In the middle of the night last night, at around 2:00 a.m., I turned on the TV. The news had announced earlier in the day that over the course of the night hours, Channel 12 would be reading out the names of all the soldiers and civilians who have been killed since October 7, 2023.

It would take, they said, the entire night.

I clipped a very small portion (see video above) to give a sense of what Channel 12 did, all throughout the long, long night.

As you watch, even without English subtitles, you can see the age of the person along with her or his photo. The words tell where they were when the were killed, and if they were in the army, what unit.

At other points, you will hear במסיבה בראים, be-mesiba be-re’im. “At the [Nova] party at Re’im.”

For most of the soldiers, you hear the phrase, נפל בעת מילוי תפקידו, nafal be-et milu’i tafkido. “S/he fell in the course of carrying out his/her assigned duty.”

There’s very little in Israeli culture that doesn’t have an antecedent. And part of what we seek to do in IFTI is to illuminate those references, to share the full power of what’s being said, or sung.

If you know Israeli cemeteries, then the phrase we mentioned above, נפל בעת מילוי תפקידו, nafal be-et milu’i tafkido, “s/he fell in the performance of her/his duty,” can send shivers up your spine. The phrase is ubiquitous here.

One of the places where those words are most chilling is in the section of the Mount Herzl Military Cemetery that commemorates the fighters in the Jewish underground who fought for independence before 1948.

“The underground,” hence the design of this particular memorial.

Next time you’re there, read the plaques on the wall. Each of the plaques has the name, the age and the date of death. If you look carefully, you’ll see plaques that say, NAME, Aged 9 at his death, “he fell in the performance of his duty.” And 11 years old. And 10. And so on.

9 years old and he was killed in the performance of his duty? What does that even mean?

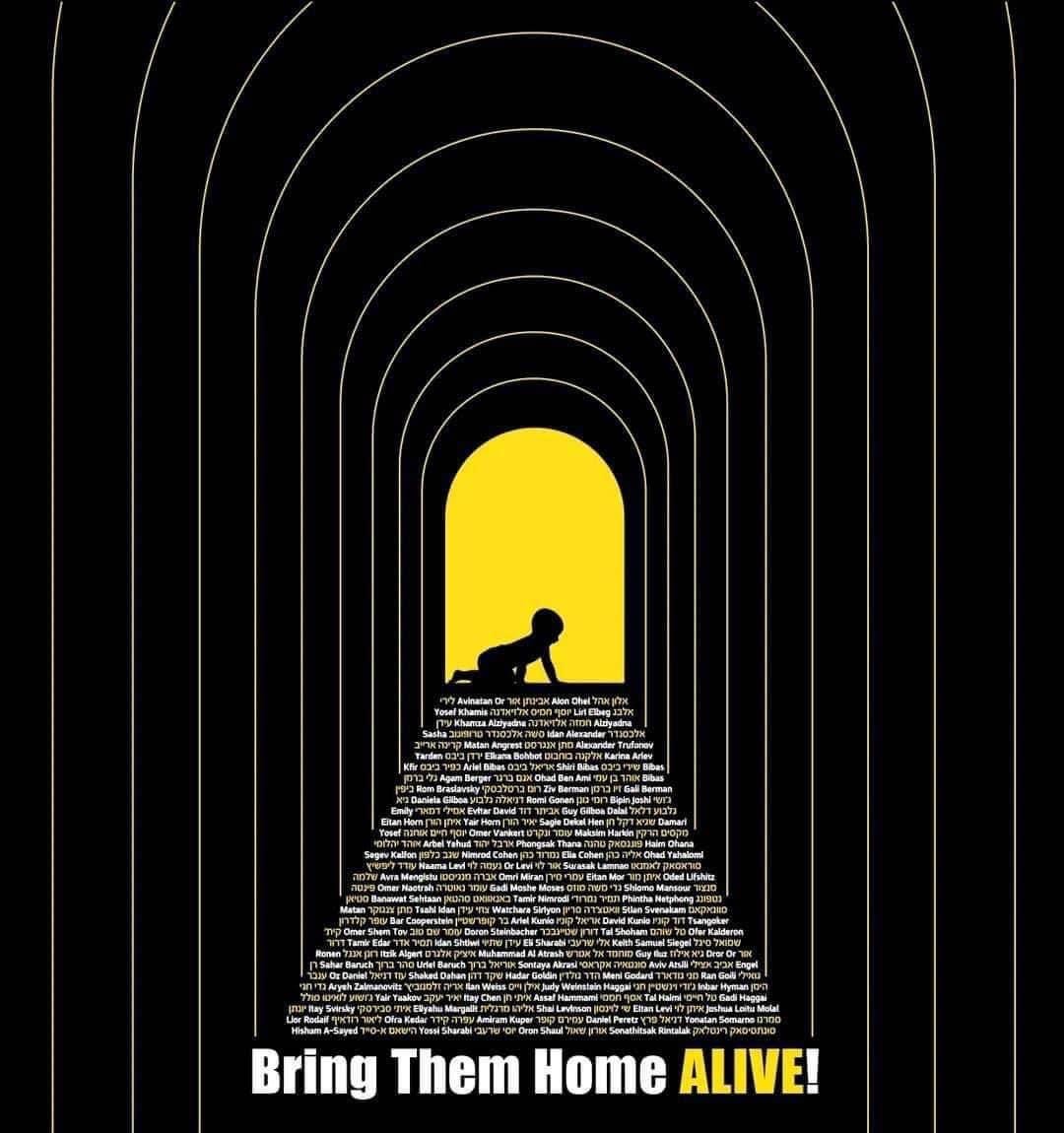

On a day like today, with this choking, agonizing anniversary coloring everything, and with rockets still flying out of Gaza today, missiles from Lebanon still striking Israelis in the north, rockets sirens at the airport, more soldiers killed, hope dimming for 101 hostages and Iran still unaddressed, it can be hard to put one foot in front of the other.

But then you remember that there were nine-year-olds, 80 years ago, who “fell in the performance of their duty.”

And you realize—losing hoping is not a privilege we have. Those of us who were borh here and live here, or who moved here to make this nation the central cause of our lives, have been left no choice but to soldier on, to weather the horrific losses that are still bound to come, and to somehow—this year, next year, or some day after that—emerge victorious.

We owe that to all who came before us, who already gave everything. We owe it to the history of our people.

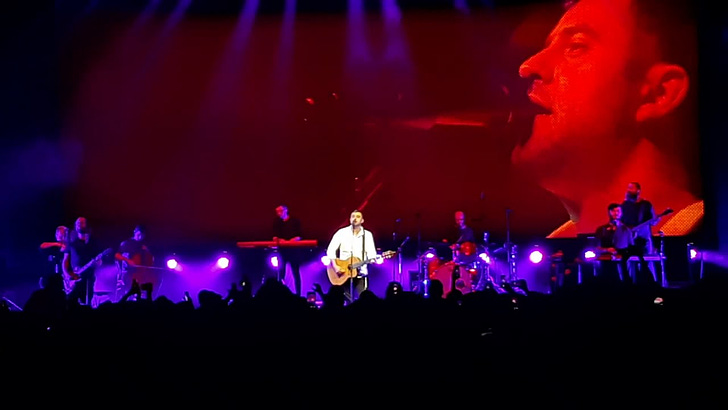

At the National Library of Israel, last night, there was a memorial ceremony, largely of music. The evening was called “Be-Tom Tishrei [At the End of Tishrei: An Evening of Song and Remembrance.”

That seems like a strange name for the evening, no? Why “At the End of Tishrei” if the month of Tishrei is just beginning? Because those words come from a famous Naomi Shemer song, “The Harvest”, with which the evening opened:

Naomi Shemer, arguably Israel’s most prolific singer and songwriter, is also credited with Yerushalayim shel Zahav (Jerusalem of Gold) and Al Kol Ele (Over all of These) — see our post on that song here and the video included there, recorded in much more joyous times.

Shemer’s song is about more than about the end of Tishrei, which would be Sukkot more than the week between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Assif, after all, means “harvest,” which is commonly associated with the holiday of Sukkot, since the holiday is otherwise known as the festival of the harvest (chag ha’assif).

The song lyrics also contain references to the Yom Kippur prayers; for example, the line “nedarai ve’asurai” translates to “my vows and prohibitions,” and is taken directly from the first line of Kol Nidre, the prayer that begins Yom Kippur. The (AI generated) translation of the portion of the song in in the video above reads:

And no more does a stem dream of its ear of grain, And no more are there "vows and prohibitions." Only the wind's promise that the rain in its time Will still grace its dust at the end of Tishrei.

Why call the evening “Be-Tom Tishrei”? Why open the evening with that song? In large measure, I suppose, because last year’s Tishrei never ended. Last year’s Simchat Torah, towards of the end of Tishrei, never ended. Because even when this year’s Tishrei ends on the calendar, last year’s Tishrei will still be hovering here, heavily.

Why call the evening “Be-Tom Tishrei”? Because Shemer’s song, this year, is a prayer. That one day the rain will come, that it will grace its dust, bringing the longest Tishrei in our history to the end we desperately need.

The play between ancient and modern, between liturgy and song, between religious and secular was evident everywhere one turned. Because one of the things that this horrible year has done has been to unleash the Jewish spirit deep at the core of this country.

The video below (taken by my son) is of the ceremony at Kibbutz Nir Oz, one of the kibbutzim that was horribly attacked and largely destroyed on October 7. At Nir Oz alone, 74 people were kidnapped. Others were murdered. Parts of the kibbutz were destroyed.

And still, at Nir Oz, this morning, people gathered, to remember and to sing. And on this very, very secular kibbutz, they sang, in part, songs from and based on the high holidays liturgy. (Note that Tishrei appears here, too…)

The story of the two melodies combined in this performance speaks volumes.1 The melody for the classic words of the liturgy was written in Beit HaShita, a kibbutz that had lost the eleven young men in the 1973Yom Kippur War.

The kibbutz’s agony festered for years, and finally broke wide open in 1990, seventeen years after the war, when Yair Rosenblum, one of Israel’s most prolific songwriters, visited the kibbutz. He ended up writing a melody for the Yom Kippur liturgical poem “U-n’taneh Tokef,” which includes the words “who shall live, who shall die, who by fire, who by water,” words that every religious Jew knew well, language that even many secular Jews remembered from their parents or grandparents.

Rosenblum recruited Hanoch Albalak, a member of the kibbutz known for his beautiful voice, to sing this new melody to a classical, deeply religious text at the Yom Kippur ceremony of this passionately secular kibbutz.

Matti Friedman described what happened next:

The song was sung at the end of the ceremony on the eve of Yom Kippur that year, 1990. Rosenblum had introduced an unapologetically religious text into a stronghold of secularism and touched the rawest nerve of the community, that of the Yom Kippur war. The result appears to have been overpowering. “When Hanoch began to sing and broke open the gates of heaven, the audience was struck dumb,” Shalev wrote. “Something special happened,” another member, Ruti Peled, wrote in the same kibbutz publication from 1998. “It was like a shared religious experience that linked the experience of loss (which was especially present since the war), the words of the Jewish prayer (expressing man’s nothingness compared to God’s greatness, death to sanctify God’s name and accepting judgment) and the melody (which included elements of prayer).” “When I sang, I saw more than a few people crying,” Albalak recalled.

As Matti Friedman relates in his fabulous book, Who By Fire: War, Atonement, and the Resurrection of Leonard Cohen, Cohen had also visited Israel during the Yom Kippur War, and his “Who by fire, Who by water” emerged from that experience.

This morning, at kibbutz Nir Oz, a performance of the famous Yom Kippur prayer-poem Unetaneh Tokef was sung, the words of the classical prayer interspersed with translated and freely adapted lyrics of Leonard Cohen’s song, “Who by Fire.”

The translation of what was sung is below, with Leonard Cohen’s (changed) lyrics italicized and the words of the traditional prayerbook in regular print:

Let us voice the power of this day's sanctity-- it it awesome, terrible On this day, Your kingship is raised Your throne is founded upon love and You, with truth, sit upon it [melody shifts to Leonard Cohen's, his words significantly adapted] Who by the blade, who by water Who by great fire, who by darkness Who by the hand of a judge and who by the hand of an executioner Who will begin, who will end in Tishrei, who in my royal Shevat And who, who is it that calls out "Where are You? Who in hallucination, who alone in her room Who in the embrace of her beloved, who by a sharp object Who under a heavy burden, who by a kiss Who by gunpowder, who by a transparent tear And who, who is it that calls out "Where are You?" [melody shifts to Rosenblum's, words from the traditional liturgy] In truth, it is You Judge and Accuser, Knowing One and Witness writing and sealing, counting and numbering, remembering all forgotten things You open the book of memories-- it is read of itself / and every person's name is signed there [melody shifts to Leonard Cohen's, his words adapted] And who for the sanctification of [God's] Name, who that is not guilty Who because of hatred, who facing the mirror Who by the hand of his brother, who by his own hand Who as a lamb for the sacrifice, who in the murmur of a prayer And who, who is it that calls out "Where are You?" [melody shifts to Rosenblum's, words from the traditional liturgy] It is read of itself / and every person's name is signed there A great Shofar sounds, and a still small voice is heard angels rush forward / and are held by trembling, shaking [melody continues with Rosenblum's, but with the liturgy's words significantly revised] Who will rest, who will wander Who in their hunger and who in their thirst Who in their sufferings, who in their final end Who in an instant, who as prey And who, who is it that calls out "Where are You?" And who, who is it that calls out "Where are You?"

“Where are you?” panicked young people at the Nova festival called out to the army. But the army did not come.

“Where are you,” screaming adults and children in safe rooms that were not at all safe called out to the police as their lives ebbed away. But the police did not come.

“Where are you?” a grieving nation called out to its leaders in the weeks that followed, but the government did not come.

“Where are you?” the nation is still asking the statement of accountability that no one has heard.

“Where are you?” people wonder, when they think the Commission of Investigation that has not been appointed.

There are many “Where are you’s” that were never answered, that have still not been answered. And for those who died as a result of that, this is a country bowing its head today.

Yet as it bows its head, this country also knows that many people did answer the call. They raced into battle. Too many of them are the ones who were listed, along with hundreds of others, in that video at the top. Others manned the operating rooms. They took to the cockpits. They created civilian command centers. They picked fruit. They’re still cleaning defiled homes so that people can return. They’re coming out of battle, waiting to go back in, saying that when they get out, declaring that when this is over, they’re going to take the reins.

There were, and are, a lot of “Where are you’s?”

But there have also been incessant “Here I am’s,” as well.

And one day, in a future that none of us can yet imagine, those “Here I Am’s” are the ones who are going to heal this nation.

They are the ones who are going to rebuild the one place on this planet Jews can truly call home.

Gordis, Daniel. Impossible Takes Longer: 75 Years After Its Creation, Has Israel Fulfilled Its Founders' Dreams? (pp. 213-214). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

"The dust at the end of Tishrei" — On a horrific anniversary, a heartbroken nation sings and (partially) holds back tears