The audio link above is to a brief excerpt of our conversation with Rabbi Seth Farber, a visionary, courageous Orthodox rabbi who has taken on the Chief Rabbinate in myriad ways. Listen to Rabbi Farber for a vision of what Judaism in the Jewish state could look like, about why the Chief Rabbis are not Zionists, and much more.

This week’s written column follows below.

On a wind-swept, mostly barren hilltop overlooking Beit Shemesh on one side and tree-covered hills on the other, we buried my mom a few weeks ago.

We buried her precisely where she’d wanted to be for the past seven years—next to our dad. As we filled in her grave, his stone right at our feet, I was suddenly reminded of the day—just over a decade ago—when my dad told me that my parents had bought plots there. My mother’s father was already buried there, so that was a factor; but that wasn’t what my dad mentioned to me that day. What he said was this:

None of us can possibly know where the next generations of this family will live. People will spread out, and eventually, it’s quite possible that no one will live where other members of the family are buried [New Jersey, Long Island] …. But here? Someone in the family will always be here. Future generations of this family will come to this land regularly, no matter where they live.

When the funeral ended and we got in the car to drive back to Jerusalem to begin shiva, I began thinking that we had to order a stone. Which reminded me of a phone conversation I’d had outside my office seven years ago, not with my dad, but with the guy who made my dad’s stone.

There were, he told me, two ways to go. You can go with a stone that looks solid but is actually made of thinner stones on top and on the sides, or with a single massive stone [in Israel, they cover the entire grave, see image above] that covers the whole thing.

“What’s the advantage of each?” I asked him.

“Well, the single massive stone is significantly more expensive, and since it can’t be lifted by people, you also have to pay for a crane, which is also pricey.”

“What do most people do?”

“Almost everyone does the thinner stone. It looks almost exactly the same; it will also last forever.”

“I’ll take the heavy one.”

After a pause: “Really? Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

When I got home from work, I told my wife what I’d decided. She looked puzzled, and asked me why I did that. “Because,” I said, “think about the Mount of Olives and how the Jordanians took headstones from the Jewish cemetery there and turned them into urinals. Think about other Jewish cemeteries around here which have been defiled over the centuries. To say nothing of Jewish cemeteries throughout Europe. When we lose or are attacked, the graves get destroyed. The stones are destroyed in the most revolting ways. I want a stone that none of them will be able to move.”

I could tell she thought that was nuts, but I was raw enough back then that she didn’t push back. That’s what we got, and that’s what’s there.

And that’s what we just bought for our mom, too.

That’s the nature of this place. My dad chose to buy burial plots in Israel not only because he and my mom lived here, but because it’s the only land that’s truly eternal for the Jewish people. And I chose a massive, unmovable stone because who knows? Maybe it’s not so eternal, or at least not uninterruptedly so.

The Jewish world is having a conversation that is a variation of sorts on the theme of “eternal or not eternal.” Did the State of Israel just democratically commit suicide? Are Israel’s decency and legitimacy disappearing in front of our eyes? Or is this a distasteful group of characters who will likely do some—but not inestimable—damage, and who in any event, will eventually be gone?

It depends on who you ask.

As I’ve made clear in the past few columns, I’m not in the doomsday crowd. That’s not to say that I’m happy. I’m utterly sickened, and will never forgive Netanyahu for what he has unleashed to save his own legal skin. Ben-Gvir and Avi Maoz appall me in numerous ways (I’m no Smotrich fan, either, but he’s a different, much less unglued breed), but for an array of reasons, I suspect that they’re going to accomplish very little of their agenda.

Why?

The Biden administration, through Ambassador Tom Nides, it is now widely said, has already passed on to the Netanyahu government a list of red lines that the American government will not abide Israel’s violating. It’s virtually certain that some of them have to do with the West Bank / Judea and Samaria. Caught between Smotrich’s ambitions and Biden’s warnings, whom is Netanyahu going to heed?

A former IDF Chief of Staff said today that any steps that Israel might take vis-à-vis the Palestinians would likely weaken America support for steps Israel needs to take against Iran. How likely is Bibi to ignore those warnings?

Avi Maoz says he’s going to cancel the Gay Pride Parade in Jerusalem (where, I guess, he thinks it’s more offensive than in other cities). Bibi said, as soon as Maoz said that, that the parade will be left untouched. Kind of too bad, in a way. If Bibi had let Maoz “cancel” the parade, there would have been one anyway, likely five times as large as those we’ve traditionally had.

Ben-Gvir may well use the Border Police, which he now controls, to impose some law and order in the Negev. It’s likely not to be innocuous. But before we scream, how about an alternative suggestion? Anyone have one? Because no government—left, center or right—has lifted a finger to protect the Jewish residents of the Negev from the Bedouin. Why did many of those voters move from decades of Likud support to Ben-Gvir? Because he heard them. On that front, some action might not look pretty, but it is also overdue.

Want to separate bark from bite? MK Amir Ohana, openly gay and religiously traditional, was just confirmed as Israel’s first openly gay Speaker of the Knesset. With his partner sitting in the gallery of the Knesset, Ohana put on a kippah due to the sanctity of the moment. Guess who voted FOR him? Yup, Avi Maoz. Why? Because it turns out that politics are not simple, there are lots of considerations in every step. If Maoz couldn’t even muster a negative vote in a case where his voting “no” wouldn’t have made a bit of difference, he evidently understands something about the terrain.

What will happen with the Supreme Court? Hard to know, and here there might be more change, but as those on the Left and almost everyone outside of Israel is “schreing gevalt” about possible reforms to the judicial system, many centrists in Israel are opposing the Likud’s proposed changes but are nonetheless acknowledging that the system needs reforming. No one who is elected is involved in choosing a Supreme Court justice. The sitting justices can veto anyone they don’t want. Israel doesn’t have a formal constitution (yes, it has Basic Laws, which we’ve discussed in several of our podcasts), but the Supreme Court is empowered to declare laws “unconstitutional.” How many of the nay-sayers have been following the longstanding critique of Aharon Barak’s judicial revolution decades ago?

In the midst of all the worry (which is legitimate), it is no less critical to note as well the resurgence of the center and a moderate religious leadership, too.

And Israel’s President Herzog was 100% right when he said, a few days ago, “No one has the privilege to act or talk as if ‘the country is doomed’ or to reach out for their passport … I know that for many, this period is challenging and not an easy one. But Israeli democracy is long-standing …”. If he thinks Israelis have no right to give up on Israel, imagine what he would say about those who don’t have to live under the government and are still giving up.

As Americans (national politicians, journalists, rabbis (more on them in a moment) and rank and file American Jews) are saying kaddish for Israel’s democracy, Israel’s centrists are hoping to use the present situation to make repairs without doing great damage.

Will it work? I don’t know.

But how many of those wearing sackcloth and ashes are even aware of those moves? How many of those declaring that the Israel they knew and (half-heartedly) loved are aware that this government has also inspired a wave of social, democratic and moral discourse and action in Israel?

To know that, you would have to speak the language in which the country conducts itself.

How many of the doomsday crowd saw this ad all over Facebook, about a gathering later this month at Heichal Shlomo (more or less the seat of the Chief Rabbinate in downtown Jerusalem) which reads “Zion will be redeemed in Justice: Religious, Traditional and Haredi Jews seek peace, equality and justice. A conference of the ‘faithful’-left.”

How much would you understand about America if you did not understand English, if all you were able to read was coverage of the US in some other language? How many of those rabbis whose eulogies for Israel or its democracy I’ve been reading of late are aware of the surge of democratic revitalization that seems to be bubbling up across Israel? If many Israelis were not long ago tuned out of all conversations about such matters, now, there’s a resurgence of interest. Everyone? Obviously not. Many more than you’d have any idea about from all the English press put together? Absolutely.

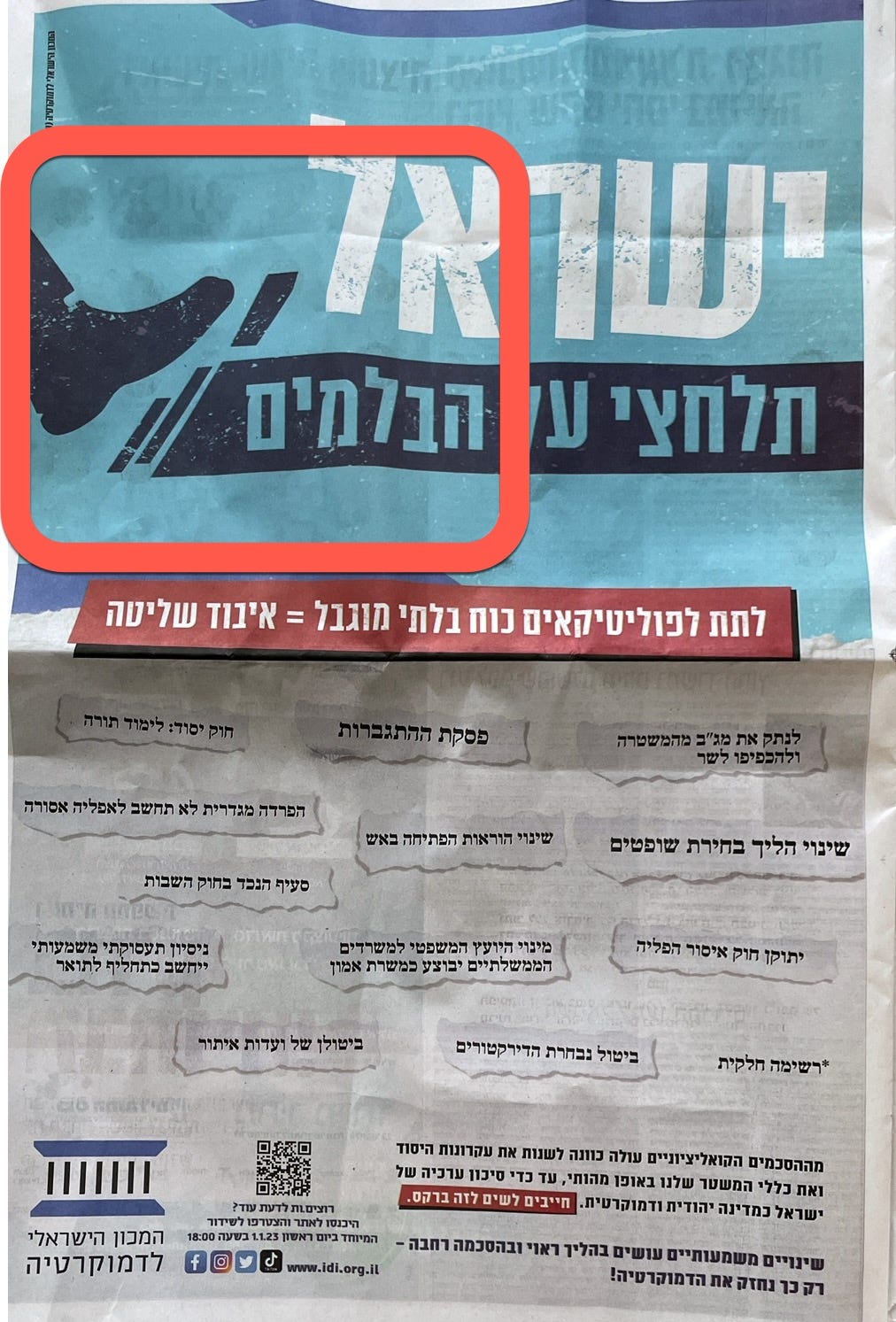

Not understanding Hebrew is hardly a crime. It is no intellectual mark of Cain, and obviously not a character flaw. But not understanding Hebrew well enough to read the serious press is (or at least ought to be) cause for some humility before one bemoans the end of Israel’s decency. If they don’t read the Hebrew press, those who say that Israel’s enlightened days are behind us have no way of knowing that in papers such as Makor Rishon, a religious paper with a definite right-of-center bent, there were ads this week from places like the Israel Democracy Institute warning the government not to overstep its bounds (“Step on the Brakes,” says the ad with a foot doing just that).

If they can’t read the Hebrew press (which most of them cannot), those rabbis bemoaning the end of an Israel they live to critique have no way of knowing that in that very same religious, right-of-center paper, there was a large ad that read “It’s time to draft the ultra-Orthodox.” Those behind the ad know that a step like that could bring down the government, and of course they know it could lead to violence on the streets … but it’s time, they say. That’s not exactly minor.

Well, you might say, anyone can buy ad space. Not entirely true, but that’s not for now. But if you didn’t read the Hebrew press this week, you wouldn’t know that in that very same Makor Rishon, on the front page, there was an opinion piece by (the unquestionably Orthodox) Rabbi Hayim Navon pointing out that the election was democratic, that these people were elected properly, and yet, at the same time, urging Smotrich, Ben-Gvir and Maoz to remember that now the campaigning has ended and it’s time to start governing—not only on behalf of those who voted for the government, but for those who voted against it, no less.

Those of the Noam party [DG-Avi Maoz’s anti-LGBT party] must stop poking their fingers into people’s eyes. Those from the Jewish Power party should honor their pledge and distance themselves from Arab-hatred. Those from the Religious Zionist party had better start being much more measured in their choice of words. The Likud has to remember that it also represents the silent majority. And the Haredim need to have an answer to the question: “What’s your vision for the future of Israel, given the large swathe of the population that you represent?”

No one could buy that space on the front page. And the column warning these parties to stop stoking the fires, to be responsible, to remember that they represent not just those who voted for them but those who didn’t, as well, came as we noted, yes—from a highly regarded Orthodox rabbi.

Does that mean we’re out of the danger zone? Of course not. There is a lot to worry about here. But does it mean that it’s all much more complicated than meets the (foreign, English-press-only consuming) eye? Definitely. The Israeli left is dead (it’s been gasping its last gasps for years), but the center is not. Quite the contrary. It’s quite possible that nothing will have done as much good for the center as this incoming government.

One last word about the seemingly incessant torrent of woe-is-us columns I’ve been reading by American rabbis and communal leaders of all sorts these past weeks, all declaring Israel-as-they-knew-it dead, bemoaning the fact that they can no longer support the Jewish state:

It’s only partially your fault that you cannot read the opinion or book review sections of Haaretz or Makor Rishon in Hebrew. It’s largely the fault of the schools that trained you, for they decided that being conversant in the language of the Jewish state was not a priority. They thought it was fine to ordain someone, to declare them fit to be a leader of the Jewish community, with no unmediated access to what is transpiring in the Jewish state, with no ability to hear or read what real Israelis are saying to and about each other.

But let’s be honest—it’s your fault, too. We all decide what we need to learn, what lacunae in our education we desperately need to fill. OK, your rabbinical schools failed you. But what about you? Why didn’t you make it a priority to be able to understand the Jewish state, to be able not just to understand some basics, but to follow this country’s voluminous discourse with genuine comprehension?

And as for that “I sadly cannot support the Jewish state anymore,” here’s my other question. When you were distraught about what was happening to the United States, why didn’t I hear you say “I can’t support America anymore”? Why in one case did you decide to get to work, to get politically engaged, to organize and to fight back, while in the other, you chose to wash your hands of a country because of a coalition government that didn’t even exist yet? What does it say about your worldview when the country that you did decide to wash your hands of is the only country on the planet whose express purpose is saving the Jewish people?

An election goes a way you don’t like and you announce that you’re done?

If that is what Jewish communities are willing to call leadership, then let’s be honest: we don’t even deserve to survive.

After we buried my father seven years ago, my wife and I bought plots in that same cemetery, just a few dozen meters away. Because my grandfather is there. Because now my parents are there. And because my father was right—this is the only place on the planet in which Jewish life is eternal. Someone from our clan will always be here.

There will be times that it will be better here, and times that it will be worse. But even in the bad times, this will still be the only place where it is certain that there will still be Jews. So we—my wife and I—are going to be here, too. Forever.

People have every right to be unable to distinguish between momentary disappointment and worry (which I share) on the one hand and the eternality of the Jewish home here on the other.

Believe what you want. But please, for the sake of the Jewish people, if you can’t distinguish between the two, so that we not only survive but flourish, please step aside and leave the leadership to those communal figures who are equipped, and fit to fill those sacred roles.

What changed? People are listening to this, and they're now understanding, okay, so you have a conversion process that is more or less parallel to the chief rabbinate’s process. It's completely Halachic. It's what people outside would call an Orthodox Halachic conversion process. It's much more user friendly. It allows for greater flexibility within the parameters of Halachha. And you're saying that there were lots of Israeli rabbis and maybe the Israeli norm until a couple of decades ago in which this would not have been so unusual. Now people have got to be asking themselves, what changed? How did it come to be that the chief rabbinate ended up being ultra-Orthodox, which, if you want to put a bit of an edge on it, the chief rabbinate might therefore not be Zionist. The children of the chief rabbis typically don't go to the army. So, you have a kind of a crazy world here in which the very best of the Zionist religious Zionist movement is now not reflected in the world of the rabbinate of the Jewish state. How did this change?

So, first, I want to make comments about whether they're Zionist or not. By virtue of the fact that they're not willing to address the conversion issue frontally, in my humble opinion, that makes them not Zionist, because I think conversion in this country today, and conversion, by the way, overseas as well, given the huge intermarriage rate, I think that's a Zionist project. I think you are failing the Zionist dream if you don't address where the Jewish people are at today. So, by definition, they're not Zionist. Whether they wear a black hat or a crochet kippah or sing Hatikvah on Yom Haatzmaut, I don't think they're part of a Zionist project at all. I think our conversion court is fundamentally a Zionist project as much as it is a religious project. What happened is a combination of a few factors. The first one is that the religious Zionist community chose to some extent to abandon their commitment to Jewish life and religious institutions in Israel. And here I'm going to use a political phrase that I don't like using so much, but they put their eggs in the basket of what is generally called I don't like this phrase, the settler movement.

You’re talking about the Gush Emunim period, right?

Right. The Gush Emunim period basically represents a watershed moment for the religious Zionists abandoning the chief rabbinate and saying this isn't so important to us, or as important as the Greater Israel is. And I'm not trying to deny yes, no greater Israel, I'm just saying that that was one factor.

And so, nature abhors a vacuum…

Exactly. The second thing was that the ultra-Orthodox, beginning in 1988, began to realize that they could wield significant power, and this was a natural place for them to begin. Right. They expanded way beyond that. And you can see in the, in the constellation of today's government where the ultra-Orthodox are very interested in, you know, the Ministry of Interior and certainly, you know, part of the government committees that relate to finances, et cetera. But correct. They filled a vacuum in that area. So, I think it was both an abandonment of, you know, where the religious Zionist community was, the previous leadership, previous generation of leadership of Yosef Burg, et cetera, those people who were very, very committed to having the religious dimensions of the state of Israel reflect part of the Zionist narrative. What I described before, the people who want to build the future based on the past, to people who just want to live in the past. So, they simply deny. And again, the past they're living in is not I think it's actually a made-up past. It's not a real past. And they say we're keeping conversion standards as they were for 2000 years. That's just a lie. It's just an outright lie. And what's worse is they know it. They know it that they're lying. They know that it's not okay. And by the way, I'm building on that. I'm building on the fact that they know ultimately, it's a lie. And I'll give you an example of it. The Chief Rabbis have both gone on record. They attack us all the time publicly, our conversion program, these people aren't Jewish, et cetera. So, I once said to one of the chief rabbi, I said, tell me something, if one of our converts from ITIM were to walk into your house on a Friday night and flip on the light, would you stay in the room? Or would you walk out of the room? Because Halachically speaking, you can't stay in the room. If a Jew flips on the light for you, you can't stay in the room. So, I sort of gave him pause obviously they recognize our converts are Jewish. So, when they get up and say publicly or in their Saturday night sermons they get up and say these people are all whatever and they used all sorts of evil words about us. I understand that we're a thorn in their side because they know we're doing something Halachic, and they know we're doing something that's totally legitimate and we're it not for political concerns they would be with us or they should be with us. So ultimately our long-term strategy in terms of ITIM and the conversion is to create facts on the ground such that it will be simply impossible. Look, whether it's 5000 converts or 10,000 converts or 20,000 converts, I can't say yet. And again, we'll need the political constellation to be in place. But I think there'll be opportunities in the future. And because of that I'm optimistic and we're going to continue, we're going to enhance and deepen our programming. Now some people are saying well what can we do now? They're throwing up their hands. I'm quite the opposite. We need to double down on what we're doing because we believe in it. We know it's the right thing to do and we know ultimately for the Zionist project and for the Jewish people project, our language and our approach is the way that has the best chance of not just survival, but growth and you know, augmenting who we are as a people.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.