Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

Forego the Jewish State to save Liberal Zionism?

This week provided yet more evidence that the conversations about Israel unfolding in the US and in Israel could simply not be more different

Two guys are sitting in a bar in Amsterdam. (They aren’t—but bear with me.) One of them was born in the United States, yet left years ago, brimming with distaste for what America had become. Now he lives in Amsterdam and teaches continental philosophy at a university there, enjoying the tulips and the beer.

The other was born in Holland. He spent a few years in the U.S. but hasn’t been back in a while, either. He didn’t like America much, either. Nasty place—anti-intellectual red states, terrible treatment of immigrants on the Texas border, the politics of masks trumping science. The list goes on. “Yup, America’s done,” they say to each other, with knowing nods, as they clink their bottles, taking another swig of the ice-cold Heineken.

They’ve met up at the bar to celebrate the new book that the one who was born in the US but now lives in Holland wrote about the US. The point of the book? Well, the US is highly imperfect, and he can’t really see any way to fix it. The only way to save the American dream is to break up the Union. Create a “more perfect union” by having no union at all.

Oh, and he wrote the book in Dutch.

So here are my questions: First, aside from perhaps getting himself a few reviews in his echo-chamber and maybe another notch on the proverbial academic bedpost, what’s the point of the book? Does he imagine that anyone in America is going to think about disbanding the union because of a guy who was born in America, left it, and bereft of solutions to complex problems, has decided to end the project? Does he really imagine he’s going to move any policy needle in America? And if he really hoped he’d engender a conversation, why did he write the book in Dutch?

I begin with that little analogy because of two very different sorts of conversations that crossed my screen this week, two pieces that I think are emblematic of the radically different conversations unfolding about Israel—one in the US and one in Israel, the latter conversation sadly almost never making it into the English press and thus remaining pretty much unknown in America. (Hence, Israel from the Inside.)

The “two guys in the bar” reflects for me the American Jewish progressive conversation, best seen this week in a review of a new book called Haifa Republic: A Democratic Future for Israel. The book is by Omri Boehm, who, yup, was born in Israel, moved to America, teaches continental philosophy (that part was real) at the New School, and indeed, argues (in the words of the review) that it is time to “forego the Jewish state in order to save liberal Zionism.”

We’re heard arguments of this sort before, most famously from Peter Beinart, who never runs out of explanations as to why the Jewish state should be ended—and who argues in the NYTimes this week that if Israel has a nuclear weapon, it’s only fair that Iran get one, too. “American politicians sometimes say an Iranian bomb would pose an ‘existential’ threat to Israel,” he explains, but “That’s a dubious claim, given that Israel possesses a nuclear deterrent it can deploy on air, land and sea.” Deterrence, of course, depends on a rational actor on the other side. Did anyone notice who was just installed as Iran’s President? And Israel’s just as likely to use its nukes to wipe out another country for no reason, right?

But we digress. Now we have Boehm, and his reviewer, Shaul Magid (who, as in our Amsterdam bar analogy, spent several years in Israel and served in the IDF during the First Intifada), telling us that since Israel has long since become an illiberal state, liberal Zionists are defending something illiberal, which makes no sense. But since they want to be both liberal and Zionists, and since a Jewish state will never be liberal (in the philosophic sense, not left-right), there’s only one solution—ending the Jewish state in favor of a confederation of Jews and Arabs.

I understand how that (temporarily) saves liberalism. I’m not entirely sure how it saves Zionism in any way. And I’m definitely not clear on how it saves the lives of the Jews who live in the Jewish state, but that issue didn’t quite come up in the review.

Obviously, I disagreed with most of Boehm’s argument as Magid summarized it (I confess that I haven’t read the Boehm book, and no, it’s not on my Amazon Wish List). But agreeing or disagreeing is not what’s key. Mostly, I read the review thinking about my two guys in Amsterdam.

These two Jewish guys in America, Boehm and Magid, are having their little echo-chamber pleasure. Fair enough. But, I found myself wondering—other than fueling hatred against not only Israel, but Jews (for example: “The ‘Jewishness’ that Israel seeks to protect is not culture or religion, ‘but Jewish ethnicity, Jewish blood’”), what is this book supposed to accomplish?

Note that it was written in English, and that Boehm, born in Israel, could have written it in Hebrew (I could find no mention of a forthcoming Hebrew version online.) So why English? Because there’s exactly zero audience for it in Israel. Even the Israeli left would pay it no attention; they are adamantly opposed to the occupation, they object to all sorts of Israel’s policies—but overwhelmingly, they’re Zionists. The idea of taking apart the country in which they live, in which they’re raising their children and grandchildren, that they’re working to save—well, it just doesn’t grab them.

So what policy needle is Boehm trying to move? He’ll have no impact on Israel. He’s not going to change Biden, obviously. He’s not going to affect most Republicans. He’s not going to influence the traditional slice of the Democratic party. And as for the progressive Democrats, he doesn’t need to move them. J-Street became irrelevant when the progressives leap-frogged it. If you want to move the needle, there’s no reason to support J-Street. Just contribute to candidates like the Squad and you’ll soon have your policy. (Leave out the middle man, as they say.) Israelis know that it’s only a matter of time.

I won’t list here all the places that I believe that Boehm and/or Magid got their facts wrong, because this isn’t a review of the book, or a review of the review of the book.1 What’s of interest to me is how radically different are the conversations that Israelis (even hard left Israelis—if you have not listened to Alissa Symon’s podcast on the subject, you ought to—several people wrote me to say that she gave the best podcast they’re ever heard) and progressive Americans are having.

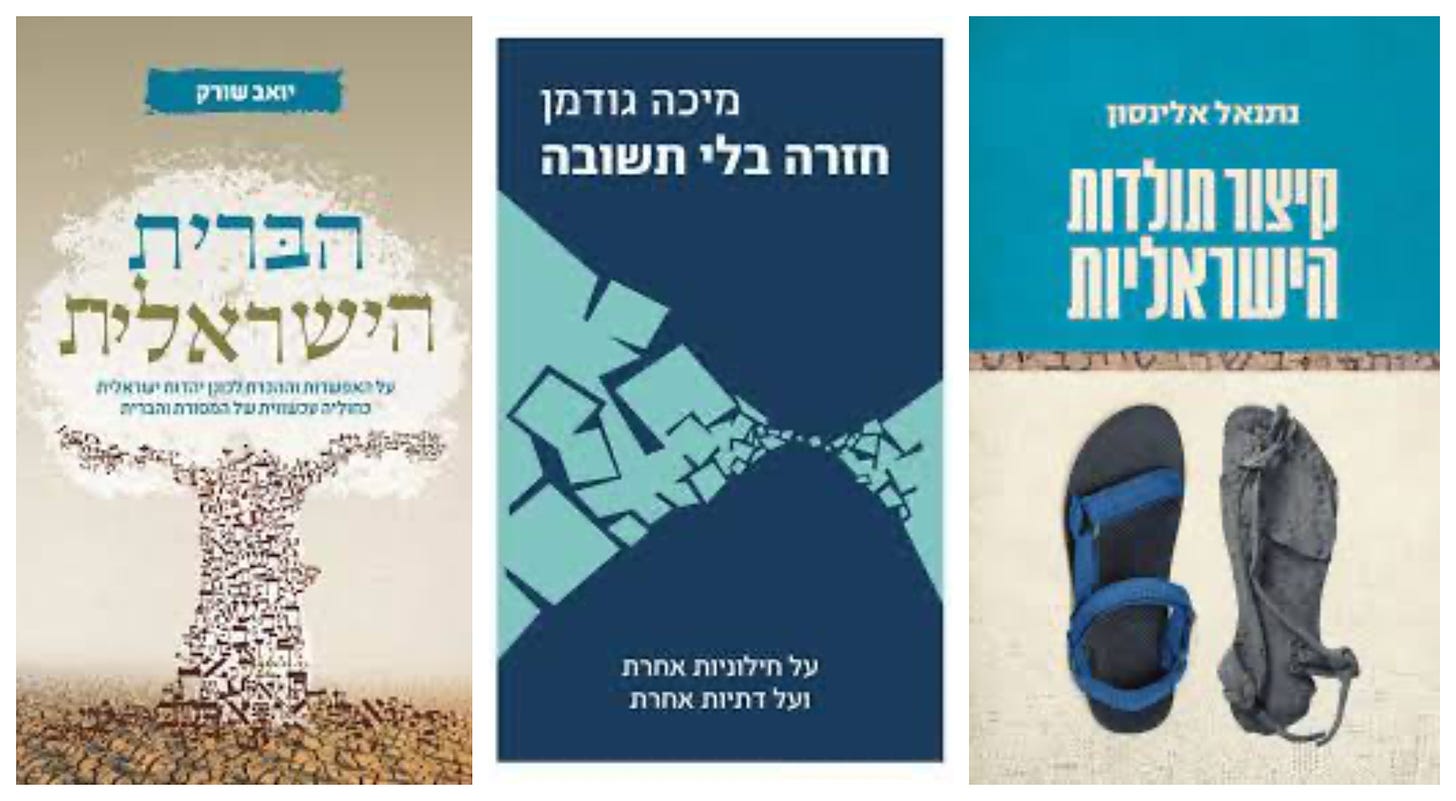

Reading Magid’s review of Boehm reminded me of the book I’ve mentioned a few times but haven’t really discussed at length. It’s Netanel Elinson’s A Brief History of Israeliness [Hebrew only]. Elinson, who also writes a very popular Facebook column and has produced very popular short videos on the land of Israel for Kan TV, had this to say on May 30, as the new government coalition was being formed:

I simply can’t understand this demonic view of the Left, a view that misrepresents reality and is not appropriate to anyone who has in him ahavat yisrael [a love of the Jewish people]. The left is endangering the settlement project? What “Left”? Is he critiquing [the rabbi whom Elinson is discussing – DG] my farmer friends from the Arava [in the Negev – DG] who get up every morning at 4:00 a.m. to work the fields that are on the border? Or perhaps he is referring to all the members of my team [in the army – DG] who do not vote Likud or United Torah Judaism, who nearly 40 years old still do reserve duty, crawling over thorns, their duffels always packed for the next war around the corner?

They’re endangering Judaism? Does he mean the thousands of people who in their spare time study Bible and rabbinic texts? Who try to find a path and a way to connect to their roots and the sources of Judaism even though they vote Left? Is there only one Judaism, in the special color of the voters of the Haredim and religious Zionism? What kind of nerve does it take to tell slightly less than half of the country that they are endangering the state and Judaism? These Lefties are overwhelmingly people who love their people and their land no less than do those on the Right. They just do it differently.

Like Magid, Elinson sees a worrying Israeli tendency to extremism, but he’s devoting his life to combatting it, through education. Like Boehm, he’s painfully aware of the many ills of Israeli society, yet takes them on, to make things better, not to take them apart. Towards the end of his book, he beautifully articulates the genuine openness to differing views he hopes can come to characterize Israel.

Without other streams [of Judaism], the questions that they pose to me and the ways in which they force me to sharpen my views, attributes of mine are likely to become both extreme and destructive. Healthy nationalism can become chauvinist nationalism, universalism can morph into the loss of identity, unpretentiousness can turn into fanaticism, lives of Torah can become lives of disconnection, bravery can become violence, success can lead to an excess of pride, and unity can become a matter of erasing the other.

An article that I recently read about Elinson mentioned that (though he was raised in a settlement, and remains very firmly in the religious camp) he doesn’t wear a kippah. He fears that it gets in the way of building bridges to those outside his community (watch some of the videos mentioned above—you’ll see him teaching without a kippah). Reading that reminded me of yet another Israeli public intellectual, Yoav Sorek, also firmly in the religious camp, who lives in Ofra (a settlement over the green line), has seven kids—and horrifyingly, lost both his father-in-law (in 2000) and his nineteen-year-old son (in 2019) to Palestinian terrorism. Sorek, too, often does not wear a kippah, for precisely the same reason.

I hadn’t read much about Sorek recently. I loved his book, The Israeli Covenant [Hebrew only], and especially his claim that for religious Judaism in Israel to matter, Orthodox Israelis need to be willing to reimagine Judaism, too, so I decided to check out what he’s up to. Turns out, he’s launching a series designed to do exactly that re-imagination.

Reading that brought me back to Magid’s review of Boehm. If Magid is critical at all of Boehm’s book, it’s because Boehm hasn’t (explicitly) despaired of Judaism the way that he has of Israel:

Furthermore, while “Jewishness” is discussed at some length, the book does not address the question of Judaism itself as an engine that reifies Holocaust messianism and serves as a tool of ideological and theological chauvinism, among religious and secular Israelis alike, that would render a binational solution impossible.

There’s no way to know, from this review, how Magid thinks Judaism needs to be reinvented (or trashed) in order to save bi-nationalism, which in turn, will save liberal Zionism, which in turn, will end the Jewish state and in so doing will save … it’s not clear exactly what.

What was eminently clear this week, as both Magid’s review and an article about Elinson crossed my screen, is that what we have are two communities, on two sides of the ocean, both of which know that Israel—like every country on the planet—faces profound challenges, has made grave mistakes, has much work to do if it is to become the society it needs to be. Yet these communities are having very different conversations. There’s the Beinart / Boehm / Magid conversation, all devoted to ending the Jewish state. And there’s the Elinson / Yoav Sorek / Micha Goodman (like many others) conversation, working to reimagine the Jewish state and the greatness to which it can still aspire.

I imagine that some people will find the American progressive conversation maddening or infuriating, but I don’t. To me, it’s merely sad.

Which conversation do we imagine has a greater chance of actually effecting change—those who keep harping about the need to end the state, or those who roll up their sleeves and work to improve it? Which conversation is more reflective of why the Jewish people is still around? (It’s not because we gave up when things got complex.) And perhaps most importantly, which conversation do we think is likely to produce a community that will still be here in fifty years?

For me, at least, striding towards a future—rather than towards oblivion—has always been more compelling. And that, of course, is precisely why those who came before us built this country in the first place.

Israel faces numerous problems; that much, we all know. What we sometimes aren’t as aware of is all the extraordinary people, in both the Jewish and Arab communities, who are working to make things not just better, but much better. In this week’s podcast, I speak with Dani Elazar and Reem Yunis, who work together in the organization called Hand in Hand — a network of Jewish-Arab schools that’s also anchor to a larger social network of parents, graduates and more.

Dani Elazar, formerly of the tech world, is the CEO; Reem Yunis, a very accomplished scientist/businesswoman, an Israeli Palestinian, is on the Board. I met with them both in Nazareth a few weeks ago, and today, we’re making an excerpt of our conversation available. Our full conversation will be posted later this week and will be available to subscribers to "Israel from the Inside."

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

There are plenty of bones to pick, of course, so here are just a few. Magid mischaracterizes Jabotinsky as “reactionary,” when “honest” would probably have been a more appropriate term, given that much of the recent research suggests that Jabotinsky was probably the most committed Liberal of all of Zionism’s great thinkers. He argues that Menachem Begin himself offered the Palestinians “autonomy,” but that’s a bluff—even Begin’s closest advisors, like Aryeh Naor, whom I interviewed for my biography of Begin, are clear that Begin had given the idea virtually no thought and had no idea what he meant by the term: he was just trying to get Carter off his back about the Palestinians. Magid approvingly cites Ari Shavit’s description of the “massacre” in Lydda, when my colleague at Shalem College, Martin Kramer, has shown in a deservedly much-discussed piece that Shavit, like historians who came before him, got that account entirely wrong. For the record, Shavit’s book is lyrical and insightful, and there’s a great deal that I like about it.

Subscribe to Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

Israel from the Inside is for people who want to understand Israel with nuance, who believe that Israel is neither hopelessly flawed and illegitimate, nor beyond critique. If thoughtful analysis of Israel and its people interests you, welcome!