The restaurants and cafes were full on Sunday morning. During the night, we’d been hunkered down while Iranian weaponry exploded in the air above our homes, we then got very little sleep, and by morning, everything was back to normal. People were out for coffee, a danish, heading off to work (though schools were still closed). Frankly, the “morning after” was almost as extraordinary as the repelling of the attack.

Today’s podcast is a conversation with one of Israel’s most courageous and admired religious figures, on a series of subjects that do not generate humor. We nonetheless begin with a few more of the reactions on Israeli social media to (a) those hours we spent waiting for the drones to hit and (b) the question of whether Israel should retaliate and (c) which soldiers “get to” or “have to” go home for Pesach, simply as more indications of how Israeli humor in trying times is but one of many indications of our striking resilience.

Then we get to the serious stuff.

The hours between the launch of the drones and the cruise missiles were a bit otherworldly. On TV, they were tracking the progress of the weapons and you could figure out more or less when they were going to hit. But there were still hours to go. The waiting was driving many people crazy:

The woman who posted the above wrote (during those hours of waiting for the hit), “I feel like I’m waiting for the repair guy to come, between Friday and Sunday.”

Or try this one on for size. Matan Peretz, a wildly popular Israel standup comedian, posted the following on Facebook, both as comedy and as an ad for his upcoming performance.

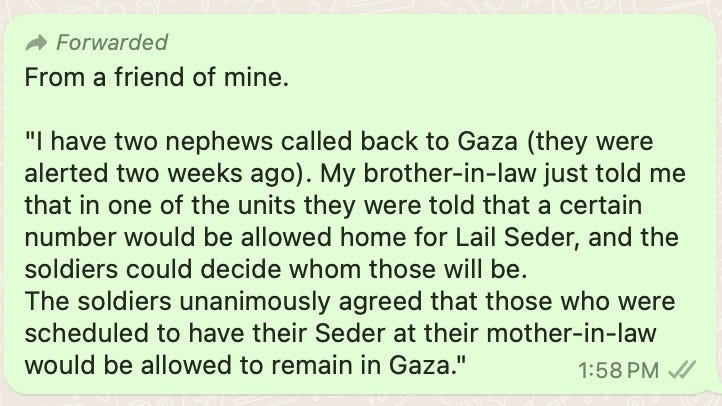

Or, to bring us closer to the Seder and not the Iran issue, the following also elicited more than a few chuckles as it mades its way around, in both Hebrew and English, on Israeli social media:

Now for the serious stuff—like the future of the Jewish state.

The spread above appeared in the Makor Rishon newspaper a couple of months ago. Pictured are Rabbi David Stav, on the left, and journalist Orit Navon. It was a fascinating conversation, in which a woman who grew up religious but is no longer observant (and no longer has great warmth for much of her formerly religious world) had an open and honest conversation with a rabbi who was sensitive, but unapologetic about the world he represents. It was a masterpiece of openness and dialogue for both.

Rabbi David Stav is to many people one of the most venerated religious figures in Israel. He is the chief rabbi of the city of Shoham and the founder of Tzohar, an organization that works to foster vibrant and inspiring Jewish identity in Israel.

Once a candidate for the Chief Rabbinate, he exerts more influence than almost anyone else calling for a more embracing, inclusive, moral and Zionist Orthodox Judaism.

Rabbi Stav and Orit Navon covered an array of subjects, including the subtle halakhic changes that were filtering through the religious community when Gaza was still packed with Israeli soldiers. What should religious families do when the husband gets some time “out” on Shabbat, but not enough to get home and back? What should couples do when the husband’s time “out” doesn’t work with the wife’s cycle and the laws of family purity?

There have been some surprisingly lenient rulings issued on these matters—by Orthodox rabbis—in recent months. Rabbi Stav is not party to most of them, but neither is he critical of them. The openness and warmth of the conversation, in which Navon shared her frustration that he wasn’t more lenient, was deeply moving.

Shortly after I read that article and thought that it would make for a fascinating post, Rabbi Stav’s office contacted us and wondered whether we might be open to hosting him for a conversation about the Haredi draft issue, which then seemed about to explode. “Open?” We were deeply, deeply honored, and recorded today’s conversation.

Since we recorded, Iran has temporarily moved the spotlight away from the Haredi draft issue, but that issue has not gone away. It will raise its head again, and when it does, we will see that most Israelis have had it with the present arrangement. So, too, has Rabbi Stav, who explains in the discussion why in his view, the present arrangement is one in which Haredim steal from the state in four different ways.

The conversation was not only about Haredim, but our internal divides. Like many people here, Rabbi Stav is not worried about our external enemies. They are tough, but we are tougher, and he has no doubt we will defeat them. What will be inside this country, though, once those battles are behind us, is what concerns him.

The link at the top of this posting will take you to the full recording of our conversation; below you will find a transcript for those who prefer to read, available specially for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

As we’ve mentioned for the past several weeks, we will be taking Passover off as people will be vacationing and traveling.

While we are taking off for Passover, though, there will still be 133 hostages stuck in hell, whose families do not get a moment of reprieve from the anguish, heartache and fear they’ve been living with for six months. Pray for them. Pray that the captives reutrn home soon, so that they and their families can begin to heal.

Rabbi David Stav, one of the leading religious personalities in Israel, is the co-founder and chairman of the Tzohar Rabbinical Organization, a rabbinical organization which aims to provide religious services to and create dialog with the broader Israeli population. He also serves as the rabbi of the city of Shoham. Previously, he served as the rabbi of the religious film school, Maale, and was one of the founding heads Yeshivat Hesder Petach Tikva. He's the author of “Bein Ha-Zemanim”, a book about culture and recreation in Jewish thought and law.

He is one of Israel's most venerated and visible rabbinic figures, who has taken on very, very brave positions about a whole series of issues, including the question of whether or not two chief rabbis are actually necessary, how to deal with the agunah problem, the problem of women who are not able to get divorces by increasing the use of prenuptial agreements and a whole array of other issues.

We spoke to Rabbi Stav originally in our podcast in February of 2023, a bit over a year ago, when the judicial reform or judicial revolution issue was just beginning to take on tremendous amount of importance. We spoke about the very, very deep nature of the divide in Israeli society.

Now that Israel is at war with Gaza, we got together with Rabbi Stave again to ask, is our problem, Gaza? Is our problem the region? Is our problem still internal divisions in Israeli society? How can we, if at all, address the issue of the ultra-Orthodox draft? And much more. Very, very deeply grateful to Rabbi Stav for taking the time out of an extraordinarily busy schedule to meet with us once again and to allow us to hear his thoughts.

So, Rabbi Stav, first of all, thank you very much for joining us once again. The last time that you and I had occasion to speak, the last time that I had the great honor of speaking with you on this podcast, we were in the middle of the judicial crisis. Some people call it the judicial revolution, the judicial overhaul, the judicial reform, depending on how you saw it, depends on what you call it. And we were both very, very worried about the internal division in the Jewish people, and we were very worried about where that might lead us.

Neither of us could have possibly imagined that we would find ourselves here now, almost yearning for the good old days when democracy was our only problem. We're going to come back to that because, of course, as you and I pointed out to each other as we were walking over to the office, that the problem has not really changed all that much. It's still a problem of division in the Jewish people, and we'll come back to that.

But I wanted to reach out to you and hear your thoughts, most importantly and most immediately, about perhaps one of the most immediate crises facing the government and the state of Israel, which is the draft of the Haredim, the ultra-Orthodox. And you are a person who is very much part of the religious community. Candidate once for the chief rabbi, to be the chief rabbi of Israel, a person deeply devoted to tradition. We can't exaggerate that enough. And yet, I suspect you have very strong feelings about how the ultra-Orthodox community needs to position itself in response to the new calls for them to get drafted.

So, I just want to hear, first of all, what you would say to Jewish people around the world who are listening to us, some in Israel, but mostly abroad. How do we need to understand this crisis? Who needs to do what to enable this crisis to pass and for us to move forward?

Well, usually, I introduce myself as the Chief Rabbi of Shoham and the chairman of the Tzohar Rabbinic Organization. But for that interview, I think I should focus on another title that I'm a proud father of eight boys and sons-in-law, eight sons and sons-in-law that were drafted in the last war. Actually, one of my sons is now drafted again for the reserves in the north, which is getting hotter and hotter from day to day.

And as a father of eight boys and sons-in-law that sees how there's a whole group of people, more than a million people, that none of the children, almost none of the children is serving in the army. I think it's something which is not moral. It's not Jewish. It's against the laws of the Torus, against the tradition of our people. And I think that the leadership of the ultra-Orthodox society that does not agree to any kind of service in the army or a national service is sinning to hashem, to God, is sinning to itself in any criteria of moral values and halacha.

But after saying this and just expressing my frustration from the fact that none of the leaders of the Haredi society had the courage to come out and to say enough is enough, and also none of the political leaders in the government has the courage to say enough is enough. We have to realize that you cannot solve this problem without understanding the roots or the concerns of the Haredi society from the service in the army.

Before discussing all the issues, let's clarify. We are talking about facts, and we are talking about arguments that many of them are not representing the truth. They are false arguments. For instance, the arguments that we want to release only the Yeshiva boys who dedicate and devote themselves for Torah studies. If that was the story, we could have solved it easily. The problem is not the 5,000 or 6,000 people that really dedicate their lives for Torah. That's not the story. Most of the Haredi boys do not learn Torah for 10, for 12 or 20 years. They do not do that. They are registered in the Yeshivot in order not to go to the army, but they do not learn Torah. They hang out, they do this, they work.

So, they steal the government, or they steal the state twice and sometimes four times. A) they don't go to the army. That's still number one. Still, number two, they take money from the government as pretending that they are learning Torah. Number three, they are working without permission because they are not allowed to work. So, they cannot report that they are working. So, they don't pay income tax. They don't pay the municipality taxes because they don't have income, which is the fourth line. And this is something that Israeli society couldn't suffer anymore, couldn't bear anymore. And I think this has to come to an end.

Having said that, we have to understand that the is a real concern of the Haredi society, which is not about the Torah studies. It's about the fear that once the Yeshiva boys that will have to go to the army, they will be influenced to be secular. And that's the real fear and the real concern of the Haredi society. And this has to get an answer. And so far, there are debates whether the army is prepared to give them all the answers and I guess the truth is somewhere in the middle. Some get the right responses from the army, and some cases, they do not.

What would be the right responses from the army? What should the army in an ideal world, I mean, the army is an army. It's not a big yeshiva, it's not a Torah study institution. It has a very big job, so it's limited, perhaps, in some of the things that it can do. But what should the army, in a realistic way, do to enable it to be possible for these Haredi young men to serve and somehow minimize the worries of their rabbinic leadership?

I think sometimes I hear stories that the army is doing much more than it's needed. I don't think the army has to provide a mikveh, a place to go to the water every morning before davening. I don't think that is something that the army has to provide to the yeshiva boys. On the other hand, I think the army has to provide the proper food and the proper environment for the Haredi soldiers, meaning that they will not have to serve together with girls, that they will not have commanders that are girls, et cetera, et cetera. That Haredi boys that are used to grow up in a separated education will continue to live their lives in the army in the same lifestyle that they were used to, that they will get only religious commanders, not people, you know the language is sometimes not the proper language, and they should get commanders that are talking in a proper and a polite way that fits to the Haredi lifestyle. That's one thing that should be done.

Do you think they should serve with only Haredi men?

Haredi or dati leumi or modern Orthodox people, but without secular boys and girls.

No, leave girls, leave women outside of it for a second. If they're in a tank unit, you think that they should be in a unit where there are only religious soldiers?

If we want to convince those who are ready to be convinced, I'll talk about it in a minute. If we want to convince those who are ready to be convinced, that's a demand that I could live with. But to be honest, I don't think it's going to happen. A, because I don't see the army is prepared to do that, and B, I don't see the Haredi politicians agree to that. Therefore, I think that that's what I came to a thought and to a conclusion. We wrote an article, me and Uri Zaki. Uri Zaki is the chairman of Meretz, which is a left-left wing party. And he is the chairman of the secretaries there or whatever, one of the politicians in Meretz. And we wrote a paper that the idea says you know what? You don't want to go to the army. Okay, don't go to the army. But at least stop stealing from us. Please declare that the reason why you don't go to the army is because of religious reasons. And by the way, there is a law that allows girls today not to go to the army because of religious reasons. And that's actually the real reason why you don't want to go to the army. Don't go to the army from age 18, not from age 26, from age 18. So at least the government will not have to support yeshivot in billions of shekalim because there will be less yeshivot boys, because those who do not want to learn will not need to be registered in Yeshiva in order to learn.

Will they do sherut leumi, National Service?

Wait a minute, before sherut leumi.

Okay.

First of all, you can go to work. You don't have to work in black. You can work and report that you are working. That’s A. B, I guess most of the Haredi people want to earn distinguished salaries. They don't want to live poor life. Those who want to learn Torah, they're very easy to live in a lower level of lifestyle. But those who go to work want to live good life. So, they will need to be reeducated. I mean, not reeducated in values, but to educate, to teach, to learn English, to learn mathematics, to learn other professions that are needed to know in this modern world, they will need to complete the studies. Somebody will have to pay for that.

What we suggested is that the government will give the vouchers for studies, for high studies, for elementary studies, whatever is needed for these boys in condition of a national service, in condition of service in the army. And certainly, when we say national service, in the religious communities, you can't imagine how many needs the religious community needs. I mean, all the Haredi neighborhoods, there's nobody to protect them. Today, if a terrorist comes, as we have just seen a year ago in Ramot or in Neve Yaakov, where a bomber, Hamas, or somebody came and started to shoot, and there was nobody with a gun because all the people around them were yeshiva boys. None of them knew how to shoot.

So, you can do things that will help your community and will not force you to engage with secular people or with girls or with the secular society that the Haredi leadership is afraid of. I don't want to justify them if they are right or wrong. That's their concern, and we have to take it in consideration.

Now, what the government is doing, the current government and the previous government, the current policy is to encourage yeshiva boys not to go to the army and not to go to work. Because today, in order to convince a yeshiva boy that does not work and does not learn to go to work, it doesn't pay to go to work because now he doesn't have to pay taxes of municipality. he doesn't have to pay the social security, health care, all these issues, he gets for free. Why would he go to work and would earn five or six or 8,000 shekels when he gets this today by not working and by not learning? So, the government today is encouraging him not to go to work and not to go to learn. Therefore, the numbers keep on growing because there is no incentive to go to work, no incentive to go to the army.

I don't want to force nobody to do something which is against his ideology. As I said in the beginning of my words, I think it's a big flag, a big moral flag on the Haredi community that as the Prophet Devora was saying, lama yeshavta bein hamishpatim, she blames the tribes of Reuben and Gad. How come you sat with your ship, and you did not join the war? How come you sat in your neighborhoods, and you did not join the war? You did not participate there? It's a moral blame on them. But I'm not going to judge them now. I'm now going, I want to solve the problem. If you don't help, if you don't carry responsibility on your shoulder with the army, please do it in the economy. But you don't pay taxes, you don't go to the army, and you want the secular and the dati leumi tribe to support you. That's unhealthy.

You said before that you're not entirely sure that the army can or would do everything that it maybe should do, but it doesn't really matter because you don't really think that the Haredi leadership is interested in reaching a compromise because they have a good deal going for these young people. I mean, as you point out, if you can earn the same salary by not working that you would earn working, why would you? I mean, there are a lot of reasons that you might want to work, and you should work, but that's another issue altogether. You can understand from their short-term perspective why they would think that not working is a better deal.

We're in a crisis in this country. First of all, I think, as you very well know, when we used to talk about Haredi draft, it was an issue of fairness. It was shiviyon b’netel [equal burden]. It was everybody carrying the weight equally. And I think the discourse in Israel has changed, which is now that it's not only an issue of fairness, it's an issue of need. We just need more soldiers. At least that's what the IDF is saying. And they're adding, as you know, because you have boys in the reserves, my son is in the reserves, they're multiplying the amount of reserve time, and they're increasing the maximum age. And in some cases, it's going to be five X. It's going to go up five times the amount of reserve duty, which is just insane. So, it used to be a matter of fairness.

Now it's a matter of need. We're at war. We might be at war for a very long time. So, Rav Stav, how do you see this playing out? The army can do certain things. The government is in cahoots with the Haredim. The Haredim leadership has no incentive to change. Where are we headed?

Well, first of all, you're 100% right in the way you describe it. Before I try to give a kind of answer to your question, I want to refer to this from a religious point of view. The Judaism is paying a very heavy price for them because people don't distinguish between different types of frum people and eventually they say, well, these frum people that seem to be very serious in their frumkeit, in their religion. They must probably believe that they represent the Torah. If that's Torah, we don't want to have anything with Torah, what we call a violation of the name of God. And that's a violation of the Torah. So, we have to understand that it will require us to pay a Jewish price, and we are paying this Jewish price with cash.

We're also paying it with lost Jewish souls, Jewish-Israelis who might otherwise be very open to seeing the richness of their tradition, but say, if that's what it is, I don't want any part of it.

Exactly. That's the argument. Now, the problem is, I cannot blame only one side. The problem is our politicians as well, our leadership. And maybe it's the political system in Israel. Suppose we had the American system by us. A President that had to be elected and would say, I will continue that situation with the Haredi parties, would have not been elected today. There's no doubt about it. The problem is that we need a coalition. And today, each one of the leaders of the secular parties needs the Haredi parties for its coalition and is ready to pay the highest prices on the expense of his voters, of his constituency that cares about it, but doesn't care enough in order not to vote for that party. And that's actually the price we pay.

You think that's true of Gantz even now?

Until we will be convinced. I'm not convinced yet with the initiatives of Gantz that seem to be more of the same. I don't see him going all the way to a solution that will solve it once and forever because he thinks, I'm not a politician, but from what I read, between the lines, I understand that he wants to have a coalition with him, and he's ready to pay prices for them. Maybe because of the current situation, the notion of our leaders will come to understanding that the society is not ready to accept it anymore, not only because of the need. The need is a very important point. But the price that we paid this year is something that we cannot ignore. I mean, the fact that modern Orthodox part in the war is almost 40 or 50% of the soldiers that were killed during the invasion to Gaza, this is something we cannot continue with in the future. And maybe some politicians I think that we could continue just like in the past. I think this is already gone. We're not there. And the second society feels alike. They feel the same.

And this story is something that is yet too early to evaluate whether the politicians will have to take it into consideration in a level that if somebody will not be determined to say, I'm going to change it, until he will be convinced that he will not be elected as a candidate to be Prime Minister, nothing will be changed. But I get the feeling that today the climate in the street is such that somebody that will not be committed to that will not be able to be the next leader of the state of Israel, and this could change it.

That's actually optimistic. I mean, in the sense that the people might be speaking up and we might finally push a change, which at the end of the day, I also think is good for the Haredim. In other words, for their kids to be hanging out is not good for anybody.

Let me ask you something that's not having anything to do with the army. I heard a fascinating Zoom presentation. It must have been November, December, after the war had started, and there was a lot of discussion of the Haredi draft. And there were two women from the Haredim hachadashim, the new Haredim, most of them young, a little bit more open to the Western world, very much committed to the Haredi world, but open more. They were very interesting, and they were really very thoughtful, I thought. And one of them made the interesting point that part of what this issue is, is in addition to the Yeshiva issue, is the whole shiduchim issue, is the whole marriage arrangement issue, and that there's a certain hierarchy, depending on where the young man is learning and where the young woman comes from and so forth. And her argument was, you take people out of the yeshiva system or the Haredi system and put them in a different system from the ages of 18, 19, 20, 21, whatever, you're going to mess up all of the shiduch system and the hierarchy of how matches are made. She was not arguing that the change shouldn't be made. She was simply trying to explain why it's more complicated. Do you agree with that assessment? Is that a big part of this picture, or is that an ex-post facto justification?

No, first of all, I agree with the fact, but it's like to discuss issues of the 6th of October. I mean, they are 100% right. But suppose a change will happen, this will change also the shiduch system. By the way, the shiduch system is not only a shiduch system. It's a whole issue of the schools your kids could be accepted. If your father is working, God forbid, your father is working 6 hours a day, there are certain places that the kid will not be accepted. If your father wears a colored shirt, sometimes it will be a reason for not being accepted. I heard, just like in America, there are places where they check in shiduchim, in the Haredi society today, did the parents go to the rally in Washington, the last rally that took place, that's a reason already not to do the shiduchim because that shows that they are a bit too modern. Or is the tablecloth on Friday night, is it colored or is it white? These are things that I agree that they exist today. But suppose 20, 30, 40% of the boys will go to the army, it will ruin up the entire system of the shiduchim. Just like if 30, 40% will go to work, it will mess up the entire system of shiduchim.

The system will adapt.

Exactly.

Okay. Let's go up from 10,000 feet to 30,000 feet, as they say, and leave the Haredim a little bit on the side. And we'll talk about Eretz Yisrael, and Am Yisrael, and Medinat Yisrael, the land of Israel, the people of Israel, the state of Israel. People say it must be heartbreaking. And I say it's not actually heartbreaking, it's soul-shattering. Our neshamot [souls] have been just exploded, and the pain, and the agony, and the worry, and the number of funerals we've been to, and the number of shivas we've been to, and the worry about our kids who are in army, out of the army, in the army, out of the army, watching what's happened to the hostages, and the suffering there is just so unbelievably horrible. And those stories keep coming. We're just a broken-hearted people. And I sit down on Shabbat, and I get Haaretz and Makor Rishon and the Yedioth Ahronoth and I think it's almost... I shouldn’t be reading the paper on Shabbat…

I want to recommend you… trust me, Danny. I don't read all these papers. I read only Makor Rishon. But I accepted upon myself already a year and a half ago in Yom Kippur, never on Shabbat. It gives me such a relax on Shabbat. Don't deal with these issues on Shabbat. Shabbat should be a small paradise. In paradise, you don't read papers. Trust me, it will make your family life and your own life amazing.

The good news is that I'm usually so far behind on Daf Yomi that I spend most of Shabbat catching up on Daf Yomi so, that I don't have that much time for newspapers. But okay. We're in a broken-hearted situation here. You are really one of the great religious figures in Israel. You're seen by thousands of people as a source of deep devotion to Torat Yisrael, the Torah of Israel, to Am Israel, the people of Israel, and to Medinat Israel. You and I spoke about a year ago or so, I forget the exact date we were talking about how heartbreaking it was to watch this company rip itself to shreds. We're in a different a battle now. First of all, let me ask you this. Is this an existential moment for Israel? Are you worried about the survival of the state of Israel?

No. I'm not worried about the survival of the state of Israel. I'm concerned about the way the Israeli society will look like in the next 20, 30 years. It's a different concern. Bizrat Hashem, we will overcome the current challenge with Hamas in the south and with the Hezbollah in the north.

And Iran to the east.

And Iran to the east. And the Arabs in Judea and Samaria. We have a lot of challenges. I always believed, and I still believe, that our problems do not start and do not end with our external enemies. I really believe that our problems are the internal problems, not the external. I'm not talking from a spiritual point of view that sometimes undermines the reality issues. No, I don't undermine the physical threats of the state of Israel, but I really believe that we have the power to overcome it and to defeat our enemies. One way or another, I'm very sorry about the prices that we pay, and we might pay the prices that we paid, and most probably we will pay in the future. But that's not my deepest concern.

I could tell you that in Tzohar I gathered a few people two days after October 7th, when the war was just in the beginning, and we I heard every day about the sacrifices and the kibbutzim and Be’eri and all the terrible stories that started to show up. And I gathered my people and said, let's prepare ourselves to the day after the war, because now we are in a war and the solidarity is unbelievable. Everybody gives a hand and is ready to help one way or another. All the tribes, more or less, but most of the tribes, at least. But the day after the war, and when I speak about the day after the war, I'm not replacing Biden. I'm not talking about what will be the final solution in Gaza or in Lebanon. That's not my business, although it's important.

The day after the war is how do we return from that war and not coming back to the fights of October 6th? We have to remind ourselves. Two weeks before October 7th, we all celebrated Yom Kippur, and we remember what were the fights around Yom Kippur in Tel Aviv, the disruptions for the tzohar davenings and for other people who were davening. We remember October 7th, Simchat Torah was supposed to be a day where there will be a lot of debates in Tel Aviv about the hakafot, about the dancing will be separated in the public arena, not separated. And all of a sudden somebody told us, well, you put this separation in the wrong place. You should have kept, put your eye in the separation near Gaza and not in the separation in middle of Tel Aviv. That should be a problem. And I think that we are coming back now to the same place. And this is the real concern.

And I'm afraid of two types of people. I'm afraid of the politicians that their political interest is to strengthen the basis, political basis, by increasing hatred to the other side and by explaining us why the other side is dangerous to the state of Israel. So that's politicians. And media, social media, communication, television, whether it's Channel 12 or 13 or 14, doesn't matter, each one from each side, that naturally want to strengthen the extreme voices and to give them the microphone and to give them with the highest volume so that others will be assaulted so, that they will get there are crowds that watch them, so they will benefit financially and maybe politically.

Where the vast majority of the Israeli society is not there, the vast majority of the Israeli society, their hearts is now with the soldiers The heart is now with the common Jewish denominator that exist and has to be strengthened. And they have no voice because the politicians have no interest to raise their voice, and the media has no interest to raise their voice. And that's actually what is missing. By the way, we are working on that very hard in order to develop social media and in general, media that will raise the voice, it's not only of tolerance, a voice of unity, voice of common Jewish denominator that I believe that most of the people share.

But unfortunately, the voice is not heard. Now, I want to add one more thing to that point is October 7th showed us or taught us two lessons, a: the failure of leadership, whether it's in the army, whether it's in politicians, whether it's in the government offices that didn't function, not before the war, not in the beginning of the war. On the other side, it taught us an amazing lesson about the strength of the civil society of the Jewish people. Somebody said to me an idea, and I think it's such a great idea. He said to me, maybe we are the smallest nation in the world, but we are the biggest, largest family in the world.

That’s beautiful.

And it's so true. We discovered our relatives. The Israelis discovered the communities in America, in the communities in America discovered Israel. And all of a sudden, we realized that we are really one big family. And sometimes the teachers or the leaders of the family don't function because maybe they're too old to be in the job or before for whatever reason. And then the family functions. And we showed and we proved ourselves that we are strong. And therefore, I believe that eventually there will be no other choice but the nation, people from the people, will come and will create a leadership that will be able to sustain the solidarity and the spiritual wave that started to arise in this.

We're hearing lots of people come out of Gaza, many of them in mixed tanks. People tell the stories, we were in a tank for 100 days, and it was one religious guy, and one Meretz guy and one this guy and whatever. And we're committed to leaving the toxicity of the old conversation behind. We want to build something new, and they mean it. You can see it. You can hear it in their voices. They really mean it. So, I hear you saying that they may pull it off. There may be enough people who came out of Gaza and who were in the north or whatever who really feel that we to try to restart something. Are you optimistic that a new echelon of political leadership is going to emerge from the veterans of this war?

I believe that there is a potential for that. I'll add one more thing to that. I think that today, from both sides, we understand that most of the issues that politically divided the Israeli society 10 years ago are not relevant anymore. I mean, you could be right, and you could be left, and still none of you will believe that there is a two-stage solution, for instance, with the Palestinians. You have to be very, very left-winger to the 4, 5%, I'm not talking about the ideology. I'm talking about the practice. Nobody thinks that there is a practical solution with the Palestinians within the next 10, 20 years. If that's the case, why should we keep on fighting on this issue if there is no partner.

Today, I think 80% of Israeli society is there. On the other side, 80% of the Israeli society understands that nobody has any intention now Yehuda and Shomron an integral part of Israel and to make a kind of apartheid or whatever with the Palestinians or to throw them out. Nobody thinks about it. And any percent don't think that we are going now to resettle Gaza. Maybe ideologically they would love to do that. But they understand that that's not where the people are.

So, I think that today, to use even the terminology of right and left of October 6th, you seem to be opposite to somebody that came from a different star. We're not there. We have other issues to deal with. I believe that this gives us a huge opportunity of breaking the paradigms. I think that Judaism is an amazing opportunity today because I think more and more Israelis are thirsty to hear Judaism. They do not want to hear Judaism that will coerce them, and they do not want to hear Judaism that is not carrying together with them the responsibility for the state of Israel, whether it's in the economy or in the army. But I believe that we live now in a window of opportunities. We should make all efforts not to miss that.

That is for sure. Look, we're in a difficult period. But to hear someone like you, you've been at the forefront of opening up the flower of the richness of Jewish tradition to Israelis far beyond the religious community. This is what your whole life's work has been about. To hear you being so thoughtful and nuanced about the issue of the Haredim, not to solve it with a sledgehammer, but to try to be more nuanced and to see the opportunities that are deeply, deeply woven into this moment is, I think, really very, very heartening. Also, to hear you say that while this is a crisis moment for Israel, it's not a moment of existential threat, I think it's also something very important for people to hear.

I would like to add one more thing. We are a few days after the Megillah reading. Tzohar had more than 700 places, locations of Megillah readings, but maybe the most exciting one was in Tel Aviv. We read the Megillah, and I spoke before the Megillah reading in front of several thousands. I don't want to say tens of thousands, but at least several thousands of secular Israelis. I dare to say that most of them for the first time heard the Megillah. It was in the Hostages Square. And to see them listening to the Megillah, to see them for the first time in the places where prayers were disturbed a few months ago, before October 7th on Yom Kippur. And by the way, one of my dreams, and we're working on it already now, is to make a public prayer in Yom Kippur, next Yom Kippur, which is already six months, to make a public prayer in Yom Kippur, in all the places that were disturbed last year, together with all the people that disturbed the Daven. And each one will make the mechitza the way he wants. We won't intervene in the way you will daven; in the way I will daven.

Just let us be together and let us feel and express our Jewish identity and our Jewish love to each other. I believe that this will be a tikkun of correction, of correcting, of fixing the huge damage of the self-hatred, of the internal hatred between us, and will lead us to the vision that we will be a source of light for us and for the nations.

If you have that daven in Tel Aviv with all those people, tell me, we'll come.

We will have. Bizrat HaShem.

I mean love our minyan that we go to, but that it would be such a powerful moment. I'll find a place to stay someplace, and we'll come from Yom Kippur to Tel Aviv. It would be, I think, an unbelievable experience.

Look, what you're saying about the Megillah reading, so much of Judaism has taken on a new richness in the last 18 months, even for people for whom it's not normally their thing. On Tisha B'Av, we saw people who are not normally that involved in Tisha B'Av, sitting, and reading Eicha. I mean, we didn't know what was going to be coming, but we knew about Shisha BAv, which was the Knesset vote. You saw people who were totally secular sitting on the sidewalks in Tel Aviv with religious people reading Eicha. You mentioned the Megillah reading in Tel Aviv, here in Jerusalem, as I'm sure you know, not in Hostage Square, but in Hostage Tent, there was also a Megillah reading where they read the whole Megillah in the Eicha trope. They read it to... It was very cognitively dissonant. It was very hard to do, by the way, the person who read it did an amazing job because we were so used to hearing it in one melody to change it entirely is no small accomplishment. But again, it had religious people and secular people, all of them brought together in a moment of pain, but they're brought together by a Jewish moment. And so maybe this really is an opportunity not only for political healing and Haredi healing, but for Judaism.

Just before Purim, we had the Taanit Esther, the fast of Esther.

On Thursday.

On Thursday. The fast of Esther, usually, it's not one of the most important fasts. And yet there were a lot of secular people that fasted on this fast. One of them wrote a post. He fasted, I called it already in the 10th Tevet. I said that the soldiers that are fighting in Gaza do not have to fast. But I urge secular people and regular people that usually do not fast, fast for those who cannot fast. And several secular people said, we will fast for them. And on Taanit Esther, the same thing occurred. Secular people said, we want to fast for them. For those who now fight for the benefit of for the hostages, we want to fast. And all of a sudden, Jewish traditions that usually were so far away from secular thoughts, all of a sudden, became a part of their identity. That's something which is inspiring.

It's very inspiring and you're one of those people that has actually spent your whole life trying to make this happen. God willing, a year from now, when we sit down and we talk, the Haredi thing will be resolved somehow, maybe for the better. Maybe we'll have many fewer young men and women out there at war, and maybe we'll have had a Yom Kippur, where Jews of all different sorts get together in Tel Aviv and all over this country, making a point actually not to pray with the people that they normally pray with, but on Yom Kippur, which was so ugly last year, to make a point of going out with being people that we're normally not in shul with and to begin to build a new future.

You're an inspiration to all of us who live in this country, who care about the future of this country, and very grateful to you once again for our conversation. It's an honor and a privilege to be with you, and to look forward to sharing b’sorot tovot, much better news and brighter days for Am Yisrael.

Shalom, shalom to you and to all the listeners.

Impossible Takes Longer is available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our Threads feed is danielgordis. We’ll start to use it more shortly.

"I still believe that our problems do not start and end with our external enemies"