Might a gold medal not be his only legacy?

Artem Dolgopyat won Israel a Gold Medal, and in the process rekindled a long-simmering Israeli debate about what it means to be a Jew

Lev Paschov certainly never imagined that he would be buried twice.

An Israeli soldier who had immigrated to Israel from the former Soviet Union through the Law of Return (which allows anyone who had at least one Jewish grandparent to immigrate to Israel), Paschov was killed while on active duty in southern Lebanon in 1993. Because Paschov’s mother was not Jewish, he was, according to halakhah (Jewish religious law), not Jewish. The Israeli army’s rabbi therefore insisted that Paschov be buried outside the official military cemetery, which was consecrated exclusively for Jewish burial.

After a public outcry, Paschov’s corpse was exhumed, and he was buried a second time—this time, inside the Jewish military cemetery, though at its edge.

While most Israelis understand that traditional Jewish law defines a Jew as someone who either is born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism before a valid religious court, many were outraged that a man who had died defending the Jewish State and his fellow citizens could be denied the dignity of burial in a Jewish cemetery and a military cemetery.1

That was almost thirty years ago, and Paschov’s name has been mostly forgotten. But the issue that his death raised almost three decades ago has come roaring back in Israel, this time, thankfully, not as a result of a battlefield casualty, but as a result of the best Olympics Israel has ever had.

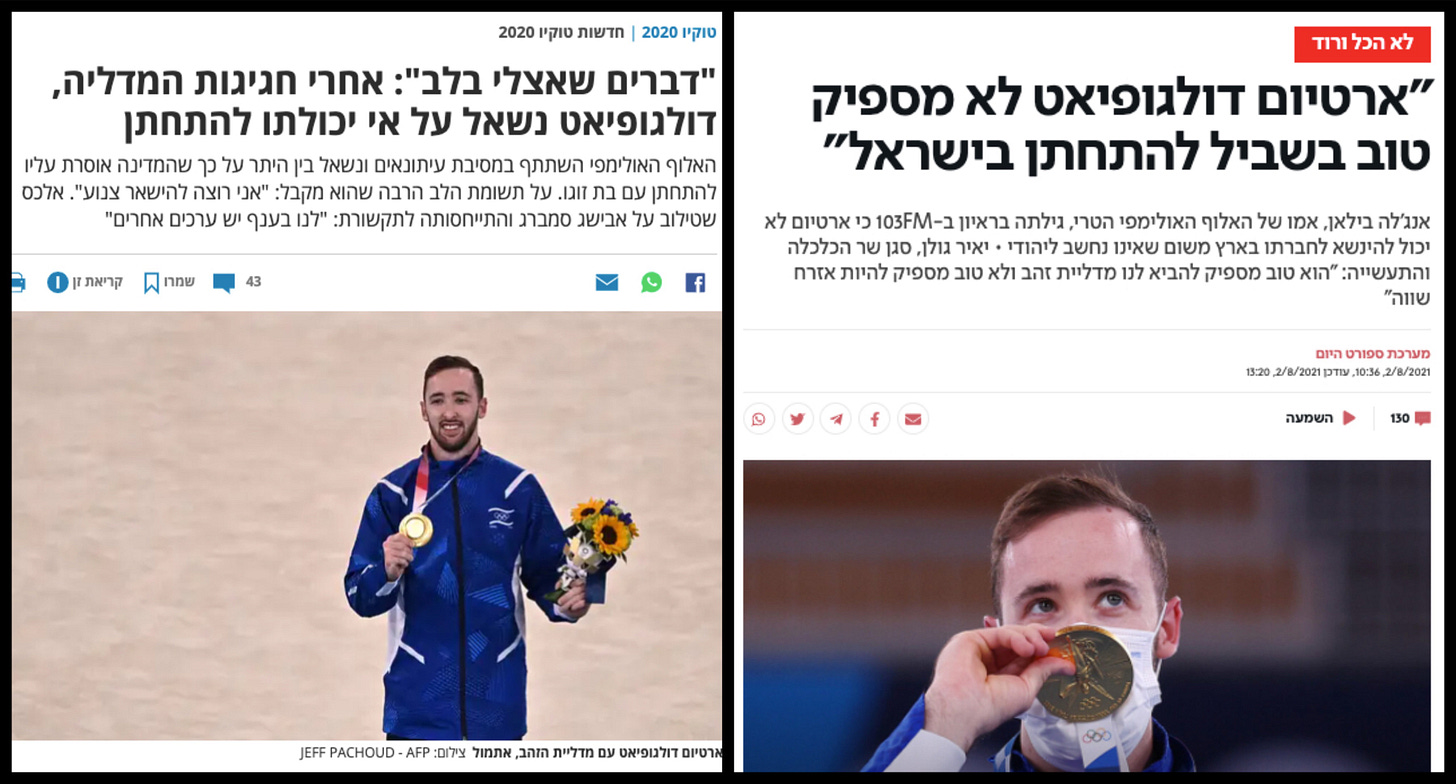

Israel won four medals in the Tokyo games, more than ever before. The first gold, in gymnastics, went to Artem Dolgopyat, of whom most of us had never heard until he won. But almost as soon as Dolgopyat, who said that he had competed “on behalf of the entire Jewish people,” climbed to the podium, bowed his head to accept the medal and stood at attention as Hatikvah was played (only the second time in Olympic history), controversy swarmed. Not about him, but about how the country was treating him. Dolgopyat, his mother pointed out, is not technically Jewish, so the country will not allow him to marry (there is no civil marriage in Israel).

The Paschov storm erupted once again. Israeli papers were peppered with headlines such as (in Yisrael Hayom (Israel Today), below on the right)

“Artem Dolgopyat Isn’t Good Enough to Get Married in Israel.”

The irony was obvious and intentional: if he’s good enough to be the best in the world, how is it possible he’s not good enough for something as simple as marriage?

What’s at play here is the distinction between “status” and “identity.” Before the modern era, there was essentially 100% overlap between a person’s sense of herself or himself as a Jew (identity) and their religious standing (status) as a Jew. In the last century or two, though, things have gotten much more complicated. Boundaries of Jewish communities became much more fluid (people could have the status of being Jewish, without identifying as Jewish), or as in the case of many immigrants (some estimates claim that some 75% of the one million Jews from the FSU who came to Israel may fall into this category; other estimates put the number at about half that), feel Jewish because they identify as Israeli (and sometimes either die for the country or win it a gold medal), without having the religious status of being Jewish.

Paschov was disinterred and reinterred, but beyond that, nothing much changed. Dolgopyat’s story alone also isn’t likely to alter much, but there are shifting sands in Israel that are worth paying attention to, and his story may become part of a much different picture.

Much of the Orthodox rabbinate and essentially the entire ultra-Orthodox establishment remain dead-set opposed to any change in Israeli policy which grants the rabbinate the right to determine who is a Jew, who can convert, who can be married, who can be buried where and the like. They don’t love the fact that the Ministry of the Interior can grant someone status as a “Jew” for the sake of immigration based on the “one grandparent rule,” but they’ve accepted that as the cost of their monopoly on the religious side of things.

That “one grandparent rule,” by the way, is derived from the Nazis. At Nuremberg, in 1935, the Nazis declared that anyone with a single Jewish grandparent, even if they identified as Christian, would be viewed as Jewish. Which ultimately meant, of course, that they would be murdered.

The 1970 revision to Israel’s Law of Return (which had first been passed in 1950, making it one of Israel’s earliest major pieces of legislation), which added the “single-grandparent provision,” was an intentional rebuff of Nazi madness. “If they were Jewish enough for you to murder them,” the law essentially said, “they’re Jewish enough for us to give them a home.”

The fact that the Ministry of the Interior and the Rabbinate defined Jewishness differently was obvious, but Israel chose to live with the complexity. And that is what may be slowly changing.

In this stormy country, many a political tempest has emerged from this complicated and painful issue. Some of them have gotten a good deal of international attention. There was the sordid tale of Rabbi Haim Drukman’s opposing many conversions and then having been accused of forging conversions, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate’s decision not to recognize even Orthodox conversions performed in America. The list goes on.

But away from the international headlines, garnering virtually no attention in the English-language press, there have been, for years, Orthodox Israeli rabbis who have been advocating very different approaches.

Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nun, one of the leading rabbinic figures in the Religious Zionist movement, is one prime example. Though recognized more as an exemplary teacher of Bible than as an authority on Jewish law, Bin-Nun is a charismatic leader with a huge following in Israel, particularly among young people who see him as a critically important religious authority.

In a 2003 article in the now defunct but once very influential Eretz Acheret,2 Rabbi Bin-Nun made the familiar argument that the existing legal structure in Israel was thoroughly unprepared to deal with the hundreds of thousands of Russian immigrants who were halakhically non-Jewish. As long as conversions are handled on an individual basis with the classical standards traditionally employed in cases of conversion (i.e., that prospective converts had to be willing to become observant), he argued, the system could never even hope to keep up with the number of persons who desire to convert. The Jewish State will eventually absorb a significant number of non-Jews into its ranks, he said, and that would undermine the very purpose and nature of the Jewish State.

So, Rabbi Bin-Nun made an extraordinary proposal: Israel ought to institute centralized mass conversion to bring these people formally into the Jewish fold.

In advocating a mass conversion ceremony, Bin-Nun was being revolutionary in sidestepping the critical issue of the level of observance of the prospective convert. To Bin-Nun’s mind, though, the national needs of the Jewish people residing in their sovereign state require a radical approach to conversion. Mindful of how revolutionary was his posture, he concluded his article with “Courage, my colleagues, courage.”

Rabbi Bin-Nun is not the only Orthodox Israeli rabbi who has urged the establishment to get creative. Some years ago, Rabbi Yigal Ariel, rabbi of the northern settlement of Nov in the Golan Heights, contended3 that “those approaches and arguments that have not heretofore been the basis of law might now, in this urgent time, be a basis for lenient rulings….” Ariel acknowledged that that these Russian olim are mostly not observant and that there is little chance that they will become so. On the other hand, he noted, they are living as “Jews” in the Jewish State, and their lot is intertwined with the Jewish people. Like Bin-Nun, he argued that it is in the state’s interest to find a way to convert these people. “Conversion [of these immigrants is] not the problem of the immigrants but the interest of the rabbinate, which is charged with saving Israeli society from a ‘stumbling block’ [wherein “Jews” of non-halakhic status would marry Jews of unquestioned status in possible intermarriages].”

Arguing that conversion is more than a religious act, but can also be a national one, Rabbi Ariel contended that there is precedent for conversion based on “national” rather than “theological” commitments. While he admitted that “the Russian immigrants do not know very much about Judaism,” he also insisted that “there is no doubt that they wish to become integrated into the nation and its land.” Those who join the Jewish people, as these immigrants have done by virtue of their becoming Israelis, should be eligible for conversion to Judaism no matter what their level of observance.

Yoel Bin-Nun and Yigal Ariel, like a good number of others, are clearly ahead of the pack, far beyond the comfort zone of most Israeli (and Diaspora) Orthodox rabbis. But might this be the era in which matters begin to shift? It’s not as impossible as it might sound.

While Naftali Bennett is Israel’s first Orthodox Prime Minister, the Bennett/Lapid government has already found itself in an adversarial relationship with the ultra-Orthodox, who are not part of the coalition. The government is advocating the privatization of kashrut supervision (which is precisely how it works in America, of course), which has the Chief Rabbinate enraged. The Haredim have all sorts of colorful things to say about this Orthodox Prime Minister; they’ve said that Bennett is “an ‘evil’ and ‘wicked’ Reform Jew who will rot,” while MK Moshe Gafni called Bennett a “murderer” in the Knesset last week, and was forcibly removed from the plenum.

All of this fury at Bennett is a mask, though, for weakness that the Haredim have not felt in a long time. The status of their leadership in their own communities has been badly bruised by their horrendous handling of Covid in the early phases of the pandemic. They used their power to pressure the police to approve the Lag Ba’Omer ceremonies at Mount Meron, and in so doing, contributed to Israel’s worst peace-time disaster; their followers know that 45 people died because of the rabbis. And now, they’re out of the coalition, watching the Orthodox Prime Minister dismantle their power, the Minister of the Treasury threaten their budgets … and the future looks no brighter.

Would anyone have believed that it would be the Haredim who would be suggesting that it may be time for a separation of religion and state? That’s precisely what’s unfolding here.

Is it possible that Artem Dolgopyat’s legacy to Israel will be more than even his extraordinary accomplishments at the Tokyo Olympics? Could be, who knows?

Would anyone have imagined that it would be the election of the hard-liner Menachem Begin, the former leader of the military underground who was hunted by the British, called a “murderer” and a “fascist” by American Jews and “Begin, rhymes with Fagin” by TIME Magazine, who would secure Israel’s first peace treaty with an Arab neighbor?

Would anyone have imagined that it would be the “bulldozer” Ariel Sharon who would pull out of Gaza (which has obviously not played out well)?

Would anyone have imagined that it would be the Bibi-Trump bromance that would bring Israel normalization with the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, Morocco and more?

So, will it be Israel’s first Orthodox Prime Minister, spurred by the extraordinary accomplishments of an Israeli athlete, who will shake up the relationship between religion and state? Will it be Bennett who begins to heal some of Israel’s divides?

We’ll see. It’s far too early to know, but it’s not too early to hope.

And hope, of course, is the business this country is in.

Does Israel’s Declaration of Independence really open with a lie?

Many scholars and observers claim that it does. The opening words of the Declaration are now quite well-known.4

In the Land of Israel, the Jewish people was born. Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.

If the Book of Books (i.e., the Bible) is so important that it merits mention in the Declaration’s opening sentences, why make a claim that explicitly contradicts the Bible’s history of the Jewish people? After all, the Bible states quite clearly that the Jewish people was not born in the Land of Israel.

The first time that Abraham’s family is called a people, they are in Egypt: Pharaoh says, “Look, the people of the sons of Israel is more numerous and vaster than we. Come, let us be shrewd with them lest they multiply” (Exodus 1:8-10).

A few chapters later, it’s God who speaks: “I will take you out from under the burdens of Egypt and I will rescue you from their bondage…. And I will take you to Me as a people and I will be your God” (Exodus 6:6-7). Here, too, they’re in Egypt, not Israel.

Still later, God speaks again: “And as for you, you will become for Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). Towards the very end of the Torah, as the Israelites are encamped in the deserts of Moab on the eastern side of the Jordan river, it is Moses who speaks: “Be still and listen, Israel. This day you have become a people to the Lord your God” (Deut. 27:9).

So what was David Ben-Gurion doing? Why open the Declaration with a purposeful mischaracterization of what the Bible says?

But what if it wasn’t a lie? What if we’re misunderstanding the word kam that we usually translate as “born”? What if Ben-Gurion actually dropped a hint of how to understand kam in that very same paragraph?

What’s the hint? We’ll be sending out a very brief column later this week to subscribers showing what Ben-Gurion (never shy, never understated) was really up to, and how that hint speaks volumes about what he thought of the Diaspora and about how he thought that the Jewish state, which was then home to about 5% of the world’s Jews, was about to transform the Jewish people.

It's rather fortuitous that we interviewed Rabbi Aaron Leibowitz, who heads the organization Chuppot, even before Artem Dolgopyat won Israel's first gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics, sparking a renewed debate about Israel's rabbinate, immigrants from the FSU and rabbinate's refusal to allow many of them to get married.

“Chuppot” is part of “Hashgacha Pratit”, an organization that challenges the monopoly of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel through the provision of private religious services. The organization was established in Jerusalem in 2012 by Rabbi Aaron Leibowitz, and successfully led the struggle to open the kosher food market in Israel to competition. And now it's pushing for major change in the world of weddings and marriage in Israel.

Our full conversation with Rabbi Leibowitz will be posted later this week and will be available to subscribers to "Israel from the Inside." We're making this brief excerpt of our conversation available to everyone.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Some of the background material in this column comes from Pledges of Jewish Allegiance: Conversion, Law, and Policymaking in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Orthodox Responsa, the book that my teacher, colleague and friend, Professor David Ellenson, and I published with Stanford University Press in 2012.

Bin-Nun, Yoel. “We Should Perform Mass, Centralized Conversion.” (Hebrew.) Eretz Acheret 17 (Av–Elul 5763 [July–August 2003]): 68–69.

Ariel, Yigal. “Conversion of Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union.” (Hebrew.) Teḥumin 12 (1991): 81–97.

This translation is based on the Yale University Avalon Project, with emendations on my part.