Barely a few weeks into this war, back at the end of October or the beginning of November, we had most of our kids around the Shabbat lunch table. Some have always lived here. Some didn’t then (but are returning soon) and they had chosen to return to Israel to rejoin their unit; some were visiting to check up on us to make sure that we, their parents, were doing OK.

Given geography and the complications of traveling with lots of little children (we’ve been blessed that four more (grandchildren, not children) have been added over the past three years), we’re not often all together like that. So it was a wonderful time, but a fraught one. Several of the boys were at war, and the entire country was still in shock from October 7.

Yet it was also a naive time, a time when we still believed in Israel’s overwhelming power, a time when we “knew” we were superior to anything “they” had, a time when we felt with certainty that we’d get this all done quickly. Had anyone said then that nine months later Hamas would still be fighting the IDF and firing rockets at the Gaza border communities, we would have thought them nuts. The notion that Iran would actually fire 300 rockets at Israel would have been thought “unglued”. So many elements of where we are now seemed then, even though the war had already begun, utterly unimaginable. But here we are.

At that Shabbat lunch, the conversation turned, of course, to the hostages. One of our kids said, during the conversation, “If the hostages don’t come home, this country will not survive. And this country will have no justification for surviving.”

That struck me as a somewhat strong statement, but over the decades, I’ve learned to listen to my kids carefully, because they’re smart and insightful, and I regularly learn from them. I wasn’t sure I agreed with the extreme nature of that statement back then, but today, I think I do. I will explain why, perhaps, in a different column, but today, I essentially share that view.

Often, after we post something about the hostages, I get thoughtful and well-intentioned responses (the nasty ones just get deleted) from people who ask, “But if we have to stop the war to get them back, then Hamas wins, no?” (It should be noted that the majority of Israel’s security leaders are in favor of a cease-fire to get the hostages back.) Or “We made a terrible deal for Gilad Shalit, letting out Sinwar and Deif among many others; we can’t do that again, can we?” Or “Of course we want them back, but isn’t it exaggerated to say that the future of the country depends on getting them home?”

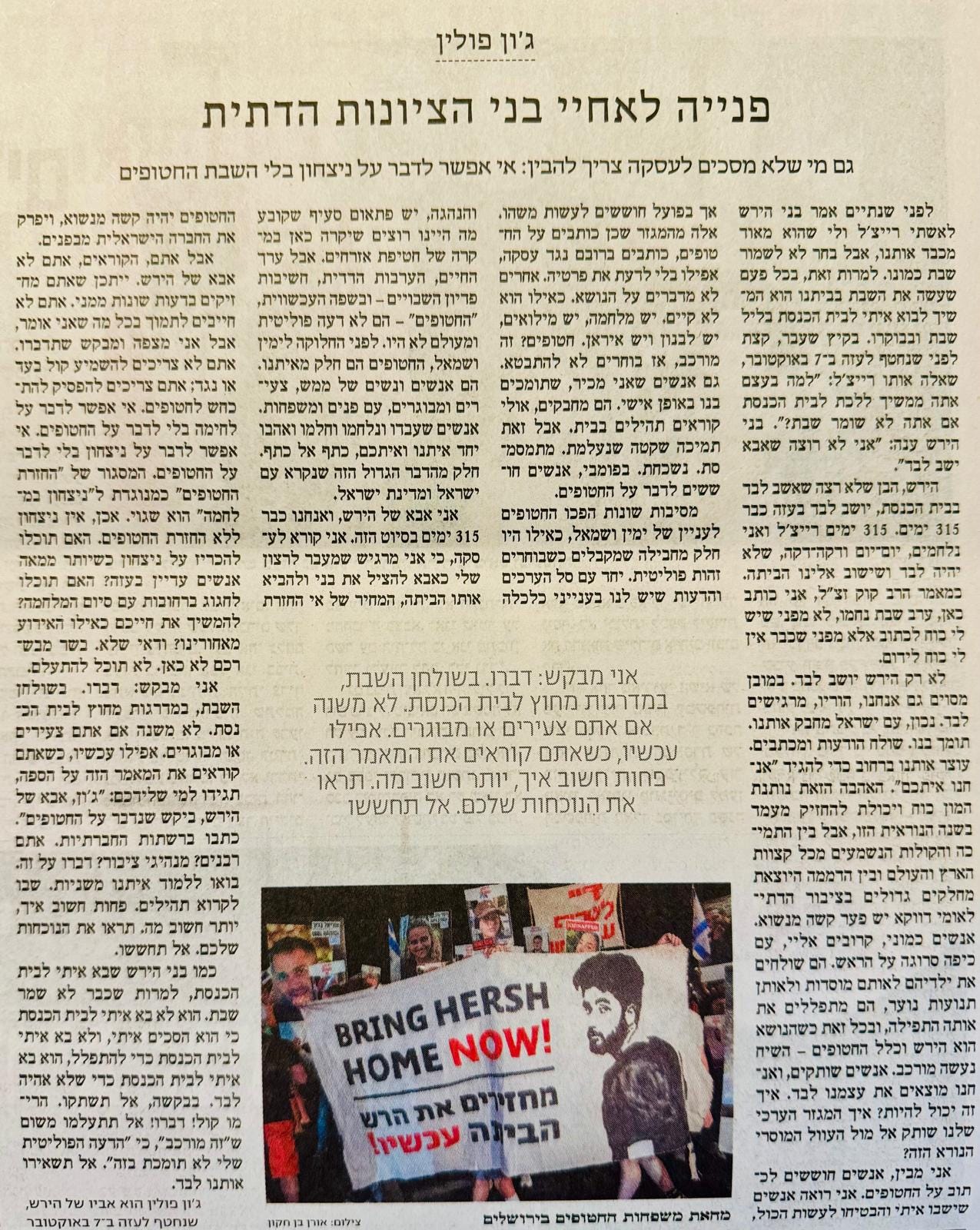

On Friday, Jon Polin, Hersh’s father and Rachel’s husband, published an Op Ed for Makor Rishon, a newspaper we cite often. (A photo of the Op Ed is included below.) I found it heartbreaking and compelling, and after I’d read it, I reached out to Jon and Rachel and asked them if they might share with me and our readers/listeners their responses to the above questions. Even though they were leaving to the U.S. for the Democratic National Convention on Sunday evening, they kindly agreed to sit together on Sunday afternoon.

What follows below is our conversation. Agree or disagree, I hope you will be moved by the depth of their convictions, their sheer courage after ten months of hell, and the dignity and intelligence of their takes on Israel, Judaism and the return home of their beloved son, Hersh.

WEDNESDAY (08/21): How did being away as a reserve soldier for months on end affect soldiers’ spouses and children? We hear from Gabi Mitchell, whose letter from the front we shared months ago, about what life was like in the days after the 7th, and how his kids have changed and how they’ve remained the same.

THURSDAY (08/22): This week, Rachel Goldberg-Polin was stopped in traffic and through the window, she gave a man some tzedakah. He gave her a prayer in return. It’s exceptionally beautiful, and she’s permitted us to share it with you.

FRIDAY (08/23): We don’t usually post much that’s humorous, unless it’s Israeli humor designed to offer a window into the soul of the Jewish state. But earlier this week, a photograph of a book of mine ended up in the Washington Post in the strangest of ways. To wrap up the week, we’ll share the story of how my book, Project 2025 and the Washington Police all met.

Below is the op-ed written by Jon Polin, Hersh’s father, published last week in Makor Rishon. We’re sharing it here along with an English translation (approved by Jon and Rachel) below.

An Appeal to My Religious Zionist Brothers by Jonathan Polin

Two years ago, my son Hersh told my wife Rachel and me that he respects us very much, but he was not going to be observing Shabbat as we do. Despite this, every time he was home, he continued to come with me to synagogue, both on Shabbat evening and morning.

Last summer, shortly before he was kidnapped on October 7, Rachel asked Hersh, “Why do you keep going to synagogue if Shabbat is not speaking to you at this time?” and he answered, “I don’t want Dad to sit alone.”

It has been 308 days, and now Hersh, the son who didn’t want me to sit alone in synagogue, sits alone, held captive, in Gaza. It has been 308 days that Rachel and I fight, day after day, minute after minute, so that Hersh will no longer be alone, and he will come home to us. As Rabbi Kook said, I am writing here, on the eve of Shabbat Hazon [the Shabbat before Tisha B’Av], not because I have the strength to write, but because I no longer have the strength to stand.

It is not only Hersh who is alone. In a way, we, his parents, also feel alone. True, the people of Israel embrace us, love us and support us. They send messages and letters. They stop us in the street to say “We are with you.” This love gives us enormous strength and the ability to endure this terrible year. But the gap between the support and the voices heard from all over the country and the world, in contrast to the silence coming specifically from large parts of the national religious public, is challenging.

These are people like me, who are close to me, with a knitted kippa on their head. They send their children to the same institutions and the same youth movements; they recite the same prayers, and yet, when the subject is Hersh and the other hostages, the conversation is complicated. People are silent, and we find ourselves alone. How can that be? How is it that our value-based sector is silent in the face of this terrible moral injustice?

I understand that people are hesitant to write about the hostages. I have met with people who sat with me, promising to do everything, but in action, they hesitate to do anything. And those from the religious sector who write about the hostages—mostly write only against a deal, without even knowing its details. I see that people don’t talk about the issue of these innocent human souls being held hostage, as if it doesn’t exist. There is war, there are reserves, there is Lebanon and there is Iran. The hostages? “It’s complicated,” and they choose not to speak. Even people I know, who support us personally. They hug us. Maybe they read tehillim [psalms] at home. We are grateful to them for their quiet prayers. But this is a silent support that disappears. Dissolves. In public, people are afraid to talk about the hostages.

For varying reasons, the hostages have become a matter of right and left. As if they are part of the package you get when you choose a political identity. Together with the basket of values and opinions we have regarding the economy and leadership, there is suddenly a line determining what we would want to happen here if our citizens are taken hostage.

But the value of life, arvut hadadit [mutual responsibility], ransom of captives, or in the lexicon of today - the “chatufim (kidnapped)” are not a political issue and they never were. They are not about the division into right and left; the hostages are part of us. They are real people, men and women, young and old, with faces and families, people who worked and fought and dreamed and loved together with us and you, shoulder to shoulder. Part of this great thing called the nation and state of Israel.

I am Hersh’s father. We are already 308 days into this nightmare. I am calling for a deal, because I, personally, feel that beyond my desire as a father to save my son and bring him home, the price of NOT returning them will be an unbearable blow to our national identity and will tear Israeli society apart from the inside.

But you, the readers, are not Hersh’s father. You may have different opinions than me. You clearly don’t have to support everything I say, but I expect, and ask, that you speak up. You don’t need to take a public stance for or against, you do not need to yell. But you need to stop denying the existence of the hostages. It is impossible to talk about the war without talking about the hostages. You can’t talk about victory without talking about the hostages.

This framing, as if the “return of the hostages” is somehow in opposition to “victory in the war”, is wrong. There really is no victory without the return of the hostages. Imagine it for yourself: can you declare victory when more than a hundred people are still in Gaza? Will you be able to celebrate in the streets when the war is over? Continue your life as if things are behind us? Certainly not. “The flesh of your flesh” is not here. You will not be able to ignore it. What will you say after your 120 years in this world, when you face your maker and are asked, “Where were you when your brother’s blood cried out to you from the ground?” Where were all of us?

I beseech you: speak. At the Shabbat table or on the steps outside the synagogue. It doesn’t matter if you are young or old. Even now, as you read this article on the sofa, say to the person next to you, ‘Jon, Hersh’s father, asked us to talk about the hostages.’ Write on social networks. Talk. Are you rabbis? Public leaders? Talk about it. Come and learn mishnayot with us. Sit and read tehillim.

It matters less how, it matters more what. Show your presence. Don’t be afraid.

Like my son, Hersh, who came with me to the synagogue even though he no longer observed Shabbat. He did not come with me to the synagogue because he agreed with me, and he did not come with me to the synagogue to pray; he came with me to the synagogue so that I would not be alone. Please don’t be silent. Let your voice be heard! Speak up!

You cannot ignore it because “it is complex”, or because “my political camp does not support it.”

I ask you now, do not leave us alone.

I'm sitting with Rachel and Jon Goldberg-Polin, who by now need absolutely no introduction to anyone listening to us. Rachel and Jon, I know you're flying out tonight to go to the Democratic National Convention, so your time is always incredibly taken, but it's very taken today. I'm all the more grateful to you for taking some time out of this afternoon, before you head to the airport to continue really your extraordinary work, for having this conversation.

I see this conversation, as I said to you before we started recording, kind of as a Rashi conversation, meaning a commentary on a text, in the sense that on Friday, a few days ago, Jon, you published in Makor Rishon, just to remind everybody, it's a slightly right of center oriented towards the religious community, but what I admire about it is a plethora of views. And Ari Shavit writes for it, and all sorts of people write for it who are religious and non-religious and right wing and not right wing. So, it is religious and right wing to an extent, but very open-minded and very pluralistic in that regard. Jon, you had a piece in Friday's paper, which we are actually including as part of this post. There's a picture of the actual op-ed at the top of the post, and then the translation that you guys have reviewed and that you think reflects as best we can in English what Jon wrote in Hebrew. I see this conversation really, as I said, as a Rashi, as a follow-up to that text, which definitely speaks on its own.

But there's three basic questions I wanted to put to the two of you, and again, with great gratitude for your taking the time to address them. The first, well, all three of them really come from responses that I get from people and there are people who really, who love Israel, who care about Israel, who are Zionists, and who care about the hostages. They're not uncaring human beings, but they write me and they say, “look, I saw what you wrote, or I saw what you posted, and I understand where it's coming from, but look, and here's objection number one, if we stop the war now, then all those boys and girls, but mostly boys, who died in Gaza, they died for nothing because they died to destroy Hamas, and Hamas won't be destroyed, and we'll have lost the war, and Hamas will still be there. So, with everything that we genuinely do feel for the families who are going through this horror, what do you say about that?” So, that's question number one.

Question number two is related, but I think it's a harder and more painful question, which is people, I just had this this past week because I don't know what we posted, but several people wrote me this, and they I said, “look, obviously anybody who doesn't have a heart of stone, their heart breaks for these families and for the people who are living in a torture that we can't even begin to imagine, but we were all alive for the Gilad Shalit deal, and we know that Sinwar and Deif and others got traded out in that deal. How could we possibly make the same mistake again? They're going to give us a list of people. It's going to have some really, really bad guys on that list. As much as one desperately wants to get those people back, how could a country knowingly make exactly this terrible, terrible mistake again?” That's the second question.

And the third question isn't so much a question, but it's to ask you to reflect on something. You've said at various points, and I've listened to hundreds of things that you've said, and I think it was in this past week's thing also, and many others say it. I'll just put my own personal self out there for one second. I agree with it, which is that if we don't get them back, there is no tkuma. There is no bouncing back from this most horrible episode in the history of the State of Israel if we don't get them back. But those are at least the three major starting milestones.

Number one, if we don't destroy Hamas, we've lost the war. If we make a deal to stop the war, then we've lost the war. That's the first point. The second point is the Gilad Shalit thing. Then we'll come back to the third thing afterwards. I really just want to listen to the two of you.

Jon: Well, thank you for having us and giving us this opportunity. It's such an important subject, which really is the core of why I published that piece in Makor Rishon. It wasn't necessarily to answer all these questions. It was to spur conversation. I will say that it is certainly not only the typical Makor Rishon audience, by which I mean more religious, more right wing, that has been voicing some opposition to any deal that would release hostages, but they seem to be the ones who have the most vociferous opposition to a deal. And so, it felt particularly important to create conversation within that audience.

I know we both have a lot to say about all of the questions that you posed, so we can take them one by one. But I guess I'll just start by high leveling some of the thoughts that I've got or the questions that I would ask back to the opposition. You talked about tkuma or shikum, the ability for us, resilience to bounce back and rebuild after the tragedy of October 7th. A counter that I would make to the, well, we must wipe out Hamas now, is through the lens of the hostages, the hostage families, but really the country, which is, how can we bounce back?

How can we do the shikum or the tkuma if we don't bring home the hostages. I don't even like to ever differentiate one population versus another when it comes to who's being held hostage. But I will point out here that this is not a typical hostage situation, if there is such a thing.

Gilad Shalit was a soldier taken in uniform. Again, I don't want to differentiate. That's not my point here, but I think we can all agree that there are hostages in this population who are outside of any realm of, not that anybody should ever be held hostage, but any realm of what is acceptable anywhere in the world. Eighty-six-year-old men, there were eighty-six-year-old women as well. They got released after 50 days. But 86-year-old men do not belong in any hostage situation, anywhere in the world, in any country. It's unacceptable, and we got to bring them home.

Now, one and a half and five-year-old brothers, at the time nine months old. The youngest has spent more time in captivity than out of captivity. I'm talking about the Bibas brothers. So, the young women, and on and on and on. It's just so important that we never lose sight of who is being held. And Rachel has been probably the most vocal advocate in the world for 317 days talking about the breadth when it comes to the nationalities represented. There were 40 countries represented in the initial 251 hostages. Now we're down to 23 countries represented with nationalities in the remaining 115 hostages. Rachel has talked about the five religions that are represented. So, this is not that there's ever a normal hostage situation, but this is extreme in every sense of the word, and we cannot lose sight of that.

I would pose a few questions that I've asked of people who push on “why would we do a deal?” The most basic question I have is, for those who are in opposition, they're opposing a deal when we don't yet even know what are the details of the deal. There have been versions that were leaked, there have been rumors, but there are people from the five active parties to this, at least those five, and maybe there are others, but I mean, Israel, the United States, Qatar, Egypt, and Hamas, who are working through details now. I think it’s irresponsible and dangerous for people to be vocally objecting to a deal when they don't know what the contents are of that deal.

I will go on and say it's day 317. From our perspective, day one was the time to get hostages back. But I asked people who oppose, is there some milestone date? How long must these hostages suffer? Must they pay the price on their backs before the opposition gets to a point and says, okay, this population has paid enough of the price. They no longer should pay that price. Is that day 417, 617, or is there no such date? These people should just continue to pay the price and suffer. I'm going to pause because I've done a lot of talking. I've got more comments and more questions, but I want to have Rachel jump in here.

Okay, Rachel is going to speak. Let's just first focus on that first question. We're never going to be able to say we won this war if we stop the war now in order for a deal. Then we'll come back to the Gilad Shalit analogy.

Rachel: Well, we talk with a lot of these families, tragically, who have lost children in this horrifying war. And what they have actually said to us is their sons, we've only spoken with families who've lost sons. As you mentioned, there are certainly families that have lost daughters fighting in this war. Their sons will only have died in vain if we don't get back the hostages because their sons were only trying to get back the hostages. Of course, they were trying to destroy the people who were holding the hostages and the people who designed and committed atrocities on October 7th. But that their real motivation, these boys, when they would leave on Sunday morning after being home just for a very short pause, their motivation and what kept them going, and they send pictures to us of them in uniform and in a little pocket in front, having a picture of one of the hostages. That's what keeps them going.

And so, they have said to us, the only way we will recover and the only way our son will have not died in vain, is to get back these women, these children, these elderly, these regular young men. That is the only way we will recover and move on and find any, any comfort. So that's something very important, I think, on a national, psychic level to remember.

And for people, as Jon said, who feel, you know what? It is very sad that there are 115 people there, but we are going to continue riding on their backs because we feel that this is more important to keep the war going. To them, I would say, first of all, you're welcome to have that opinion. That's what's so beautiful about being in a democracy. You should voice your opinion if that's what you feel. What I would recommend is let's take a pause. And if you feel so strongly that we need to have 86-year-old Shlomo Mansour there, it doesn't have to be Shlomo. Let's pause and put your 86-year-old grandfather there or 86-year-old father there and let Shlomo out, because I think he has served his time. If you feel voraciously strongly that we need to have a one-and-a-half-year-old child there, let's pause and you put in your one-and-a-half-year-old baby or nephew or grandson. But I think Kfir has served his time. If you are committed to having a 40-year-old woman there, great. Put your wife in and bring out Carmel Gat. She has served her time. And on and on and on.

I just think at a certain point, if you feel so committed that these people should be there for us to ride on their backs to continue this war, then put in your people because our people have served their time for 317 days.

I feel that this is so not the Judaism that I was taught, halakhically or otherwise. I think all of Judaism is very irrational. We know that. There are two different types of mitzvot that we talk about in the Torah. There's the chukim and the mishpatim, the things that seem rational, although a lot of rabbis in our tradition say it's all irrational. That's the point. That's the beauty of Judaism.

It is all irrational. Shatnez…why can’t I wear wool and linen together? Why can't I eat a cheeseburger? Why can't you have marital relations at certain days of the month. Why on a day when there's a massive blizzard and it's your daughter's bat mitzvah and you have to walk two miles to shul, why can't you get in a car? Why are we chopping off part of our baby boy's anatomy when he's just come out of the womb eight days earlier? These are all things that are irrational. These are the things that define us. This is what makes us Jews. We are not irrational people because we actually believe that there's someone bigger who's in charge, who's steering the ship. And I think that when we get caught in the spider web and entangled in these arguments of only intellectualizing what is going on here, it for me doesn't feel like a Jewish perspective. It's not Judaism. So, that's when my cognitive dissonance kicks in.

But I do think that there's this idea that we like to pride ourselves on as Jews when we say we see the whole world in one person and not this one person as just a drop in the bucket in the whole world. And I think that if we decide to do the narrative of we're going to be like everybody else, and we're not going to go to the lengths that we, as Jews, go to, to do extraordinary things for our people, That's fine, but you are changing forever more the narrative of what it means to be a Jew, and you need to be ready for that, because we can never again say that we value a life in a different way than others. I personally am not ready to do that.

But if people want to do that, you can't pick and choose. If you decide to leave those people there, you need to rewrite what it means to be a Jew forevermore. And when your children and grandchildren look at you, when you go to tuck them in at night and you say, “I love you, sweet dreams, you have to also say, but if someone comes and drags you from your bed in the middle of the night, we're not coming”. And you have to be ready to really look in your child or grandchild's eyes and say that, because that is what we are teaching them forevermore. We're not coming.

Well, there's so much to ask about that because it's so profound, but we'll come back to it. I want to use that as a segue to get to the second part of the same question about Gilad Shalit, because somewhere in the midst of this whole horror, I actually spoke with Ari Harow. We interviewed him on the podcast. Anybody that wants to listen can go back and hear the interview. His book about Bibi had just come out. And Ari said that one of the reasons that Bibi was in favor of the Shalit deal, in fact, Bibi orchestrated it and made a point of showing, of course, to walk him off the plane. Okay, whatever. He said that one of the reasons that he felt that Bibi wanted to get him out or felt a desperate need to get him out was that Bibi was still then thinking about sending young men very, very far away to the east to take care of the enemy that we're now waiting to see what's going to happen. And he wanted all of those guys to fly east knowing that if anything happened, we were going to get them back.

It's just, if Ari Harow is right about that read of Bibi, and again, we're going to keep this non-political for right now, but if he's right about that, then one would hope that that echo of… as you were saying, sure, sit down. I have a grandchild. So sit down next to your grandchild and say, Okay, sweet dreams. But you should know that if anybody comes and gets you in the middle of the night, we're not coming to get you. But it even makes me cry just like imagining the targil, the exercise, and that he was at that place once, according to Ari, at least, that he wasn't willing to send soldiers to Iran without getting Gilad Shalit back because he wanted them to know that whatever happens, we get you back to where we're at now.

But I want to then come to Gilad Shalit. The second version of the question that I get, and you'll both speak to it, is... I mean, you've been asked it a thousand times, but it was a terrible deal. It was 1,027, 1,021, whatever, 1,000 something, including some very, very, very bad guys, including people named Sinwar and Deif who came back thoroughly knowing Israel, speaking Hebrew fluently, having in Sinwar’s case, been saved by an Israeli surgeon because he had brain cancer, I think it was.

What kind of crazy country, with all due respect to the unbelievably heartbreaking situation that we're in, what country looks at the horror of what's happened since October 7th and says, yeah, that was a really bad deal. You know what I think? I think we should do it again. Again, this is not Daniel Gordis speaking, obviously, right? I don't agree with that. But I get it from people who are good people. I get it from people who love Israel. I get it from people who really do care about Hersh, and they really do care about the others, but they're trying to think as Zionists, so to speak, and about the larger entity.

Rachel: They're thinking rationally.

Right. Okay.

Rachel: Which I will remind you, in my mind, is not Jewish.

Okay, but we're not all entirely irrational. We're not entirely irrational.

But I'm saying it's not that…

Right. Okay. But what would you say to people who really say, look, of course, we got to get them back. And Rachel's right. Maybe you've just convinced me that Judaism is completely irrational. I have to rethink what Judaism means altogether, even though I'm in my 70s or 80s. I got a lot of rethinking to do. Okay, but it was a terrible deal. Why would a country let those bad guys out again?

Jon: So, I'm going to use my rational side here and say that it has been the ethos of this country. It was the ethos of this country for 75 years that we would do anything as Ari talked about in what motivated Bibi. It's ironic. I'm now actually reading a book that was gifted to me by Gal Hirsch, who was the government-appointed, Bibi-appointed hostage Tsar. He probably has a more formal title than that. In his book, he quotes a longtime Air Force chief named Herzl Bodinger, talking about what we as a country do is make sure that any soldier that we are sending on a mission goes on that mission knowing beyond any shadow of a doubt that we will do whatever we got to do to bring them home if they ever get taken.

And so, I turn that around on him now in his position and say, you were inspired by Herzl Bodinger’s quote. Make sure that you have that quote on your mind every minute of every day that you are in this position. We talk about the irony of it being Bibi Netanyahu's brother, at Entebbe, who led that mission, who gave his life in that mission to do something seemingly crazy, seemingly impossible, but we sent him on a mission to do that and to bring back Israelis. That is what we do, we, Israelis.

How much more so when we're talking about 115 and when we're talking about, as we've already gone through, babies and young women who, God forbid, might be impregnated. When we're talking about 86-year-olds. Any rational question about what if, the rational question is, how do we not bring these people back?

And then I'll touch for one second in my rational side on the security component… Have we made mistakes? Clearly. October 7th was a failure across the security, intelligence, political, military, every level of this country. But I don't think that we can now say, we don't trust anybody. We don't trust any of our systems, which is to say it has to be on our military, security, political establishment to ensure the safety of Israeli citizens. It should not be on the back of 115 innocent hostages who have paid the price for 317 days. It makes no sense to say that they should keep paying the price rather than putting the onus on our military, political, intelligence establishment to do what they have got to do to protect Israelis. In this case, those systems, not the political yet, but the military, the security, the intelligence establishment at large are saying, let's do this deal. We will be able to handle whatever the price is. For those who oppose it, what do they know that our system leaders don't know?

Okay, the last thing that I want to ask you both about, you used in the beginning this word tkuma, which doesn't really have a great English translation, but it has to do something with national rebirth or national renaissance. I mean, the word ‘kum’ to stand up. I mean, it's the first sentence of the Declaration of Independence. That's the first verb is to rise because that's the story of this thing. You've said, and I think, Jon, you wrote in your piece that if we don't get them back, there's no tkuma. There is going to be no national rebirth if we don't get them back. That sounds highly counterintuitive.

I'll say, I told you this before, but right after the war started, I forget if it was at the end of October, the beginning of November, we have kids in the States. We have kids here. But everybody converged. And one of my kids said, and this is nice, and I know you have this experience, too, that your kids are wise enough that you listen to them because you learn from them. And that's a great place to be in life. One of my kids said, if we don't... I mean, it was obvious we were going to get the hostages back. And it was obvious that 10 months later, there was not going to be a Hamas that was firing rockets and killing two reserve soldiers over Shabbat. It was just obvious. Okay, we were naive about a lot of things. But he said, if we don't get those hostages back, this country has no raison d'être. I mean, he didn't use the French because he was raised in Israel. But he said, if we don't get the hostages back, there's just no meaning to the existence of this country. And that's a sharper way of saying what you've said, which is that there's no tkuma without getting them back. Look, this country has to be rebuilt completely from the ground up. We are in 1948 all over again, also in the sense that the outcome of the war is not clear, as was the case in 1948.

But let's assume, God willing, we see this through, and the war comes out in some version that we can live with. We have to build everything all over again. Why do you say, and I'm not disagreeing with you, so please don't misunderstand me, I completely resonate to it. But when you say there's no tkuma, there's no national renaissance, there's no rebirth, there's no rebuilding, there's no standing on our legs again, if we don't get them back, why?

Jon: I think having enemies on our borders who declare that they want to wipe us off the map is a tangible thing. But as you were asking the question, I'm thinking about this, and I think as tangible as that is and as unfortunate as it is, it's a different level than the emotional level of who we are as Am Yisrael. We are people who, with all of our differences, we care about each other, we do irrational things for each other, we go to the ends of the Earth for each other. I think that as much as the rational side of people's brains is talking about an enemy who wants to wipe us out, I think emotions are such a strong thing. I want to believe, and I'm not objective. I'm the father of a hostage. I can't be objective, but I want to believe that everybody in this country, everybody in the broad Jewish people, has an emotional investment to these people who have been held. I think a lot of people are asking themselves the question of, what if it had been mine? It could have been mine. It was by chance that the people got pulled out of their beds who did get pulled out of their beds. It was by chance that people who were at a music festival were at that music festival.

I think everybody asks themselves, what if this had been me or my family? And that that emotion has everybody understanding that for them, for all of us to overcome this, we are not complete, we are not whole until we bring these people home. I think there are other levels to this answer. Again, Rachel talked about how core this is to who we are, and we've talked in the past, but conveniently, we just read Parshat Vaetchanan yesterday with the Aseret Hadibrot [10 Commandments]. It starts with, I am the Lord your God who took you out of the land of Egypt. Out of slavery. God doesn't choose to say, I created the world. I created man. I created. I did. The message he uses to establish his credibility, his power, is, I took a people in need out of bondage. That is such a defining characteristic of who we are as a people. Even people who don't know Parshat Vaetchanan and don't know our Tanakh, our Bible, I think that there is just something about that element that is ingrained in all of us, and that is why we cannot begin tkuma or shikum, knowing that we have people in captivity, and we have not done every single possible thing to bring them back where they belong.

Rachel: What's very interesting is, first of all, I remember reading, I want to say it's in Pirkei Avot, but it might not be, where we talk about not judging something until you know the whole story. So, I always think it's very on point when Jon says, how are people screaming in the streets being anti-a deal when we don't know what the deal is? So that already, I think, is problematic, just Jewishly speaking, halakhically, from a Jewish legal perspective.

But I was very curious a few weeks ago about, I was remembering Blackstone's paradigm, the idea that was from the mid 1700s, this idea of it's better to let 10 guilty men go than to have one innocent man hang. And that was what all of modern Western judicial systems were based upon this premise of presumed innocence and how important preserving innocence is and what is the reason for that. It's that innocent people have to know that there's a reason to try to be a law-abiding citizen. And if you don't have the assumption that you are going to be viewed as someone worth saving, then it makes society devolve into a non-law-abiding society.

What's interesting to me is that was Blackstone's paradigm, which I did a little bit of research on, and I found out that Benjamin Franklin actually said, no, it should be that you're willing to let 100 guilty people go in order not to have one innocent person suffer needlessly. But it turns out, Ben Franklin, who was so cool, I just watched- about a year ago- I watched a huge many-part documentary about him, and I highly recommend it. It was on a PBS. It turns out that that was based on someone he had studied who was not as well-known, in Ben Franklin's day, a philosopher, physician, and rabbi named Maimonides, who actually said, better to let 1,000 guilty people go than to have one innocent person suffer.

And I really think that is screaming from the ground when we talk about when God asks Cain, where were you when your brother's blood was screaming out from the ground? And when we are told in Leviticus, you are not allowed to stand by when you see something unjust happening. And I think that, again, going back to what I said at the beginning, I think what makes Jews so special and so different and so holy. And when I used to teach in America, and I would say to people, what does this word kadosh mean? And everybody says, oh, it means holy. And I'd say, great. What does holy mean? And they'd say, sacred, hallowed, these bizarre words that have no real umph to them when you really start to dig onto them. Really, kadosh and holy means separate, and it means different, and it means special, and it might even mean a little bit crazy. And audacious. And that's who we are, that we even think that we, this tiny, what were 1% of the world population, that we think that we can really make it. And we have never given up that idea that we have a right to be in this world, whether with a country as we have for these last 70 plus years or without a country for those 2,000 years before. We are an audacious, vivacious, daring, and sometimes crazy people. And we do insane things sometimes because that's what we do. And that's what makes us different. And special and sacred.

And I pray that we merit to hear miraculous and joyous news soon, and that we can all start healing, because we say there are 115 hostages. There are nine million hostages being held right now. We are all being held hostage right now, this entire country. And I would even dare say the entire Jewish people worldwide are being held hostage. And what we decide to do now is going to decide, can we be like the Phoenix that rises again? Or are we going to change our path and change our story, and change our narrative, and change everything that we've ever claimed to be?

That's really, really beautifully put. So, I won't sully it by going anywhere else. We'll leave that in the air. I'll just say this one thing that I know you're heading out tonight back to America, and you've been tireless. You have really defined what love and devotion for a person one loves is. I think when anybody for decades thinks about that, this is the model of what absolute selfless devotion looks like.

I hope that the trip is successful and has the impact that you wanted to have. You were talking about praying before. So, I'll tell you, when I think about the two of you, specifically, what my prayer is. I used to think that my prayer was that I would go back into shul and I would see Jon sitting towards the front on the right there, and that Hersh would be sitting next to him, just like you wrote about so beautifully, Jon, in this piece this past Friday. And we'd be like, Oh, my God. Oh, my God, who's there? But here's what I really think I pray for. I pray to go back into shul and see Jon sitting in the front and to see Hersh sitting next to him and it not being a very big deal because he's been back for so long and he's been reintegrated into our society and all of the hostages, the young, the old, the women, the men, the firm, the infirm, everybody, we'll have had them back and helped in their shikum, in their rebuilding for so long. And we'll be able to take such pride in who we are and that we'll look at them with a certain amount of pride, but we almost at a certain point we'll say, yeah, well, that's how we roll, we Israelis. We bring our people home. I just wish, I pray for that day to come very soon. I wish you guys tremendous success, continued strength. Thank you for taking the time and for sharing these thoughts.

Rachel: Thank you for the opportunity. Amen, amen.

Jon: Thank you for elevating this important conversation.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Jon Polin: "An Appeal to My Religious Zionist Brothers"