"I do not know what will be the end of you."

Our run-in with the KGB in Kyiv years ago is a constant reminder of how Israel has changed everything.

It was forty years ago this winter that my (then newly minted) wife and I got caught by the KGB in Kyiv.

We were among the many American Jewish students (and others) who were sent over the years by an Israeli government office located in the States that was hazily named the lishkah, or “Bureau.” The purpose of the lishkah was to get American Jews, most of us very young, to visit Soviet Jews, to try to return with information about them and their families so that they could be “invited” to Israel, to teach, to bring them books and other items they needed for Jewish life and perhaps most importantly, to try raise their morale.

In Moscow, things went fine. We were trailed all the time (except for the time that we went into a store so I could buy an Ushanka, one of those Russian fur hats, and wore it out of the store; the KGB agent didn’t realize that it was us leaving—but he quickly figured it out). We saw the people we were supposed to see, distributed what we’d brought and flew to Kyiv with no problem.

But professional spies we were not. On our first night in Kyiv, as we came back to the hotel after walking around town, we saw that the KGB guys were parking themselves in the hotel lobby so that they’d see us if we left. The whole vibe was more aggressive, so we figured Kyiv might be tougher than Moscow. We wrote each other notes in our room and devised a plan. We slept in our clothes, put the alarm under a pillow, and very early in the morning, got up, didn’t say a word and slipped out of our room, down to the lobby where the KGB agents were fast asleep (drunk, perhaps?) and out the door onto the street. Then we started out for the first of the apartments we were supposed to visit.

When we got there, though, no one was home. (Or at least no one answered the door.) In what turns out to have been a highly amateurish move, we left a note slipped under the door—but we didn’t manage to slide it all the way in. A little corner of the paper still stuck out. “We are friends, we will return,” we’d written. After going to a few other apartments during the day, we did just that and headed back to the first apartment. Turns out, though, the Russians (who were most displeased with our having given them the early-morning-slip), figured out who were some of the Jewish families we were most likely to try to visit—and the Russians could also read English.

We entered to the stairwell of the apartment, just as dark and dank as it had been that morning. Out of the shadows there suddenly appeared a gigantic KGB agent who blocked our way. “Where are you going?” he wanted to know. That was perhaps the very definition of a rhetorical question. What we stammered in response I no longer recall.

Elisheva and I both remember, to this day, his enormous hands, which he kept smacking together as he spoke to us. The knuckles were painted green. Some sort of Russian iodine? If so, how did the guy’s hands get so bruised? We never found out.

“You will stop what you are doing in Kyiv, or I do not know what will be the end of you. Do you understand?” We did, indeed, understand. Then, for entirely unnecessary added emphasis, he repeated. “I do not know what will be the end of you.”

If he was trying to scare us, he was quite successful. He made it clear that nothing would have delighted him more than beating the crap out of both of us. We suspected that he wouldn’t do it (he didn’t—there were limits with American citizens, I guess), but we were petrified.

So for the day or two that we still had in Kyiv, we were obedient tourists. We went to the catacombs (photo at the top of this post), a museum or two, and spent some time checking out the glorious monument in memory of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Ukrainian Cossack leader who was responsible for the slaughter of tens of thousands of Jews. (In the midst of all the horror and even as our hearts break for the Ukrainians, Jewish historical truth mandates that we recall that during the Holocaust, no one—not even the Poles—delighted in slaughtering the Jews more than the Ukrainians.)

We went on to Odessa, where things went better, and then flew back home to New York. In the years since, we’ve been back to Moscow and to Odessa a few times, but never to Kyiv.

I’m not sure why. True, unlike Moscow and Odessa, work has never brought me there, but maybe on some subliminal level it’s because Kyiv, for both of us, still evokes terror. Yet we knew even then, petrified though we were, that the fear and vulnerability that we felt paled to utter insignificance relative to what those Jews whom we were trying to visit felt. Every day. Every month. Every year, for as long as they were trapped. After all, we knew even as we were terrified that we were American citizens. The next few days might be more pleasant or less, but we would get to leave. They wouldn’t. There was a place for them to go, but no way they could get out.

It was a part of the world where being Jewish meant being terrified. Kyiv is still terrifying, and horrifyingly tragic. The Jews there are terrified, too—but this time, it’s not because they are Jews. If anything, being Jews makes things much better.

And what has made the difference is Israel’s standing in the world.

Israelis are watching a war in which a gigantic country tries to swallow up or destroy a smaller one, while the world, even as it sends aid, won’t stop it. We watch Ukraine and know it could one day be us. We see the photographs of burnt-out cities and know that if Iran gets its way or Hezbollah gets its signal, those could be Tel Aviv.

Still, though, the overwhelming sentiment here is not helplessness or worry. The sentiment here is that this time, because of this place the Jews are in a different place.

When Shabbat ended, we anxiously turned on our phones to see what was new. The lead story was that Naftali Bennett, Israel’s first observant PM, had flown on Shabbat to meet with Putin. The meeting was still going on, the news sites said. Later, Bennett went on to Berlin where he met with the German Chancellor. Since then, the pundits have been analyzing what really got discussed (most of the writers assume it was Iran, among other things, since many Israelis are hoping that a silver lining of the present horror is that the Iran deal might be delayed; plus of course the war and perhaps most importantly, an exit corridor for the Jews who want to leave and come to Israel). The pundits are also all opining on whether the political risk Bennett took by making the trip was worth it, what will be the fallout if Putin agrees to nothing (Bennett can ask Macron about that).

I’m not too worried about Bennett. In fact, he seems to me a metaphor for this state as a whole. He won only six seats out of 120 in Israel’s most recent national elections, but ended up Prime Minister and is now one of the higher profile personalities on the international stage. And this little state, the size of New Jersey with population just slightly larger than that of New York City is, like Bennett, punching way above its weight.

Why? Because behind all the chatter of the daily news, this is a country animated by the knowledge that it was created for a purpose.

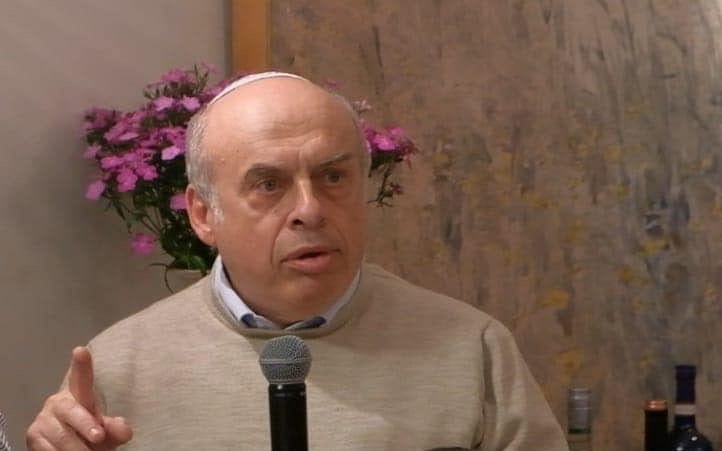

No one is poised to reflect more poignantly on what Jewish statehood has meant for the Jewish people, particularly with what is unfolding in Europe, than Natan Sharansky. A few days ago, Sharansky spoke at a sheva berakhot (a celebration during the first week after a wedding) for a couple—the groom’s parents had been killed in a terrorist attack when he was 7 years old. Here’s what Sharansky had to say:

When I was growing up in Ukraine, in Donetsk, there were many nations and nationalities. There were those with identity papers that read “Russian,” “Ukrainian,” “Georgian,” or “Kozak.” This was not so important since there was not much difference between them. The single designation that stood out was “Jew.” If that was written as your identity, it was as if you had a disease.

We knew nothing about Judaism. There was nothing significant about our Jewish identity other than the anti-Semitism, hatred, and discriminatory treatment we experienced because of it. When it came to a university application, for example, no one tried to change his designation from “Russian” to “Ukrainian” because it did not matter. However, if you could change your designation of “Jew,” it substantially improved your chances of university admission.

This week, I was reminded of those days when I saw thousands of people standing at the borders of Ukraine trying to escape. They are standing there day and night and there is only one word that can help them get out: “Jew.” If you are a Jew, there are Jews outside who care about and are waiting for you. There is someone on the other side of the border who is searching for you. Your chances of leaving are excellent.

The world has changed. When I was a child, “Jew” was an unfortunate designation. No one envied us. But today on the Ukrainian border, identifying as a Jew is a most fortunate circumstance. It describes those who have a place to go, where their family, an entire nation, is waiting for them on the other side.

In the last few years, I’ve been stunned, when I speak to American college students, that most of them have no idea who Natan Sharansky is. They’ve literally never heard of him. That’s heartbreaking on many levels, among them the fact that in addition to everything else, Sharansky is probably the Jewish people’s greatest living hero. Beyond that, though, having no idea of what Sharansky—and many others, for generations before him—endured simply because he was a Jew in the wrong place makes it impossible to understand why this country exists.

While Ukraine is on your mind, here’s a picture of Ukrainian Jews to remind us all what life was like when the non-Jews came to town (in this case, Khodorkov):

Without a knowledge of the history of European Jews, Israel makes no sense. Without reading Hess or Pinsker or Jabotinsky, Israel makes no sense. If you know nothing about how Israel got American Jews to do their bit to try to save Soviet Jewry, Israel makes no sense.

And too many of the young people whose loyalty we have lost know none of that. But it’s not their fault. We just didn’t teach them.

And that is why we face the challenge we do with that younger generation. Take away purpose, and all you’ve got is politics. Take away Hebrew and all you’ve got is international politics. Which means the conflict. Yet, as my friend and neighbor in Jerusalem, Rabbi Richard Block, one of the great Reform rabbis of our generation, likes to say, “Israel is much more than the sum of its conflicts.” Much more, in fact.

Israel was not created to be in conflict. It was created to change the existential condition of the Jewish people. It was meant to be a place where the Jews’ language could be revived, so that Jewish culture could flourish as it can only in its native tongue. It was meant to be a place where Jews would live without the pressure to assimilate, without the fear of anti-Semitism. It was created so there would be no frightened, trapped Jews waiting for visitors from a foreign country to buoy their spirits. It was created to fashion a way of life in which Jewish content would hover in the ether, from the national calendar to the national public school curriculum to the army to the press. And it was meant to be a place that would end the day of Jews being pawns on the international chessboard, and make them players once again.

Eighty years ago, no Jewish leader flew to Berlin to advocate on behalf of Jews, or on behalf of anything else, for that matter. Forty years ago, no Israeli leader could fly to the Kremlin to advocate on behalf of Jews in a war-torn Europe. Seventy-five years ago, Jewish orphans couldn’t get into this country—the British made sure of that.

Today, though, when he got back from Russia, Bennett was at the airport again, greeting several dozen Ukrainian Jewish orphans. Bennett (of course aware of the photo op) met some on the plane; one boy he picked up and carried down. (See also this clip tweeted by Israel’s Kan News Network; yes, the music is kitschy— it is what it is.)

What’s the purpose of this country? The obvious photo-op notwithstanding, that’s the purpose. It’s dignity for the Jewish people. Self-sufficiency for the Jewish people. Brighter horizons for the Jewish people. If today’s young Western Jews don’t get that, it’s because we failed to teach. And if there is any silver lining to the horror unfolding in Europe these days, it is that now we have another chance. To remind all those young people what Sharansky said— if you’re a Jew, you have a place to go. That’s not worth everything?

Those wounded Jews of Khodorkov above didn’t have a place to go. They just had to wait for it to happen all over again. And it did.

Is Israel mired in a dragging, depressing conflict? Yes. Does Israel conduct that conflict as some of us might like it to? No. Is Israel’s treatment of non-Orthodox Jews reprehensible? Yes. Is this society, like every other Western society, replete with challenges, problems and failures? Yes.

And are those issues what Israel is all about? No.

(Can you sum up the United States by discussing its wars?)

Watch Israel’s PM head to the Kremlin on Shabbat. Watch him return and take kids off the plane. Watch a nation gear up (and tear up, frankly) to welcome what may become tens of thousands of immigrants. And if you speak Hebrew, and keep your ear near the tracks, listen to the press and the news and the talk on the sidewalks and what you’ll hear is a sense of purpose being rekindled.

Here’s what we really ought to be asking: If the purpose of Israel was to change the existential condition of the Jews, has Israel succeeded?

That, too, is an entirely rhetorical question. In fact, it’s not a question at all.

Escape from Afghanistan—The role individual Israelis played in saving Afghan lives; A conversation with Danna Harman

In this week, when our focus is once again on rescue, and particular the Jewish world’s gearing up for a massive rescue, we share a conversation with Danna Harman, an Israeli journalist who, along with a few other Israelis, did extraordinary things to save Afghans who were left behind after the sudden American exit.

Hers is a story of determination, grit, collaboration and true Israeli imaginativeness—all for the purpose of saving lives.

Danna Harman has lived in and reported stories from around the globe including Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Myanmar and the jungles of Papua New Guinea. She began her journalism career over 25 years ago with the Associated Press in Jerusalem and later became The Jerusalem Post’s diplomatic correspondent. Today, she is a staffer for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz and her freelance work appears in various other outlets and magazines such as The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and Elle and Porter. She is a frequent contributor to the podcast Israel Story.

Here’s a brief excerpt of our conversation. The full podcast, as always, will follow on Thursday, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.