On this week of July 4th, a conversation with an American Jew who, as ambassador, had to give up his American citizenship in order to serve his country. For American Independence Day, his thoughts about his generation of American immigrants to Israel, those who followed, and those who still might …

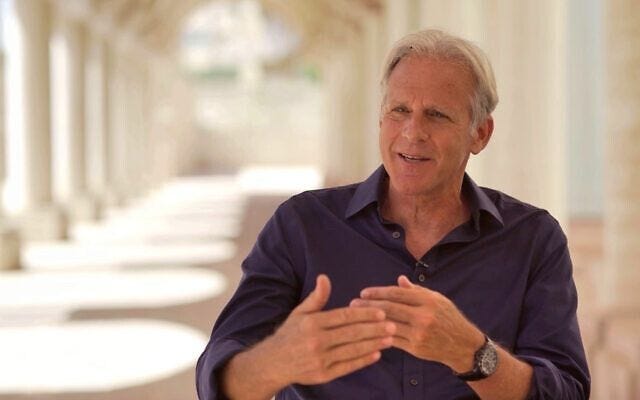

It’s hard to think of anyone else in the Jewish world who has distinguished himself or herself in as many ways as has Michael Oren. A world-class historian with New York Times bestsellers to his credit, a professor at leading American and Israeli universities, former Israel Ambassador to the United States and former Member of Knesset, Oren is also a novelist, with another book of fiction coming out soon.

Michael and I have been friends for years, since we worked together at the Shalem Center, and I read whatever he writes with great interest. Not long ago, Oren published a piece in Tablet Magazine, in which he reflected on his generation of immigrants to Israel. I sat with Michael to discuss his article, to hear his reflections on aliyah since his generation came, and his surprising suggestion that Israelis actually don’t want more immigration.

What did he mean? And why is he still optimistic about American aliyah? Oren is always a delight to listen to and learn from, and if you click above you can listen to the conversation with him, which this week will serve as our Monday posting; the regular weekly podcast for subscribers will appear as always later in the week.

We know that some subscribers prefer reading these conversations to listening to the audio, so we are providing a very basic transcript. Please note that these transcripts are machine-generated, not carefully edited, and very often trimmed, often substantially, because they can become very lengthy. Enjoy!

Our generation, we came out of a particular soup, a historical soup. This was the post Holocaust generation. We grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust. There was a deep sense in our parents’ generation, even though some of our parents had fought in World War II, my own father landed on Normandy Beach, that we had not done enough to save European jewelry, sort of a collective sense of guilt. It was the Six Day War that gave American Jews the strength and courage to speak about the Holocaust. It's no accident that Holocaust Studies grow up in the aftermath of the Six Day War. We used to whisper about the Holocaust. I will never forget at 15 years old seeing Elie Wiesel on the stage of my JCC, and I'm saying, “My God, there's a man on the stage talking about the Holocaust. How could that be?” And it's hard to imagine today. It's hard to imagine today, 3 million Jews living behind the Iron Curtain who didn't have the right to speak Hebrew, to study Hebrew, to study Jewish texts, to immigrate to Israel, in a sense, prisoners, prisoners of Zion. But the Six Day War also ignited their fervor about getting out of the Soviet Union.

What we remember about the Six Day War was the great victory. But the three weeks preceding the Six Day War was called the waiting period where we were convinced that certainly my parents would witness the second Holocaust in one generation, and nobody was going to do anything. The United States wasn't going to do anything. Even American Jews weren’t going to go do anything.

My generation was also a generation of great activism. In one week, you could protest for Soviet Jewry and against the Vietnam War. We were a generation of Jewish fermentation, of towering figures in all different directions, whether it be Meir Kahane with radical violence or Shlomo Carlebach with love and peace. Interesting religious leaders, both in the reform and conservative movements and in an Orthodoxy. The generation of Soloveitchik, of the Havurah movement in the conservative movement. There was a Jewish effervescence happening. I think there was also a sense of beginning to acknowledge that our own Jewish lives were kind of vapid and lacking a strong spiritual connection. And there was also a sense that Israel needed us in the way that maybe Israel wouldn't need us today. We talk about Israel being isolated at the time. Today Israel is profoundly not isolated. Israel back then, not only was there no peace with Egypt and Jordan and certainly no peace with Abraham Accord countries, but Israel also didn’t have relations with China. China was a hostile country. India was a hostile country. The Indians wouldn't play with our badminton team play or our chess team.

Then there were the Soviet bloc countries, which were twelve countries. After the 1974 oil embargo, 24 out of 25 African countries cut off ties with us. We had scant relations with Latin America. We had a friendly relationship with the United States, but not have a strategic alliance with the United States. Israel was embattled and endangered and so American Jews came. And certainly, in the wake of the Yom Kippur War. What was the country that we encountered? We encountered a country that was lower middle class, had very few social divisions. Everybody earned pretty much nothing. It used to take three years to get a telephone. There was no food. Even the falafel was bad. And there were no restaurants. There were no nightclubs. There was television for about 2 or 3 hours a night on one channel. When Hawaii 5.0 came on the streets were empty. And the kibbutz movement was a serious movement, still a powerhouse in the country. And the Mizrachim were still very much downtrodden. It was a very different country, a very poor country. The expectation of new olim was that they would go in the army. If you were in your 30s you were still going to the army. And there were a handful of lone soldiers and there were no benefits for them.

We were the most unusual olim because the Zionist model, the paradigm is that people make aliyah to this country because they're poor and oppressed and they're looking for refuge. Now we experienced anti-Semitism in the United States. There's no question I experienced anti-Semitism growing up. I experienced anti-Semitism throughout my high school years, my college years. If you played sports in university, you were being called all sorts of names. And there was always a sense that we were Americans, but with the asterisk over Americans, we were American Jews. We're hyphenated. We were also the last generation of Jews in the United States who were a distinct ethnicity. In your books, you write about how American Jews think of themselves as a religious group today. But back then, we weren't a religious group. We were an ethnicity. American Jews today, even Orthodox American Jews, Haredi American Jews don't ask that question. They don't even understand the question.

The irony of it was that in America, we were Jews, and we were not accepted by the Anglo Saxons who wouldn't let us into their universities or quota systems. There were no Jews on sitcoms. There were no Jewish astronauts. And then we get off the plane in Israel and we become “Anglosaxim”. So, in the United States, we were a Jewish ethnic group, and in Israel, we were an American ethnic group, and we never escaped ethnicity. At least my generation didn't escape ethnicity. And that was compounded by the fact that a few people of my generation learned Hebrew at a level where they could do an interview on television or give a speech in Knesset. That was rare. The Hebrew was an important key to integration.

But with that, our American ethnicity, our American ethos, our American worldview, I think, had profound impact on many aspects of Israeli society. First of all, we brought our religious forms with us. We brought the reform movement and the conservative movement. We brought American Orthodoxy with us, and American feminism. We brought American activism. If you look at any Israeli political movement Americans are disproportionately represented. And we brought that activism. We brought a commitment to democracy, which I think reverberates to this day. Most of the Jews in this country came from the Middle East or from Eastern Europe and didn't have that tradition.

My generation came to a totally different country. You watched all this happen. Do you have a sense of what the contribution of that generation was? Was it similar? Was it different? Was the fact that they left a different America impactful on what they brought to Israel? What's your sense?

I think they built on the previous generation's accomplishments. Whether it be in the religious field, the academic field, the political field. I think you came to a country that was in transformation, transformation from being that lower middle class, largely agrarian society to being a highly socially and economically stratified but technologically robust country that was emerging from isolation in so many different ways. The Arab boycott was behind us. You could travel to China; you could travel to India. There was peace with Jordan and peace with Egypt. You had a strategic alliance with the United States. South America took place in the last couple of years.

But Israel was merging into something that looks more or less like what Israel looks like today for good and bad. Israel has a social gap, which is up there with the United States, Mexico, and Chile. That was not the case when I made Aliyah in the 70s. That's a big thing.

What I am seeing today with olim who come to this country are some want to come just want to be in the army and go home. And others when they come today, there's an expectation of getting a job in high- tech. There's actually an interesting phenomenon of this notion of aliyah to Tel Aviv, and there are thousands of young people in this city who have made Aliyah not out of a deep sense of commitment to Jewish history or identity, but because of a lifestyle choice. Tel Aviv has a great food scene, great beaches, great nightlife. The salaries in high tech aren't all that different than the high-tech salaries in the United States. So why not live here?

Why live here, though, if you're going to do high tech in the United States? They also have great food and some great beaches. In other words, I think you're right that they're not giving up a lot by moving from New York or San Francisco or wherever to Tel Aviv. But why are they coming? They're not making more money here.

It's fun. There's a better nightlife here. If you're a young woman here, there's almost no violent crime and you can walk around at night. And that is not what's going on in American cities. In San Francisco in particular you're not walking around as a young woman at night alone in San Francisco now. So, it's a lifestyle choice. And there are some interesting organizations that are operating to try to get people who have made aliyah to Tel Aviv to bring them into Judaism and remind them, “Hey, this is not just a fun surf and high- tech capital. There are other things going on here as well.” Our biggest challenge in the future is not going to be with the olim, it's going to be Israel's relationship with olim.

We had our challenges because we came from such a high socio-economic background, because we weren't chased out of the United States. We were the only group of olim that were greeted with skepticism and sometimes contempt by Israelis. If you weren't going to make Aliyah, they’d say, “Well, why don't you live here?” But if you do make Aliyah, they'd say, “Have you gone crazy? There had to be something wrong with you that you left the United States to come here. Today nobody says that. No one says you're crazy for leaving America. But the big problem today is that a large segment of the Israeli population no longer favors mass Aliyah. From anywhere.

When I was in government, we had a historic opportunity with the sharp rise of antisemitism in France to encourage aliyah. In fact, the majority of the French Jews who left France did not come here. They went to England, they went to Canada, they went to other places because to them Israel was unwelcoming. And I know that from inside, there was nobody in the Israeli government, and you're talking about a right-wing government, that was going to stand up and defend French Aliyah.

Why?

Because politically it is inexpedient. There are too many Jews here. It's too crowded. I hear this again and again and it used to behind closed doors, but now it's not even behind closed doors. You can't drive on the highways. The housing prices gets shot up by having more people demanding houses. They take our jobs. They come here expecting things. And Israelis say, “I need to pay my taxes for some wealthy Jew from Paris to give him benefits. Who needs that?”

And so, we're in this unique situation where Israel today is, on one hand, the largest Jewish community in the world. We're secure, we're strong. We're in many ways affluent. People that were sitting on the fence about making Aliyah are no longer sitting on the fence and they have decided to come. And this is happening at exactly the time that more and more Israelis don't want them to come.

And I believe that one of the responsibilities, I think the imperatives of Israeli governance is to reeducate the Israeli public about the moral and educational and economic benefits of Aliyah, because nothing has been more transferable to this country than the Russian Aliyah. I think that the question is really a social and psychological one. Do we still want them? Do we still think it is an essential part of our Zionist ethos to encourage and to welcome Aliya?

The American Jewish community is subject to historical processes that an overwhelming majority have nothing to do with the state of Israel. We didn't invent “woke-ism”, we didn't invent sensor culture. We didn't invent intersectionality. We didn't invent critical race theory. And yet we are often on the receiving end of many of these ideas. And our ability to counteract them is very limited. For a certain segment of very progressive American Jews, it's no longer about what Israel does it’s about who we are. And if we do something good, it'll be white washing or pink washing, whatever washing. We're about to have the largest gay parade in Asia and that will be called pink washing because everything Israel does that's good is inherently bad, because we're inherently bad. We could create a Palestinian state tomorrow and reduce Jerusalem and rip 400,000 settlers from their homes and it would not make any difference for these people.

But I'm actually optimistic about the future of American jewelry. First, a city like New York has had a positive Jewish growth rate for the last seven or eight years. Now, overwhelmingly, that's because of the Orthodox. But in my dealings with the Jewish Agency, I've been strongly recommending that we reach out as the Jewish Zionist state to the Haredim. I was the first ambassador to meet with the Haredi leadership of the United States. We must reach out to them. We should have a Haredi birthright program… I think there'd be a tremendous response to that. So, the American Jewish community in 20-30 years from now might be numerically smaller, but it'll be more Jewish, and it'll be more cohesive, and it will be more attached to the state of Israel. And we're seeing it right now, and we're seeing every year, the number of olim from the United States goes up, not down. Now, part of it is owned to antisemitism. And part of its owned to the technological miracle here and a great lifestyle. People come here because they're Jewishly committed, not necessarily Zionist committed, but they're Jewishly committed. So, I think this is a source for optimism if we know how to embrace these people and to talk their language.

Former Ambassador Oren recently finished a new novel, a literary mystery titled Swann’s War. The book will be published later this fall.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.