My mom used to tell me that she always remembered where she was when she heard that FDR had died. She was only ten, she would remind us, but she remembered. And she always would.

Depending on our age, most of us remember where we were, and maybe whom we were with, when we heard that war had broken out in 1973, or that the World Trade Center had been hit by two planes, or that the Challenger had exploded. I can still picture the bedspread on my parents’ bed where I was sitting as we were watching the black and white TV in their bedroom, hearing about the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

This weekend will probably rank with those. I didn’t hear until Shabbat afternoon. We’re off the grid on Shabbat, so it wasn’t until I was hanging around in the courtyard, waiting for Mincha to start on Shabbat afternoon, that I heard. We were hearing booms in the distance, and it wasn’t clear what they were. “Here we go again,” someone muttered, and someone else said (correctly in this instance) that it was nothing.

“But I wouldn’t be surprised if Nasrallah has some surprises awaiting us on Rosh Hashanah,” I said to a friend. He stared at me like I was nuts. “What?”, I asked. “He’s dead,” my friend said.

A lot of memories are bound up in that courtyard for me. It’s where we read Lamentations on Tisha B’Av in the summer of 2023, after the Knesset had started implementing the judicial reform, when adults I’d known for years literally burst into tears and sobbed. It was where we were sitting a few months later we heard lots of booms, booms that turned out to be very much the opposite of nothing. It was where, yesterday, I heard about Nasrallah. And it’s the courtyard at which most of our community last saw Hersh, at the evening’s Simchat Torah dancing, before he left to have dinner with his family and to go to a music festival.

I wouldn’t say that Mincha was jubilant, because Shabbat Minchah doesn’t quite lend itself to that, but there was a fresh breeze in the air. People were smiling—not silly, triumphalist or gloating smiles, but a kind of “maybe we’re becoming ourselves again” smiles.

As soon as Shabbat was over, less than an hour later, we obviously turned on our phones and the TV. The memes, because this is Israel, were already very much out there. This one was everywhere on WhatsApp.

The Hebrew עזב את הקבוצה, azav et ha-kevutzah, means “has left the group.”

Cute.

It went way beyond the cute, though. Even though Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari—the IDF spokesman who’s become the face of this war for Israelis—had announced Nasrallah’s death hours earlier, the post-Shabbat evening news replayed the announcement.

And as all the panelists (see them in the photo below) noted, he was smiling. Barely, not widely. But he was smiling. Not gloating. Just smiling, the way a person who’s given his entire life to this country (he was commander of the special ops unit Flotilla 13—our Navy Seals—among many other roles) smiles when the army he’d long been part of was finally starting to do what it had been known for. “Never, ever seen that guy smile before,” more than one panelist noted.

The table around which the above-mentioned panelists were seated (below) had an image on it. Does it usually? I couldn’t remember, despite the hundreds of hours I’ve spent staring at people around that table since October 7. But there he was, Hassan Nasrallah, with the symbol of a target next to his head.

No, not quite celebration, but a deep, deep sense of satisfaction and relief.

And then, something I’d never seen. In the shot below (these are all old-fashioned photos of a real TV with an iPhone), what are all those bizarre red paper cups doing on the table? Amit Segal, the newscaster on the left, was pouring a second round of Arak (see the bottle in the red circle), this time to include Dan Halutz (in the blue shirt on the right), who had once been the IDF Chief of Staff and the Commander of the Air Force, and had just joined the group to give his assessment of what all this meant.

Here’s a Zoom-in so you can witness Amit Segal’s bartending abilities with greater clarity.

I wasn’t so sure how I felt about that lechayim on the news, but we’re in uncharted waters.

It’s much bigger than just Nasrallah, of course. A lot of people I was with today mentioned Jared Kushner’s tweet on the subject.

Kushner made the obviously correct point. Hezbollah “was” the mullahs’ insurance policy that we wouldn’t attack Iran, because if we did, Hezbollah would send thousands of missiles flying our way. But what if there’s eventually no Hezbollah? What, then, happens with Iran?

It’s possible that a new “morning has broken” in the Middle East. This is still far, far from over, but there’s a bounce in people’s steps—we’ve waited for something significantly good like this for a long, long time.

But …. what about October 7th?

September 27 may one day be seen as a turning point in this war—we won’t know for a while. But what we already do know is that October 7 was a turning point in Jewish history. Jewish history will never, ever be the same. Not in Israel, not in the Diaspora. Something changed dramatically. What it is, exactly, we’re still trying to understand and it might still be changing.

But October 7 will always be a more important date than September 27.

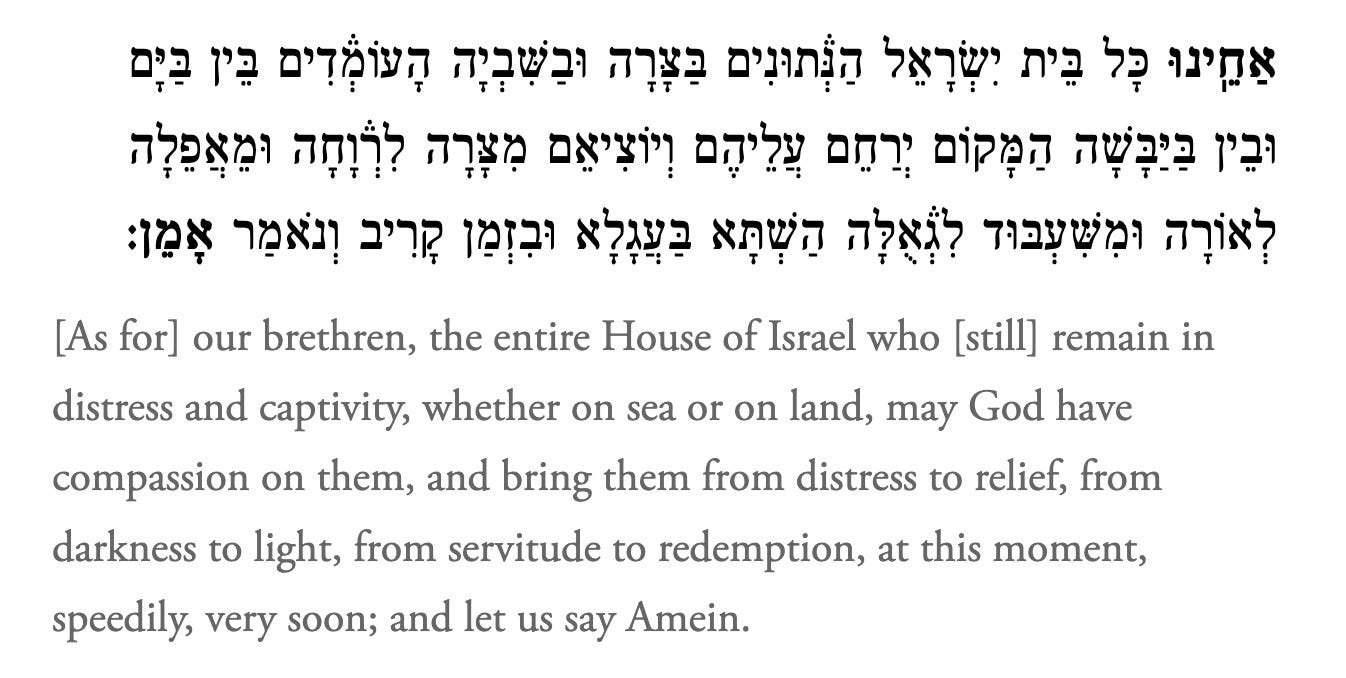

And we need to remember that, because (among many other reasons) September 27 is over, and October 7 is not. There are still 101 hostages being held in conditions too horrific to imagine, and we’re coming up on a year. How many are alive? We don’t know. But we do know that they are there because we failed them on October 7, and that we have continued to fail (perhaps despite our best efforts, depending on whom you ask) to get them back.

October 7 is still ongoing because the broken, shattered families are still broken and shattered. Because the children who were traumatized that day will forever be traumatized, and they and their emotional scars will be part of the fabric of the society that is Israel for longer than anyone reading this will be alive. October 7 is still ongoing because the terror that Israeli parents feel sending their daughters and their sons to war has always been there, but is now part of social discourse in a way that I don’t remember it ever having been. October 7 is still going on because the people who got us into it are still running the country, because the widows and the orphans and the amputees are always going to be part of the soul of the new Israel.

Our challenge this week and beyond, despite the successes of this weekend, is so try to reclaim some of the shock and horror and emptiness that we felt a year ago— because the Israel that was lost and the souls that were taken are still gone, and because working hard to remember searing pain is part of what makes our people who we are.

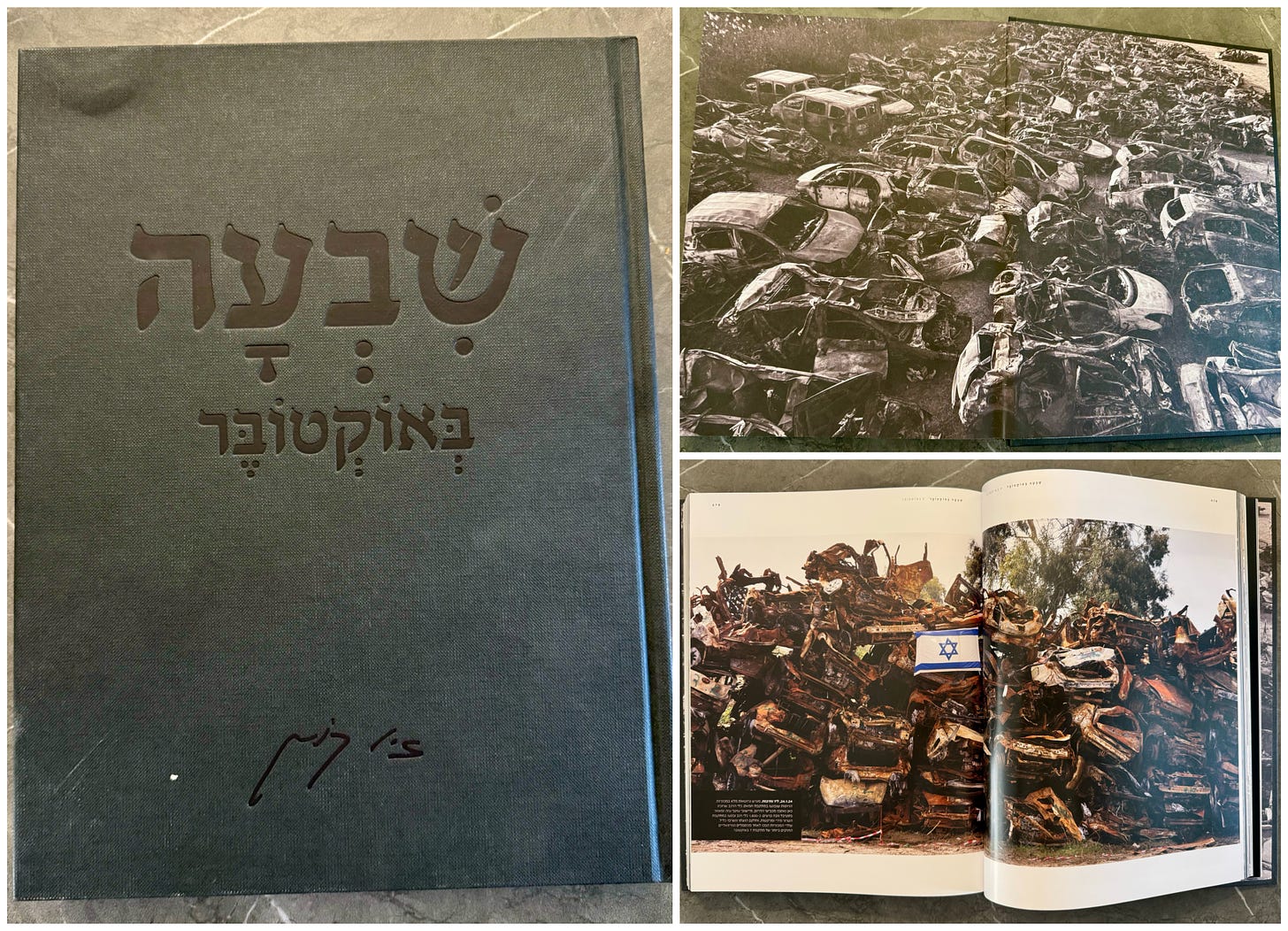

I’m told (as I mentioned last week) that at least 80 books have been published in Hebrew in Israel about October 7. One is this thick coffee table book, with essays and many photographs taken by the well known Israeli photographer, Ziv Koren (book is here on his website). The book is called SHIVA Be-October. SHIVA for “seven” and SHIVA for, well, “shiva.”

It’s a beautifully made and heavy book, but you don’t know how heavy until you open the front cover and get to the black and white photograph on the inside. Or pages later when you get to a color version.

It’s not a pile of cars. In most of those cars, people were shot, or burned. Murdered or kidnapped. In every single one of those cars, people were terrified and wept as they’d never wept before.

The cars are by now all piled up but the loss is hardly so neat. What happened on that day will color this country—and should color this country—as long as any of us will know.

Rosh Hashanah is called Yom Hazikaron in classical sources, “The Day of Remembrance.” Despite recent successes, we need to force ourselves to remember.

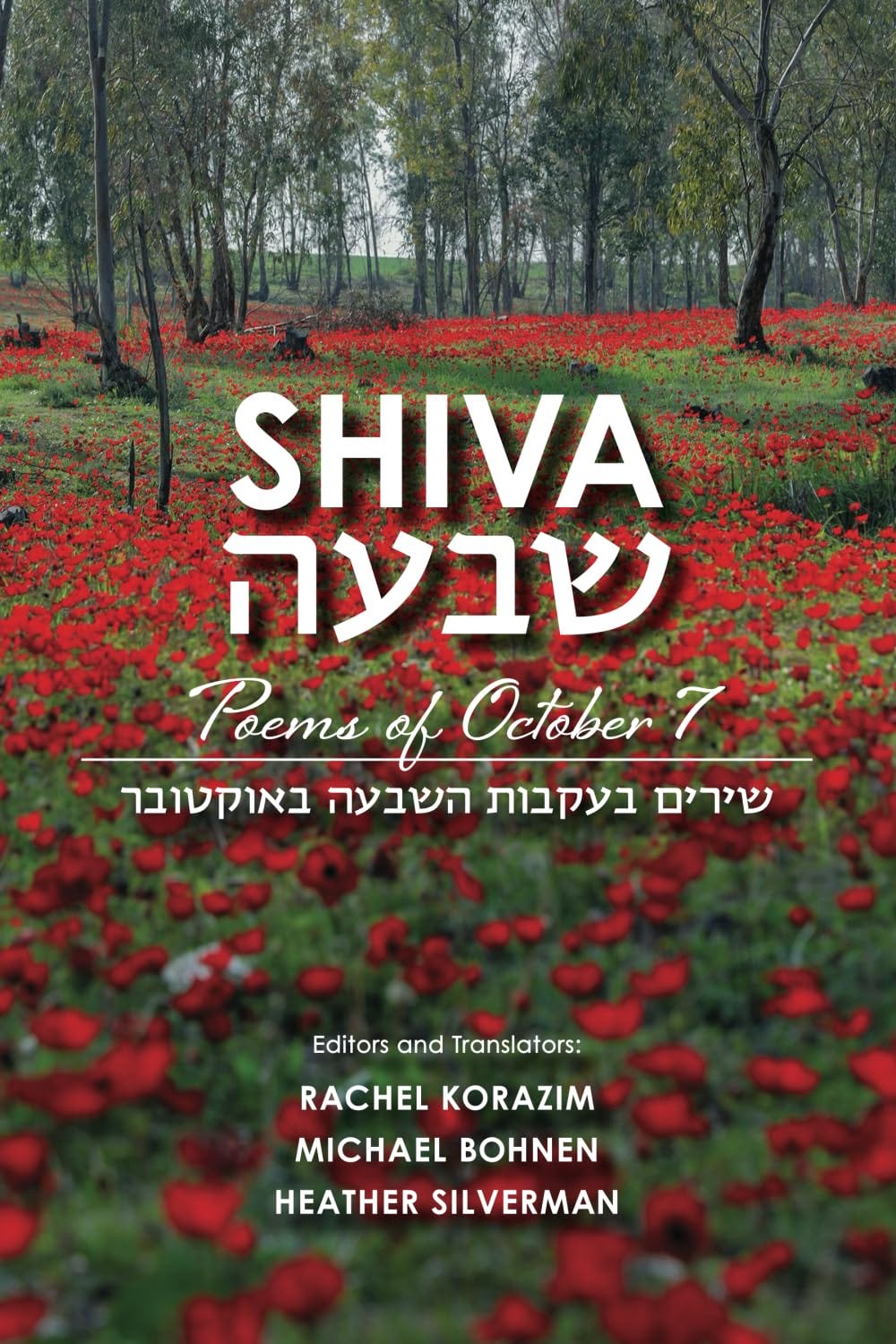

Which brings me back to a different book, the book of poetry I mentioned last week, that you can still order to have on time for Rosh Hashanah.

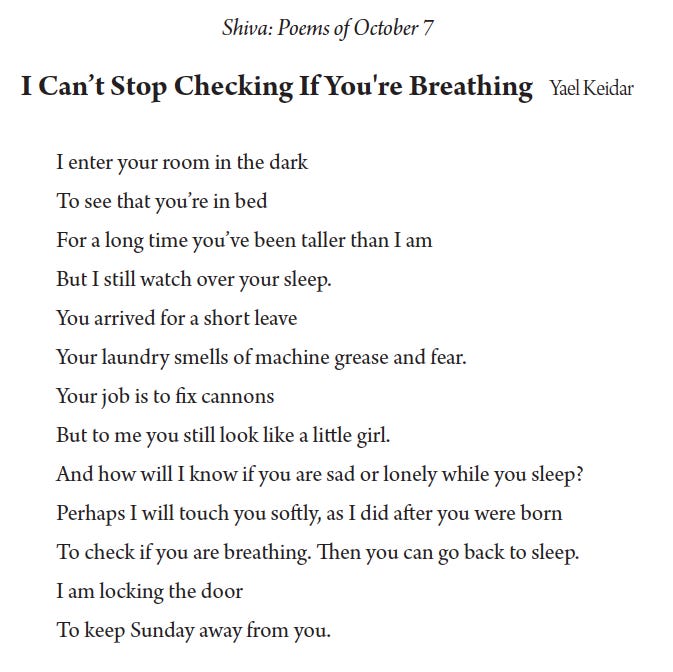

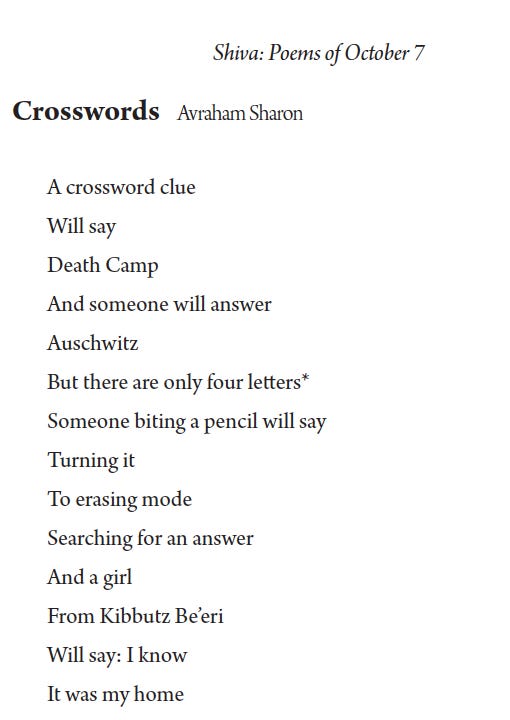

This book, too, is called SHIVA. Not SHIVA Be-October, but SHIVA: Poems of October 7. They appear in Hebrew and in English, and on a website there’s a mini class by the very gifted Rachel Korazim about each poem. (The poems are posted here with permission.)

I’ve chosen a few of the simpler, shorter ones for here (none are very long) to give you an idea of what a few choice words can do to (re)shape our memory, our mood—and yes, our conversations around the holiday table.

I don’t want to talk about Hassan Nasrallah at our Rosh Hashanah table. He’s dead, and by next Rosh Hashanah, we’ll have other challenges. I don’t want to talk about politics, either, because next they’ll either be the same (which would be very bad) or different (which might or not might be good or bad). I want to talk about this country, its soul, its heart. I want to think about Jewish hearts, and Jewish souls. Jewish yearnings, Jewish prayers. Jewish memory.

And we’re going to do that by speaking about a few of the poems in this book (I’m still deliberating which). It’s the simplest thing in the world to do …

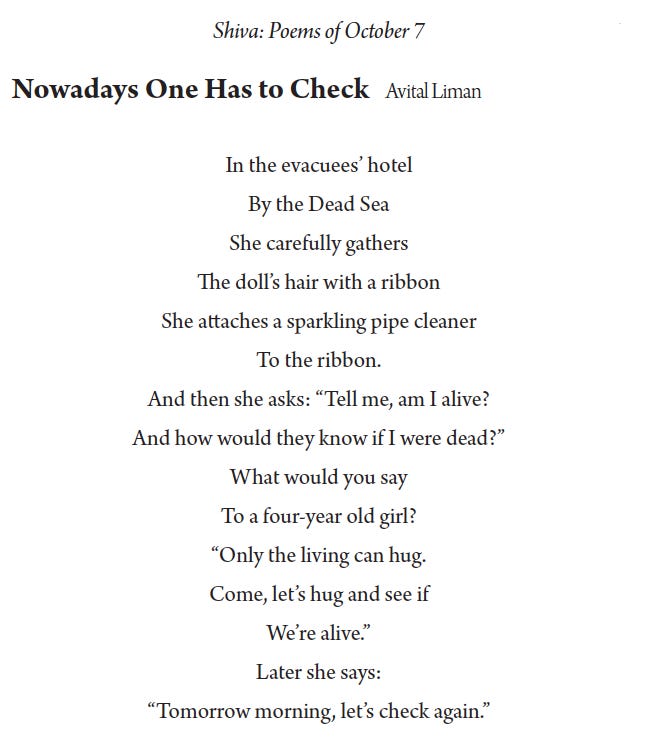

The stories we hear about what young kids still remember about that day, about their fathers and mother disappearing off to war for months, about running to the shelter time and time and time again … are still harrowing, almost a year later. This image of the little girl who’ll need to check again tomorrow if she’s really alive captures not just what little girls and boys are feeling—they speak for a country that wants to make sure it’s still alive.

We also have a kid who could get called back up. We also would do anything we could to “lock the door” to keep Sunday (they day they normally go back to base) away. But we can’t. To be a parent in this country is to be largely powerless, to live with dread, to pray that this ends OK—for all of them, for every single one of them. The mom in this poem is, like the little girl above, speaking not for herself, but for all of us.

“It was my home.” So many places here “were our home.” So many people here used to be part of our homes. A lot remains, but so much is gone.

Things will get better, I hope and pray, but Jews have never welcomed the dawning of a brighter day by forgetting the darkness of the ongoing past. With a few simple poems, we can be part of continuing that.

With wishes for shared memories, and for a better year ahead.

"Morning has broken" — but we dare not forget the night