The above recording and photo, released by the Ministry of Defense, show Defense Minister Yoav Gallant addressing a group of pilots last week. His voice is calm, but it masks alarm. As we will see below, the highest echelons of the army and the government are deeply concerned about the damage that has been done to the IDF’s fighting readiness, in light of the hundreds of reservists who are now refusing to serve (they are technically volunteers, so they cannot be forced to).

How serious is the damage? Below, we provide a transcript of a very brief segment of an Israeli podcast that attracted a great deal of attention on precisely that subject. Even the brief section we translate will give you a sense of the gravity of the situation, at least in the eyes of some.

Beyond the issue of fighting-readiness, many are wondering aloud whether this present military crisis spells the end of the notion of the IDF as the “people’s army.” After all, they point out, how much of a people’s army was it anyway, when the Haredim (11% of the population) and Israeli Arabs (about 20% of the population) by and large do not serve. Add to that religious women who do national service instead of army service and conscientious objectors (of which there are not a few) — and you get some fascinating numbers. According to the IDF’s statistics, among Jews, in 2021, the rate of those serving was:

31.4% for men

44.9% for women

How much of a people’s army is it, people ask. And has the recently politicization of the army killed what was left of that notion. Which raises the question — where did this notion of the “people’s army” come from? And can the IDF (and thus Israel) survive without it?

We begin this week with a look at the army, below. But first, this week’s schedule.

Here’s what we have planned for this week (subject to changes as the new cycle requires):

Monday (today): A column on the IDF, its combat reading in the face of many now refusing to service, and the notion of the IDF as "the people's army": when did the concept start, and did it just end?

Tuesday: There are those (including many on the right) who believe that just as the Second Intifada (2000-2004) spelled the death of the left, the crisis which the present coalition has created could spell doom for the right. We look at two takes on this … a posting by Asaf Sagiv, perhaps Israel’s foremost conservative public intellectual, and a news clip, which we will provide in English, interviewing Likud voters—who say that their Likud days may be over.

Wednesday: a new book, Israel's Declaration of Independence: The History and Political Theory of the Nation's Founding Moment, by Neil Rogachevsky and Dov Zigler, explores Israel's Declaration of Independence and the debates that accompanied the Jewish state’s founding. Our Wednesday podcast is a conversation with these two authors about their fascinating book.

Thursday: Chuck Freilich, a leading Israeli security expert, has appeared on the Israel from the Inside podcast before, This week we’re posting an additional podcast with Chuck, in which he discusses his new book, Israel and the Cyber Threat: How the Startup Nation Became a Global Cyber Power. Cyber warfare is the new front line — is Israel prepared?

The army is not pretending anymore — battle readiness has been harmed

The Israeli press, mostly in Hebrew but a bit in English, too, has been slowly warning its readers of worrisome developments in the IDF’s battle readiness. The following headline appeared in Haaretz a week ago.

More recently, the press has turned up the heat. Two days ago, Cabinet Member Avi Dichter, who has been in government for many years and is widely respected, admitted (as the headline below reads), “The problem of [battle] competence is worrying us all—including Netanyahu.”

The sub-headline of this article in N12 explained further:

The Cabinet member from the Likud explained in an interview the significance of the phenomenon of ‘not reporting’ [for reserve duty]. “There is a concern that when people finally do report, they will not be as competent as operational directives require.”

That line was an oblique reference to a now-quite-public discussion of the following question: for how many weeks can the reserve pilots not train and still be operationally fit? Some people are saying that after six weeks of not training, the pilots can no longer be used operationally. Some say eight weeks. It depends on the pilot, of course, the kind of plane, the kind of operation and more—but one point is clear:

The pilots’ unwillingness to report for training will not be resolved simply by their changing their minds. At some point—and depending on who you ask, that moment could be either very close or might even have passed—even if the pilots wanted to serve or were willing to serve, it would be too late.

How bad is the damage? As we will hear in the podcast from which we quote below, the IDF is not yet cancelling missions because its capacity has been reduced, but such cancellations are already being discussed. For those who would like to read further, we have also included a list of other articles and sources about the IDF’s battle readiness, at the very bottom of this post.

Beyond battle readiness, there’s another casualty—the notion of the IDF as a people’s army

As we noted above, for many years, Israelis have thought of the IDF as a “people’s army.” That has been a claim about more than the value of (theoretically) universal service—it was a description about how a small country could keep a military large enough for its defense. And the answer to that question was the reserves. Soldiers—mostly men, but not only—would continue to serve several weeks or even longer each year even after their formal discharge from their years of full time service, both so that they could remain battle-ready and also so as to deepen the ranks of the “standing army.”

In October 1956, merely seven years after independence, Israel was dragged into a war at the behest of England and France.

The war, which in British memory has become little more than an afterthought, actually figured in an episode of The Crown. For an assessment of how accurate The Crown was, read this article by Martin Kramer, which will also give you a terrific précis of the war’s roots.

When the war ended, Israel’s having captured the Sinai and then having been pressured by the US to return it almost immediately remained highly controversial. The Davar headlines on 7 December 1956 (Davar was the “workers’” newspaper that ceased printing in 1996) noted (in the yellow) that “Ben-Gurion explains Israel’s position on the matter of retreating [from Sinai]” and (in the green) that “mechanisms for contact between the IDF and UN forces have been established.”

But more germane to our subject was an opinion column buried in the middle of the paper that captures the ethos of the time:

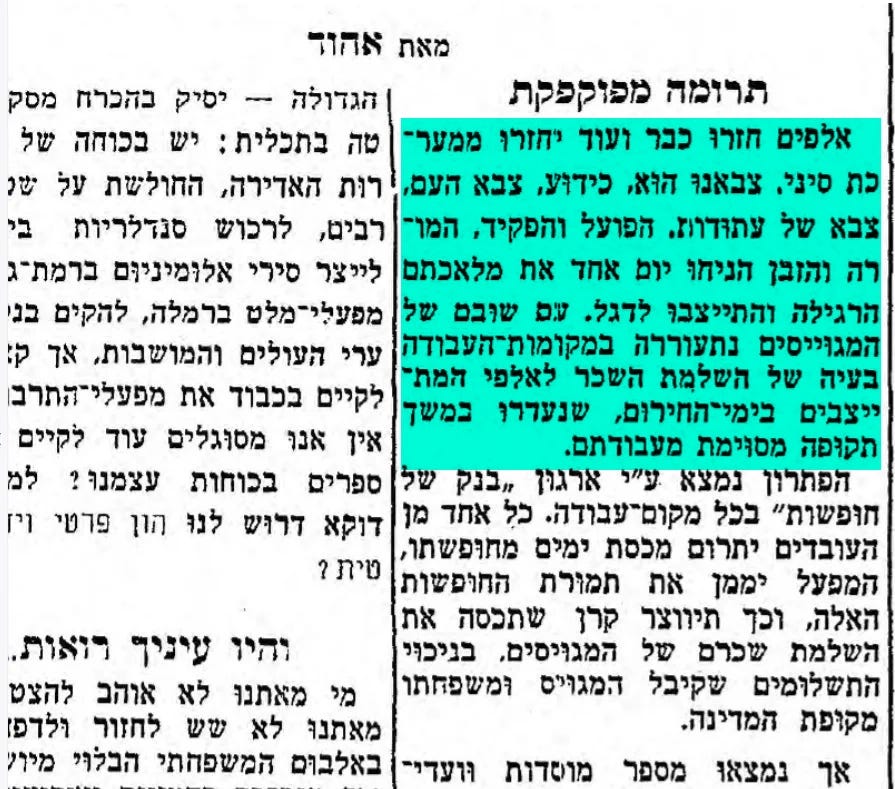

Thousands have returned, and more will continue to return, from the Sinai Operation. Our army, as is well known, is a people’s army, an army of reservists. The worker and the clerk, the teacher and the salesman, all dropped their work one day and reported to [serve] the flag. With the return of these draftees, an issue has arisen with regard to their workplaces paying the salaries of these thousands of men who reported during an emergency but as a result missed days of work.

According to some historical accounts, this was the column that made the notion of the “people’s army” the household term that it is today.

Now, though, any Israeli who reads that column of old would tell you that that ethos is gone. Whose fault that is depends on whom one asks.

Those deeply critical of the pilots (and others) refusing to serve say that they are the ones who destroyed the People’s Army. There was always an ethic here which said that when called upon, one served. It made no difference what one thought of the government or the war or the operation—you did what you were called on to do. These pilots, say the critics, destroyed that.

Those who support the pilots, on the other hand, insist that the pilots cannot be expected to put their lives in danger for a country that they are not confident will remain a democracy. Why risk falling into enemy captivity for a country that you’re not sure your children will be able to vote in, they ask. Those responsible, they counter, are the ones who sought to upend the democracy in the first place.

But no matter where one sides on the blame game, the ethos is dying. About that, there is very little disagreement.

As disturbing as that might be, even more worrisome is the possibility—discussed explicitly in this podcast, with a portion translated below—that the IDF is already considering cancelling certain operations because it no longer has the capabilities that it did just a few months ago.

Watch with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis to watch this video and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.