"On the seventeenth of Tammuz, the walls were breached"

Those ancient texts we're often quick to dismiss beg us to ask a question that sounds almost blasphemous: How would we know when the end has begun?

A famous Mishnah in Ta’anit 4:6 explains the origins of the fast of the Seventeenth of Tammuz, which falls today:

Five calamitous matters occurred to our forefathers on the seventeenth of Tammuz, and five other disasters happened on the Ninth of Av. On the seventeenth of Tammuz the tablets were broken by Moses when he saw that the Jews had made the golden calf; the daily offering was nullified by the Roman authorities and was never sacrificed again; the city walls of Jerusalem were breached; the general Apostemos publicly burned a Torah scroll; and Manasseh placed an idol in the Sanctuary.

Two thousand years ago, the walls were breached on the 17th of Tammuz, and soon thereafter, it was all over. This year, the walls were breached on October 7.

It has long been common in many circles to argue that this period of the Three Weeks, beginning with the Seventeenth of Tammuz today and culminating with the Ninth of Av three weeks from today, is no longer relevant. Why would one mourn the breaching of Jerusalem’s walls, when the walls are anything but breached? Why would one mourn the destruction of the Temple when Jewish life in that ancient land is flourishing? Why would anyone recite any longer this passage from the Tisha B’Av liturgy:

Console, O Lord our God the mourners of Zion and the mourners of Jerusalem and the city that is in sorrow, laid waste scorned and desolate that grieves for the loss of its children that is laid waste of its dwellings

Fair enough. Jerusalem is not laid waste. And I would guess that most readers of this column do not yearn for the rebuilding of the Temple.

Still, for me, at least—and particularly this year—at the core of this period of the year lies a question that sounds almost blasphemous, but that we need to ask: How would we know when the end has begun?

Many of our non-Israeli friends are surprised when we tell them that at most of our Shabbat meals or social gatherings, whether they’re at our place or elsewhere, we hardly ever discuss the war. A mention here and there, of course, and without fail, inquiries about who has kids “in” and who has kids “going in soon.” Or “out.”

That sort of thing. But beyond that, what is there really to say? We all know the same things, and we all don’t know the same things. It’s here, it’s everywhere; do we need it at Shabbat lunch, too? So one of the things we talk about is what we’re reading. Some people say that they can’t focus on fiction—so they’re reading non-fiction. Others say that they need the respite from reality, so they’re reading lots of fiction.

I’m in the latter group. During the week, obviously, non-fiction for work and writing. On Shabbat and “down time,” though, I put all that aside and dive into the world of good fiction.

But here’s the thing about fiction—if it’s good fiction, it likely raises profound human questions that invariably lead us right back here. A few weeks ago, I read Paul Lynch’s extraordinarily beautiful and haunting novel, Prophet Song.

I didn’t know much about it when I picked it up (except that my wife, who’s responsible for “fiction acquisitions” in this household and who is very selective, had picked it up). Had I known more about it, maybe I would’ve thought twice. For a respite from thinking about this place, it definitely was not.

Here, it turns out, is what I would have known had I read about it on Amazon before starting it:

On a dark, wet evening in Dublin, scientist and mother-of-four Eilish Stack answers her front door to find two officers from Ireland’s newly formed secret police on her step. They have arrived to interrogate her husband, a trade unionist.

Ireland is falling apart, caught in the grip of a government turning towards tyranny. As the life she knows and the ones she loves disappear before her eyes, Eilish must contend with the dystopian logic of her new, unraveling country. How far will she go to save her family? And what—or who—is she willing to leave behind?

The winner of the Booker Prize 2023 and a critically acclaimed national bestseller, Prophet Song presents a terrifying and shocking vision of a country sliding into authoritarianism and a deeply human portrait of a mother’s fight to hold her family together.

The writing is extraordinary, literally breathtaking at moments. But dystopian novels about countries falling apart might not be the best choice at this moment. Especially since one encounters passages like this, when Eilish, the main character, speaks with a woman whose children have moved away (p. 235):

Oh, they’re long gone, both of them in Australia, they’ve been trying to get me to leave the longest while, but I don’t want to go. But why, Mrs Gaffney, why have you stayed? The woman is silent a long time. She put a mottled hand to her chin and goes to speak but sighs instead and looks away. Why do any of us stay? she says.

It’s one of those questions what one hears here, now and then, usually with a hush. As if it’s the sort of thing we’re not supposed to talk about, or know about—even as the papers are filled with articles about colonies of Israelis springing up in Cyprus, in Greece—and even a group of Israelis who have moved as a group to Tuscany, just as a century ago, Jews in Europe were forming small groups and moving here.

For for this period of The Three Weeks, we’ll be posting a podcast interview with a woman who survived October 7 with her husband and three small children in a safe room for fifteen hours—without electricity so that it was pitch black (a huge metal plate covers the windows of safe rooms), no phones (they’d died) and no air conditioning. Her family has now moved to the States, and she explains why.

It’s not only fiction. The crisis we are in is so profound, so far-reaching, and (for those who’re willing to be honest) so potentially calamitous that it colors everything.

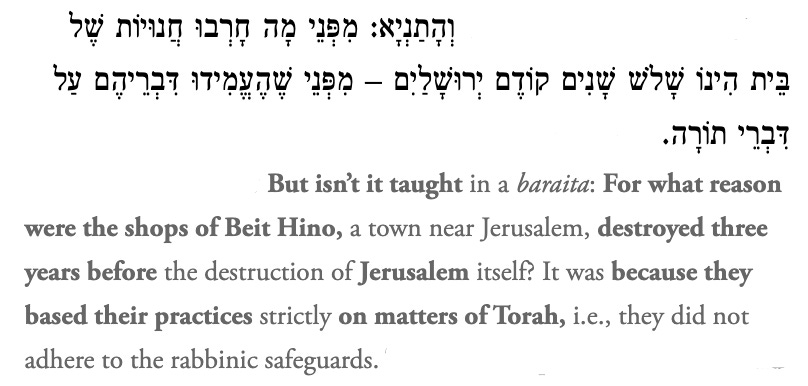

It can even be the study of the daily page of Talmud. A number of weeks ago, as we were in the last third of the tractate of Bava Metzi’a, we came across this passage at the very bottom of 88a.

I didn’t spend any time looking into what Beit Hino was back then, or who lived there, or why the shops there were of particular interest. But I remember thinking as we studied the passage that maybe the shops’ closing had nothing to do with “matters of Torah” over “rabbinic safeguards,” but instead, perhaps, because that was the part of the economy that tanked first. Jerusalem didn’t fall in a day, so to speak.

I thought about Beit Hino again last night. On the 8:00 pm TV news, there was a story about two families from Kiryat Shmonah, a city on the Lebanese border, who have moved their businesses from the north to Tel Aviv. One, a guy who fixed air conditioners in the north, said that there was no business—no one lives in the north anymore. So he decided to put to use the years of his mother teaching him to cook, and has opened a food establishment in Tel Aviv. He’s doing pretty well. When the reporter asked him whether he planned to move back when all this is over, he said, “What, and have terrorists pop out of the ground right behind my house?” The reporter asked his adult daughter if she would go back. “Never. I’d be too afraid,” she said.

They interviewed another guy who had a wine store, in the Hula Valley, that specialized in wines only from small wineries in the Galilee and the Golan. He had to move the store, he said, because there was too much Hezbollah shelling in the area, too many fires burning. And, of course, zero customers. He got a space in Tel Aviv, and moved all the wine there. He’s doing fine; he kind of likes the Tel Aviv vibe. Would he move back? He stared at the camera and shrugged.

It doesn’t take a vivid imagination to conjure the day when someone might ask,

For what reason were the shops of Kiryat Shmona, a town near the northern border, destroyed years before … whatever then happened.

As for that passage from the Ninth of Av liturgy that we’ll recite three weeks from today, how “irrelevant” is it to the world we now inhabit?

A city that is in sorrow? Which city of neighborhood in this country is not awash in grief, fear and sorrow?

Laid waste? All it takes is one visit to the Gaza envelope to know what “laid waste” looks like.

Scorned? Been to the UN or an American college campus lately?

Desolate? Talk to the handful of men who’ve stayed behind in their northern towns so they can fight the fire, while everyone else has left.Or the Gaza envelope? That’s what desolate looks like.

That grieves for the loss of its children? Not much to say about that. I heard a psychologist on the radio a few days ago saying that if the Bibas children are still alive in Gaza, the younger one likely has no memories of life before captivity.

As is commonly known, Israelis of all walks of life have been calling this war “The Second War of Independence.” On that, left (or what’s left of the left) and right seem to agree: Benjamin Netanyahu used that term as early as October; but the new head of the Labor Party, Yair Golan, said precisely the same thing. Lt. Col. Richard Hecht, IDF International Spokesman, called it that on our podcast interview with him. Yaakov Amidror, a former major general and National Security Advisor of Israel, agrees. The list goes on, and on.

Yet here’s the thing about this being a Second War of Independence. Yes, like in the first, a huge number of civilians casualties (most, obviously, on October 7). Yes, like in the first, Tel Aviv was attacked from the air (by Egyptian planes in 1948, and by a Houthi drone last week). Yes, like in the first, an opportunity for a new Israel to emerge.

But, we should also remember this about the War of Independence—for at least the first phases of the war, the outcome was far from clear. With the blurring of hindsight, we take Israel’s victory in the 1948 war (actually 1947-1949) for granted. But back then, for a good chunk of it, it was far from obvious that it would end in victory.

There’s something odd about Israel’s leaders calling this the Second War of Independence, and at the same time, the country having adopted the phrase Yachad Nenatze’ach, “We will win together.” Yachad Nenatze’ach projects a confidence that calling this the Second War of Independence ought not.

Israel will almost certainly win this war militarily. It looks like Hamas is teetering, though we might have to stay in Gaza for the very long haul to keep it that way. So far, the West Bank (Judea and Samaria) has not blown; perhaps we can keep matters that way. But the the north is completely unresolved. And as Judith Miller notes in Tablet Magazine:

Although Israel would ultimately win a war with Hezbollah, the price could be horrendous. While Hezbollah rockets and drones now fall on houses in northernmost towns like Metula, and set fields and forests on fire, they may well overwhelm Israel’s air defenses and level villages and parts of cities. Israel’s civilian death toll in such a war could easily dwarf the cost of Oct. 7.

After that, how many young families will decide that it just doesn’t make sense to raise their kids here? How many hi tech execs and others might choose quieter pastures for their endeavors? How many people will say what those store owners said—that they’re just not going to go back? Will we have won the war but lost the north? Won the other war but lost the south? Won the war but entirely burned out the reservists now speaking openly about how having been at war for more than 200 days, their jobs are in danger and their marriages are crumbling—so they imply may not be able to go back?

Yes, this might end OK. But for myriad reasons—domestic and international, military and diplomatic, economic and morale—it also might not.

That is precisely the point of these Three Weeks—a bit of historic and national humility is in order. We hope, but we do not know. Our kids are fighting like lions, but it’s not all in their control.

Do we hope, think, pray this will end like the First War of Independence? We do.

But do we know? We do not.

If there was ever a good reason for a period of Jewish mourning, this, I think, is it.

As we just had a granddaughter born in the States a few days ago, we’ve traveled to spend some time with our kids and the new addition.

So during what is the period of The Three Weeks on the Jewish calendar (the Seventeenth of Tammuz (July 23) through Tishav B’Av (August 13) we’ll be posting at a somewhat reduced rate.

But podcasts for our paid subscribers will continue as usual, and there will be other posts as well.

Unlike commenter Gary Kolb, I live here, in Jerusalem, having made aliyah from America 39 years ago. My only son was called up on Oct. 8 and served for 5 months and 11 days, and now suffers from PTSD. So I am commenting as an "insider." I have one question, Daniel: Where is God in your picture? Your negativity, your fear, comes from a perspective where God is simply absent. Can we save our current situation ourselves? Of course not! Our best aerial defense systems can protect us from only 90% of Hizbollah's missiles, and since they have 150,000, as you quote from Tablet, over 1,000 Jews could get killed. But what happened when Iran attacked us in April and 10% of their missiles did get through? Miraculously, those missiles landed in open areas (of which Israel has less than almost any country on earth) and not one Jew was killed or hurt. Even Ben Gurion said: "In Israel, if you don't believe in miracles, you're not a realist." The Second War of Independence? How did we win the first War of Independence, with 5 Arab armies attacking us and they were much better armed and trained? And the Six-Day War? And the Gulf War? Haven't we experienced enough miracles to make you have a little faith? Hashem will save us if we deserve it. And we deserve it by faith and unity, "B'yachad n'natzaeach." You are a religious person. Where is the God of Israel in your gloomy, doomy picture?

A year (or more) ago, one of my Zoom teachers (R. Menachem Leibtag) said we continue to mourn on on Tisha b'Av, not for *what* happened, but for *why* it happened.