Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

Avraham Stern, the Warrior-Poet killed by the British

Eighty years after his death, what is the source of the increased interest in his life and views?

Eighty years ago this weekend, on February 12, 1942, British policemen got a tip that Avraham (“Yair”) Stern, who headed the Jewish military underground group known as the Lehi (Lohamei Herut Israel, “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel”), was hiding in an apartment in the Florentine neighborhood of Tel Aviv. Officers burst into the apartment and found Stern hiding there. Stern (or “Yair”, as he was commonly known) was bound with his hands behind his back and placed on a sofa. Everyone else in the apartment was told to leave, but as soon as they exited, they heard three shots.

Avraham Stern was dead.

The official British version of events claims that he had tried to escape by bolting for a window, but the prevailing assumption among his then colleagues (supported by testimony from one of the British officers) was, and is, that he was murdered in cold blood.

It would not be surprising that the British would want him dead. The Lehi (which the British referred to as the “Stern gang,” a name that has unfortunately stuck among many) was considered the most radical of the three major underground military organizations: the first, and largest, was the Haganah (the “official” group of the yishuv, ultimately under Ben-Gurion’s control), the second largest was the Irgun (or Eztel) under Menachem Begin, and by far the smallest was the Lehi.

The Haganah, determined not to fight the British as long as the British were fighting Germany, responded to Arab attacks, but did not harm British soldiers. The Irgun, determined to get the British out, did attack British personnel, but only soldiers (civilians were at times killed, such as in the famous King David Hotel building bombing, but not intentionally), while the Lehi believed that any ruler over the land of Israel was illegitimate, and that they needed to fight the British at all costs, even at the cost of civilian life (a policy that some argue the Lehi eventually changed1).

While Ben-Gurion was willing to marginally cooperate with the British, Stern was ironically willing to cooperate with the Germans. In fact, as he saw it, the Germans and the yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine) shared a common goal. The Germans wanted the Jews out of the Europe, and the yishuv wanted those Jews to come to Palestine. Perhaps a deal could be worked out, he hoped. No such deal ever came to be.

Ironically, Haim Arlosoroff’s deal with the Germans, called the Transfer Plan, did enable German Jews and their money to get to Palestine, though Arlosoroff (who was a leader of the left, associated with Ben-Gurion’s leadership of the yishuv, and whom we wrote about in this column) paid for that plan with his life when he was assassinated on the Tel Aviv beach in 1933).

Stern’s plan never reached fruition; he was killed by the British before Jews could get to him.

Stern was buried in a small cemetery in Nachalat Yitzchak, in what is today Givatayim (more or less across the Ayalon highway from the Azrielli Center in Tel Aviv). It was a tiny funeral, attended only by close family and many British police and spies, who were hoping that some of Stern’s men might show up to pay last respects to their commander. But the Lehi men were not stupid and did not show; after the British had left Palestine, they came in droves.

What is interesting—as reported by those who attended this year’s commemoration of his death a few weeks ago (the date on the Hebrew calendar)—is that there were still a few of those men, now in wheelchairs, who came to pay tribute to “Yair,” but many younger people, as well. Interestingly, Stern’s popularity seems to be growing among the youth.

There are multiple reasons for that. An indirect one is that the “ban” on giving credit to members of the non-Haganah underground came to an end with Menachem Begin’s election in 1977. Under Ben-Gurion, and to a degree even under the Labor PM’s who followed him, if you had been a member of the Irgun or the Lehi, you were a persona non grata. Government jobs were out of reach. Appointments at the university were difficult to come by. If you had a business, good luck trying to land a contract with a government office. Ben-Gurion considered Stern, Begin (and Yitzchak Shamir, who was one of the three men who split control of the Lehi after Stern’s murder) traitors. They, their biological families and their “fighting families” (as those people’s children and grandchildren refer to them to this very day) were “out.”

Even Jabotinsky, the father of Revisionist Zionism, who died in New York in 1940, was not reinterred in Israel (though in his will he asked to be) until Ben-Gurion was out of office and had been replaced by Levi Eshkol. It was Begin, Jabotinsky’s disciple, who had always wanted to do right by his teacher, but knew it was hopeless with Ben-Gurion. When Eshkol took office Begin sensed opportunity, and Jabotinsky’s remains were brought to Israel. (In the photograph below, Begin is the pallbearer at the front, to our right.)

With Begin’s rise to power, the entire attitude to the underground changed. Begin believed, as do many historians today (including Bruce Hoffman, whose book, Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel, 1917-1947, takes its title from an Avraham Stern poem), that the Irgun (and Lehi, to a lesser extent) were responsible for getting the British to leave. Far from traitors, they had helped give rise to the State of Israel. It was time to give them their due.

Note, for example, this stamp that was issued in Avraham Stern’s memory. Look closely at the date. 1978 (see lower left hand corner)—a year after Begin came to power.

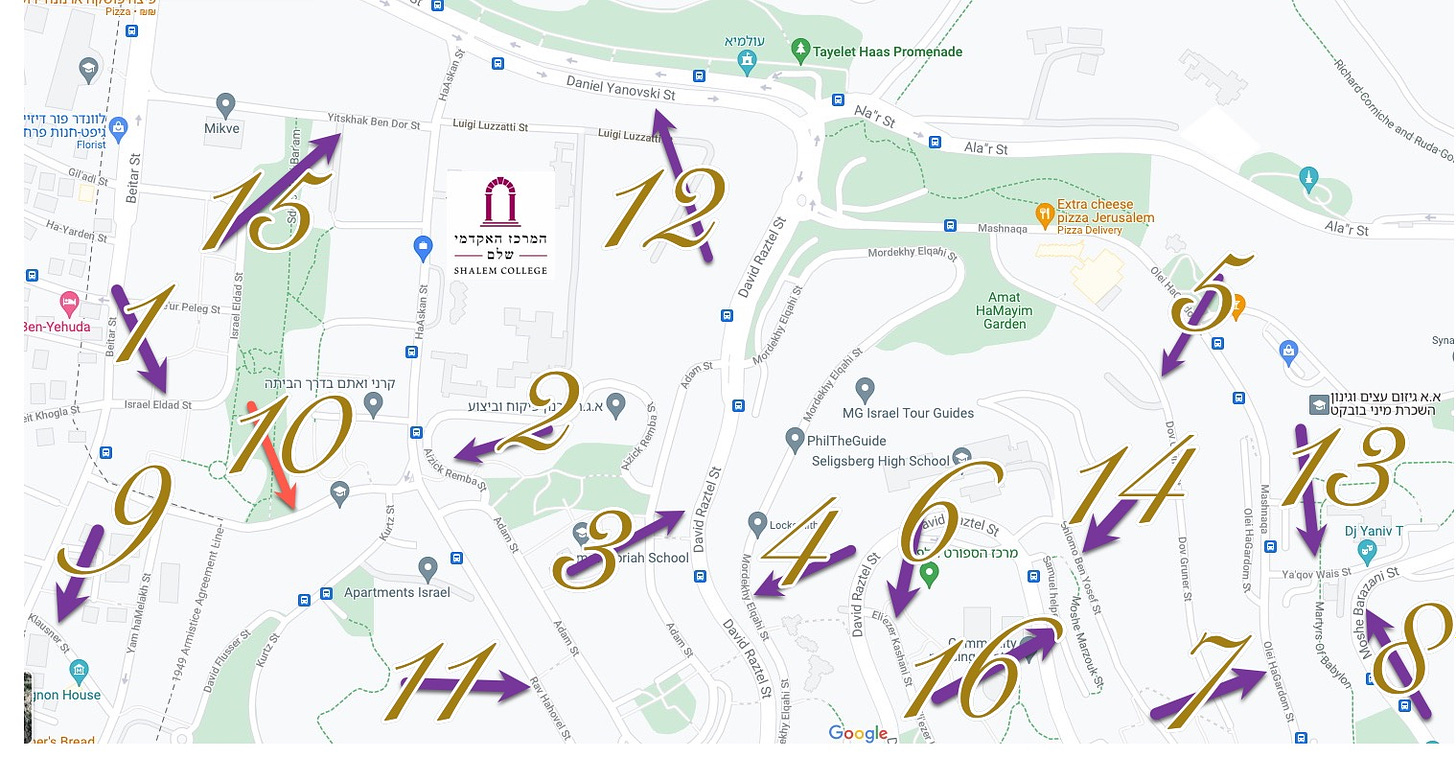

Or take a look at this map of Jerusalem’s “Arnona” neighborhood, which has existed since the early part of the 20th century but which was completely replanned and rebuilt in the 1980’s and onwards—after Begin (and following him, Shamir) took office. (There are an infinite numbers of neighborhoods that have “themes” like this—this one happens to be the neighborhood of Shalem College so I see it every day, but more importantly for this discussion, it’s one that reflects the changed attitudes of post-Labor governments.) Note the names of the streets and who they’re named after (if you want to pull up the unadulterated map on your own screen, use this link):

[1] Israel Eldad: Member of the Lehi. He was arrested in 1944 and freed in an operation by the Lehi. He wrote for the Lehi’s daily paper, HaMivrak. Died on January 22, 1996.

[2] Isaac Remba: Journalist and editor of the newspapers Hamashkif and Herut (Begin’s party newspaper). He died in 1969 of a heart attack.

[3] David Raziel: One of the first members of the Irgun. Previously a member of the Haganah. On May 17, 1941, he was sent to Iraq on behalf of the British Army Intelligence. On May 20 he was killed in Iraq by a German bomb. Begin assumed command of the Irgun after him.

[4] Mordechai Alkahi: Member of the Irgun. He was hung in the Akko prison on April 16, 1947.

[5] Dov Gruner: Member of the Irgun. He was hung in the Akko prison on April 16, 1947.

[6] Eliezer Kashani: Member of the Irgun. He was hung in the Akko prison on April 16, 1947. He was the last to be hung.

[7] Olei HaGardom Street: refers to the Irgun and Lehi members who were tried in British Mandate courts and sentenced to death in the Akko prison. It means “those who ascended the gallows.”

[8] Moshe Barazani- Moshe was a Kurdish Jew born in Iraq. Member of the Lehi. On April 21, 1947, he committed suicide with a hand grenade before his scheduled execution, along with fellow Lehi member, Meir Feinstein. Menachem Begin asked to be buried next to him.

[9] Joseph Klausner: Was a professor of Hebrew literature. He was a candidate for president in the first Israeli presidential elections in 1949. He lost to Chaim Weizmann. He died on October 27, 1958.

[10] Eliyahu Lenkin: Member of the Irgun. Commanded the Altalena ship. He died on August 10, 1994. (Arrow in red, as the street name doesn’t appear on this Google map; go to the link and zoom in and you’ll see the name.)

[11] Rav Hahovel: Translates to “captain of the ship.” See Lenkin, #10, above.

[12] Daniel Yanovski: Was a commander in the Irgun. Was kidnapped by the Haganah.

[13] Ya’qov Wais/ Yaakov Weiss: Member of the Irgun. On July 29, 1947, he was executed for his role in the Akko prison break.

[14] Shlomo Ben-Yosef: Member of the Irgun. He was hung in the Akko prison on June 29, 1938. He was the first Jew executed by the British.

[15] Yitskhak Ben Dor: A journalist and member of the “Davar” editorial board. Died June 9, 1948.

It’s quite a message for street names to make. Imagine growing up on “Those Who Ascended the Gallows Street,” as many kids do. The name of your street could do a lot to shape your commitments.

In some measure then, Stern’s revival is part of a larger revival of the fighters of the underground, some of whom, like Begin and Shamir, became Prime Ministers, and others of whom, like Stern and many of those seen on this map, died long before their time.

But that’s only part of the story. The other part has to do with the fact that Stern was not only a warrior, but a poet, too. He’s often said to be a poet of eros, but of eros not for women, but for the Land of Israel. In that regard, Stern, who is gone eighty years now, had an instinct for what contemporary young Israelis today need, and what they’re searching for.

We continue with that in the coming section.

It is not only Avraham Stern’s status as a warrior that has drawn people back to interest in “Yair”; Israel has had warriors aplenty. The real key to his appeal among young Israelis is that eros, that love of the land of Israel, a love that he felt had to be pure. Wanting to establish a Jewish state so that there would be a place for Jews to escape the anti-Semitism of Europe, he believed, was not a sufficiently pure reason to return to the Land of Israel. In that regard, he opposed Herzl’s Zionism, which was almost entirely derived of the Europeans’ “Jewish Question.”

Herzl was wrong, Stern said. Jews needed the Land of Israel the way we need our lovers—not as a place of refuge (though love is to be sure a refuge of sorts), but because we love them simply because they are. Simply because without them, we are not whole. Jews, the Jewish people, needed the land of Israel because without it, we are not whole.

That “Sternian” eros comes through in much of his poetry, of which we’ll look at only one very short example. The poem reads as follows:

You are betrothed to me, my homeland According to all the laws of Moses and Israel… And with my death I will bury my head in your lap And you will live forever in my blood.

The poem is obviously a simple but stunning play on the phrase from the traditional Jewish wedding, in which the groom says to the bride as he places a ring on her finger, “You are betrothed to me according to the laws of Moses and Israel.”

Not a single one of Stern’s readers, religious or secular, young or old, Hebrew speaker or not, could have failed to appreciate the play on words, on ritual, on love. No one could have missed his point: the way that you love that woman under the wedding canopy, the way that you cannot imagine a life without her, the way that you have unlimited hopes and prayers for what you might create and build together—that is how we are supposed to feel about this place.

There was an era in which early Zionists across the spectrum spoke that way. A. D. Gordon (who died a century ago this month (February 22) and who is newly popular among Israeli youth thanks in no small part to the lifelong work of Eliezer Schweid), believed that it was getting the dirt of the Land of Israel under one’s fingernails, working the earth of Israel with one’s raw hands, that was the key to the spiritual renewal of the Jewish people. There were those who saw living on the land as the continuation of the biblical story, which it in some ways unquestionably is. And there were those who loved the land because it was an integral part of the Jewish soul.

Think wedding. Think the power of eros. Think the dizzying effects of love. Think those things, said Stern, and you begin to understand how Jews need to think about this land of ours.

To some, it may sound kitschy, but to many young Israelis, it’s precisely what they’re searching for. Their great-grandparents and grandparents built villages and plowed fields, but their parents raised them in comfortable homes to which they returned after a day of work in Tel Aviv towers made of steel and glass. “What’s the point?”, a young generation is asking. They’re providing all sorts of answers, but the power of eros is speaking to many.

It’s a foreign way of thinking about this place to many who are used to thinking of it as a potential refuge or a huge civil rights project. But neither refuge (to which Israelis at least resonate somewhat) nor Israel as a civil rights project (to which they do not resonate at all) will get Israel’s youngest and best to stay here, to keep building, to keep dreaming.

What will get them to remain is love for the sake of love, commitment for the sake of commitment, land for the filling of our soul, eros—because nothing in life is more powerful.

Which is yet an important reminder that on that day eighty years ago this week, British policemen and their bullets could, indeed, kill Avraham Stern. What they could not kill, and what burns now perhaps brighter than ever, is the flame of love that his poetry helped kindle.

To most of us today, it seems patently obvious that there was something fundamentally obscene about the United States (among other countries) participating in the Berlin Olympics of 1936. The world knew of the horrors that were beginning to unfold (the mass killing of Jews hadn't yet started), but chose to turn a blind eye. We know where that got us.

So why are the United States (and Israel, for that matter), represented at the Chinese Olympics? Is there a parallel between the two Olympics? How should we think about this? About America's obligations, and lessons learned, or not? About Israel's obligations?

In a recent article entitled "Israel 'bombs Auschwitz'", Rafael Medoff, the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, reflected on how Israel's continued strikes on Iran in Syrian territory must be seen in the light of Auschwitz. We reached out to Dr. Medoff for a conversation about that, and about much more--as he is one of the most productive scholars writing about the refusal of the Roosevelt administration to bomb Auschwitz and the role that American Jewish groups played (or did not play) in trying to change the administration's position. It was a far-reaching conversation, which left me thinking about many things... and I hope it will do the same for you.

Here's an excerpt of our conversation. The full podcast will be released on Thursday, as usual, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

See Yair Sheleg, “The Second Lehi: Ideological Heterogeneity alongside a War of Extermination against the British Invader” [Hebrew only], in Makor Rishon, Feb. 1 2022), online at https://www.makorrishon.co.il/opinion/451899/.