Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

Of prison breaks, then and now

The uncanny similarities between last week's Gilboa Prison fiasco and the now mostly forgotten 1947 Acre Prison Break that Menachem Begin launched

History is not linear, of course. If anything, it’s more of a spiral. Things have a way of repeating themselves, albeit in tellingly different forms, so that those who know about the earlier incidents can appreciate the newer ones with much greater depth. The disaster in Afghanistan resonates differently if you remember, as does my generation, that last helicopter taking off from Saigon. The loss in Afghanistan resonates differently if you know how Vietnam unfolded and ended, and what transpired in Korea before that.

The same is true of the jailbreak from the Gilboa prison last week, in which six terrorists (some jailed for murder, some serving life sentences) escaped from prison under the nose of Israel’s hapless guards. What has shaken the country more than anything is the colossal list of mistakes that the utterly inept Prison Services—who are being portrayed in Israeli media these days as more or less Keystone Kops—made. It would be laughable were it not so alarming.

Here’s a sampling:

The prison was built on a foundation of posts that left large voids underneath, large enough to crawl through. Then the plans were posted online by the architectural firm that designed the prison.

The prisoners still had to dig from the end of the pre-existing spaces to their exit, which they did for many months, undetected.

Some of the prisoners hailed from Jenin, but were nonetheless jailed at the Gilboa Prison, almost in their backyard, where they knew the terrain and were more likely to receive help from locals.

Zakaria Zubeidi, the worst of the bad guys, is from Fatah, but asked suddenly to be housed in the same cell with the Islamic Jihad prisoners … an unusual request, to say the least. But his request apparently raised no eyebrows and was immediately approved (they escaped almost immediately thereafter).

The prison did not have a single vehicle available for pursuing the escapees.

It took several hours from the time a citizen reported suspicious people crossing a highway until the prison could confirm that the six were on the loose. For a while, they believed that only three were gone.

The guard tower that faced the direction from which the terrorists dug up to the surface from their tunnel had been unmanned for months, apparently because of budget cutbacks.

The guard who was on duty was fast asleep at her post as they escaped.

The pathetic list goes on …

All this comes on the heels of the tragic death of a Border Guard officer, 21-year-old Barel Shmueli, who was shot in the head at point blank range a few weeks ago by a Gazan protester, who apparently remains unidentified. Numerous mistakes were made by the commanders who placed him there, but somewhat shockingly, the brass has come to their defense even while acknowledging the catastrophic missteps. (“If you keep accusing your army, it won’t fight for you.”) Why? His parents’ very unusual reaction (which we’ll write about) and the IDF’s response say a great deal about shifting sensibilities about the army in this country, attitudes which are rarely covered abroad.

Shmueli’s tragic and needless death, of course, comes on the heels of the May 2021 conflict with Hamas, which Israel, once again, was unable to win decisively. Depending on how one views the Yom Kippur War (Israeli experts’ assessments vary), it’s been either since 1973, or more likely, since 1967, that Israel has won a war hands-down. Not an auspicious thought, when you consider that the day of reckoning with Iran may be growing closer.

What all this means for Israelis’ view of the once venerated IDF and what it means for Israeli society is the subject of a column soon to follow.

But back to our “spiral” view of history. When the prisoners’ escape was first announced, Hamas hailed it as a “great heroic act.” Observers from afar might have chuckled. But for those who know the story of the Acre Prison Break of 1947, it was clear that once again, Palestinian resistance was simply taking a page from Zionist history.

Here, then, a brief reprise of that much older story.1

The Acre Prison, like the Bastille centuries earlier, was more than a prison. It was was a symbol of British imperial power—the Crown’s freedom to arrest suspects at will, hold them indefinitely, convict them, and, when it saw fit, execute them. Housed in a seemingly impregnable Crusader-era fortress (the Crusaders, apparently, were more methodical builders than the Israelis), it held many of Menachem Begin’s fighters, members of the illegal paramilitary underground group, the Eztel (acronym for Irgun Tzva’i Leumi, or “The National Military Organization”), who had been captured over the course of numerous previous operations. Begin was determined to get them out, because he needed them for the ongoing fight to dislodge the British (the same hope that many Palestinians today have regarding Israelis, of course), he wanted to make sure that they would not be executed, and because an attack on the highly defended prison would prove horribly demoralizing to the British.

Sound familiar?

Forty-one prisoners were selected for liberation; thirty were Etzel members and eleven were from the Lechi (another illegal paramilitary group, this one headed by Yiztchak Shamir, who, like Begin, would also eventually become Prime Minister). On May 4, 1947, the Etzel conducted one of its most daring operations and broke into Acre Prison.

At a prearranged signal, Etzel fighters outside detonated the explosives, creating a breach in the wall. The prisoners inside blew up internal heavy iron bars using explosives that had been smuggled in earlier. A battle erupted in the prison courtyard, but the prisoners marked for release made it out. They boarded prepared trucks and sped off. British police followed in hot pursuit, but were impeded by the mines the Etzel had placed along the road in anticipation of the chase.

Yet precisely as Zakaria Zubeidi and his fellow Palestinian fugitives discovered this week, getting out of prison is rarely the end of the story. (I trust that it’s patently obvious that my reflecting on similarities in the operations should in no way be construed as moral equivalence—quite the contrary).

The Etzel planners did not anticipate that British soldiers would be bathing on the coast south of Acre. Hearing the commotion, the soldiers dressed quickly, gathered their arms, and set up a roadblock. A skirmish ensued, and nine Jewish fighters were killed—seven from the Etzel, including one who had been saved from the gallows less than a year earlier, and two from the Lechi.

In the end, the Etzel successfully freed twenty-seven of the forty-one prisoners it had originally designated for liberation; six of the prisoners died in the battle, and eight others were wounded and recaptured by the British. In the confusion, more than two hundred Arab prisoners (the majority of the Arab prisoners in the jail) also escaped.

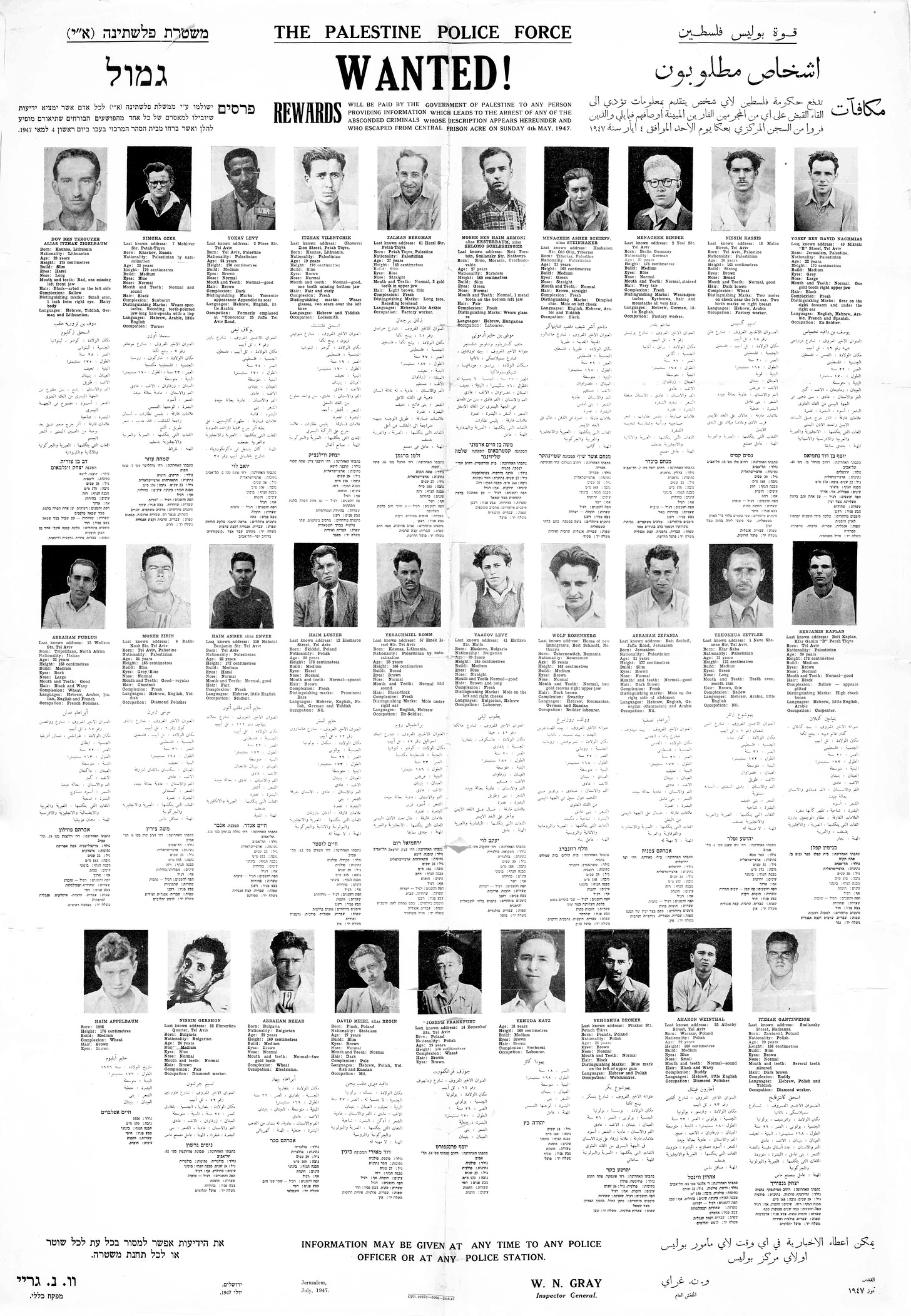

(You can see the “Wanted” poster that the British distributed, above at the very top of this column. The one that Israel released last week is here:)

But that disastrous and unexpected skirmish was not the end of the bad news. Another major element of the plan went wrong. Three Eztel men, who had been standing watch over one of the Etzel posts, did not hear the signal to board the truck and got left behind. After a lengthy fight, they were captured by the British, tried, and sentenced to death by hanging. Begin knew that having been humiliated, the British were likely not to back down on executing these men. He would not appeal to the Crown, which he considered an illegitimate occupier of Palestine (sound familiar?), but he did turn to UNSCOP (the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine), which he was certain would do no good.

So he took even more radical steps, which like the Prison Break itself, soon spun out of control. Begin instructed his men to kidnap more British officers, so that they could then be traded for the Etzel fighters. But that, too, got terribly complicated, and what would follow would be known as the Sergeants Affair, which even Begin himself admitted led to was the most morally dubious decision of his entire life.

I’ll post a summary of that episode for subscribers tomorrow, along with the second installment of the Matti Friedman podcast.

That, in turn, led to huge tensions in the yishuv, a vicious outbreak of anti-Semitic violence in England, and did great damage to Begin’s reputation ….

One never knows where a prison-break will end, and with the Gaza cease-fire fraying in response to the escape, we don’t know where this one will lead, either. Nor do we know, yet, how and whether Israel will find the last two terrorists still on the loose. Or what that will unleash.

Plus ça change has never been truer.

It was when Shabbat ended a few days ago and we turned on our phones to check the news that we first heard that four of the six fugitives had been nabbed. After reading the stories for a bit, I was curious what the New York Times might have to say about that.

After all, this was a fascinating story. First, Israel had found them. Second, Israel could easily have found a way to kill them in the process, but thankfully didn’t. They are all alive and well (though likely to have far less pleasant prison stays for the next few decades). Third, it’s become clear that both of the nabbed pairs were found because the Israeli Arab towns to which they went did not offer assistance, and because of tips phoned in by Israeli Arabs, admirable acts of loyalty to Israel. That’s a significant development in and of itself.

So what did the NYTimes have to say about Israel on its online front page? Only this. Really, only this. No other mention of Israel on the online front page. (Had we found them and killed them in a hail of bullets in a shootout, which would actually have been much less surprising than what did happen, does anyone have any doubt that it would have gotten coverage?)

(You can see the full NYT online front page below, at the very bottom of this column.)

So, while Israeli Jews and Arabs came together to catch murderers without a shot being fired, all the NYT online front page had to say about Israel was something about the destruction of the Second Temple being a “warning in a deeply divided country.”

Some pathologies, obviously, are incurable.

In one scene from Matti Friedman’s fascinating three-part documentary series on the Lebanon War that he did for Kan TV, he shows a jeep full of young soldiers. At this point in the series, it is already obvious that the Lebanon War is an unfolding disaster, that the brass is lying to the government, that the government is lying to the people and that Israel is hopelessly mired.

But the soldiers in this jeep are undeterred. Brimming with optimism, one of them says, with unbounded passion, that they are in Lebanon to protect the State of Israel, and will do what they are told to do, endure what they must.

His face is unmistakable. That young soldier is Naftali Bennett. The mere fact that Friedman found that clip is astounding. As Matti makes clear in our discussion, Naftali Bennett is a first in many ways—the first religious Prime Minister (no, Menachem Begin was not), the first to have been elected on the strength of an Arab party in the coalition, and, often overlooked, the first Prime Minister who came of age not in Israel’s earlier (and successful) conventional wars, but in the failed Lebanon War. That, suggests Friedman, has enormous implications for how Bennett and his generation see Israel and our region.

In his fascinating comments in this episode, Friedman reflects on the Lebanon War, his service in it, his book Pumpkin Flowers which is based on that service, and then reflects on his next book, about a concert that Leonard Cohen performed for Israeli soldiers during the Yom Kippur War … and what the concert meant—and didn’t mean—to Cohen, the soldiers and the country.

We’re making an excerpt of that conversation available to everyone here, and tomorrow, we’ll post the entire podcast for subscribers (on Tuesday this week rather than the usual Wednesday, due to Yom Kippur).

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

The full NYTimes online front page, as promised above:

Much of this material based on the account in my biography of Begin entitled Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul.