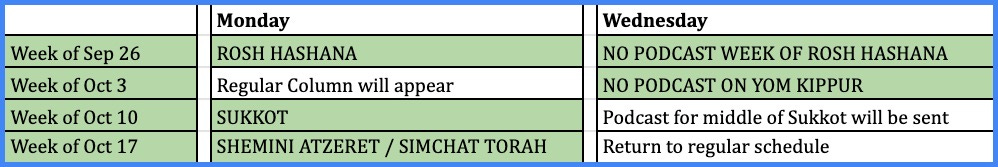

With the holidays coming up and many of them falling on Mondays (our column day) and Yom Kippur on Wednesday (podcast day), here is the tentative schedule for Israel from the Inside for the weeks of the holidays:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Its not just the "kids" who face incredibly fearful situations -- I was a 30-something reservist who on a couple of occasions found myself with a handful of guys in the midst of an almost riot of several hundred arabs wondering if I needed to use my rifle in order save my life or if firing my rifle would touch off an actual riot. For those armchair quarterbacks raised on Hollywood movies and TV shows who know when trouble will break out because the background music changes, gets tense and sometimes characters give long soliloquies ... real life is a whole lot different ... very hard to predict the next 5 minutes.

"What did he leave out?" A question not just for McCann, but for Gordis. As much as I am a fan of Daniel Gordis, what he left out that this was not just a "fog of war" situation. That this was a prominent journalist clearly marked as a journalist and not standing near anyone firing a weapon. And, critically, that Israeli soldiers in the West Bank of late are not consistently the moral force of yore, but include soldiers and commanders who believe it's OK to beat up, harass and maybe threaten the lives of other Israeli Jews whose politics they think are too leftist, much less Palestinians, much less a prominent journalist who exposes misconduct. I am not, here, arguing about the morality of the occupation or even the morality of this specific mission. I am saying, in this specific instance -- not in general, in this specific mission -- what Gordis leaves out is the evidence and context that suggests why this was intentional. I don't know that if means prosecuting one soldier or not. I do know that examining the rogue behavior of too many Israeli soldiers -- which alarms many patriotic Israelis -- could and should be the lesson here, beyond what one soldier did. It's a shame that Gordis put his thumb on the scale of evidence.