Discover more from Israel from the Inside with Daniel Gordis

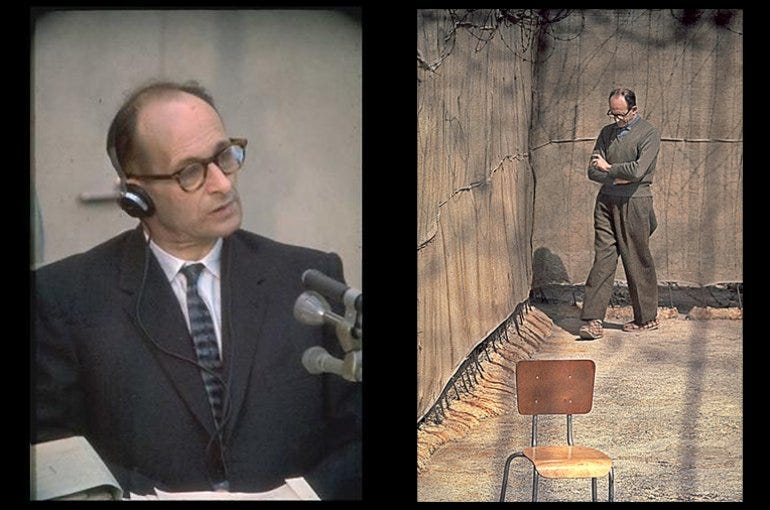

The capture of Adolf Eichmann

Today is the anniversary of Ben-Gurion's earth-shattering announcement

At four o’clock in the afternoon on May 23, 1960, the plenum of Israel’s parliament was packed with members of the Knesset, public observers, and just about anyone who could find a seat in the crowded hall. Rumors had circulated that Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion had unprecedented news to relay. As the assembled crowd waited for him to speak, the feeling in the chamber was electric.1

Ben-Gurion approached the podium and began:

I have to inform the Knesset that a short time ago one of the great Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, the man responsible together with the Nazi leaders for what they called the Final Solution, which is the annihilation of six million European Jews, was discovered by the Israel security services. Adolf Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will be placed on trial shortly under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators.

With that, Ben-Gurion walked away from the podium and departed the chamber. The hall was silent. Each person in the room struggled with the enormity of the announcement and its implications. Would the State of Israel finally exact even a modicum of justice from one of the architects of the annihilation of European Jewry? Would some measure of retribution finally be found for the millions of defenseless Jews murdered and tortured, gassed and burned or buried alive, and the million Jewish children whose lives had been cut off by the Nazi genocidal machine? Would there be an accounting for the sisters and brothers, parents and spouses, of many of those who sat in the room and of thousands of other Israelis?

Adolf Eichmann had been a Nazi SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) and one of the architects of the Holocaust, a central figure at the Wannsee Conference from which the idea of a “Final Solution” emerged. At the time of his capture, Eichmann was the highest-ranking Nazi official still alive. He had spent most of his time after the war hiding in Argentina, living under a pseudonym. Yet the Mossad, one of Israel’s security agencies, had managed to locate and capture him; it then secreted him out of Argentina and into Israel. Finally, it seemed, one of the archenemies of the Jewish people was about to pay for his crimes. Because the Jews had a state, their enemies had no refuge. Now those who sought to destroy the Jews would be held accountable.

Spontaneously, those in the hall shattered the silence and shook the chamber with thunderous applause.

PREDICTABLY, MUCH OF THE WORLD did not applaud. Condemnations poured in from around the globe. Argentinean officials, who unabashedly gave Nazis refuge, claimed that Israel’s action was “typical of the methods used by a regime completely and universally condemned.” The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 132, stating that Israel had violated Argentina’s sovereignty and warned that future similar actions could undermine international peace. The United States, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union all joined in condemning Israel. Argentinean civilians, following the lead of their government’s reaction, responded with violent anti-Semitic attacks on the Argentine Jewish community. Both the Washington Post and the New York Post published condemnations, while the Christian Science Monitor said that Israel’s decision to “adjudicate crimes against Jews committed outside of Israel was identical to the Nazis’ claim on ‘the loyalty of persons of German birth or descent’ wherever they lived.” Time magazine, inexplicably, called Ben-Gurion’s actions a form of “inverse racism.”

Israel proceeded, undeterred, animated by a sense of justice. David Ben-Gurion also had an educational agenda. Israel’s young people had been raised in a society that had thus far avoided confronting the Holocaust. It was time for a public reckoning, the prime minister believed. “Israeli youth should learn the truth of what had happened to the Jews of Europe between 1933 and 1945.”

So in a bold move in which Israel claimed jurisdiction for a crime that had taken place on a different continent, before the state had been established, by a murderer nabbed from yet a third country, Israel placed Adolf Eichmann—symbol of the Nazi regime—on trial. This time the guards were Jews, not Nazis. Now it was not Jews who stood trapped behind barbed wire, but the accused Nazi who sat behind a protective glass cage in a court of Jewish judges, in Jerusalem, the capital of the Jewish state.

EICHMANN’S TRIAL WOULD BE the first time that Israeli society would publicly engage with the horrific details of the atrocity and with the nightmares that many Israelis—survivors of the inferno of Europe—carried with them every day.

In the United States, among leaders of the Jewish community, the response to Eichmann’s capture was outrage. Joseph Proskauer, a former president of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), urged Prime Minister Ben-Gurion not to try Eichmann in Jerusalem but to turn him over to an international tribunal. Proskauer, who had been at the helm of the AJC’s anti-Zionist wing and had explicitly objected to the creation of a Jewish state, had said years earlier that he viewed Zionist efforts to establish a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine as nothing less than a “Jewish catastrophe.” He might have softened in the interim, but Proskauer was still appalled by Israel’s move. To try Eichmann in Jerusalem would be to acknowledge that Israel spoke for and acted in the name of world Jewry, and the AJC had long been on record as taking the position that the small Jewish state was anything but the center of the Jewish world.

Nor did Proskauer, a member of a generation of American Jews deeply conscious of how they were seen by “ordinary” Americans, seem comfortable having the spotlight on Jews alone. Eichmann, he reminded Ben-Gurion, had committed “unspeakable crimes against humanity, not only against Jews.” Proskauer actually clipped a Washington Post editorial that insisted, “Although there are a great many Jews in Israel, the Israeli government has no authority . . . to act in the name of some imaginary Jewish ethnic entity,” and sent it to Ben Gurion.

Erich Fromm, the German-born Jewish psychoanalyst and philosopher, was also enraged. He wrote (somewhat inexplicably) that by grabbing Eichmann, Israel had committed an “act of lawlessness of exactly the type of which the Nazis themselves . . . have been guilty.” Erich Fromm, of course, was hardly a fool, and equating Israel’s capture of Eichmann with the actions of the Nazis was an extraordinary accusation.

What could have provoked his response? In contrast to Fromm, Rabbi Elmer Berger, a leader of the vehemently anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, which had long opposed a Jewish state because it believed that “Jewish nationalism tends to confuse our fellowmen about our place and function in society and diverts our own attention from our historic role to live as a religious community wherever we may dwell,” was clear about the reason for his objections to Eichmann being tried by Israel. The Jewish state’s trying of Eichmann would essentially define Israel as the center of Jewish gravity, which would in turn disenfranchise American Jews. Berger would eventually call the Eichmann trial “a Zionist declaration of war” against American Jews’ claim to equal citizenship.

David Ben-Gurion was appalled and outraged by the reaction of these American Jewish leaders to what he saw as the enormous accomplishment of Israel’s security apparatus. He believed with every fiber of his being that the creation of Israel was the fulfillment of a biblical promise and two thousand years of Jewish aspiration. For him, as for most of his colleagues in the leadership of the Zionist movement and the Jewish state, the course of European history had proven without a shred of doubt that Jews dared not live without a country of their own. And to him, it was patently obvious that Israel had every right to try Eichmann. After all, the very point of the Jewish state was that people could not kill Jews with impunity, as they had done as long as the Jews had not had a state. Not only would the Eichmann trial hold Eichmann responsible as an individual, but it would make clear the long reach of Israel’s arm. No murderous enemy of the Jewish people would ever be safe again, anywhere. Ben-Gurion minced no words, arguing that “Israel is the only inheritor of these Jews [murdered in the Holocaust] for two reasons; first, it is the only Jewish state. Second, if these Jews were alive, they would be here because most, if not all of them, wanted to come to live in a Jewish State.”

The enmity between the two communities was almost as old as the Zionist movement itself. Even today, it is impossible to meaningfully understand the tensions between the two communities without first appreciating how differently European Zionists and American Jews understood what it was that Zionism was seeking to accomplish.

What was Zionism seeking to accomplish? What was the purpose of the state that it created?

That’s a question that we do not ask ourselves often enough, and it’s the subject of next Monday’s column.

Rabbi Mike Feuer is the host of a podcast on Jewish history called The Jewish Story: A Wandering Jewish History Podcast. He asked me to have a conversation about what I’ve previous called Menachem Begin’s “biblical statesmanship,” a subject I haven’t revisited in a long time, so I agreed with pleasure.

Mike is a great interviewer and the conversation was fun. He just posted it, so I’m sharing the link with you here, below.

The Iran Threat: Is there anything Israel can do? Is there anything Israel should do? Is a renewed Iran agreement a good or bad idea for Israel?

June 7 will be the anniversary of Israel's attack on the Osirak nuclear reactor in Iraq, which inaugurated the "Begin doctrine," a position that said Israel will never allow one of its enemies to acquire a weapon of mass destruction.

With Iran and the possible renewal of the JCPOA back in the news, we turned to Chuck Freilich, a noted author, scholar and former deputy national security adviser in Israel, to ask him about the threat. Is the threat real? Is there anything Israel can do? Is there anything Israel should do?

What he thinks Israel should do will surprise you.

Here is a brief excerpt from the conclusion of our conversation, not the part about Iraq, but the section in which Freilich reflects on what Israel really is. The full conversation about Iraq and more, for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside, will be posted on June 8.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

The text here is taken from two of my books, Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn and We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel.

It wasn't Resolution 132 but rather 138. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/112107