"Surplus Jews" no longer

Eighty years ago this week, 700 Jews drowned because no one in the world would take them in

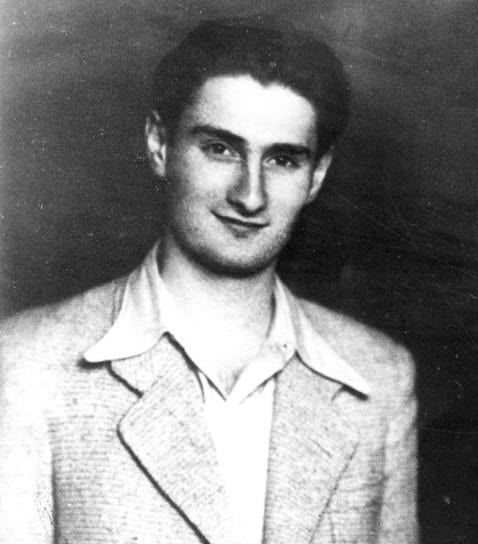

Eighty years ago this week, on February 24, 1942, nineteen-year-old David Stoliar was alive, alone, floating on a piece of wood in the middle of the Black Sea, surrounded by corpses, yelling all night into the dark so that he would not fall asleep and freeze to death.

He was in the Black Sea, surrounded by death, because he was a “surplus Jew,” as the British put it unabashedly. We’ll come back to David Stoliar.

Last week, the Israeli government was cooperating with relief groups to prepare for the possible evacuation to Israel of some of the 100,000 Jews in Ukraine, should the anticipated war make that necessary. Officials apparently do not expect to need a massive airlift, but they’re preparing for all eventualities, some said. Twenty-one years ago, as many of us vividly recall, Israel airlifted 14,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel on massive El Al jumbo jets. It was for the same reason. Ethiopian Jews, as far as Israel was concerned, were not “surplus.” Neither are the Ukrainian Jews.

And sure enough, this morning’s Israeli press announced that they had begun arriving. Dozens of olim from Ukraine arrived in Israel on Sunday as the threat of war grew ever ominous. According to the Ministry of Aliyah and Immigrant Absorption, 75 immigrants arrived on an initial flight and another 22 were expected the same day. Said Immigrant Absorption Minister Pnina Tamano-Shata, “Our message to the Jews of Ukraine is very clear — Israel will always be their home; our gates are open to them during normal times as well as in emergencies.”

Israel’s most important function is not serving as a refuge for Jews who need it. Nine-million people do not go about their business of living here and building this country so that one day, if Jews need a place to go, we’ll be here. Still, though, refuge is part of why Israel is around; the fact that there is a Jewish state means that there are no longer “surplus Jews.”

Which brings us back to David Stoliar.

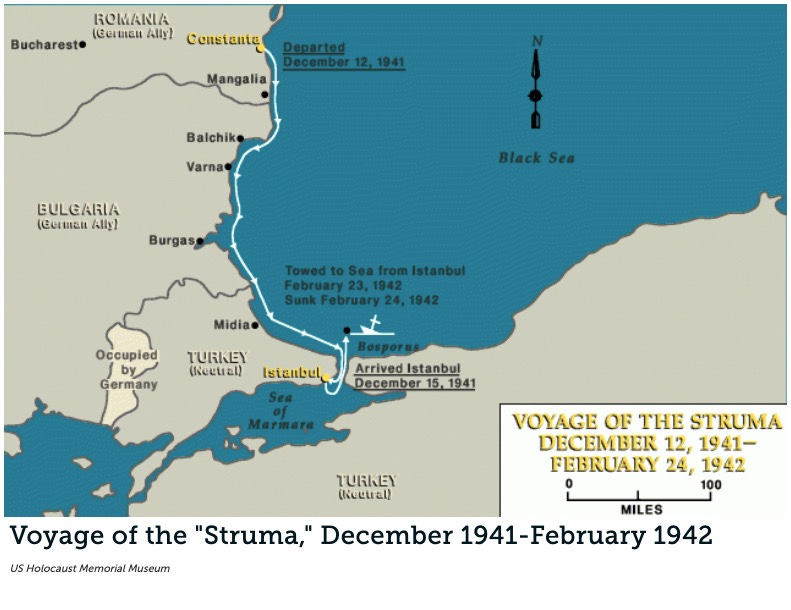

The story begins in 1941, by which point it was clear to many Eastern European Jews that they were destined for a horrific end. In Romania, several Zionist organizations, Betar (which had been headed by Menahem Begin, about whom we’ll write next week on the occasion of his 30th yahrzeit), among them, commissioned a Bulgarian ship—the Struma—to transport almost 800 Jewish passengers to Palestine. (We also mentioned the Struma in this column).

Like Europe, however, the Struma was a disaster waiting to happen. The ship was barely more than a floating tub, 61 meters in length and six meters wide; built in 1867 as a British luxury yacht, it had eventually been converted to transport cattle. It was powered by a motor that had apparently been salvaged from the bottom of the Danube River. The ship was equipped with only four sinks, one freshwater faucet, and eight toilet stalls for some 800 people. There was no toilet paper. More ominously, there were no life preservers.

Their only sources of comfort were the knowledge that they were finally succeeding in fleeing a burning Europe and that the whole trip to Istanbul, the first leg of their journey, would take merely 14 hours.

The Struma set sail on December 12, 1941, but the engine gave out almost immediately. The tugboat that had towed them out of the harbor eventually sent its navigator and engineer on board, but they would only fix the engine for a large sum of money. The passengers, however, had given all their money to the Romanian customs officials. So they parted with their gold wedding bands in return for the repairs.

The repair barely worked, however, and soon the engines gave out again. Four interminable days later, the boat limped into the Istanbul harbor, where it would remain for months.

Turkey refused to allow the passengers to disembark—after all, what country would want a boatload of homeless Jews? Nor did Britain want them to make their way to Palestine; the British were anxious to assure an increasingly restless and sometimes violent Arab resistance that limits on Jewish immigration would be enforced.

On February 12 (ironically, the very same day that British policemen apparently murdered Avraham Stern, about whom we wrote last week), almost two months after the boat had left Romania, the British grudgingly partially acquiesced and granted Palestinian visas to the children on board. But His Majesty’s government refused to send a ship to collect them, and Turkey refused to grant them overland passage. The children thus remained on board. With negotiations between Turkey and Britain at a standstill, Turkish officials towed the disabled boat up the Bosporus Strait toward the Black Sea.

Passengers hung signs over the side that said “Save Us” in both English and Hebrew. Though the signs were plainly visible to people on the shores of the Bosporus, no one, of course, did anything to help them.

When the hapless Struma reached the Black Sea, the Turks abandoned the ship, leaving it to drift. The next morning, on February 24, a Soviet submarine torpedoed the Struma, which exploded and sank. Of the 769 people on board, only one survived, by holding on to wreckage for more than 24 hours.

That survivor was David Stoliar. Locals on a rowboat eventually pulled him out of the water and wrapped him in blankets to warm him; they then took him to a small Turkish fishing village. Frostbitten, he was hospitalized in Istanbul, and then, apparently to prevent him from speaking to the media, was jailed by the Turks for six weeks. Eventually, Stoliar made it to Palestine in 1943, where he served in the Jewish brigade of the British Army and then in the IDF during the War of Independence. He became an oil executive and lived in Japan for eighteen years, and in 1971, moved to Oregon.

Stoliar didn’t speak about the incident much. When he died in 2014 at the age of 91, he and the Struma had been so forgotten that The New York Times was two years late publishing his obituary:

Perhaps the most important element of the story to remember is to be found in a British governmental communication from 1941, referring to the Jews who were desperate to escape Europe and who, the British rightly understood, would try to make their way to Palestine despite British objections. “We should have some alternative scheme in hand for disposing of these surplus Jews, who having escaped from persecution in Europe, are going to be kept in detention camps in British colonies,” the communication stated matter-of-factly.

It is in vogue in certain progressive circles for Jewish educators to declare that “the essence of Zionism is not a Jewish state in the land of Israel; it is a Jewish home in the land of Israel” or that “The notion that israel [sic] must exist … is predicated on the belief that eradicating global antisemitism is such an unattainable goal that we cannot exist elsewhere safely” (the latter quote the subject of this latest brouhaha in Westchester). It takes a moment like this, with many thousands of Jews about to be caught in the crosshairs, to remind us of how glib these worldviews, privileged by an illusion of safety that Jews elsewhere do not have the luxury of imagining, can only be expressed by those blind to centuries of Jewish history.

Ukrainian Jews are too busy this week preparing for the worst, wondering what will happen to their homes, their children, their lives. It has to be terrifying, in ways those of us observing from afar cannot begin to fathom. Jews in that part of the world have seen war before, have been caught many times in the crossfire of conflicts that have nothing to do with them. In the process, too many times to count, Jews have been murdered, plundered, massacred and forgotten.

Tragically, if Vladimir Putin wants to set that region ablaze, he can and he will. Innocent lives didn’t matter to the Soviets when they torpedoed the Struma, any more than innocent lives matter to the Russians today. The only difference is that this time, there’s a Jewish state. This time, there are no “surplus Jews.” This time, no one will be left in the freezing water, yelling into the dark of night, wondering why no one cares.

And that difference makes all the difference.

I have a very brief column in Mosaic Magazine this week that looks at two key sentences in Israel’s Declaration of Independence and shows that the accepted translations (including the “official” translation on the Knesset website) are essentially incorrect. How do we know what they really mean? It takes a bit of sleuthing with the Hebrew Bible, the book that Ben-Gurion knew so intimately.

You can read the column here.

A few weeks ago, William Daroff, CEO of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, wrote a very thoughtful column in which he suggested that Israel’s closing its skies to American Jews during Covid was an affront to a sacred relationship. I wasn’t sure that I completely agreed, but I admired his argument and his tone, and responded here. Daroff then responded to my response in this second Jerusalem Post column.

Defining the relationship between Israel and diaspora Jews has been a difficult and fraught mission ever since Israel was created. Diaspora Jews, after all, are clearly not citizens of the State of Israel. But then again, they’re not entirely “non-citizens” either. The Law of Return makes them “citizens in potentia,” and in many other ways, Israel calls on Diaspora Jews for support, time and again, in a way that it could call on no one else.

How, then, should we define this relationship? William Daroff and I sat for a conversation about that issue, in light of his thoughtful columns. Here’s a brief excerpt of our discussion. The full podcast will be posted on Thursday, as always, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.