Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

If Israel was a marriage, it would now be waiting in the lobby of the divorce lawyer’s office.

We are drowning in seething mutual resentment, in a sea of hatred.

The following column appeared last Wednesday in Haaretz, the day after the Tuesday protests. I’m sending it out here for those readers of Israel from the Inside who might not yet have come across it. You can find it on the Haaretz website here.

If Israel was a marriage, it would now be waiting in the lobby of the divorce lawyer’s office. The days of arguing about substance are long over. No longer does it really matter to anyone who is not earning enough, who is not helping enough with the kids, who never cleans up around the house, why the intimacy evaporated. Now we are simply drowning in seething mutual resentment, in a sea of hatred.

In the world of couples, this would be considered a broken relationship. It would be over.

Once, we were divided over the proposed judicial reform. Leading centrist scholars reminded everyone that there was room, indeed need, for some judicial reform. Prof. Netta Barak-Corren of the Hebrew University Law School wrote a lengthy, publicly posted analysis of both the need for reform and the problematics of the Levin and Rothman proposals, which promptly went viral.

Prof. Yedidia Stern, formerly the dean of the law school at Bar-Ilan University and now the head of the Jewish People’s Policy Institute, was deeply involved in the negotiations at the President’s residence, desperately trying to fashion a compromise.

Even Moshe Koppel, formerly a professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan and as the head of the Kohelet Forum, is often seen as the academic face of the reforms, called gutting judicial review “stupid,” insisting that he had warned Rothman and Levin of that.

Now, it’s difficult to remember those days. When did any of us last hear genuine discussion of the substance of judicial reform?

The shift came in March and April. When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu fired Yoav Gallant, his own defense minister, for daring to speak out against the reforms, he unwittingly revealed, with a clarity that now could not be ignored, the “people be damned” sentiment at the core of the coalition’s ethos. Spontaneous mass protests on the streets erupted, a flood of Israeli flags blanketed the streets and highways, and most importantly, a surge of renewed Zionism came alive among people who for years had not thought about that word.

Another moment got less attention but spoke volumes: In April, Justice Minister Yariv Levin admitted that elements of his plan would have “ended democracy” because it would essentially give the coalition unfettered power. What Levin never explained was how a proposal that he worked on for decades could have been launched with such a fundamental flaw. He was either lying, and knew the dangers of his proposal, or didn’t care to check.

Either way, Levin’s admission, with the country already seething, confirmed the suspicions of many that this had never been about fine-tuning the judiciary. It was, many were convinced, a project much more nefarious.

“You’re not the person I married.” Whatever one thought of Benjamin Netanyahu over the years, there was no denying his critical role in forging Israel’s thriving economy, or even his unparalleled abilities as a tactician and a master coalition builder. Today, though, it is not Netanyahu who is in control, but Yariv Levin and Simcha Rothman, chair of the Knesset Law and Justice Committee, who together are pushing for and trying to shepherd through the package of judicial reform bills.

Afraid or unable to take them on, Netanyahu is but a shadow of his former self. He has become, in the deepest Greek sense, a tragic figure. His legacy will be having taken Israel’s democracy to the brink, if not beyond.

Why does Netanyahu’s weakness matter? Because the void has been filled by petty agents of resentment and contempt. Whatever animates Levin and Rothman, it is not the preservation of the fragile weave that Israel has always been. If it were, they would have softened long ago. Whether their hatred of Israel’s system of government stems from what some see as the Supreme Court’s failures during the 2005 Disengagement from Gaza (a period when Rothman, Levin, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir all came of political age) or something else, it is hard to say.

But their determination to rip Israel’s democracy apart was on plain display this week. Everyone knew that pushing ahead with changes to the “reasonability clause” would unleash mass protests, but they proceeded anyway.

They have no interest in a proposal by group of leading thinkers to create a new Constituent Assembly, like that mentioned in the Declaration of Independence. The Assembly would tackle the judicial issue outside the toxic setting that the Knesset has become, but the government is ignoring the idea, for toxicity has become their calling card. They wanted the protests—and perhaps blood in the streets as well, to prove that the protesters are “anarchists.”

Rothman et al. subjected Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara to scandalous, vicious abuse in the Knesset this week. She weathered it with class and spine, as she has all the scorn heaped on her in recent months, but it was clear—the government may be getting ready to fire her. Unlike Gallant’s firing, axing the attorney-general would be an unmasked assault on democracy, and they know it.

When Yair Lapid, head of the opposition, called Transportation Minister Shlomo Karhi “a chunk of poison” in the Knesset this week, he was reflecting the protesting public’s sentiment not about Karhi, but the government as a whole.

Israeli army reservists’ refusal to serve is the ultimate indication that Israel’s social contract is in tatters. First it was reserve pilots who refused to train or fly missions. Then it was Flotilla 13 reservists, Israel’s “Navy Seals.” Then, earlier this week, 300 IDF cyberwarfare reservists declared that they would not volunteer for duty if the overhaul advanced, forcing Defense Minister Gallant to warn fellow ministers that the army would “not be able to withstand” key reserve members quitting service.

Those who critique the reservists’ refusal to serve argue that they made a commitment, that duty demands that they fulfill it. The soldiers, in turn, say that they made a commitment to a democracy. If it is not Jewish or not democratic, then Israel is not the country to which they pledged their loyalty, for which many said they would risk their lives.

Even former attorney general, Avichai Mandelblit, warned this week that Israel is on the “brink of dictatorship.” It is not the reservists, but Israel’s government, the soldiers say, that betrayed the sacred pact.

Is it too late to save Israel? Probably not yet, but we are getting close. Not long from now, what little there is to save will bear scant resemblance to what we had before it was sabotaged. The Hebrew image that made its way around social media this week, “The Government of Israel versus the Nation of Israel,” captured perfectly what the people on the street feel. And neither side intends to blink.

Ominously, we have been here before.

We were here in Biblical times at the end of King Solomon’s reign in the 10th century BC. The northern and southern tribes told themselves that their feud was over taxes, but it was, in fact, about jealousy, who was the center. And the first commonwealth ended after 73 years.

We were here when Hyrcanus II and his younger brother Aristobulus II fought in 73 BCE. On the surface, the battle was over the priesthood, but it was really about the fundamental vision of what a Jewish state should be. And after 74 years of independence, the second commonwealth crumbled.

What are we fighting about now, just as we’ve completed 75 years as an independent Jewish state? No one is certain anymore, and it doesn’t really matter. To be sure, it is largely about what kind of democracy Israel will be, if it remains a democracy at all, but by now it is also about betrayal, about a loss of trust, about the erosion of any sense of shared destiny. What was once a conversation about the judiciary has devolved into a flood of enmity, a tsunami of mutual rage.

Israel had always been a marriage of widely disparate groups and visions who curbed their autonomy and power for the sake of a larger whole, for the sake of a national home for the Jewish people.

That is what we were, not long ago. But that is no longer what we are.

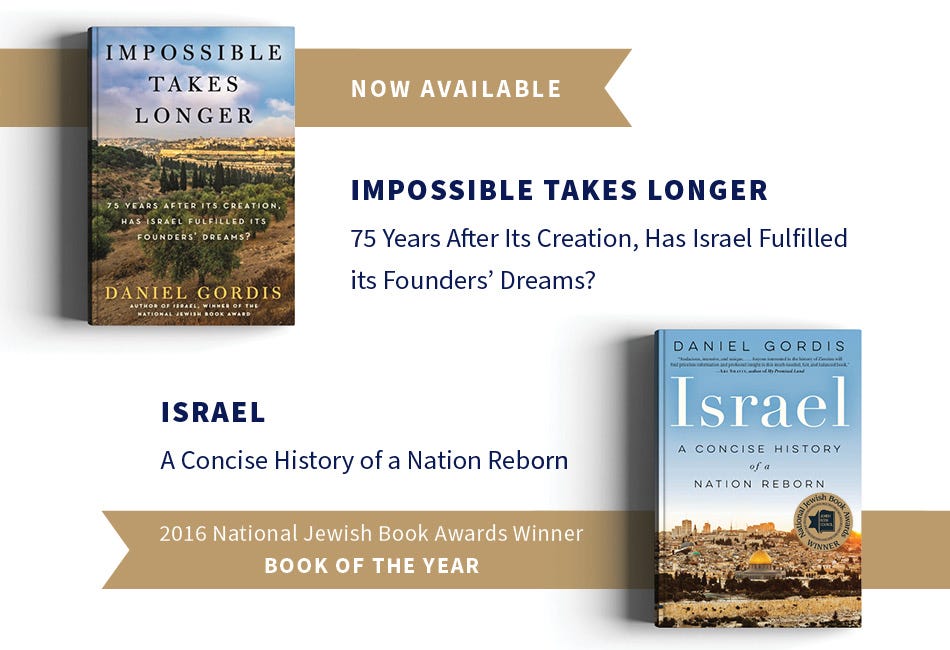

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Our Twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Our Threads feed is danielgordis. We’ll start to use it more shortly.

Define “reasonableness” as defined by the Supreme Court. Then define “reasonableness” in a way that dots not sound like judicial activism and see if there is a difference. The Right strongly believes there is a difference, which is why they think Israel is a judicial dictatorship made up of self-selecting justices. Until the Left can argue otherwise (if they can) or come to a solution (if they can’t dispel the Right’s argument), we are going to continue to have a problem. As of now, though, I have not gotten a straight answer on what “reasonableness” means without it creeping into the territory of judicial activism.

Serve your country well…. Elite military units should not get involved in political posturing. Settle issues through elections and dialogue.