Drowning in a sea of resentment and hate, it's far from clear that Israel can make it back to shore.

Purim is almost here, but it feels more like the hours before the Ninth of Av; joy barely registers, while dread looms everywhere; the roots of the crisis are as old as Hatikvah

Last week’s “pogrom” (not my word; it’s the term used by IDF Maj. Gen. Yehuda Fuchs, who oversees the West Bank / Judea and Samaria) was unbearably horrific, shameful and a desecration of everything that Judaism ought to stand for.

Full stop. Nothing can mitigate that.

Still, here’s what one needs to understand:

You may or may not be opposed to the settlement project; you may or may not love or even like the religious worldview or politics of many of the people who live there. But to understand Israel today, one needs to understand how deeply betrayed the settlers of Har Bracha and other similar settlements feel. They live where they live with the approval of the Israeli government. Not just right wing governments, but governments of the left as well. They are Israelis, living where the state has told them that they may legally live, and—they feel—they are virtually abandoned—left entirely unprotected by the army. Two brothers getting shot at point blank rage and dying is as much a result of Israeli policy, they will tell you, as it is Palestinian hatred and venom.

Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, the rabbi of Har Bracha, one of the leading halakhic authorities of modern Israel, delivered a eulogy for those two brothers—Hallel Yaniv and Yagel Yaniv—which we quote here in part (we’ll send out a translation of a more complete version in the days to come). [Even if you don’t understand the Hebrew, I urge you to listen to a bit of the brief eulogy, from 2:00-3:00 in the video, for example, just to get a sense of the heartbreak he felt as he spoke.]:

We did not return to this land to dispossess Arabs from their ancestral lands, but rather, to bring goodness and blessing to the world. The Arabs, too, could have benefitted from that. But now that they have decided to rise up against us, we will wage war against them and emerge victorious, [the war conducted] entirely within the rule of law, by the army and police. ….

Beloved settlers, who will tell you how wondrous are even your smallest acts, how great is your courage, as even when you are afraid you continue to travel, by day and by night, to work and to study, to celebrations and to funerals, and you continue to settle this sacred land and to defend with your very bodies this land and its people. …

In the Diaspora, we were not able to bury our dead with honor. A large funeral was liable to spark a pogrom. Jews buried their dead quietly, and in secret they wept over their dead; with tremendous suffering they watched over the embers that they not be extinguished. Today, we are privileged to bury our holy dead in an official ceremony on Mount Herzl.

How blessed are we that we have a state and an army, and with God’s help and with the steadfastness and courage of our commanders and soldiers, we are able to stand up against our enemies, as we continue to build this land and to cause its desolateness to blossom.

But that army, he did not need to point out, does not keep them safe.

The settlers are brokenhearted, and in ways we often don’t appreciate, they feel deeply betrayed by Israel.

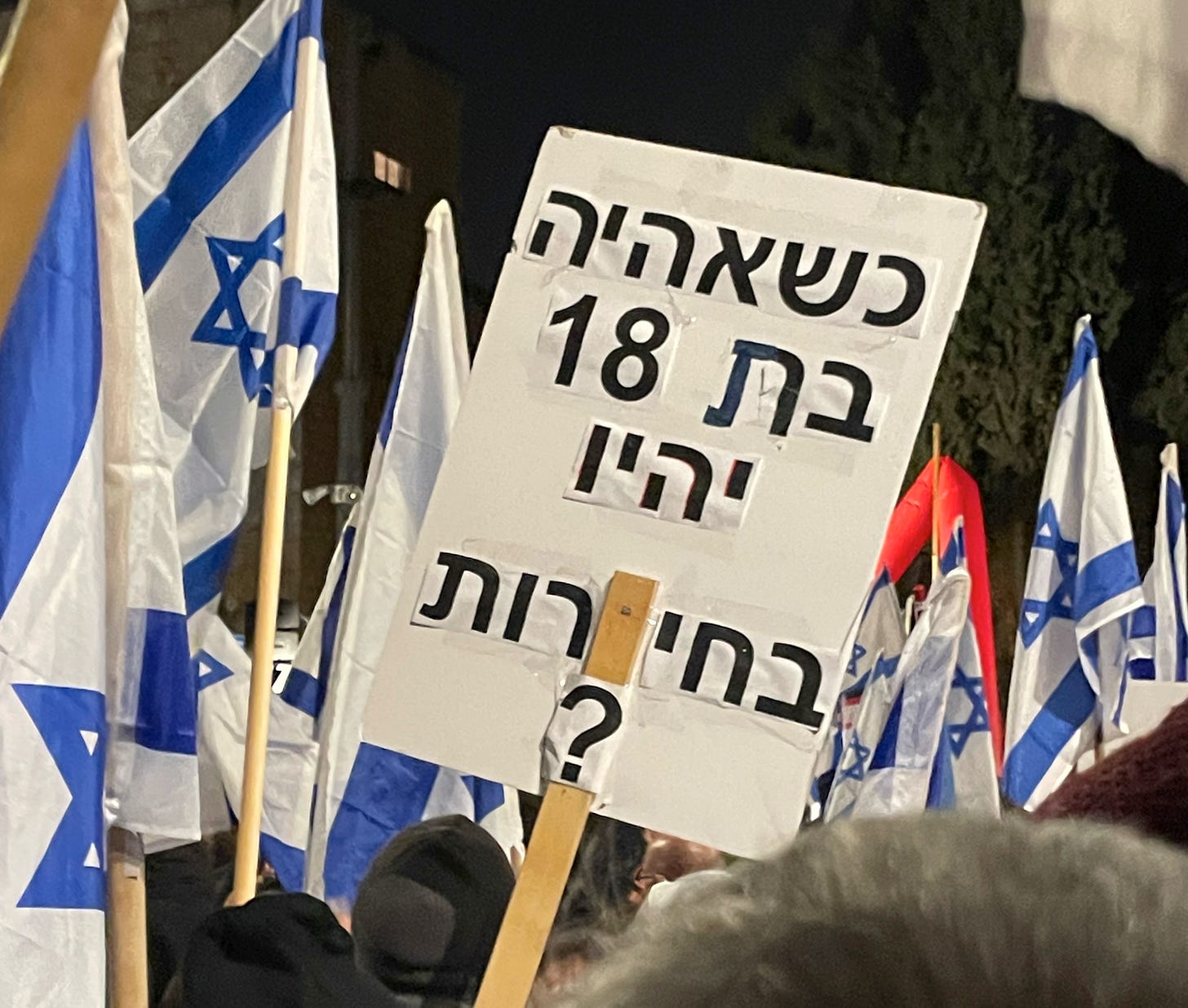

So, too, does the secular left. Why are they are protesting by the tens of thousands, blocking highways, reservists threatening not to show up for military service, pilots saying they won’t join training exercises, the rescuers from Entebbe in 1976 accusing Netanyahu of endangering the state for his own personal good, people taking their money out of the country and encouraging others to do so? Because to them, the sort of illiberal democracy (they believe) Yariv Levin and Simcha Rothman are trying to create in Israel is a betrayal of the very democratic foundation of the Jewish state.

Why, ask these reserve pilots, would they possibly risk their lives and risk turning their children into orphans for a country in which their right to vote is not guaranteed, in which protections that the courts afford to minorities have been whisked away?

It’s still too early to know how this is going to play out (I remain cautiously optimistic that a compromise under which Israel will remain democratic will still emerge), but in many ways, it no longer matters. The fact that we could get this close to an illiberal democracy has showed the secular center-left that Israel is not what they thought it was. Even if compromise is reached, the secular left now knows that large swathes of the country cannot abide them, that a substantial portion of the country does not care if Israel is not a first world country. And they know that even if the judicial revolutionaries don’t win this time, those whom the secular left consider to be “the forces of darkness” will just keep trying again and again.

The center-left feels betrayed by the country their grandparents created.

The ultra-Orthodox feel betrayed by the country. Many of us (myself included) have every right to feel that it’s absurd that our coalition system of government allows their electoral block to squeeze millions out of governments left and right, fund schools that do not prepare their children for (our vision of) the 21st century. But they see things differently. Why does everyone hate us so much, they want to know? Why the tax on soda, which was obviously meant to target the Haredi community? [They consume much more than their share of sugary, unhealthy drinks; the new government has already repealed the tax.] Why force secular education on us if we don’t want it? Why is using our electoral power to get funding for our schools any less legitimate than settlers getting government funding for settlements, secular Jews getting funding for universities and cultural institutions in which we have no interest? Why is the “game” legitimate for everyone, except when we play it?

The Haredim feel betrayed by a country that has never wanted them.

The Ethiopians? It’s getting better, but there have been so many cringe-worthy moments that most of us have lost sight of them. More on that for another time.

The Ethiopians have long felt betrayed by a country that boasted about saving them, but at the same time, mistreated them horribly.

How about Israeli Arabs? We often forget this critical fact: the War of Independence in November 1947 began not as a war against outside countries, but as a civil war between the country’s Jews and Arabs. Those who are today Israeli Arabs (some prefer to be called Palestinian Israelis) come from families that were in the lifetimes of many still at war with this country and the Jews who live in it. The war is over and relations have gotten a bit better, but the dark cloud of that history hovers over everything here. Compare the infrastructure in Arab towns and their schools to that of Jewish towns and Jewish villages, and we know why the resentment persists, why the yawning chasm still exists.

(Oh, and the Druze hate the Palestinians, but that’s another story.)

The Arabs feel betrayed by this country. To put matters very mildly.

And the Mizrahim, those Jews from Muslim lands, who are now a majority of the Jews in the State of Israel? It’s gotten better, but the worldview of Ben-Gurion and his compadres still stings. Ben-Gurion had no shame about saying, quite publicly:

The dispersions that are being terminated [that is, entire communities, such as the Bulgarian and Iraqi Jews, that were liquidated through immigration to Israel] and which are gathering in Israel still do not constitute a people, but a motley crowd, human dust lacking language, education, roots, tradition or national dreams. . . . Turning this human dust into a civilized, independent nation with a vision . . . is no easy task…

Determined to make the state as culturally advanced as it could possibly be, Ben-Gurion went so far as to suggest segregating schools and educating Mizrahi and Ashkenazi children separately, worrying that Israel would become “Levantine” and “descend” to be “like the Arabs.”

To say that the Mizrahim feel betrayed by this country would be an absurd understatement. They feel rage. They hate the elites.

That is in large measure what is playing out here. The parties fueling the Judicial Reform (or the Judicial Revolution, depending on who you ask) are seeking to wrest power away from the (largely Ashkenazi, certainly elite-in-image) Supreme Court.

And those parties would not be in power without the Mizrahim. Bibi’s Likud (which isn’t so much Bibi’s any longer, as he’s lost his grip on just about everything in this country rapidly spinning out of control), Smotrich’s “Religious Zionist” Party, Ben-Gvir’s “Jewish Power” Party and Aryeh Deri’s “Shas” Party all have significant Mizrahi voting blocs. This is not only about Mizrahi rage, but it’s largely about Mizrahi rage. And approve of the proposed legislation or not, one cannot understand this country without internalizing how deep and (often) how justified that rage is.

It’s not only the Mizrahim, of course. We are where we are, to no small extent, due to (entirely legitimate) rage many groups feel towards the founding elites of this country. Those elites are less and less numerous (some say they are about 8% of the country) and less and less popular (Ben-Gurion’s party got 46 seats in 1949, but only 4 in this past election), but they still have an enormous amount of control. True, there are many Ashkenazim pushing for Judicial Reform, but the idea is particularly popular not among the elites, but among the less “privileged” population in Israel. They may not know the details of the proposed legislation (those opposing it don’t, either, of course), but they support it because their parties support it and because they know it is about “sticking it to the elites.”

Israel is a country drowning in a sea of sensed betrayal. It is a country drowning in a sea of resentment. It is a country drowning in a sea of mutual hatred.

It is a country that may not make it back to shore.

So what does Hatikvah have to do with this? After all, what could be more embracing than our national anthem, that soft, soulful, mournful, minor-keyed anthem we’ve all been raised on?

As long as deep in the heart, the soul of a Jew yearns, and onwards, towards the end of the East, an eye still gazes towards Zion, our hope is not yet lost; the hope of two thousand years, to be a free nation in our land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem.

What Hatikvah has to do with it is that a closer look at the anthem shows just how exclusionary Israel’s elite views have been, without most of us realizing it. It’s long been obvious to Israeli Jews that Israeli Arabs cannot sing their own national anthem. What is a Christian-Arab Supreme Court Justice supposed to do at ceremonial moments when Hatikvah is sung? Would we have expected Justice Salim Joubran to sing those words? He said he couldn’t, and most Israeli Jews understood. Now there’s a Muslim Arab, Justice Khaled Kabub (appointed in 2022), on the Court. Should he be asked to sing it?

That’s already 20% of the country that cannot sing the anthem.

But look a bit closer, and read once again the third line. Our eyes, say Hatikvah, were always gazing towards Zion, situated “towards the end of the East.”

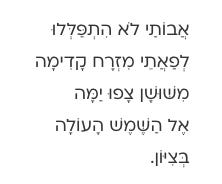

But that’s true only if you lived in Europe (or America). If you lived in Yemen, Zion was not to the East. If you lived in North Africa, Zion was not to the East. If you lived in Syria or Iraq or Iran, Zion was not towards the East. I’m hardly the first to note this. Consider the poem, Hatikvah, particularly poignant on this week of Purim because the poem mentions Shushan, by the Israeli poet, Esther Shekalim.1

My ancestors did not pray towards the end of the East From Shushan, they gazed westward to the rising sun in Zion

There’s no anger in the poem, no venom. But there is estrangement. “You have always spoken about gazing East to Zion—but my ancestors gazed West, from Shushan.” I didn’t come from where you came. My family doesn’t reminisce about Europe. And by implication—in this country you all built, you’ve made me “other,” marginal.

To be sure, when the Zionist movement adopted Hatikvah as its anthem at the First Zionist Congress in 1897, anti-Mizrahi sentiment played no role in that decision. Most of the delegates had never met a Mizrahi Jew. Some may not have even known of them.

In 1935, when there were about 17,000,000 Jews in the world, some 1,000,000 of them were Mizrahim. Mizrahim thus constituted merely 6% of the Jewish people. That does not excuse Ben-Gurion’s elitism and racism, or his inability to appreciate the fact that just because a culture wasn’t like his did not mean that it was not culture; but it does explain how even a decent human being might see the Mizrahim as “marginal.” They lived elsewhere, and they were a tiny portion of the people. What could possibly be wrong with saying “towards the end of the East”?

Except that Hitler (with the enthusiastic help of the Poles and the Ukrainians, among others) slaughtered a third of the Jewish people, almost all of them Ashkenazim. And relatively few of those he didn’t slaughter came to Israel. On the other hand, most of the Mizrahim who were evicted from Arabs lands came to Israel, and they typically had more children than the Ashkenazim. So now they are not a mere 6% — Mizrahim are the majority of Israeli Jews, yet subtly, the national anthem suggests that they are an afterthought in this country.

How is a Mizrahi Jew supposed to feel when singing the anthem that is clearly European in its orientation? How is a Mizrahi Jew supposed to feel on Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, as the air raid sirens sound throughout the country and everything comes to a standstill?

They’ll feel grief, of course, because over the years the Shoah has become less about what happened to European Jewry and more about what happened to the Jewish people. Still, though, it didn’t mostly happen to the Mizrahim or their families or their ancestors. And to make matters worse: what about the destruction of the Jewish communities of North Africa or the rest of the Levant? Where’s the day for that? Nowhere. What about the Damascus Affair of 1840? Why do so few Israeli schoolchildren learn about that? Mizrahi kids should learn about the Warsaw Ghetto and travel to Poland in high school, but Ashkenazi kids should know virtually nothing (at best) about the history of those who are now a majority of Israel’s Jews?

This is not to suggest that we change the anthem (though having one in Arabic that Arabs could sing is an issue well worth discussing, to my mind). It is to suggest that if we Israelis are to somehow make it back to shore, we need to understand how Israel became a country drowning in resentment, to understand how deeply broken it has been from the outset.

“Our hope is not yet lost, to be a free people in our own land.” True, at least for the Jews.

But “our” isn’t as broad an “our” as we might imagine.

If we’re going to repair and heal the rage that beats in the heart of the Israeli soul, we’re first going to have to understand it. This wellspring of hate and resentment wasn’t forced on us by the Ottomans, the British or anyone else. We created it.

What we’re about to find out is whether it is too late to fix it.

Later this week, we continue our conversation with Professor Moshe Koppel, Chairman of the Kohelet Policy Forum, which has been one of the primary forces shaping the proposed judicial overhaul legislation and pushing for its passage.

As part of our conversation, I asked Professor Koppel if, were the currently proposed legislation to pass, it would be possible for the Knesset to close all mosques or non-Orthodox synagogues, with no Court to push back. He acknowledged that it could. Similarly, I noted, by a vote of 80 Knesset members, the Knesset could extend its own term as much as it wanted, and again the Courts would have no power to intervene.

Professor Koppel acknowledged that both of those scenarios would be possible under the legislation that Justice Minister Yariv Levin and Constitution Committee Chairman Simcha Rothman are pushing, but he of course had an explanation of why he isn’t worried.

Agree with him or not, you’ll learn a lot.

The full conversation, along with a transcript for those who prefer to read, will be available on Wednesday to paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

I’m grateful to Regev Ben-David for guiding me to this link. This is but one paragraph of a longer poem.

I think saying that the sugary drink tax was aimed at Haredim is the same false equivalency that banning menthol cigarettes (I don't know if this was passed or only proposed, here (somewhere in the US) is racist (apparently more blacks smoke menthol...). It was a public health measure, and has been proven (in Philadelphia, & I believe in other places as well) to result in decreased consumption. Of course, the companies producing those drinks care as much about public health as tobacco companies...

In my opinion, what we are seeing is the tension between Jewish and democratic coming to the surface. It is the struggle in Israel between group (Jewish) and individual (human, political, civil) rights.

By definition liberalism is a political and social philosophy that promotes individual rights, civil liberties, democracy, and free enterprise.

Whereas Jewish democracy promotes Jewish group rights over and above individual rights. And therein lies the rub.

Hence the need by the religious and the right wing in Israel to rein in the superior court who have a philosophy of protection of individual rights at the expense of group/religious rights. And of liberalism which is at odds with Jewish democracy.

Jewish democracy is, by definition, not liberal, it is, if you like, illiberal. And we can specifically say this in connection with a few important issues—say, three great issues. Liberal democracy is in favor of multiculturalism, while Jewish democracy gives priority to Jewish culture; this is an illiberal concept. Liberal democracy is either pro or anti-immigration for all, while Jewish democracy is pro Jewish immigration only; this is again a genuinely illiberal concept. And liberal democracy sides with adaptable family models, while Jewish democracy rests on the foundations of the Jewish family model as dictated by the rabbanut; once more, this is an illiberal concept.

Once you give up the principle of equality, you have given up the whole game. As in the nation state law. You have admitted the principle that people are unequal, and that some people are better than others. Once you have replaced the principle of equality with the idea that humans are unequal, you have stamped your approval on the idea of rulers and subjects. At that point, all you can do is to hope that no one in power decides that you belong in the lesser group, in Israel that is the non Jewish Group. Or… in this case the struggle between two distinct Israeli groups, those that support liberal democracy versus those that support illiberal Jewish “democracy”.