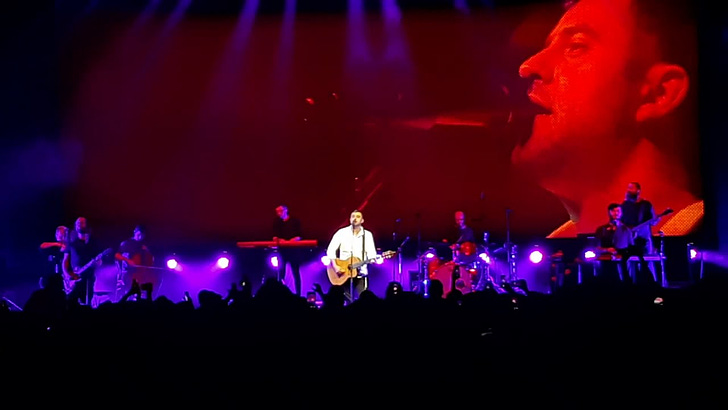

The clip above, part of the longer video below, is a performance of Seder Ha-Avodah, the “Avodah Service,” by Yishai Ribo in Jerusalem a few years ago. In today’s column, we’ll explain a bit about the song, but perhaps more importantly, suggest that this phenomenon of classic liturgy meeting “secular” Israelis is actually much more than a cultural curiosity. Why?

In this hurting and increasingly exhausted country, attachment to tradition may prove to be the source of resilience that our survival demands. More on that below.

The classic Avodah service (you can read through it on Sefaria), which is part of the Yom Kippur day-time liturgy, recounts ancient ritual in which the High Priest would enter the Holy of Holies to plead for forgiveness for the Jewish people. Jews have recited it for hundreds of years, some of the melodies also going way, way back.

But if you were to wander around the streets of Israel two days from now, on Yom Kippur, you would hear many synagogues singing parts of that service in a melody that is merely five years old. It’s a melody written by Ishay Ribo and released as part of his 2019 album, “Elul 5779.”

Ribo is a massive phenomenon in Israel (and in the US, too—he was the first Israeli artist to headline Madison Square Garden). He was born to a traditional Sephardi Jewish family in Marseille, France, before emigrating to Israel at age 8. Once in Israel, Ribo attended the national-religious school system, and later studied in a Haredi yeshiva in Jerusalem. For part of his IDF service, Ribo sang in the rabbinical choir. He was also the first religious singer to join the enormously popular Idan Raichel Project, which we’ll write about down the road.

Ribo has produced a number of albums, and though the entire Elul 5779 album was well received, one song, in particular—this song about the High Priest—rocketed to national prominence, among religious and secular Jews alike.

First, the song, and then, why it matters.

Ribo’s Song, Seder Ha-Avodah

Much of the song simply takes the words of the classic liturgy and puts them to a new melody. But there are also dramatically new words, which in very traditional circles, might be considered heretical. But Ribo is unabashedly firmly in the religious community, so no one questions the reverence with which he wrote the new version (layout below from Makom):

Here is the song in its entirety, to which we’ve added English subtitles (with an alternate translation):

To get a sense of the different energy the song has when he performs it live, take a quick look at at this clip (start at about 3:30 if you don’t want to watch the whole thing):

So, what did Ribo change? (Below, more on why it matters….)

The genius of Ribo’s song is that he didn’t just take the words of the liturgy and put them to a new melody, compelling though the melody is. While the classic liturgy recounts how every step, every move, every location of the High Priest on Yom Kippur was precisely prescribed, that’s not the world of Ribo’s song.

In his words, the song says:

He came from the place he came and went to the place he went, stripped off his weekday clothes and donned his white garments.

This is a different High Priest. The High Priest is now us, who can come from any place, and go to any place. We’re all priests, he’s essentially saying. There are many more changes, some of which you can read about in this excellent commentary on the song on Makom’s excellent website.

Much about the High Priest’s Yom Kippur day is transformed in Ribo’s song. In the classic liturgy, it’s the sprinkling of the blood that the priest counts in a unique way:

Each time he sprinkled, he counted aloud: One; One and one; One and two; One and three; One and four; One and five; One and six; One and seven.

But in Ribo’s song, something has changed:

And if one could recall the deficiencies, the flaws, the transgression and sins and all, Surely he would count thus: One, one and one, one and two, one and three, one and four, one and five.

Now, the High Priest is counting not the sprinklings of blood, but his sins, our sins. Somehow, it’s not the priest who will achieve atonement for us, but we, ourselves.

And then he takes the counting again, and transforms it into a message of deep hope:

And if one could recall, all the loving kindness, the goodness, all the compassion and salvation surely he would count thus: "One, one and one, one and two, one of a thousand, thousands of thousands and myriad myriads of wondrous miracles."

Why does any of this matter?

“So what?”, one might ask. A very talented guy takes the liturgy, popularizes it with slightly different words, a different melody and a good band. Nice, but who cares?

I think it matters a great deal. Because Ribo is not alone.

What he are others are doing is blurring boundaries between the world of the religious and the “secular” (which is not really secular), to beckon to everyone. This isn’t the province of the religious, he’s essentially saying. This is all of us. By making the Yom Kippur prayer into something that is played on regular radio stations, Ribo dismantles the supposed boundaries between classical and modern, religious and secular, liturgy and prose.

And why does that matter, now more than ever before?

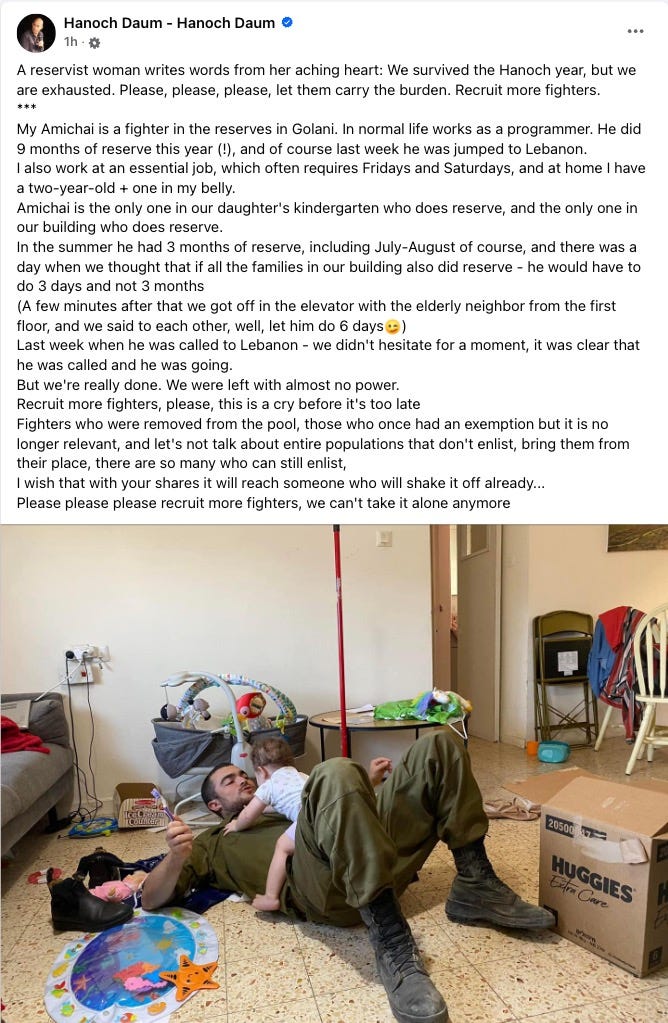

Because this year, Yom Kippur will be very different even from Rosh Hashanah last week. Since Rosh Hashanah just a week ago, thousands of soldiers have been called up. People who were in our community last week are in Lebanon this week.

And this has been going on for a long, long year. All across the Israeli press and Israeli social media, one can see the signs of a nation increasingly exhausted, cracks beginning to appear. They’re not huge yet, and perhaps they won’t become huge. But they could.

Here’s a Google translation of a page from Haaretz yesterday:

And here’s a post from Hanoch Daum (one of the co-hosts of the Families’ Memorial Ceremony we wrote about the other day). This is also a Google translation, and a bit clumsy, but it’s close enough to convey the idea:

This isn’t the sort of thing that the “red meat eating” Zionists of the Diaspora want to talk about. It’s easier, and of course more inspiring, to recount (the very real) stories of bravery and victory. Israel as the little engine that could, and did, and will.

Those are an important part of the story, but they’re not the only part of the story. Another dimension of the story is that this is longer, harder and more agonizing than any of us imagined it would be a year ago. The hostage story is a catastrophe, tragically with no end in sight. Those us of who have kids in Gaza or Lebanon don’t sleep, can’t focus. Many of the “kids” who are “in” have wives, and kids of their own. Those wives also don’t sleep, can’t work, have to take care of kids all by themselves (being a grandparent in Israel has thus become a very different role than it was a year ago).

What does all that have to do with Ishai Ribo?

For us to persevere, to hang on as long as it takes, this is a country that is going to need to plumb the depths of faith, a faith that many people here did not examine before. It doesn’t have to be religious faith, necessarily, but it has to be faith in something. History? Destiny? Home? Peoplehood?

Pride in Israel as a start-up nation with a booming economy in which Tel Aviv was essentially a Hebrew-speaking European city was great, when the cost wasn’t this high. But now the cost is sky-high, and it could go higher. Why, then, people will inevitably ask, does it matter? Why stay? Why raise children here? What is this place all about?

That’s the conversation that one can hear more and more Israelis having, not as a way of saying that Israel doesn’t matter, but rather, as searching for meaning, for rootedness, for a sense that we’re the continuation of something sacred, regardless of how we define “sacred.”

That’s why the Avodah service on Israeli radio matters. That’s why mixed Yom Kippur worship in Tel Aviv, religious and secular, matters. It’s why all the other musicians blurring these lines and making Jewish tradition part of the life of “secular” Israelis matters.

That’s why, if you were to roam the streets here two days from now and hear that melody, you might well start humming along. You might also find yourself brimming with faith and with hope you didn’t know you had.

G’mar chatimah tovah.

The Israeli rock star who will be heard in many synagogues this Yom Kippur—and why it matters