The Second Yom Kippur War

How we react to what happened on Monday in Tel Aviv will determine if we are worthy of the sacrifices made by those who fought in the first.

It was hot and humid when we gathered outside on Sunday night, in the courtyard of the community center about 100 yards from our house, for Kol Nidre. Despite the heat, the singing was nice and the mood was lovely—Yom Kippur was off to a good start.

And though no one mentioned it, we all felt it—hovering above everything transpiring there was the knowledge that this was the fiftieth anniversary of the war. Monday was half a century. Everyone there who is now in their sixties and above had either fought in the war, or remembered precisely where they were and what they did as the catastrophe began to unfold.

There was a sense of sanctity—and of gratitude—in the air. We’d won. The price was horrific, but that courtyard packed with people, secure and at home, was what those almost three thousand men had died to bequeath us.

I found myself praying that perhaps, just perhaps, they know somehow what made possible. I don’t know.

We were together through the next day, as well. By the the afternoon, when we gathered for Mincha, the weather had cooled, a gentle breeze bringing relief to everyone in the courtyard. Given the oppressive heat of the night before, it almost felt as if the weather was intimating that we’d been forgiven, that maybe the heat’s giving way to something more bearable was a metaphor for what might be in store?

And then, as the sun began to set and we continued into Neilah, new people began to arrive. First a few, then dozens … ultimately, I think, it was at least a hundred new people. Being in shul all day isn’t their thing, but being part of the Jewish people on the holiest day of the year is. So more and more plastic chairs keep magically appearing, and as the number of seats grew, so did the energy.

The person who led Neilah is a fabulous ba’al tefillah (leader of the service), with an uncanny ability to get those assembled to sing, to feel, even to weep. Those of us who know him knew that his family had suffered an unspeakably horrible tragedy this past year, so to see him standing there, singing his heart out and meaning every word he was saying, gave the moment indescribable power.

Obviously, in that setting on Yom Kippur, no one could film what was transpiring. But if in your mind the image of Yom Kippur is that of Yom Kippur in a typical diaspora synagogue, it can be hard to imagine the peak moments of Neilah in Israel.

Someone (I don’t know who) did take a quick video of the closing moments of Neilah at Yeshivat Sderot (possible since YK was technically over—they go long there). Though nothing is quite like Neilah at a yeshivah, the video will still give you a taste of what Neilah can be like throughout Israel, as it did where we were.

It’s a snippet of Avinu Malkenu from the very end of Neilah this past Monday evening. Here are the words:

אבינו מלכנו פתח שערי שמיים לתפילתנו Avinu Malkeinu, petach sha'arei shamayim li-tefilateinu "Our Father, Our King, open the gates of heaven to our prayer"

You finish Neilah not far from where the High Priest had safely exited the Holy of Holies, up the street from where battles for this city raged in 1948, and half a century after a horrible war but now, with the children and grandchildren of those killed among the assembled, singing their hearts out, and somehow, you emerge convinced that things will be OK.

Moments like that, with your son and grandson next to you, are the moments that life is about. From moments like that, you don’t walk home—you float home, more grateful than words can possibly express to be here, to live here of all places, fully cognizant that what you have just experienced doesn’t happen anywhere else on this planet. Anywhere.

But then we got home.

We had some orange juice and started to put out dinner.

We turned on our phones.

And it felt like the world had ended.

While we had been at prayer, Tel Aviv had turned into an ugly war zone of indescribable hatred. The most sacred day of the year had given expression to the most vile sentiments in which Israel has been awash all year.

I was so dumbfounded that I found myself staring at my phone endlessly. Everyone else was drinking, and eating—the fast had been long and hot. But I wasn’t hungry. I just kept flipping from news site to news site, so stunned and shattered that everything else was a blur. At a certain point, I started to put the lids back on the food containers and returned them to the fridge. “Abba, what are you doing? We’re still eating. Come and sit,” my son said.

I didn’t even realize people were still eating.

Nor could I sleep. At about 3:00 a.m., I realized I was hungry. So I went downstairs and drank some water, had a nibble. And at 4:00, I finally drifted off, the euphoria of the courtyard earlier that evening so obliterated that it was hard to remember that we’d felt it at all.

By now, what happened in Tel Aviv has been so widely covered that there’s no real need to review it. But just in case … a quick précis.

For several years now, an organization called Rosh Yehudi has conducted a Yom Kippur Service in Dizengoff Square in Tel Aviv. In most Orthodox synagogues, of course, the entire space is divided into an area for men and an area for women. But this one has always been different. The idea of Rosh Yehudi has always been to draw as many people as possible from the Tel Aviv world to Yom Kippur. The kernel of observant people would have their space with a mechitzah, and the rest of the large open space would be undefined; people would do what they wished. The organizers knew very well that men and women would be mixed, but they didn’t care—what they cared about was giving men and woman who are not Orthodox an opportunity to share in the powerful worship of Yom Kippur.

Last year, we posted a few videos of that very service, which someone who was there had sent me:

There’s “The Lord is King” section at the very end of the Yom Kippur liturgy:

and the blowing of the Shofar at the end of Yom Kippur:

So why was the gender-separated section permitted in years past but not this year? Because this year, Israel is awash in anger and resentment, and Tel Aviv’s secular mayor, Ron Huldai, decided to catch a wave on the anti-religious sentiment sweeping much of the nation (some gratuitous, outrageously provocative past comments by the heads of Rosh Yehudi in other contexts gave him ammo), and declared that the service could not proceed if there were any part that had a mechitzah, because the mechitzah on city-owned public space violates Tel Aviv law.

His ruling was appealed, but the lower court sided with the mayor. Tel Aviv has a law and the law is clear. No had one cared much in the past, and “live and let live” allowed the service to proceed back then; but this year, egged on by the mayor, people were demanding that the law be enforced. So when the case got to the Supreme Court, the Court sided with the lower court and rejected the request that the mechitzah be allowed.

Rosh Yehudi, the organization that organized the service and made Yom Kippur accessible to thousands of secular Israelis announced that they would not hold the service this year.

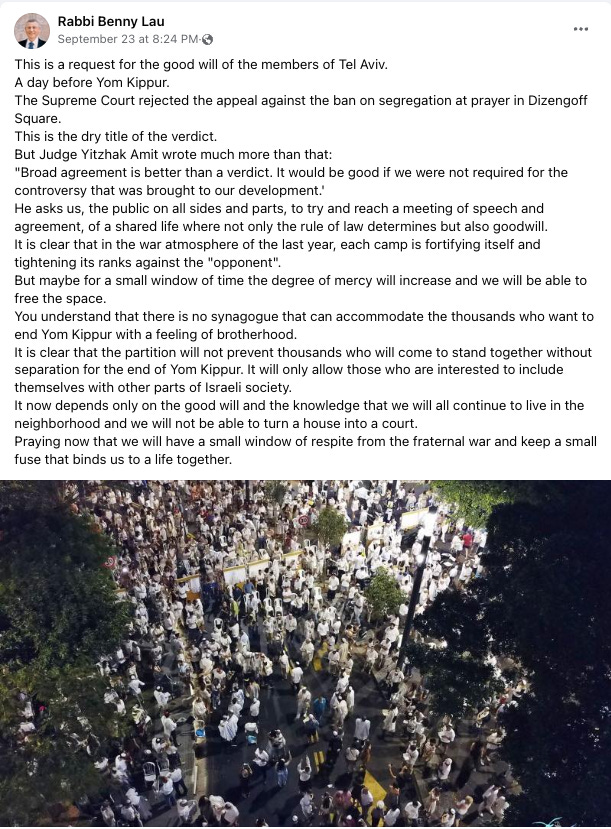

With tensions rising, some rabbinic figures pleaded that people use good judgement. Rabbi Benny Lau, one of the most profound, insightful and widely respected modern Orthodox voices in Israel, took to Facebook to make his plea (the following is a Google-generated translation of the Hebrew original), noting that even Justice Amit, who had issued the ruling, was hopeful that the citizens of the Jewish state could resolve an issue like this without relying on a black letter law ruling of a court.

But despite Rabbi Lau’s appeal that cooler minds prevail, the opposite happened. Rosh Yehudi decided to skirt the law (in good Talmudic fashion?) and to put up Israelis flags (a much-used symbol these days) to create a makeshift mechitzah. The police stayed away, but angry secular Tel Aviv residents were having none of it, and what resulted was so ugly that it left the entire country stunned.

Compare the scenes in the two YouTube videos of the Dizengoff Square service last year, with what unfolded this year:

In the background, drowned out by the word booshah (“you should be ashamed”) you can hear the Cantor trying to continue, but he soon gave up. The organizers moved the service to a nearby synagogue, but it was small—the many hundreds who could have had the experience from last year were robbed.

The person who sent me those videos last year was at Dizengoff Square again this year. He told me that Jews were screaming at other Jews on Yom Kippur, calling them “Nazis.” The scene (and dozens of videos that made their way around Israeli society media) left the country stunned, heartbroken, despondent.

Compare last year and this year, people said, and there’s good reason to wonder: has the civil war finally started?

President Herzog said, in no uncertain terms, that the country was coming unglued.

How did we get to this terrible situation, in which 50 years after that bitter war, sisters and brothers stand on opposite sides of the divide? Those who pour fuel onto this fire are a real threat to Israeli unity. It has to stop here and now. The division, the polarization, the never-ending disputes — they are a true danger to Israeli society and to the security of the State of Israel. …

“The enemies of Israel are commenting about this repeatedly and referring to the internal crisis within us as the beginning of the crumbling of the State of Israel; and even though they are completely wrong, we must come to our senses, soften the tone, listen, reach out, and end the internal crisis we are in through dialogue and agreement.

Rabbi Lau had tried before Yom Kippur and President Herzog tried after Yom Kippur—both begged Israelis not to lose their minds, for if they did, they would lose their country, too.

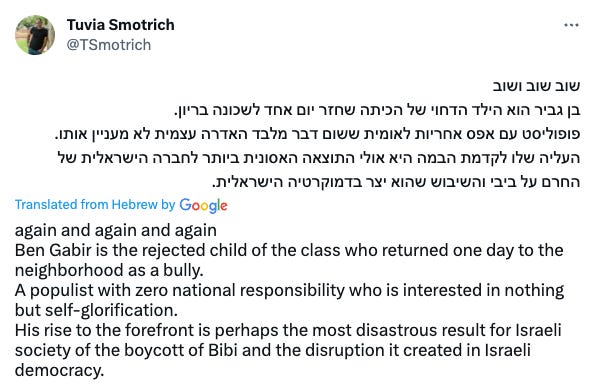

Yet cooler minds have not prevailed here in a long time. The Prime Minister, just back from his brewing bromance with the Saudis, sought to firm up his right wing base, which he’ll need if he’s to get any potential deal through:

Equally true to form, Itamar Ben Gvir, head of the Jewish Power Party, immediately announced a Thursday evening service in which they would “take back Tel Aviv” have a service with a mechitzah, law or no law.

“Let’s see you trying to evict us,” the Hebrew read (Google translate is good but far from perfect, obviously).

The Prime Minister took sides, Ben-Gvir promised what would have caused a riot, and indeed, it seemed that Herzog was right—on the holiest day of the year, half a century after the worst war in Israel’s history, we had now become our own worst enemy.

Forty weeks of peaceful protests didn’t mean anything. Rumors of compromise on judicial reform were either fanciful or irrelevant—because if we just hate each other, it doesn’t really matter how much power the Supreme Court hasf, does it? If we just hate each other, we’re not going to make it.

I lost track of the number of people with whom I spoke the next day, who were as brokenhearted as I was, who said to me, “We should really be honest. The experiment that is this state is failing. Sooner or later, and probably sooner, it’ll be a memory.”

Or, maybe not?

Suddenly, just as it seemed like everything was, truly, falling apart, voices who had been anything but moderate for a year begged Ben Gvir to stand down.

Simcha Rothman, one of the two people at the very core of the Judicial Reform movement, a man of the hard right, told Ben Gvir not to be a provocateur:

Ohed Tal, an MK from Bezalel Smotrich’s Religious Zionism party, similarly begged Ben Gvir to let the country heal.

So, too, did Smotrich’s brother:

Had Yom Kippur brought us close enough to the brink of something so terrifying that people finally realized what’s being destroyed? “All these right wing figures telling Ben Gvir to stand down, that the country is hurting enough, that this isn’t about getting a ‘win’ three days after Yom Kippur—that has to mean something, doesn’t it?” we assured each other in the hallways at work.

And sure enough, yesterday (Wednesday afternoon), Ben Gvir announced that he was cancelling the protest/prayer service.

Yet we all know that was a likely a mere reprieve. The “service” was cancelled, but the hate was not.

Ron Huldai, Tel Aviv’s mayor, will get no political benefit from the hate-storm he unleashed. Rosh Yehudi, not terribly well known before, has had its vile statements about secular Jews (despite the beauty of their Tel Aviv YK services) exposed anew. They’re not winners, either.

But the biggest losers will probably be the protest movement. The leaders of the protests have worked tirelessly to forge a broad-based coalition, an amalgam of people of very different views who simply want to preserve a system of checks and balances in Israel’s government. Many on the center and “soft-right” worried that they were joining in protest with people who hate them for being centrists, or for being religious, but they convinced themselves that it was worth giving the movement a chance.

How many of those religious protesters are going to be back in the streets? It’s too early to know, but the protest movement has been furiously trying to limit the damage, seeking to stem the bleeding by issuing (to my mind, rather bland) statements calling out everyone for having contributed to Yom Kippur’s catastrophe.

But no statements by anyone, no cancelled services or counter-protests, can change what everyone here knows and now can’t deny—this is a country filled with people who hate each other.

Not everyone, but far too many.

And unless something dramatic changes, this can’t hold. Not for very long.

“What do we do now?” is how the water-cooler conversations have ended this week.

Could some force for tolerance emerge? “It has to stop, here and now,” President Herzog said, quite rightly. But he’s been saying that for ten months. And who’s listened?

For a moment, there’s not much that this tear-rinsed nation, still in shock from the horrors of Yom Kippur in Tel Aviv, can do. Many want to do something, but few have any real ideas.

Perhaps we ought to revisit the closing moments of those Yom Kippur services that were not sullied, and seek refuge in the words we’ve been saying for many centuries:

אבינו מלכנו פתח שערי שמיים לתפילתנו Avinu Malkeinu, petach sha'arei shamayim li-tefilateinu "Our Father, Our King, open the gates of heaven to our prayer"

Even those not predisposed to prayer would probably admit that the time has come to gaze to heaven for help. For left to our own devices, Monday showed us clearly where we are heading.

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Our Twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Our Threads feed is danielgordis. We’ll start to use it more shortly.