One week from tomorrow, Israelis will head to the polls for the fifth time in about two and a half years. Why Israel ends up going to the polls so often, and how this rate makes Israel one of the least stable governments in the world, are subjects for a different conversation.

For now, as we are in the final days of October, we turn to a specific disappointment of these upcoming elections, no matter what the result.

This Haaretz headline sums it up: it is expected that Israeli Arabs will vote in historically low numbers next week.

On the surface, that makes absolutely no sense. After all, given that Israeli Arabs represent 20% of Israel’s population, they could easily wield substantial political clout if they voted. And don’t forget that the Bennet / Lapid government just about to end is the first in which an Israeli Arab party was a member of the coalition. That, too, might have led us to expect that Israeli Arabs would feel more invested in the system.

But they don’t—which is hugely helpful to the Likud and Netanyahu. As Yair Lapid is doing all he can (which is not very much) to encourage Arabs to vote, Netanyahu & Co are hoping (and some say doing even more than hoping) that the Arab turnout will be low.

How are we to explain this expected low Arab turnout at the polls? What does this likely scenario say about the way Israeli Arabs see themselves in this society? What does it suggest about the future?

To address those questions, on Wednesday we will post a podcast conversation with Mohammad Darawshe, one of Israel’s most important Arab public intellectuals.

A very brief excerpt of Darawshe’s comments, a painful one to hear and to absorb, is included here, in the link above. The incident to which he is referring in this section is known as Kafr Kassem, more on which below.

To understand Darawshe’s explanation of the expected low voter turnout, we need first to know something about two historical events (both of which took place in the month of October) which loom largely and painfully for Israeli Arabs, but which are not well-known outside of Israel.

The first of these two events took place on October 29, 1956.

Just as Israel was preparing to launch the war that would become known as the Sinai Campaign, tragedy struck the home front. Arab Israelis had then been living under military rule for eight years, since 1948, and levels of distrust still ran high.

In preparation for the coming battle with Egypt, Israel was worried now only about the southern border, but about possible reactions among Israeli Arabs, too. So the government issued a five P.M. curfew on all the Arab villages in the “Little Triangle” that abutted the Jordanian border, including a village by the name of Kafr Kassem.

News of the curfew was publicized just minutes shy of five o’clock, and most of the laborers did not receive the notice in time. Most workers who encountered army units after the curfew were allowed to pass without incident. But when one group of fifty laborers from Kafr Kassem, returning home after work beyond the five P.M. newly imposed curfew, encountered an IDF patrol, the Israeli soldiers shot and killed forty-nine people from the town—including many women and children. It was the largest massacre of Arabs since the founding of the state. According to some of the soldiers and other experts, they had been ordered to shoot to kill, even though it was obvious that the laborers, just returning from the fields, posed no threat.

Ben-Gurion called the incident a “dreadful atrocity,” and in years to come, numerous Israeli officials expressed profound remorse for the massacre. But Israel’s reaction was more complex. Though several officers were arrested and later convicted, all were released from jail shortly thereafter. One commanding officer was fined ten cents [perutot in Hebrew], a move which spoke volumes.

In October 2006, Israel’s then minister of education, Yuli Tamir, instructed Israeli schools to commemorate the Kafr Kassem massacre and to reflect upon the need to disobey patently immoral orders. In December 2007, Israel’s president, Shimon Peres, attended a reception in Kafr Kassem during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha, and asked for the community’s forgiveness. “A terrible event happened here in the past, and we are deeply sorry for it,” he said. In October 2014, a full fifty-eight years after the horror, Reuven Rivlin, Israel’s tenth president, became the first to attend the annual memorial ceremony at Kafr Kassem.

The Kafr Kassem tragedy had long-term legal implications for Israeli society. The trial was the first time that the Israeli judiciary discussed whether and when Israeli security personnel were obliged to disobey even a direct order that was manifestly illegal. Judge Benjamin Halevy (who heard the case as a sole judge) wrote that “the distinguishing mark of a manifestly illegal order is that above such an order should fly, like a black flag, a warning saying: ‘Prohibited!’” In years to come, the phrase “a manifestly illegal order,” a direct quote from Halevy’s decision, would become ubiquitous in Israeli discussions of the morality of the conduct of war.

To what extent has Israel internalized the horrific lessons of that terrible day? Among jurists, academics and others, the event is well known and much-discussed. But I’m willing to bet that if one polled the cars driving by the “Qesem” interchange on Israel’s Highway 6 (where it meets Highway 5) and asked them what the name referred to, the vast majority of drivers would likely have no idea.

Decades after the events of October 1956 and after Israel had signed the Oslo Accords which then collapsed, Israel found itself mired in the just-beginning Second Intifada. This intifada proved far more lethal than the First Intifada due to the Palestinian Authority’s security forces’ use of weapons and suicide bombers. The conflict spread to Israel’s Arabs as well, particularly in the heavily Arab-populated Galilee. In events that were eerily similar to the rioting of May 2021, about which we wrote then, some Arab Israelis attacked Jewish property, vehicles, settlements, and institutions. Israeli Jews began rioting against mosques, Arab-owned businesses, and Arab residents in mixed cities.

In what became known as the October 2000 Events or the October Ignition, Israeli police and the Arab rioters clashed after a demonstration escalated into violence. Arabs threw rocks and firebombs, launched ball bearings in slingshots, and, in a few cases, fired live rounds. In response, the police fired live ammunition, and in the course of a few days in October, thirteen Israeli Arabs were shot and killed by Israeli security forces. The Or Commission, which would later investigate the incidents, found that the police were unprepared for the violence and in some cases had overreacted (several of the Arabs killed had been shot in the back).

October 2000 was unlike Kafr Kassem in 1956, since in the later case, Arabs had without question resorted to violence. But in the minds of Israeli Arabs, the incidents were related. Like the 1956 Kafr Kassem massacre and the events of Land Day in 1976 (which we will discuss in a different column), the October 2000 killings reinforced their sense that they were perpetually second-class citizens whose lives were valued differently from those of Jews. As they noted repeatedly, when Haredim burned tires on roads in protest and used low-level violence, the security forces never opened fire on them.

In the hopes of understanding better how these events of October 1956 and October 2000 continue to reverberate in the mindset of Israel’s Arab population, I reached out to political leaders of Kafr Kassem, hoping that my introduction by leading Israeli Arabs might open doors, but interestingly, no one responded. It was then that I turned to Mohammad Darawshe, for whom I have enormous admiration, and asked him to explain to me how this all plays out in the mindset of today’s Israeli Arabs.

Our conversation was, for me, illuminating but painful. Given that our discussion presupposed some familiarity with October 1956 and October 2000, this column is a bit of a primer. On Wednesday, we will post our conversation. Whether you lean right or left, tend religious or secular, Jewish or not, I suspect you will find yourself thinking about what Darawshe has to say for a very long time.

And come November 1, no matter what the election results, you’ll have a much better understanding of why 20% of Israel’s population, who seemingly had the most to gain from voting, likely decided to stay away.

More on Wednesday.

Wondering how it could possibly be that Itamar Ben-Gvir is getting such traction? Have thousands of Israelis lost their minds or become racists? Here’s a fascinating article about Ben-Gvir by Armin Rosen in Tablet Magazine — you might not love Ben-Gvir when you’re done, but you’ll certainly see how complex the real story is.

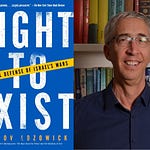

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.