"The winter of '73"

A song ... and the war that continues to haunt even today's young Israelis

For a book I’m now writing, I wanted to do some “market testing” of how different populations think about various dimensions of Israel. One of the groups I tested was a volunteer set of Israeli college students. I asked them to respond, without overthinking things, to a variety of questions, only two of which I will mention here.

The first question I asked was what they thought were Israel’s greatest accomplishments. The screen shot above is taken from the “word cloud” of their responses. The two responses that were most frequently mentioned (hence they are closer to the center and in larger letters) were “absorption of immigrants” (orange arrow) and “the IDF” (blue arrow).

What would you guess would be the answers of Jewish American college students? That’s for a different time.

But as we were chatting about their results, I noticed that the Abraham Accords (yellow arrow) made it in. Not near the center, but still in. That struck me as interesting. “Why,” I asked them, “do you think people mentioned the Abraham Accords, but no one mentioned Israel’s peace treaties with Egypt or Jordan?”

“Because that happened before we were born,” they said almost unanimously. “We were born into it … so we don’t think about it.”

So I pointed to their answers to the second question, which was, “what have been some of Israel’s greatest failures?” Here’s how they answered that one:

The “winner” (orange arrow) reads “Yom Kippur,” by which they meant “Yom Kippur War.” (The Palestinian issue also ranked very high, but since they phrased their answers on that in a variety of different ways (see all the little green arrows), the subject didn’t get the big font or center stage.)

So, I asked them, “But you weren’t alive for the Yom Kippur War, either. So why does that figure so centrally, while peace with Egypt and Jordan don’t?” Here, their explanations were less unanimous, but that, too, is for a different time. I was struck by the fact that young people, about 23 - 28 years old and thus born between 1993 and 1998, feel profoundly shaped by a war that happened a quarter of a century before they were born—but not by the peace treaties that followed.

I felt more vindicated than surprised. When I wrote my history of Israel, I included a line that said “In many ways, the Yom Kippur War irrevocably shattered part of Israel’s soul” (page 319). A number of my friends and colleagues who read early drafts thought that was an exaggerated claim, especially since Israel had “won” the war at the end. They said that I should take the line out. I was certain that it was not at all exaggerated, and believed that the shattering of Israel’s soul had not been healed by whatever “win” there had been. The line obviously stayed in.

While my little exercise last month was hardly sophisticated social science research (it served the specific purpose I had in mind, that too for a different time), the response of these young people convinced me, once again, that one cannot understand Israel, even today, if one doesn’t appreciate what the Yom Kippur War did—and still does—to Israel’s soul.

It was in light of the students’ responses a few weeks ago that I thought of one of Israel’s most moving songs about the war, “The winter of ‘73.” The song was first performed on Independence Day of 1994; to this day, it stirs the hearts of Israelis everywhere.

So I thought, especially with bitter storms due in Israel this week—so winter is definitely here, that this was a perfect time to introduce the song to those who do not know it, or may not have thought about it much.

This first clip is the only version that I could find with English subtitles. I would have translated parts of it slightly differently, but it’s “good enough for jazz.” With one exception: the opening “explanation” says that the song was sung by soldiers who were born in the winter of 1973, when the song specifically claims to be the voice of those who were conceived in 1973. There’s a difference, and in this song it matters.

But the rest of video more or less works, so let’s start with that.

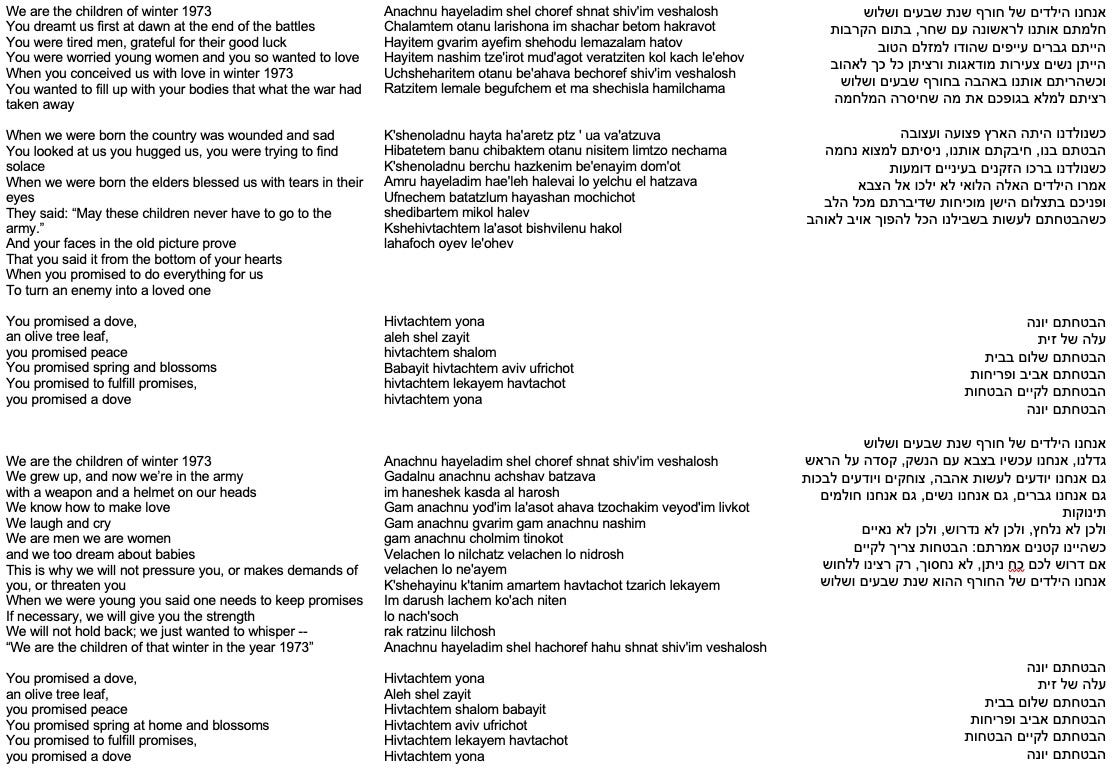

The song was first performed by the musical troupe of the IDF’s Education Corps, in April 1994. Here, so you can follow along with the next clips, are the words to the song and a translation:1

And here’s a recording of the very first performance of the song:

In April 2011 (on Memorial Day for Fallen Soldiers), the four original performers got together to perform the song again; by then, they were about forty years old. But you can still recognize their faces, and their voices hadn’t changed much.

What was different, was that by then, the song had become a kind of anthem in Israel. If you don’t want to watch the whole thing (it’s only six minutes), then at least take a glance at these moments:

00:53-00:56—Watch the father, a tear on his face, with his child in his lap

01:46-01:56—Look at the faces of the people

2:55-3:06—Notice how by now, everyone knows the words

A few last thoughts about that first performance in 1994. By April 1994, when the song was introduced, Israel had already signed a peace treaty with Egypt. Negotiations with Jordan were under way, and peace with Jordan would come at the end of 1994. “You promised peace, an olive tree … you promised to keep your promises.”

In many respects, Israel had done that. (The soldier interviewed in the second clip at 5:11 acknowledges that, with profound gratitude.) By the time the song appeared, Israel was essentially no longer at war with the countries that had attacked in October 1973. Egypt had signed. Jordan was about to. Syria was no longer a viable threat. It was over …

Except that around here, it’s never over. Those four young soldiers obviously couldn’t have known that a year and a half after their performance, Yitzchak Rabin would be murdered. There was peace on the outside, but not inside. Nor could they have known that three years after Rabin’s death, Israel would be embroiled in the Second Intifada for four bloody years. Or that twenty five years after they sang, Iran would be threatening to wipe out the Jewish state.

If you read Hebrew, look at all those responses to the first question (the slide at the very top). It’s unbelievable, that list of all the things that today’s young Israelis believe the country has accomplished. A home for the Jewish people. A safe haven for the Jewish people. The rebirth of the Jewish people. A thriving Jewish culture. Immigration. The ability of Jews to defend themselves. Peace with some countries …. the list goes on.

[We’ll post a more detailed discussion of those responses in coming weeks, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.]

We don’t have peace yet, that’s true (and no one here is holding their breath). But as powerful and moving as “The Winter of ‘73” is, the truth is, that in many, many ways, young people in this country believe that Israel is a country that does keep many of its promises.

Especially when you think about the purposes for which this country was created, they’re right.

It‘s time to transform Israel into a theocracy …. the worldview of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh; a conversation with Mordy Miller

If you've not heard of Rabbi Yitzchak Feivish Ginsburgh, the American-born rabbi somewhat associated with Chabad but with a unique worldview all his own, you're not alone. Outside Israel, he's not terribly well known. Inside Israel, though, he has an enormous following, thanks to his charisma, his brilliance, his phenomenal skills as a teacher of Torah. All good. ...

Except, perhaps, for pesky little details like his endorsement of a book that legitimates the killing of Palestinian children (because they could one day grow up to be our enemies) and perhaps even more worrisome, if that's possible, the fact that he believes--and says--that it's time for Israel not to be a democracy, but instead, to become a theocracy.

What's this all about?

In the first of two conversations, each dealing with a different rabbi representing streams largely unknown outside Israel, Mordy Miller, a doctoral candidate at Hebrew University who is an expert in these streams of Israeli religious life, takes us through the life and thought of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh.

This is a brief excerpt of our conversation with Mordy ... the full episode will be posted on Thursday, as always, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Translation and transliteration from http://www.hebrewsongs.com/?song=chorefshivimveshalosh, though I’ve modified the translation in places. The Hebrew words are taken from https://mshironet.mako.co.il/artist?type=lyrics&lang=1&wrkid=1427&prfid=2570&song_title=7b8e6

When I hear 'you promised,' I am reminded of "Ani mavtiah lakh,... shezot tihyeh hamilhamah ha-aharonah." [sorry my PC doesn't 'speak' Heb.]

The song's tune is very moving, but its lyrics are terrible. In essence, the song is sung from the point of view of children of the left, who blame their elders for the lack of peace. It's true that most of the country now realizes that the starry-eyed optimism which proliferated in the past within many (and much more so in the early and mid-90's than after the Yom Kippur War) was totally misplaced. But the lyrics seem to blame the failure to achieve peace on their elders, when the truth is that the overwhelming blame should be laid at the feet of our "partners". This mistake is even worse than the mistake of those who believed, in the early 90's, that the other side is ready for peace.