Not always successful, and sometimes violent —a brief history of Israeli protests (Part I)

With judicial reform about to start again, we look at how protests have and have not worked in Israel's past. We start with Menachem Begin's protests against German reparations in 1952.

Pesach is behind us, as are the “national holidays.” The Knesset returned from recess and got right into the budget, which it needed to pass in order not to have the government automatically dissolved. There was never really any genuine doubt that Bibi would get the budget through, and this week, he did.

What’s next? Says the PM, it’s now time to press on with judicial reform. Does he really mean that? Did he not notice what happened to his polling numbers (which went up a bit as a result of our little war with Gaza) because of the proposed reforms? Is he encouraged by the slowly declining numbers of protesters? It’s hard to know what he’s thinking, given that intersections between what he says and the truth are coincidental at best (even his closest colleagues acknowledge that openly).

The opposition is warning Bibi not to go back to that volatile place. “I want to remind Netanyahu that stupidity is repeating the same action and expecting different results,” said Benny Gantz as soon as Bibi announced his intentions. “If the judicial coup resumes, we'll shake the country and bring it to a halt.”

If Netanyahu is serious, be prepared for the number of protesters to rise sharply, and for the rhetoric to become more heated as the tactics become more brazen. Where that will lead, it’s hard to say, though the smart money is on—at most—very limited judicial reform.

These are not Israel’s first protests, and in order to understand what’s unfolding now in the context of Israeli history, we’re going to offer a brief review of some of the major protests that have shaken the nation.

This week, we start with the protests that Menachem Begin led against the idea of German reparations in 1952. Then, like today, it was not an issue of which side had principles and which did not. Both did. What lay between them, as is the case today, was a radically different version of what the Jewish State should be.

David Ben-Gurion was so intent on saving Israel from imminent economic collapse that he was determined to get money from the Germans as reparations for the Holocaust. When he was told that Israel was not eligible for reparations for it had not been at war with Germany, Tom Segev relates in his biography of Ben-Gurion, the PM suggested that Israel should therefore declare war on Germany.

That, obviously, did not happen.

Ben-Gurion understood how contentious taking money for exterminated Jews from the exterminators would be, but argued that international admiration would come with an economically flourishing Jewish state; Menachem Begin, however, insisted that the Jewish state would lose all respect it had painstakingly acquired if Israel—the international face of the Jewish people—now took money from its former oppressors.1

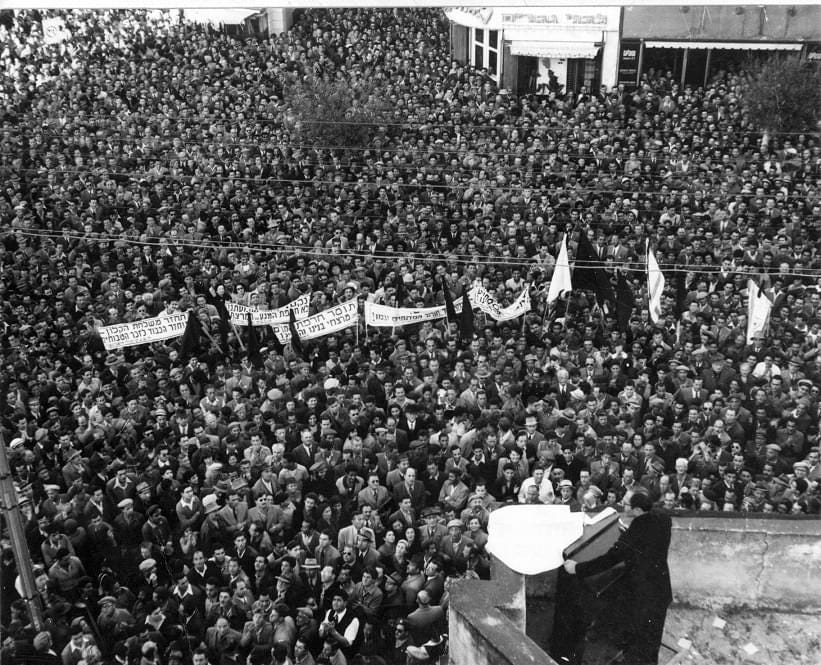

By early 1952, Begin was so thoroughly consumed by the reparations issues that he swallowed his pride and for the first time since he had quit political life in August 1951, he appeared in public on January 5, 1952, in Mugrabi Square in Tel Aviv, before some 10,000 supporters. Some of those in the crowd were carrying Torah scrolls, and Begin himself donned a black kippah, undoubtedly to make clear that this was no mere political issue. At stake was the dignity of the entire Jewish people; this was a matter not of politics, but of sanctity.

Always inclined to biblical metaphors, Begin evoked the memory of Amalek, the nation that had sought to destroy the Israelis in the desert by preying on the weak. In his address, Germany, like Amalek, was pure evil. The Torah commanded the Jewish people to obliterate the very memory of Amalek; thus, the last thing the Jewish state ought to be considering now was a financial agreement with Germany.

On January 6, Ben-Gurion announced the government’s intentions to open the debate on accepting reparations from Germany. The acrimonious national dispute reached its climax on January 7, the day the Knesset was scheduled to vote on the issue. Tens of thousands of people from all over Israel had gathered in Jerusalem’s Zion Square to protest the debate in the Knesset, then housed only a hundred yards away on King George Street. On a cold and rainy day, Begin addressed his listeners before walking down the street to the Knesset:

The most shameful event that has ever occurred in the history of our people is about to take place this evening. At this bitter hour, we will recall our hallowed fathers, our slaughtered mothers, and our babies who were led by the millions to the slaughter at the hands of the Satan who emerged from the very bottom of hell to annihilate the remnant of our people.

With that, Begin reminded his listeners of the enormity of the Holocaust in their national narrative. Yes, Ben-Gurion and the Israeli-born sabras might want to move beyond the Holocaust, but both the horror and the recovery were necessary parts of the Jewish people’s story. Begin continued:

They are on the verge of signing an accord with Germany and of saying that Germany is a nation, and not what it is: a pack of wolves whose fangs devoured and consumed our people, [and] even though that blood was spilled like water, it was not for naught. It gave us the strength to rise up against the British enslaver. Because we always asked ourselves how we were better than our slaughtered forefathers, and why they are dead and we alive. That blood, the holy and sanctified [blood], taught us to fight and lead us onto the enemy’s battlefield. And it is thanks to that blood that Ben-Gurion, that little tyrant and big maniac, became prime minister…

And then the man who had helped avert civil war in July 1948 in the Altalena incident (which we wrote about in a column called “No Civil War with the Enemy at our Gates”) seemed to threaten it: “There will not be negotiations with Germany, for this we are all willing to give our lives. It is better to die than transgress this. There is no sacrifice that we won’t make to suppress this initiative.”

Calling attention to the armed police presence, Begin declared his willingness, and that of his supporters, to die for their cause. He then dissolved the distinction between negotiating with Germans and becoming a Nazi: Mr. Ben-Gurion has sent policemen here carrying—according to information we have just received—grenades and tear gas made in Germany, the same gases that choked our fathers; he has jails and concentration camps. Ben-Gurion is indeed older than I am, and I am more experienced in standing up to a wicked government. And therefore I am announcing: Evil is standing before a just cause—and it will shatter like glass against a rock … You will collect taxes by force, services by force, nothing will be given [to the state] by our own free will. We will not have enough prisons to hold the protesters. Ben-Gurion’s police were the Gestapo. Ben-Gurion’s prisons were the despised camps of old. In a warning that was to haunt him for the rest of his life, Begin referred back to his decision to lay down arms during the Altalena incident, a decision of which he remained proud:

When you fired your cannon on me [during the Altalena episode,] I gave the order “no!” Today I will give the order “yes!”…You will no longer be a Jewish government, and you will not have moral legitimacy in Israel.

It may have been a cri de coeur blurted out in the passion of the moment. It may have been an intentional threat with no intent to follow through. And it may have been a genuine warning. We cannot know. But Begin’s threat—moments before the Knesset debate was to begin—to resort to armed resistance against Ben-Gurion would lead opponents to argue that the “real” Begin was the hunted “terrorist” from his Etzel days, animated by antidemocratic impulses.

But Begin was unrepentant. The State of Israel was but four years old, and what he wanted to know was whether it had a soul. This was his Jewish version of “give me liberty or give me death.” Life itself was not an ultimate goal; life was worthwhile only if the Jews who had narrowly escaped extinction still stood for something. At 5:30 in the afternoon, Begin completed his speech and strode the short distance up the street toward the Knesset building to take part in the deliberations. Hundreds of those gathered in the square followed him. Despite their best efforts, the police were unable to block the protesters from reaching the Knesset and they eventually fired their tear gas.

Inside, Begin was in the process of being sworn into office (this was his first official appearance since his departure from public life). But outside the building, matters grew more ominous as his supporters surrounded the Knesset. Amid the yelling and the cacophony from the clashes raging outside, Begin took the podium. He dismissed out of hand the government’s contention that these Germans with which it would be negotiating were different Germans from those who had carried out the Final Solution:

Maybe you will say that the Adenauer government is a new German government, that they are not Nazis? You probably know Adenauer, [so] I ask: In which concentration camp was he interned when Hitler was governing Germany, to which prison was he sent because of the bloodthirsty rule of the Nazis?…I will remind you of some facts: Sixteen million Germans voted for Hitler before he came to power. There were twelve million Communists and Social Democrats in Germany. To where did they disappear? The German army had twelve million soldiers, the Gestapo millions, the S.A. and the S.S. millions. To where did they disappear? From a Jewish perspective there is not one German who is not a Nazi, and there is not one German who is not a murderer. And it is to them that you will go get money?

Meanwhile, outside, the rioters whom Begin had riled up with his powerful oratory hours earlier were now throwing rocks at the Knesset building, attempting to break into the hall. A volley of stones soon broke through the windows, interrupting Begin’s speech. MK Hanan Rubin was hit in the head. The tear gas the police had used now filtered into the debate hall. Through the broken glass of the now shattered windows, the MKs could see cars outside going up in flames.

Begin nevertheless continued, now addressing Ben-Gurion directly:

I am turning to you not as an adversary against an adversary; as adversaries there is a chasm between us, there is no bridge, there cannot be a bridge, it is a chasm formed in blood. I am turning to you in the final moment as a Jew to a fellow Jew, as a son to an orphaned nation, as a son to a bereaved nation: Stop, don’t do this!

Ben-Gurion, of course, was entirely unswayed by Begin’s speech. This was, after all, the same Ben-Gurion who had told the Knesset during the Altalena deliberations that he would sink the ship even if it sailed back into international waters. He surely never even considered taking Begin’s arguments seriously. Instead, referring to the throng outside, he asked, “And who brought these hooligans here?” That was too much for Begin, who countered angrily, “You are the hooligan!”

But as far as the Speaker of the Knesset was concerned, Begin had now crossed a red line. He demanded that Begin apologize for insulting the prime minister, or he would be removed from the podium. Begin, not surprisingly, refused to stand down, insisting that if he “won’t speak, then nobody will speak here.” At 6:45 p.m., scarcely an hour after Begin’s return to politics, his speech had brought the Knesset plenum’s debate to an utter halt. The army was called in to restore order, and precisely as Begin had predicted in Zion Square, some 140 protesters were arrested. Hundreds of injured policemen and protesters had to be taken to hospitals.

It was not until 9:00 p.m. that Begin agreed to publicly apologize to Ben-Gurion.

As is the case now, in the spring of 2023, that deep division was not a matter of those with principles versus those without. The two men, beyond even their personal enmity, simply saw the Jewish world through profoundly different lenses. For Ben-Gurion, the Jewish state was about looking forward, acknowledging the horrors of the European past but moving beyond it. Ben-Gurion harbored no romantic memory for the Jewish world that had been lost. It was time, he believed, to jettison completely that European model of what a Jew had been, and to replace it with a vigorous and—if reparations could be passed—economically self-sufficient Israeli.

Begin could not have been more different. He was a product of a traditional father he revered, and of the religious schools—the cheder and the yeshiva—as well as secular institutions. Although he certainly did not romanticize the Diaspora experience, he could never disparage all that it had been, either. Begin had lived longer in Poland than Ben-Gurion had, and in worse times, and he had overseen a militant Jewish organization there. Begin was no less committed to the Jewish future, but for him, the past animated the future. Whatever strength Israel might eventually muster, it would do so because the Jewish past would forever remind Jews of why they needed a state. And just as he believed that the Jewish past was more heroic, so he believed the Jewish future would not be exempt from ancient enmities.

More religious than Ben-Gurion, by both temperament and training, he was also far less messianic. Murderous anti-Semites were the villains, and there was no point blaming the Jews for the “shame” of studying in a yeshiva. Begin rejected the impotent Jew of the Diaspora no less forcefully than Ben-Gurion did; it was he, after all, not Ben-Gurion, who had called for the revolt against the British. But Begin—like the Sephardic Jews and religious Zionists who would one day form the backbone of his political party—could not imagine and would never accept a Jewish narrative in which all that Jewish Europe and the Sephardic Diaspora had accomplished was derided.

They never settled their differences on this matter. But the violence was over, soon, too, was the debate. On January 9, the Knesset voted 60–51 to proceed with the negotiations with Germany.

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Much of this account is based on my book Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel's Soul.

The two situations don’t seem at all comparable. Either reparations were so morally unacceptable that none could be taken, or Israel’s needs were great and reparations were a minimal way of redressing the great evil naziism had inflicted that more than justified their use. Either they could be taken or not. Nor did the opponents threaten to undermine Israel by hampering its functioning.

But, in this case ,compromise is possible. There are any number of variable ways in which the current unfettered judiciary could be limited. There is plenty of room for negotiation, and a willingness to utterly halt the basic operations of one’s country in order to prohibit any iota of change in the status quo doesn’t speak well for those promoting that position

A feature of the Israeli protests that immediately catches the eye is that everyone comes out with the same flags. Is this a legal restriction or a manifestation of patriotism?