Throughout Israel's history, which massive protests have worked, and which have not? Here's one possibility ...

Part II of our brief history of Israeli protests

Shortly after my biography of Menachem Begin was published, Begin’s son, Benny Begin, called me and asked to meet. Our several-hours-long meeting is one that I will never forget, for a host of reasons, one of which is related to protests, and which I will share below.

But first, a brief look at where we are.

It’s far from over, this judicial reform issue (or “regime change,” depending of course on who you ask). It could still play out in many ways, some good, some bad, some much worse. But if you’re a betting person, the smart money is that judicial reform dies.

How Bibi does that without losing his coalition is not clear. Whether he might try to get some small version of judicial reform through the Knesset by force of his still-intact majority (it’s worth remembering that before the protests, most people in the know across the political spectrum believed that some reform of the present system is very much in order) and thus save face and preserve his partnerships with Yariv Levin and Simcha Rothman is also not clear. Even less clear is whether the protesters, who smell victory, would allow that without bringing the country to a screeching halt. Will the President’s negotiations do any good? Are the protesters in the mood for any compromise at all? It would be good if they were, but on that score, sadly, the smart betting money is that they are not. The protests worked, they believe, and with the wind at their backs, with Gantz outpolling Bibi with still increasing margins, they see no reason to give in on anything. That’s very unfortunate, but a subject for a different day.

Even with the future unknown, though, the apparent of the protests (that have now been sustained about 150 days, or 22 weeks) affords us a moment to continue our brief history of protests in Israel, looking at that those that worked, and those that didn’t.

Which brings me back to Benny Begin. Last week, we wrote about the famous protest that Menachem Begin led against the idea of Israel’s accepting German reparations. As we saw, the protest in Jerusalem got out of hand, grew violent, led to a disruption of the proceedings of the Knesset, got Begin (temporarily) suspended from the Knesset. And the protest failed.

When the chaos ended, the government decided to accept the German money.

Benny Begin had a long, long list of items from my book that he wanted to discuss with me, some technical, some much more conceptual. About some we ended up agreeing, about many we did not. That’s fine.

But as he worked his way through his long, written list, we got to the chapter on German reparations. “You were very hard on Ben-Gurion in that chapter,” he said. I was shocked. Benny Begin has devoted much of his life to honoring his extraordinary father’s contributions to Israel’s history and soul, and here he was, when we were discussing one of the formative moments in his father’s career, gently chastising me for having “taken his father’s side” in my description of the proceedings.

“I don’t think I was gratuitously hard on Ben-Gurion,” I replied to him. “I was simply trying to make clear the view of Jewish history that animated your father’s objections to accepting the reparations.”

Benny Begin paused, and then said softly, “I hear you. But my father didn’t have to feed anyone. He didn’t have to put a roof over anyone’s head. That was the luxury of being the head of the opposition. Feeding and housing people was Ben-Gurion’s problem, because he was Prime Minister. And Israel had absolutely no money. What else could Ben-Gurion possibly have done?”

Almost a decade later, my recollections of that conversation still take my breath away. I’m still struck by the judicious, balanced, fair read of history, the understanding of the “other side.” The recognition that love of Israel can manifest itself in different, sometimes diametrically opposed ways. And that justice and commitment to principle rarely reside exclusively on one side alone.

If Benny Begin were at the head of the protest movement today, we might end up with a very different outcome.

Did Menachem Begin’s protest against reparations really “fail”? On the surface, of course, it did. He demanded that the government turn down the money, but Israel accepted the “German blood money” and climbed out of poverty. It bought heavy duty cranes and bulldozers it had not previously owned and then built the national water carrier, created a national airline, a national shipping line, upgraded its military and much more. The German money saved Israel, and ultimately, it was that money that began the paving of the way to the technological, military and economic engine that Israel is today.

Still, though, Menachem Begin’s objections to the reparations indelibly imprinted on Israeli society a recognition that policy-making in the Jewish state had to be imbued with a sense of Jewish history, with a commitment to the self-respect that national sovereignty was meant to create. For many Israelis, Begin’s powerful speeches from that period still echo, and the competing speeches of Begin and Ben-Gurion still remind us of the shared passion and love—and correctness—that can lie at the heart of radically opposed policy proposals.

So yes, Begin’s protest failed, but not entirely. What about other Israeli protests? Did they work?

If one wishes to think of a protest that did work, one that did make a huge difference in Israeli policy, what comes to mind is the protest of the Four Mothers. Their protests, which ultimately helped end the Lebanon War, begin with a horrific IDF tragedy still emblazoned on the memories of almost every Israeli who was old enough to understand what had happened.

On February 4, 1997, two Israeli Yasur (CH-53) helicopters crashed in the Golan Heights on their way to southern Lebanon, killing all 73 soldiers on board. The soldiers had been on their way to their military outposts in the security zone. One was flying to the Pumpkin post (if you’ve not read Matti Friedman’s Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier's Story of a Forgotten War, which is about that outpost, you absolutely should. It’s a beautiful, exquisite book). The other helicopter was meant to fly to the Beaufort post.

The flight had been postponed the previous day because of weather conditions and rescheduled for the 4th. To this day, despite endless investigations, the army has provided no conclusive explanation of the cause of the crash. Many of us, though, remember precisely where we were when we heard about the crash. Some of us still recall the testimony of the first responders who got there, who found dozens of dead soldiers, but perhaps worse, more than a few still dying. (Many of those responders still suffer from post-trauma. One of the first medics to arrive at the scene took his own life in 2019, twenty-two years after the crash.)

The newspapers from that week have become iconic Israeli images.

Though the Lebanon War had been controversial for quite some time (Israel had been in Lebanon for about fifteen years at the time of the crash, with almost nothing to show for the lives that had been lost), the seeming senselessness of the mass casualties led four mothers who had sons serving to decide that enough was enough. The women were the founder, Rachel Ben Dor, Miri Sela, Ronit Nahmias and Zahara Antebi. They took the name of their movement, obviously, from the Jewish tradition’s reference to the biblical “four mothers”: Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah.

In many ways, some of the tactics of this year’s protests are reminiscent of what the “Four Mothers” movement did. They held protests at the border and set up demonstrations outside the Ministry of Defense in Tel Aviv. They distributed stickers at major traffic junctions throughout the country, held silent vigils in numerous locations, lobbied President Ezer Weizmann (himself a former commander of the Air Force and a nephew of Israel’s first President, Chaim Weizmann) as well as other ministers and members of Knesset. They collected thousands upon thousands of signatures of citizens urging for withdrawal. They were relentless. They were dogged.

The purpose of their protests was to shape a different national consensus. And yes, they were advocating a policy opposed to that of the democratically elected Knesset. Today, it seems patently obvious that they were right; then, at least at the beginning, it didn’t.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that because the leaders of the movement were all women, they are credited with having enhanced the image and role of women in Israeli public life. Today, the fact that Shikma Bressler, the Israeli basketball player turned leading physicist turned social activist now among the leaders of the protests is a woman seems entirely unremarkable. That, too, is partly the result of the Four Mothers. The Four Mothers also permanently uprooted the long-accepted image of the stoic, silent Israeli soldier’s mother who assumed that the state had her son’s best interests at heart, and in that, too, changed not only the course of Israeli history but one of the fundamentals of Israeli society, no less.

When the helicopters crashed, Israel had been at war in Lebanon for fifteen years. Just over three years later, on May 24, 2000, Israel pulled out of its military outposts in southern Lebanon, eighteen years after it had gone in. The soldiers atop the APC’s the rumbled out of Lebanon and back into Israel (equally iconic Israeli images) had been born just as Israel had gone in. And their mothers had gotten them out.

For those interested, here are some resources about the Four Mothers protest: a video, The Woman Who Got Us Out of Lebanon [w/ English subtitles by the New Israel Fund], or Four Mothers (trailer) w/ English subtitles, or a video showing protestors lined up against the border, or this page which was created by Rachel Ben-Dor, which is an entire archives of the Four Mothers protests (articles, interviews, video, etc.)

The cost of food is soaring in Israel this summer, and though the present government has promised to address it, nothing has changed. Quite the contrary, in fact. So why has the cost of living not become a major focus of the protests now unfolding? There are many reasons, but among them, I suspect, is the fact that another major Israeli protest did focus on the cost of food, and ultimately, despite massive numbers of protesters, it failed.

It all started in June 2011. An Orthodox resident of Bnei Brak named Itzik Alrov wrote a Facebook post about the high cost of cottage cheese. The price of cottage cheese—a staple of many Israelis’ diets—had reached about 8 NIS, which was a 45% increase in three years.

When his post went viral, the cottage cheese boycott was born. The high cost of housing was soon another focus of the movement, and by August, two months after Alrov’s Facebook post, hundreds (if not thousands) of people were living in tents on Tel Aviv’s central Rothschild Boulevard as a symbolic statement that they could not afford to buy housing.

On the cottage cheese front, the call to arms was simple: don’t buy cottage cheese that costs more than 5 NIS. Shortly thereafter, Tnuva and Strauss, among Israel’s main producers of dairy products, announced that they would lower the costs of the cheese.

Ultimately, the protests drew about 450,000 people into the streets, about twice as many as have been protesting over these past few months. But economic market forces are less easily subdued than legislative agendas, it would seem. The cottage cheese and Rothschild tent-city protests came and went, but in the end, they accomplished very little.

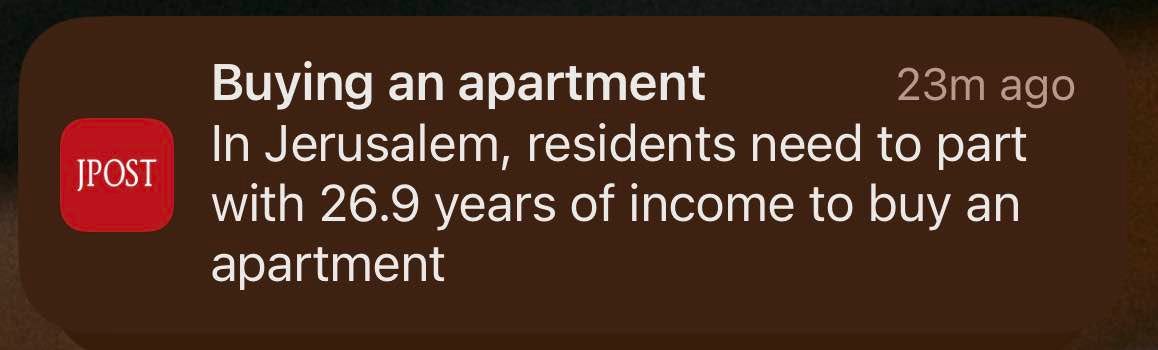

Just this week, in fact, the Jerusalem Post shared a rather chilling statistic about the cost of housing in Jerusalem:

The numbers might be a bit more extreme in Jerusalem than in other places, but the challenge to young Israelis trying to buy an apartment isn’t all that different in many others places. The young are frustrated, some are leaving. And how has this government responded? “There is always talk of a housing crisis… and I do not know that there is a crisis. I see construction cranes throughout the country,” the Haredi incoming Housing Minister Yitzhak Goldknopf said in December.

It was a pretty good indication of how out of touch this government would be with popular sentiment, which became obvious only weeks later when the proposed judicial reform sent hundreds of thousands of people into the street.

####

How are we to explain which protests work and which do not? There are many factors, of course, and each instance differs in countless ways. But I recall, during the cottage cheese protests, being stunned that the leaders of the protest had nothing to say about the Jewish character of Israel. They could easily have tied the demand for more affordable housing to a vision for Israel, or to their own commitments to the Jewish state, but they did not. They could easily have drawn a connection between food equality and the values of the Jewish tradition, but they did not. Go back and reread their speech, and if they’d been given in French, they’d have worked just fine in Paris.

There was nothing particularly Jewish about them, and sadly, little progress was made.

That was of course not the case between Menachem Begin and David Ben-Gurion, and it is not the case today. Taking the flag as their symbol was a brilliant move on the part of the protesters … that many of the speeches at many of the protests speak about protecting minorities as a key function of the courts and then remind the listeners of the visions of the prophets, about their demands that we protect the widow, the orphan, the stranger—it has been a carefully concerted effort to make it clear that these protests are Zionist, and that they are deeply Jewish.

If the protests work and judicial reform (mostly) goes away, will that have been the deciding factor? We won’t know for many years, until we can look back with some distance on what is unfolding now.

But if Zionism and Jewishness are key to successful Israeli protests, that would be a wonderful statement about the Jewish state. And it would be something worth noting on the part of those who will lead the protests of the future.

There has been, in recent months, discussions of the “nuclear moment” in judicial reform. What happens if the Knesset strips the Supreme Court of the right to judicial review, but the Court then overrules that law? Who is in charge? To whom does the army report? That, people say, could be the ultimate “constitutional crisis.”

A group of leading Israeli political scientists gathered together to participate in a simulation of what might happen. What they learned was interesting, and in this week’s podcast, we’ll speak with one of the participants, Avishay Ben Sasson - Gordis (yes, my son-in-law), a lecturer in political science at Harvard.

The podcast will be available, with a transcript, to paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside. We’ll send a brief excerpt to everyone.

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

How many of you have read Gadi Taub's scathing indictment of the Ashkenazi elites who are driving this protest movement? https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/israel-civil-rights-movement-ashkenazi-mizrachi

And why is Daniel Gordis, usually so fair and clear-minded, demonstrating with them?