Jewish tradition has it that there are several “new years”. As the first Mishnah in Tractate Rosh Hashanah puts it:

The four new years are: On the first of Nisan, the new year for the kings and for the festivals. On the first of Elul, the new year for the tithing of animals. On the first of Tishrei, the new year for years, for the Sabbatical years and for the Jubilee years and for the planting and for the vegetables. On the first of Shevat, the new year for the trees.

The function of each of these new years doesn’t matter for now. For the moment, what strikes me about that Mishnah is that were it being written today, there would likely be a fifth “new year” added: the date that we began counting anew the soldiers, security personnel and victims of terror of the past year. That day is Yom Hazikaron, Remembrance Day for Fallen Soldiers, which Israel marked two weeks ago.

This “new year” has gotten off to a very bad start. The days leading up to Yom Hazikaron were a depressing way to end the year just concluding. On May 22, four people were killed in a ramming and stabbing terror attack in Beersheba. Then, on March 27, two soldiers were killed in a shooting terror attack in Hadera. Two days later, on March 29, five people were killed in a shooting terror attack in Bnei Brak. On April 7, three civilians were killed in a shooting terror attack in Tel Aviv. And on April 29, a civilian was killed in a shooting attack at the entrance to Ariel.

Any hopes we might have harbored that the new year would herald something different were quickly dashed. On May 5, just as Independence Day was ending, three civilians were killed in a gruesome axe terror attack in Elad.

(We don’t often enough think about the wounded survivors, who in this case, according to medical personnel, have skull fragments in their brains from the axe, in addition to deep axe-wound gashes in their faces and more. Both victims face multiple additional surgeries, years of rehabilitation and the degree to which they will have permanent cognitive damage is not yet known. It takes a certain kind of hatred to look a person in the face and pound an axe into them—sadly, that hatred is in no short supply.)

Then, on May 13, Sergeant Major Noam Raz died after succumbing to wounds sustained during an IDF raid on a terror suspect’s home in the West Bank.

If the rate does not slow down, this could Heaven-forbid be a new year of hundreds of casualties, with countless parents’, spouses’ and children’s lives ruined. For an array of reasons, it feels far from over; the region is a tinderbox, and there’s no knowing how this is going to unfold. To many of us here, it feels like something is about to blow. Hopefully, we’re entirely wrong.

Strange though it may sound, the horrifying toll of dead and gravely injured may not be the most problematic dimension of these past weeks. After all, we’ve faced terror since before the state was created. Yet what always enabled Israel and Israelis to face those challenges was resolve born of a sense of shared purpose, a common destiny. Even in the face of political and religious divisions, which we have aplenty, we knew how to come together when it mattered.

In that spirit, moments like Yom Hazikaron were considered sacred. The ceremonies were sacrosanct, and no matter what one thought of the political leadership of the moment, it was expected that everyone put aside their person grievances in order to be part of a national mourning that was greater than even their limitless pain—and perhaps even more importantly, to let the nation grieve. For the most part, that has worked.

Not this year, though.

At the national ceremony for Yom Hazikaron, at which the Prime Minister spoke, Bennett was heckled, called a “traitor”, a “swindler” and a “rag” and forced to wait a full five minutes before he was able to begin his address. “Shut your mouth,” yet another person could be heard shouting. Some of the heckling, not surprisingly, continued even once he had begun.

Some of the interrupting was by what one might call professional hecklers. The person heckling in the photo on the right below (being confronted by security personnel who asked him to stop) has previously been spotted elsewhere with signs saying “leftists are traitors” (photo on the left below) and with one of his chief fans (in the middle).

But not all the disruption was done by people who now make a life out of challenging Bibi’s opponents at every turn. Some of the hecklers were family members of victims of terror or fallen soldiers. Their agony, obviously, never dissipates. That is the point of the country coming to a standstill on Yom Hazikaron.

The silence is about honoring the fallen, but also about acknowledging the unbearable and enduring pain of those who remain behind.

Yet if Israel matters, that agony cannot be allowed to excuse the behavior to which we were witness this year. If the sacrifice that their sons and daughters, fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers made is to mean anything at all, the society they bequeathed us has to survive. And to survive, it must avoid, at all costs, the tearing asunder of which we Israelis are witness across the Atlantic Ocean.

“Bennett, someone who formed a government with terror supporters is not welcome here,” said a sign held by a woman whose daughter was killed by terrorists. But—love him or not—in what way has Bennett formed a government with someone who condones terror?

The reference was most likely to Mansour Abbas, who heads the first Arab party to be part of a coalition and who has, for now, astonishingly been among those keeping the coalition from falling.

Mansour Abbas is not a Zionist. There’s no reason that any Israeli Arab would be a Zionist; after all, Zionism is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people. Yet, Abbas does represent that slice of Israeli Arab society that has decided to use its political power not to call for ending Israel’s being a Jewish state (which is futile, thankfully), but to improve its status inside the Israel that exists. He has specifically said that Israel will always be a Jewish state. Israeli Arabs like him are becoming involved in the apparatus of democracy, which among other things, means seeking power.

If Arabs are 20% of Israel’s population and an Israeli Arab with Mansour Abbas’ approach is not a legitimate coalition partner (whatever he might have said in the past), who is? Would the person holding up that sign say that Israeli Arabs should never be part of a coalition? That Israeli Arabs are by definition supporters of terror and therefore never legitimate political partners?

One does not need to be a savvy political theorist to know where that attitude leads. How many of us would want to live in such a country?

Even in heartbreak of mourning, there are things we can say—and things that we cannot. Those people who cannot tell the difference or who do not care are fissures in the foundation of everything we have built.

What transpired on Yom Hazikaron, though, was worrisome for reasons other than the implicit views that a small number of angry Jews harbor about Israeli Arabs. What was troubling, and what other bereaved families responded to in their critique of those who disrupted, was that a once sacred Israeli ceremony had now been defiled. Those of us who live in Israel and watch America from afar are witness to what happens when codes of civility and a sense of shared purpose begin to evaporate. As we watch the erosion of civil society in the country on which we once modeled ourselves, most of know that we do not want, and cannot afford, to become what is happening across the ocean.

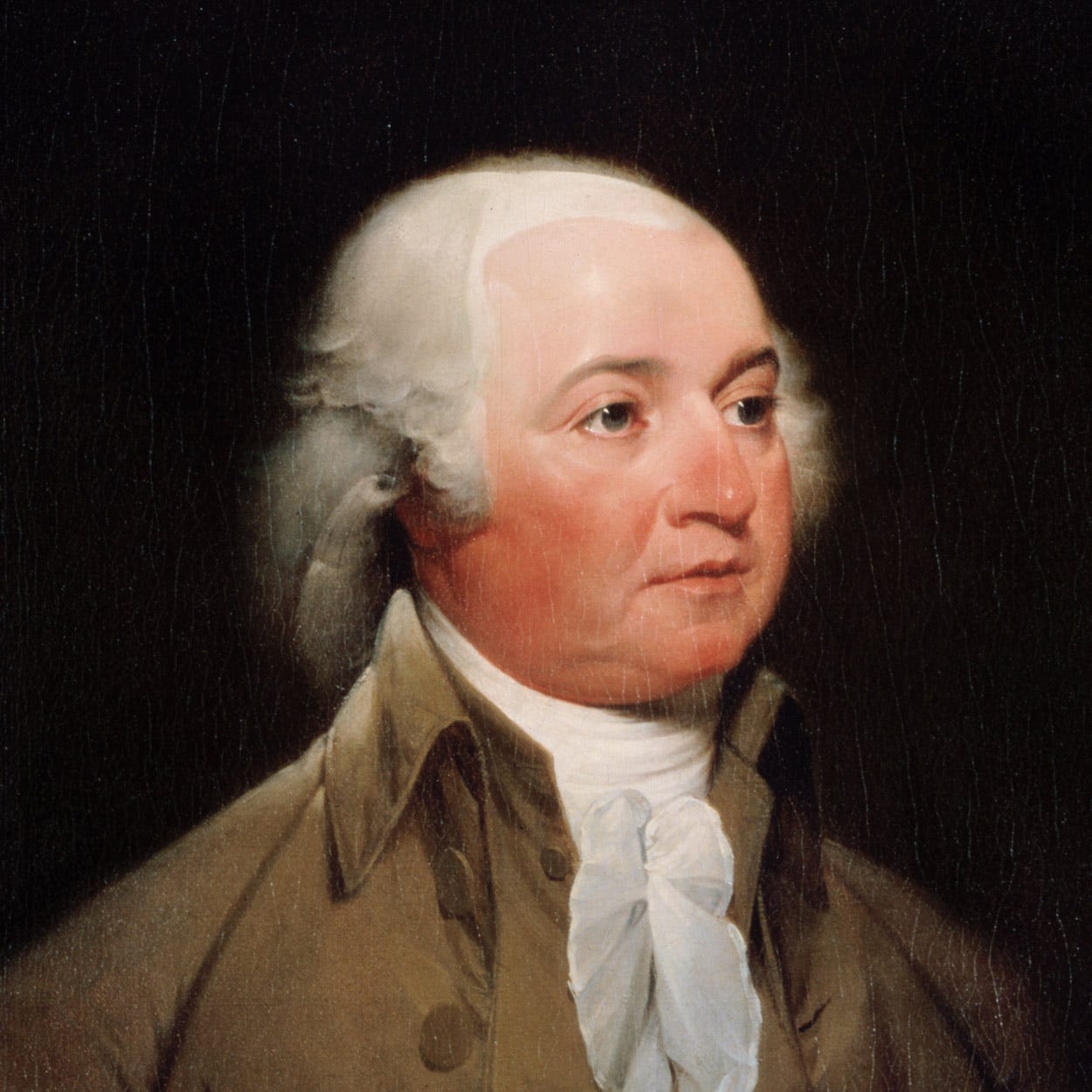

For that reason, we Israelis would do well to recall what John Adams said to the Massachusetts militia eleven years after the Constitution was ratified. He famously wrote that “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

But as David French insightfully notes, the sentences that preceded that quote were the genuine warning for our age:

Because We have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion. Avarice, Ambition, Revenge or Galantry, would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net.

I read David French’s column on “public virtue” with great admiration, and then thought of it once again when Yom Hazikaron was so sullied. French and Adams are right: Governments cannot preserve themselves when societies are no longer governed by a notion of public virtue. Governments cannot survive when societies do not see themselves as part of a larger whole, when they do not have a sense of shared purpose. And they cannot cultivate or express that same purpose without certain places, certain moments, that are sacred.

No religion worth its salt is devoid of ritual. Most well-functioning marriages have their (often unspoken) rituals. And in both religion and marriage, those rituals have the power that they have because participants understand that they must be sacred, that the community or the marriage cannot survive when they are defiled.

When a country comes to a complete standstill (see the YouTube above) to honor the fallen, no one—no matter how angry or heartbroken—has a right to rob society of the sanctity of a national moment. A society in which any type of behavior is either protected or tolerated is one that is headed to oblivion.

The fact that the outcry against the defilers was as muted as it was is no less worrisome than the defiling itself.

I’m still bemused each year by the attention that the IAF Independence Day flyover gets each year. All the news websites tell you when the planes will be over your city, at precisely what time which sort of plane will be in the sky (they added drones this year). Out and about on the roads, as the planes fly above, people don’t quite stop, but they do slow down and crane their necks out the window to watch.

Elsewhere, as below, crowds actually gather to watch.

It’s cute, but there are years that it also feels to me a bit provincial. Of course, I understand that on a deep level, Israeli air power is about the end of Jewish defenselessness, which is one of the prime purposes of the country. Still, at times, the enthrallment with airplanes strikes me as quaint, if not a bit odd (though I admit that I also get caught up in it).

This year, though, I felt differently. It’s naive, it’s provincial, it’s a bit cute, and it’s even a bit odd. But it was also the perfect antidote to the desecration of the day that had preceded it. Young and old, left and right, religious and secular, Haredi and not, yes, even Jews and Arabs, Israelis head to the streets, to their porches, to open parking lots and even to the beaches to watch the airplanes, to gaze at the machines that at the end of the day keep them safe, that have transformed the fundamental condition of the Jewish people.

I’ll take naive and provincial, if it restores some of that sense of purpose. I’ll take cute and even odd if it’s a balm for the horrific behavior of the day before. Because at least at that moment, people were willing to be in awe. At least in that moment, there was no being abashed about being proud. At least at that moment, there was a sense of unity.

But Yom Hazikaron—and the muted public outcry after it—should be a dire warning. If we can summon unity only when there are planes overhead, we risk getting to the day that there will be nothing for them to protect.

One of the most interesting new publications to hit the Jewish world is Sapir, which bills itself (quite rightly) as a “Journal of Jewish Conversation.” It’s excellent.

On its website, Sapir has this to say:

SAPIR is a journal exploring the future of the American Jewish community and its intersection with cultural, social, and political issues. It is published by Maimonides Fund with Bret Stephens serving as Editor-in-Chief and Felicia Herman as Managing Editor.

Sapir’s latest issue is about Zionism. It’s chock full of superb pieces that will keep you reading (and thinking) for quite some time. I’d point to a few that I thought were particularly stimulating, but that wouldn’t be fair—so many of them are that good. But you should definitely check out Sapir’s latest issue on Zionism.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Extremely powerful article. The heckling during the Yom HaAtzmut ceremony was disgusting, reminiscent of the intolerance now so prevalent in the US and other western democracies.

This powerful, nuanced essay about the sacredness of civil rituals is not to be missed. Sadly, and correctly, Gordis' negative example of civil rituals defiled is recent events in the United States. This is why I profoundly wish that AIPAC did not decide to support Jim Jordan and dozens of others aiming to undermine American democratic elections.