Today we mark the Memorial Day for the Israeli Ethiopian community who perished in the Ethiopian exodus to Israel in the 1980s and 90s. We do so with a conversation with Dr. Marva Shalev Marom, on whom you can read more below.

Today’s focus on the Ethiopian community affords an opportunity to mention facts that deserve more attention than they’ve received. Though Ethiopian Jews represent a mere 1.5% of the Israeli population, since October 7th, at least 26 soldiers and police officers of Ethiopian descent, as well as three civilians, have been killed. That is much higher than the national rate.

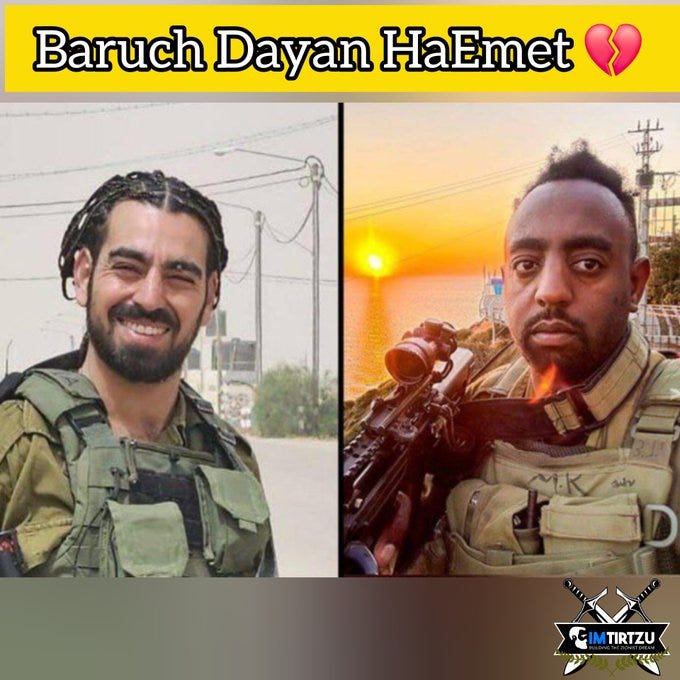

Tragically, images like this are not in the least bit uncommon these days. Thankfully, the issue of race no longer strikes anyone as interesting. These are young Israeli men. Period.

Yet the stories behind the photos can be heartbreaking. In this instance, Master Sgt. (Res.) Kalkidan Mehari (on the right) was killed in Gaza in April. At 18 years old, he came to Israel alone; his mother, who was not approved for Aliyah, remained in Ethiopia.

Still, there is great progress with the Ethiopian community, so today, on this holiday meant to mark the memories of those who perished on their way to Israel, our conversation with Dr. Marva Shalev Marom.

Dr. Marva Shalev Marom was born and raised in Jerusalem, and for more than a decade she has dedicated herself to music education programs in collaboration with Ethiopian Israeli youths in the Tel Aviv periphery. She is the Golinkin Chair of TALI Jewish Education at the Schechter Institute for Jewish studies. She obtained her PhD from Stanford University, based on a collaborative, community-engaged research about the Jewish education of Jews of Ethiopian descent in Israel and in Ethiopia.

Marva is the founder and director of the YAMA M.A. program in Educational Leadership at Schechter, which trains educators in creating innovative pedagogies for studying Judaism by creating rich encounters between Jewish sources and diverse Israeli society.

She received her MA in Mystical Scripture in Hebrew and Sanskrit from Tel Aviv University. Marva hopes to contribute to the revitalization of Israeli society post October 7th, by generating a wholesome, all-Israeli approach to Jewish education which overcomes political and religious ruptures within Israeli society.

Her paper, Eat, Pray, Wait: The Informal Jewish Education of Ethiopian Youth Awaiting Aliyah, is the winner of the Journal of Jewish Education’s Article of the Year Award for 2023.

The link at the top of this posting will take you to the full recording of our conversation; below you will find a transcript for those who prefer to read, available specially for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside

My conversation today with Marva Shalev Marom was actually delayed by the war. Marva and I knew each other many, many, many years ago, probably like 20 years ago, something like that, and then reconnected because a friend of mine mentioned that she had just joined the faculty at the Schechter Institute for Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, and we'll hear more about that. I reached out to her when I found about her research on Ethiopian Jews and how they are being prepared to come to Israel while they're still in Ethiopia. I looked at the things that she'd written, and it just struck me as really being fascinating. So, I reached out to Marva, and she graciously agreed to come and tell us about her research. And then, of course, the war came, and the world changed, and we were almost exclusively focused on the trauma and the tragedy that Israel found itself in.

Israel still finds itself in the middle of trauma, and Israel is still very much rooted in an unfolding horrific tragedy. But it's sad to say that the war is becoming the new normal. And it's sad to say that I don't know many people here who think this war is going to be over in a matter of weeks or a matter of months. This is going to go on for a while, unfortunately. And how it will end and how it will be shaped, we don't know.

But what we do know is that life in Israel has to go on. And people who are fighting the war are fighting the war not for the sake of the fight, but for the sake of the country that they're defending. And what we've always tried to do here on Israel from the Inside is to give a fuller glimpse of a million different sides of that country, what we call the mosaic of Israeli life, music and literature and artists and writers and people who do extraordinary things in the public sector and nonprofits and everything.

Marva is actually exposing, through her research, an interesting part of Israeli life, how Israel prepares Ethiopians in Ethiopia to come to Israel, and what that says about how Israelis think people need to be prepared to be Israeli. It tells us a ton about Israel's image of Israeliness. And that, of course, raises a lot of questions about what's going on now because Israelis are now thinking all over again, well, what is this Israeliness that was attacked? What is this Israeliness that we fought over last year? What is this Israeliness that we're fighting in a very different, horrible way this year? So, we'll come to that. But we're going to go back to the beginning. I want to thank you, Marva, for taking the time. Tell us just a little bit about you and your academic career and how you got to working on Ethiopian children, and we'll go from there.

Wow, thank you so very much, Danny, for this invitation and for this introduction. We do know each other for many years, and I had the great privilege of really growing up on the knees of great Jewish educators. It's almost funny how close I fell to that tree. How did I get to doing research with children of Ethiopian descent in Ethiopia? This question draws back actually to many years before I started my academic career, when I was a teacher soldier in the army, in my obligatory army service. I was part of the education corps. And what I was basically mandated, what I had to do in terms of my service was to teach Hebrew to newly arrived immigrants. And until that very moment, I grew up in the very Ashkenazi, elitist, Jerusalemite vibe. I didn't really have friends of Ethiopian descent. I barely knew people of Ethiopian descent. But when I joined the army, and all of a sudden, I was stationed inside a community that recently made Aliyah from Ethiopia. I was supposed to teach Hebrew. Nobody wanted to learn Hebrew from me, but I did bring my guitar one day. And from that moment onwards, basically, my life changed. I had no idea that this encounter would change my life, but it did.

Eighteen years from there, I am now in the situation where the Ethiopian community is a great part of my life. What started as being a guitar teacher for those two years of army service continued with a music center that I founded and led in Bat Yam, Jaffa, working with children of Ethiopian descent. And for many years, actually, my academic career and my educational career were not really aligned, or they went to two separate directions. As an academic, I was really curious to learn about ancient Jewish scripture, and I studied, Sefer Yetzirah which is an enigmatic short Kabbalist text that we know almost nothing about. And I tried to understand what relationship that has to Sanskrit and ancient Indian phonetics. Everyone thought I was a New Age crazy, but then we realized that interpreters since the 10th century have been talking about India as a really important source for what we find in Sefer Yetzirah. So, I think that that opened my mind to what Judaism actually is.

And you did that degree where?

In Tel Aviv University. I did my Master's in religious studies there, and I was biking, actually, from Tel Aviv University to Bat Yam and back, and I could see these two different alleys of Jewishness, basically. One that is very textual and the other one that is alive and in touch with other sects in Israeli society. But there was a key moment where I realized that for my PhD, I would actually want to connect these two things. My grandfather taught me that in the Tzohar, they say that the sin of Adam was not that he ate from the tree of knowledge, but that he didn't eat from the tree of life. And so, you need to eat both of them together. And I thought, well, I will do a PhD in Jewish education, and I will see how do these great ancient truths translate into the messiness of everyday life.

And basically, up to that moment, I never spoke with my students of Ethiopian descent, my guitar students, about their Jewish identity, about their Ethiopian identity. Our encounter was a place to be inside music, which is like a very universal place to be and very personal. We didn't think about me being an Ashkenazi Jew coming from a different place in Israel. But as soon as I moved away to start studying at Stanford and started asking my students, my students of Ethiopian descent, basically, how did they learn to be Jewish in Israel, all of a sudden, a new world opened up to me. Basically, what I learned in Ethiopia or coming to Ethiopia was the longer was a continuation of that journey, which just began in that question. I must say, though, that I want to problematize the moment in which everything flipped, the moment in which we became from friends and people who do music together to the moment that I became a researcher that comes to investigate people of Ethiopian descent about their Jewish identity.

As soon as I started studying education and Jewish studies, I knew that I have a lot to learn from my students about what it means to be a Jew in Ethiopia and in Israel. I only heard echoes of the ancient tradition that brought them all the way to Israel and of their heroic journey through the desert. But I really had little knowledge about the circumstances of their lives.

And when I came back to the neighborhood that I used to play guitar in with IRB forms, no mother would sign anything. No parent that people I used to know for years, they didn't want me to interview their kids about their Jewish heritage. And I had no idea why. I thought, why? Don't you trust me? Don't you know me? And I remember crying to one of my students. And one day she told me, listen, my mother, she's not even your real problem. I will handle her signature, but your real problem is that you don't speak to the right people. You don't ask the right questions. And generally, you have no idea what you're talking about. And that moment was a key moment for me as a Ferenji researcher. Ferenji is a very important word in Amharic for a white person. I was an outsider, and I asked them a question that has absolutely fateful ramifications. If I ask them about their Jewish identity, I didn't know that the backstory of the fact that they wouldn't talk about it is that their families are actually separated on the basis of their Jewish identities, because one sister was deemed by the Israeli immigration authorities to be Jewish enough to make Aliyah, while her brother was not as Jewish as she was.

And I didn't know. It all seemed so absurd. I didn't know how to even start approaching this crazy situation. I was very, very lucky that throughout my PhD studies, I got the grant to travel to Ethiopia with my four research participants or participant researchers because they were part of this community-engaged process. And yes, so to go to Ethiopia and to realize the full extent of what it means to learn to be a Jew and to really make Aliyah to Israel from Ethiopia.

So, I know even less than you did. So, you go to Ethiopia, and you find that there's actually an entire system in place, right?

Yes.

That Israel has put into place to make these people, quote, unquote, get ready for being Israeli Jews. Tell us about it. Is it a school? Is it a camp? Is it a building? Is it a neighborhood? What are they learning? How much say do they have in what they're learning? Is this Israelis teaching and preaching to Ethiopians or the Israelis also learning about Ethiopian culture? What's happening in this place? How long are they there? What are the ages? Give us the whole story.

The whole story. Okay. I'll just begin with saying that, how did I find out that this this place actually exists? My question to the girls, to my research participants, was, how do you learn Jewishness in Israel? And one of their answers was, we already learned it in Ethiopia.

How old are these women that you're talking to?

When we did the research, they were between 13 and 17.

Okay, so they're really young.

Yes, they were teenagers. And one of them was like, but we didn't learn it in Israel. We actually learned it in Ethiopia. And I asked them, why? And then it turned out that all those community members in the neighborhood where I was working were actually part of the Ethiopian Jewish community that made Aliyah in recent decades, not in the '80s. And they were, according to the divisions, the formal divisions that are also very problematic, and that's why I hesitate to say them, there is a difference between beta Yisrael, which is one sect of the Jewish-Ethiopian community, and the Zera beta Yisrael, that are also mockingly named the Falash Mura. And for that reason, I prefer not to use that name.

And yet these two communities are separated on the basis of the conversion that happened in the late 19th century. There was an Anglican missionary in Ethiopia that swept Ethiopia and Jews who lived in villages that were mixed with Christians or Jews that wanted the authorities not to know that they were actually Jews. They were enlisted as Christians, or they tried to avoid that murder or that rape or whatever that mission brought to them.

In the end, that decision that they made in the late 19th century had fateful ramifications for coming to Israel, because while the Beta Yisrael made Aliyah throughout the '80s and the '90s, and we heard about the great exodus, the Ethiopian exodus…

And those are the ones who were not taken over by the Anglican?

Yes. They were the ones who would prefer to die than to be known as non-Jews or to eat with Christians even. When I think about myself in terms of the Beta Yisrael or Zera Beta Yisrael, if in Ethiopia there was a category for a secular Jew, so the Zera Beta Yisrael would have been that. They married among Jews, they ate kosher, but they didn't practice the entirety of the Jewish tradition. And so, the difference is, and it's also an intercommunal trauma, the differences between these communities, some community members told on others that they were Jews. There is still a lot of enmity among community members. And I'm sorry, it is a very long answer to your question. But basically, while the Beta Yisrael made Aliyah throughout the '80s and the '90s, the Zera Beta Yisrael…

Which means the seed of Beta Yisrael, literally translated.

Yes. Literally translated. The seed of Beta Yisrael, that after the mission, they returned to Judaism. They wanted to make Aliyah, too, but they were not in the lists. In the lists that the Israeli government used in order to determine who is actually a Jew and who isn't.

Just a little point, we will return to that later, but even the Beta Yisrael, when they came to Israel, they had to convert to receive Israeli citizenship. And that's a whole different story. But regarding the Zerah Beta Yisrael, the whole community center, the Tikvah Beit Knesset, all that formed because of the wait. Like And these community members, they packed all they had, and they walked hundreds of kilometers from their village to the Israeli embassy, only to discover that they weren't acknowledged as Jews, and that they will have to wait until they would be approved Aliyah.

Now, how long are they waiting?

So, in my paper, I wrote about one specific child, a teenager that I knew when he was 17, and his name is Mosenbet. Mosenbet in Amharic means waiting. His parents thought that his birth would bring an end to their decades long wait. And when we met him, he was already 17. So, it's since the 90s, basically, since 1990.

They had been waiting 30 years?

Yes. I mean, the problem here is the non-decisive category. And there's no clear state category for the Aliyah of these people. So that’s from the government's point of view sometimes some family members get to make Aliyah while others stay. And even in this war that we are living through now, there are soldiers whose mothers and brothers and sisters are still in Ethiopia, and they are sacrificing their lives now in the war.

I'll just point out to our listeners that we have unfortunately seen over the last five months, when you see the pictures in the morning of the soldiers who've been killed, there's been more than their share of Ethiopian faces.

Yes, absolutely.

It's been a very tragic side to that story as well.

It's a tragic side, and also, it's part of what this ancient community perceives as their Jewish destiny. One of the greatest religious leaders of this community said that like a drop returns to the ocean, we will return to Jerusalem. And indeed, for this community that from antiquity saw themselves as the descendants of the lost tribe of Dan, for them, the first exile, the destruction of the temple was also a destruction of the family. They did not partake in the family of the Jewish people until the late 19th century, basically…

All of rabbinic Judaism. Everything had formed, and they were completely out of the loop.

They kept the biblical law as if not moving, not budging from one little centimeter to any direction. A great example is the purity of blood, for example. There are two examples, actually. If you are Ethiopian and you want to get married, so you need to count seven generations back to see that there are no family relations between the bride and the groom. So, because the purity of blood is so important. And another example is the margam gojo, which is the menstruation huts that used to be in Ethiopia. It was in the autonomic space for women, actually, that when they were menstruating and after they gave birth to a boy, so for 40 days, and to a girl for 80 days, they would stay at the margam among women. And so that space actually gave them a lot of autonomy, a lot of freedom, and also a great religious duty. You know that in the tradition of Beta Yisrael, the women are mohelot. There isn't a mohel., Because if a child is born…

They're the circumcisers, just to translate.

Yes, the circumcisers, because the child is born in the margam, in the menstruation hut. So, the great grandmother of the village, she is the one to perform this holy act. And so, we sometimes wrongly think that the Ethiopian community in Israel has a different gender relationship, that the men are the sheer leaders of that community. But I think that skin deep, one of the things that I learned is how much leadership the women hold.

I want to return to your question. So, just imagine families uprooted, basically, with everything they have on their backs. They arrive from their village to the Israeli embassy in Gondar, and they are told to wait. For how long? A week, two, two months, three months. There is an expression we use in Israel. It's called Zman Ethiopia, Ethiopian time. That sometimes you schedule something with someone, and then they come a few hours later because it's not really the same time frame as we have in Israel or in the Western world. But actually, I think that the Ethiopian time or Zman Ethiopia is something that this community experienced in how the Israeli authorities treat them. Because while in Israel, there were all these debates, are the Falash Mura Zera Beta Yisrael in fact Jews? Could we treat their return to Judaism as authentic? Would we grant them citizenship? And at the same time, 25,000 olim from the post-Soviet Union received citizenship regardless of past conversions to Christianity and everything. There was a deep inequality there…

Is that deep inequality racially based, do you think?

I think so. Although the category of racism in Israel is something that has to be really defined well. But I think in terms of the human capital, the idea of the immigrants from the post-Soviet Union, they bring a Western worldview, they bring formal education. They bring things that a young country needs in order to continue developing. But I think that from the very beginning, unfortunately, the state of Israel did not see merit in the people who came from Ethiopia in how they are and in what they can contribute to society. I think in this tragic moment in history that we are now in, I think that the Ethiopian community could definitely teach us more about how to be a community and how to really survive as a whole. In terms of the Jewish education…

Well, let me just stay with that for one second. What would they teach us? What would we learn from them if we could? What does the Ethiopian tradition have to teach us at this fraught moment about how to survive?

So, I think the Ethiopian tradition is, first of all, based on respect, respect for elders, mostly. When you see your father or your grandfather, you kiss their knees. If they ask you to do something, to perform a duty for them, that respect comes first. I think that in terms of the honor that people get just for being who they are without proving anything, that deep respect is something that we all need. When Olim from Ethiopia first came to the army, they wouldn't look in the eyes of their commanders, and the commanders would send them to punishments and everything. But looking in the eye, it's disrespectful. And so, I think that that respect on the one hand, that's one thing we could definitely learn. Another thing is the wholeness of the community and the family. In anthropology, we talk about the Ethiopian family as one of the most resilient structures we know on Earth, because it's an organization that can receive more and more and more people without breaking. They are able to share. They are able to survive as a community. Think what makes a community with grandparents and little babies and toddlers walk through the desert for months and survive. I think that kind determination and being goal-centered and seeing the community as the whole. In many ways, we developed as Am HaSefer, the people of the book. But I think that in Ethiopia, since only the kes, only the great rabbi, the religious leader, could read, actually so, the way to observe the Torah was through the people and through the conduct among people. And I think you can see that among people of Ethiopian descent and in the families that they have many mixed families also, that they truly bring a way, a derech eretz, a way of being a community and being a society and having a unity that surpasses the differences between people. We have a lot to learn from them in that sense.

Yeah, you mentioned, by the way, just as these families marry, I mean, even among our friends, so many of our friends' kids have married Ethiopian people. So, their traditions are really coming in. You have these Jews that make Aliyah from the West Coast, the East Coast, from the Midwest. I mean, we're about as an Ashkenazi and whatever as you can be. And all of a sudden, your kid marries an Ethiopian man or woman, and you're exposed to a whole different way of constructing Jewish life, which is enriching. I mean, it's in no way diluting. It's much more enriching than we might have ever imagined.

Absolutely. And it's also a window to interesting varieties and interesting conflicts. I have a good friend who is of Ethiopian descent who married an Ashkenazi Israeli of a very kind of cool and nonconformist family. And when his mother died, they waited with the funeral, and they waited with the shiva. And her mother, she was like, what do you mean they're waiting? How could they wait? She was the first person to be there the next morning, and she couldn't understand how come these people are not performing the... when someone dies in the Ethiopian community, there's screaming, shouting, the entire community comes together. And all of a sudden, these Ashkenazim they want their privacy? How is that possible? So, these things definitely happen. Unfortunately, there are also like, ghettos of people of Ethiopian descent and of communities of Ethiopian descent that are formed also in terms of the education system. And that's how….

Inside Israel you’re talking about?

Inside Israel, definitely. Because as part of the conversion that Jews of Ethiopian descent have to go through in order to receive Israeli citizenship, they have to attend the chemed, the Jewish Orthodox, religious Orthodox part of the public education system in Israel. And that system prepares them or is part of their ongoing conversion in Israel. And that basically is what we see. We see the informal wing of that happening in Ethiopia. Because basically, while these people wait sometimes for months and years and sometimes for decades, children grow up and the community is formed in a little refugee camp that has been there temporarily for years.

And so, as children grow up, so we have Jewish-American organizations. We had for some time, the Jewish Agency was also partaking in what was happening in Gondar, but basically between private people and NGOs, people who cared about these community members, and they wanted them to have some sort of Jewish life and some a fun place to be while they were waiting. And at the same time, some rabbinate officials and people from Israel who knew the process they would have to undergo once they make Aliyah, they said, let's do one plus one. Let's be efficient. If they're already here waiting, let's teach them Hebrew. Let's teach them the prayers they would have to know to pass the conversion. Let's teach them some stuff that they will need to know at school and to learn at school. And therefore, all of a sudden, different organizations started to send volunteers. Most of the volunteers are of Jewish Orthodox descent.

Meaning it was more like Yeshiva crowds?

Yes, that they would go for the trip to Africa after the army. So, they would come to Gondar and to just do a Shabbat with these people and mix with the community and make arrangements for them. The time we got there, when we visited Ethiopia, it was 2018. It was over 25 years since those organizations started working there. So, by the time we arrived, there was already an organized summer camp that happened for about two months with Israeli volunteers that would come for three weeks and stay in a nearby hotel where they get kosher food, and they would just have a daily curriculum for the kids.

For how many kids?

Then it was 1,500.

From what age to what age?

2- 3 until 17, 18.

Okay. And what's their conception of Judaism? That these Israeli, mostly Ashkenazi, I'm guessing. Israeli mostly Ashkenazi, well-educated, certainly well-educated in Jewish stuff and probably fairly well-educated in Western things, too. Sophisticated technologically, laptops, the whole shebang, right? People like you and me. Just a little bit younger. They're coming. What do they think they need to teach Ethiopians about Judaism? If you were to stop or wake them up in the middle of the night and say, wait, before you think, what is important for Ethiopian kids who are getting ready to come to Israel to know about Israel, about Judaism, about whatever? What's the basic they have to get?

Well, that's such a great question. I think that in their approach embodies, I guess, the tragedy or the tragic relationship between the state of Israel and the Ethiopian community, unfortunately. On the one hand, these are really well-meaning people that they bring themselves there, a month of their lives to teach every morning, every day…

They're like shlichim. They're emissaries. Just like a Chabad shaliach would go to a far, flung place. They see themselves in the same way.

Yes. And their idea is that they are the representatives of the corrected form of Judaism, which is actually, it's a state law in Israel. The law of return has been re-articulated in 1970 to have a halakhic definition of a Jew, someone who is born to a Jewish mother and doesn't convert to a different religion and is solely Jewish. And even though in 1973, the Jews of Ethiopian descent were actually acknowledged as historically Jewish, it didn't make them halakhically Jewish. And therefore, the idea that a halakhic Jew is the authentic Jew, that's the idea that these kids, if I would wake them in the middle of the night, that's what they would tell me. They would say, listen, they need to go through the process that the entire people of Israel has gone through since the days of the Bible until now, that we have the halakha and we're cutting-edge Jewish. And these people, they still preserve biblical law…

So, they need to know everything that developed in Jewish religious tradition from after 586 BCE.

Yes.

The Mishnah, the Talmud, religious law, or kashrut, two sets of plates. Everything. Hanukkah, Purim. They have no idea about any of this.

Exactly.

And we're going to teach them.

We're going to teach them. And also, we are going to teach them things that they would need practically in order to pass the conversion. They're like all the tricks.

Sort of like a driver's education course.

Absolutely. These are the prayers you should teach your grandmother because your grandmother wouldn't recognize the hymn. She would recognize a different way to say it. So, teach it to your parents. And also, I think that's the heartbreaking thing. I had a great education there because I was there with my research participants who were all born and raised there, and they made Aliyah when they were five or six. And I remember when one of my participants, Mulu, she came back crying from prayer, and she said, I can't handle this. These kids think that Jerusalem is gold, that there are no wars and no Holocaust survivors scraping for food in the trash cans because that's what the volunteers tell them about Israel. And this kid asks me, can I have a notebook to learn Hebrew? A Hebrew notebook from Jerusalem? That is the one thing they want. And she said, my brother in Israel, he's the same age. You can't pay him to wake up to go to school. But these kids, they would write on the sidewalk if they don't have a notebook for Hebrew. So, these volunteers, they perpetuate these ideologies of Israel as a magical place, as the place where a Jewish dream come true, the land of milk and honey.

And this is what these kids get. And in many ways, I think a really core fact of Ethiopian Judaism is what they call Jerusalem. If you know people of Ethiopian descent, many of them are named Yerush. It's a girl's name, and Yerush means Jerusalem. And the passion and the longing for Jerusalem as the holiest place and their true place of belonging, that is what kept this Jewish community as a little isolated community of Jews in the diaspora with no relationship to any other Jewish community whatsoever. When Yosef Halevi came to the Ethiopian community in the 19th century, they were named falasha. Falasha is a degrading name they received in the 14th century. It means landless wanderer because they couldn't inherit land in Ethiopia. So, this Yosef Halevi came to them and he said, I am falasha like you. And they looked at him, stand. They didn't think that there were any other Jews in the world. Definitely not Ferenghi Jews. So that was the kind of difference.

And I think that for me, that difference was actually an invitation to learn a different form of Judaism, not to think about the halakhic form as the corrected form, but actually to see what could we learn from the way this community handles life together. I saw that through the eyes of my research participants. One thing that we learned that I noticed and that really taught me much is that as part of the Jewish education that the volunteers were trying to perform, they would have prayers, and they would also have sing-song activities. And there would be a window shade between where boys were and where girls were. And the kids hated it. They wanted to pray as one community. And one day I saw that they actually folded the shade so they could actually pray together. And I felt there a little conflict between two ways of being a Jewish community. Is this a community that stays united regardless of anything, or is this community that preserves separation among different kinds of people? And so definitely, those volunteers who came from Israel found a different way of being a Jewish community in Ethiopia.

Were they able to share that with others when they got back?

I'm not sure. I think some of them definitely. I am still in touch. When we arrived in Ethiopia, I had a great lesson to learn because as I told you, being a Ferenghi researcher, coming from the outside, even without me wanting to do so, I apply a lot of power. And so, my mission was, first of all, to try and equalize the power relations among us, even in the research process. And what happened a couple of days after I received the funding to take us all to Ethiopia was that I biked into the director of Jewish studies at Stanford, and I broke my legs straight through. I had a surgery. I couldn't walk. And when I called one of my research participants crying after I left the hospital a few days later, and I told her, “Alamnesh, I I'm sorry, but I had an accident. I can't walk. I don't know if we could make it to Gondar”. And then she said, oh, don't worry about it. Just focus on healing. We still have a couple of months. Just chill. It will be fine. And I'm like, what do you mean it will be fine? We need to get to Gondar. How could we get there when I can't even walk? She said, but we have experience in this. I'll carry you on my back. My father will be with us. He knows everyone, and we will take care of you. And for me, it was a great test of my courage because I came still with my crutches, and I didn't know the language, and I looked very different from anyone else. And they were my guides. They were my eyes and my ears, and they had the cameras, and they collected visual data. When I got there, I could really sit and observe.

Mostly, I was with the girls who came with me to do the research. But the volunteers, we did keep in touch with them for a while. I know that some of them are still very, very active in the community, in certain yeshivas, that they continue their learning process there. And many of the teenagers in Gondar, they became like Torah lovers, key Torah lovers. And I think that recently or last year, a person that competed for the Hidon HaTanakh, The National Bible Contest, won from Ethiopia, from Gondar, from that refugee camp.

And our listeners who are listening may have no idea how much you have to know to win that thing. It is insane.

My grandfather, who knew the Bible by heart, he didn't win. And to his last day, he was so bummed. But this kid did because his knowledge of the Bible was unbelievable. And in many ways, when you see that situation, it looks absurd because Jews have been waiting for Jerusalem, for Zion, for thousands of years. But now when Zion does exist and these people are still left out, and they study, and they pray, and they learn the Torah in order to become part of the Jewish people, and yet the state of Israel puts a gate in front of them and a gatekeeper that says, you have to change in terms of the Jew that you are in order to become part. It's almost absurd. But when we think about Judaism as something that developed and through revolutions, the rabbinical revolution was a key part of it. So, we can also understand that Israel is trying to articulate its Jewish identity in many definite ways, in almost bureaucratic forms of who is a Jew and who is not a Jew. You can't have half a pregnancy. And yet what we're really talking about is what does it mean to be a Jew? What does Jewishness constitute in fact? And when we see the whole parade of what is happening in Israel and a lot before the war, in the 10 months leading up to the war, we were thinking about what Jewishness means in Israel.

And what Israeliness means.

Yes. What Israeli means in terms of Jewishness also.

Right. And who's the real Jew, and how many different options ought there be. And those are the battles that we're still fighting.

Absolutely.

We're seeing, if anything, maybe it's an interesting way of turning the topic a little bit and then beginning to wrap up. One of the things that you and I are both seeing in the paper all the time, in the paper, on the radio, on TV, it's all over. These guys, mostly guys, some women, but mostly guys who are in a tank for 100 days, for 120 days, for 140 days. And there's one religious guy from the settlements, and there's one secular guy from Tel Aviv, and there's an Ethiopian guy, and there's a gay guy. And they're all a tank. And their fates are sealed together. What happens to one is going to happen to all. And they're all coming out of Gaza because Gaza has been largely demobilized, at least at this moment. And they're saying, we cannot go back to what we had between January and September of 2023. That's done. That's passed.

Do you have a sense in any way that the horror of what is unfolding now might soften Israeli's certainty about what Israeliness should be or what Jewishness should be and might create a more receptive world or more receptivity to hearing from the Ethiopian community, which still does remember some of its ancient traditions, say, well, you know what? We're all looking together in the dark. We're all holding candles in the dark, and half our candles are blowing out because this is a terrible time. Here is another way of construing what the Jewish world is. You think there's going to be more openness to that now?

I certainly hope so. I think that this is a huge opportunity. This unbelievable tragedy really brings us back to the core of what does it mean to be a Jew in terms of our humanness and also to the very basis of our Israeliness. I think that what happened in the months leading to the war was that secular Jews were becoming more and more and more secular. They were beginning to feel, not beginning, but they were feeling a lot of alienation towards Jewish sources. And what it means to be a Jew was embodied in the Haredi that doesn't go to the army, and they're like, we hate this. This is not who we are. Then comes October 7th, and people just are fully, wholly recruited to do ezra aditit and ezer mizion, and to bring food to people. And they realized that there was something Jewish about them even before they arrived to the texts, even before they arrived to what they believe or their faith in the very essence of who we are as a community.

And so, there are two phases to this. I think that the first one is that we really need as a society, and we are doing it now, as a society, we need to get reorganized on what being a Jew is. In Israel, it's the only place in the world that being a Jew is really a bureaucratic category that has to be defined in rubrics in a way that an administrative system could make sense. It's an immigration office. It has to have clear categories. But those who lose mostly from that clarity of categories are not only the Ethiopian Jews that fall between the chairs, but Jewishness itself that survived because of its diversity. And I think that as American Jews and Jews across the world see what happens in Israel and saw what happened in the months leading to the war, I think we all perceived a growing distance between Israel's redefinition of what it means to be a Jew, whether in the settlements or Harediness or in the rabbinate or anything, and the varieties of Jewish life across the world. If there is one thing that we all learned from this tragedy is how united we are across time and space, and also some humility that the Israeli reconfiguration of what it means to be a Jew, and even the new Jew that goes to war and fights, those things cannot be conflicted or totally separated from what made us Jews in the diaspora all along. And the fact that we are now in a joint struggle, it's not that Israel is the Jewish dream come true and the diaspora is just a place to wait. But in fact, we are a worldwide community that has the privilege of having a very multi-layer definition of Jewishness and Israeliness.

So, I hope that the Ethiopian community could contribute, first of all, through the people that are the most amazing people in in Israel, truly. It's such a wonderful community. But also, in terms of the ways of life, how to live modestly with respect and only with the essentials. These communities, they lived in the village for so many years with almost nothing to eat, and they would sustain entire communities with so many children and so many elders, and they would live a good life. So, I think that now, when we need in a way to start from scratch, I cannot think of a better paradigm than that of the tradition of Beta Yisrael to start us off with.

I also think that in terms of the differences or in terms of who is an Israeli, one of the most painful moments in my research was talking with my student, Warkitu, and she told me, I was 10 when I got my first A+ in math, and I was the only one in class. But the teacher was mad at us. How come she got it right and you Israelis didn't? She said, I was sure I Israeli. That's a very, very painful story because Warkitu made Aliyah to Israel like many others, all of us.

But they got called Israelis, and she didn't.

And she didn't. And why is that? And what does it mean to be the only East African Jewish diaspora to receive Israeli citizenship? They're definitely distinguishable by the color of their skin, but also by the variety of the Jewish tradition that they have. And so, I think that the greater lesson that we have to learn from them is also in terms of the Jewish ethnicity, how wide it actually is, and also in terms of the variety of the religious and civil preference and tradition to be Jews. We could totally redefine these things in touch with this tradition.

And open us up and make us richer and more accepting and more embracing and less sure of ourselves. We'll just end by saying the story that you told about this young woman who the teacher said, how come she got it and the Israelis didn't get it when she had thought of herself as Israeli. I don't know how old you were when the Dolphinarium attack took place. I forget. It was like 2000, 2001, something like that. I forget exactly when it was. But you were obviously much, much younger. I was well into adulthood at that point. And I remember the horrible, the scenes and the dead bodies. And it was on a Friday, if I'm not mistaken. And it was a terrorist who blew up a party place where people went to dance and whatever. And a ton of the kids who were killed were Russian kids. And I will never forget, as long as I live watching the news and seeing a young mother, late 30s, sobbing into the TV camera and saying to the reporter, “Now are you going to think we're Israelis? Now that our kids are here under the body bags, is that Israeli enough for you?” And it's the same comment with the teacher. We have no sense of how often people communicate you're not really Israeli.

And you know what maybe we'll end with this because he's a person who is important in both of our lives. Professor Seymour Fox, of blessed memory. Your dad and I both work very closely with him for many years. Your dad much longer than I did. But Seymour Fox is a very important person for me also. And an extraordinary person. And he told me once that there was somebody when he was working at Hebrew University in the School of Education, and he'd been here forever already. He'd been here for 20 years or 30 years, whatever it had been. He came in '67, I still remember. And his kids had all gone to the army and this and that. And one of the fellow faculty people said to him, well, we'll get you, and then we'll get some Israelis. And he said, well, how long do I have to be here? And how many of my kids have to go to the army for you to think of as Israeli? So, it's Seymour Fox, the American. It's the mother at the Dolphinarium. It's your protege who's in school and getting an A+ but she's not really Israeli. We have a lot of work to do here. And a lot of people are saying, maybe we should call this war the Second War of Independence because we have to build everything all over. There are reasons, yes, there's reasons, no, but we have so much to build.

Absolutely. And I think that the point that you raise now is truly the key. And I remember Seymour Fox as a toddler. I remember playing on the carpet at his place when we would watch the fireworks on Yom Haatzmaut, on Independence Day. It really is a privilege to have learned from this person, and even as a very, very young child. But I think that what you just said, it is basically, Israeliness used to be about exclusivity. I am Israeli, but you are not still. About exclusivity and sacrifice. How much do you have to give in order to become this? And I think that now we are learning that Israeliness, it's not about being exclusive. Haredis are exclusive, hilonis [secular] are exclusive. The datis [religious] are also exclusive, all these different groups. But being Israeli is about inclusivity. Those four people in the tank that they could agree on nothing, and yet they are still in the tank together and their lives are intertwined, and our lives are intertwined. I think we are now at the venture point of seeing inclusivity as the new pathway to Israeliness rather than the exclusivity.

That would render a very, very different Israel.

Hopefully.

Which you and I both hope and pray for. It's really great to have a chance to catch up with you after all this time. I hope that we will not wait another 20 years to do it again. But that the next time we get together, we'll be able to say that the worst of these days is behind us, that we are in the process of rebuilding, and we're rebuilding something much more including, and a new phase of Israeli life will have begun. It's really a delight to learn from you. Thank you so much.

Thank you, Danny.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our Threads feed is danielgordis. We’ll start to use it more shortly.

"Inclusivity, not exclusivity, is the new pathway to genuine Israeliness"