There but for the grace of home ...

The humanitarian horror unfolding in Afghanistan, and what it says about Zionism and Israel

Those of us of a certain age remember Srulik, the lovable character (above) created by Kariel Gardosh (known as “Dosh,” see his signature at the bottom of the cartoon). Srulik is a diminutive of Yisrael (Israel), and thanks to Dosh’s talents, he became synonymous with the friendly, sweet, sometimes naive Israeli.

Srulik had that then-ubiquitous Israeli dress: Sandals. Really short shorts. A hat known as a “kova tembel,” now available mostly in tourist shops. Kariel Gardosh died in 2000, but the love many Israelis feel for the iconic character that he created lives on.

One needs to remember Srulik to appreciate a cartoon that appeared in Makor Rishon, an Israeli newspaper, over the weekend.

The Makor Rishon cartoon was a play on Srulik, and a response to the horrors unfolding this week in Afghanistan. A Srulik-like character peers up at an American military plane, with human beings falling out of it, plummeting towards their deaths. Srulik in this cartoon has lost his characteristic smile. He looks more confused, worried, contemplative.

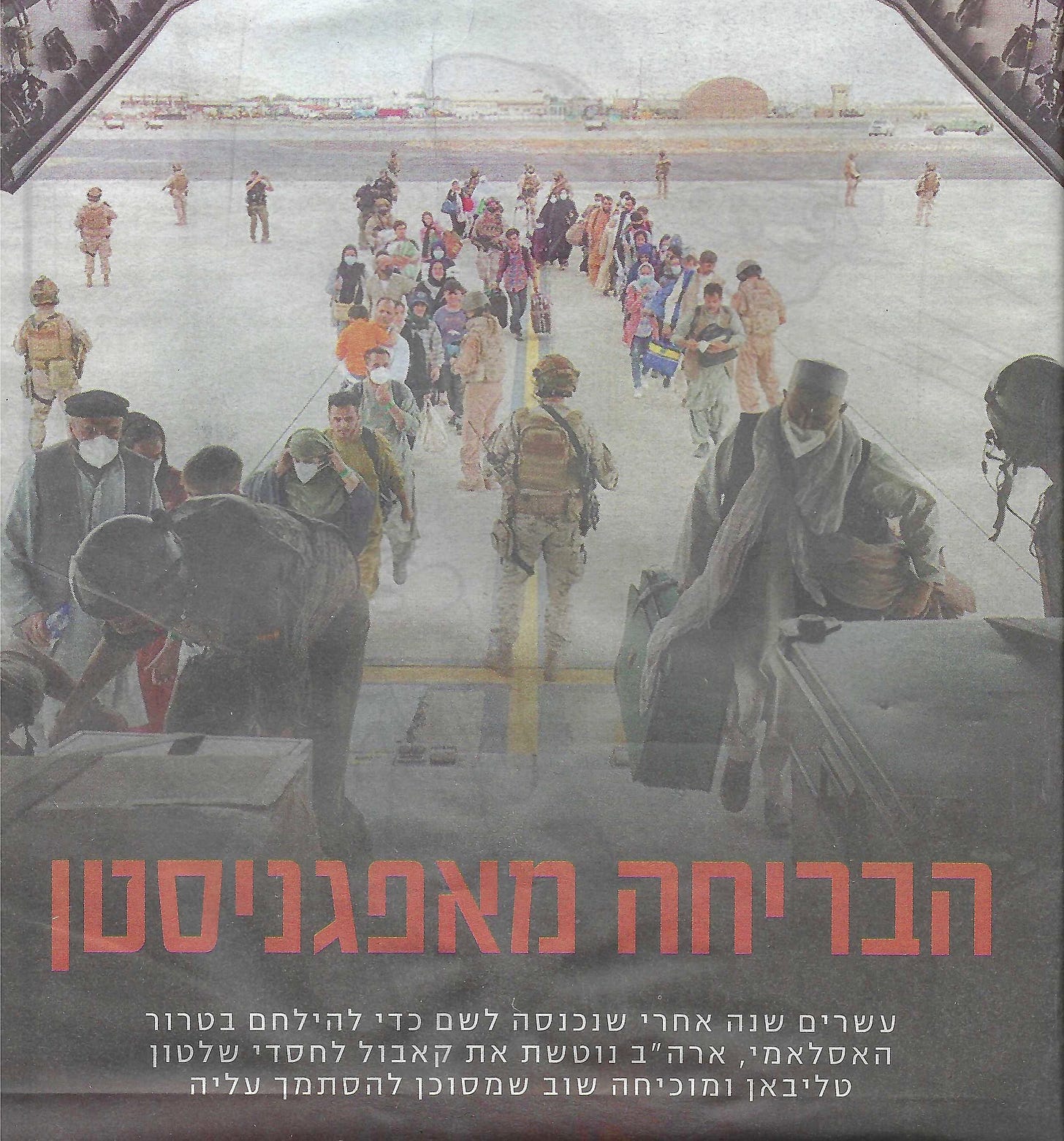

Why? The cover of the same magazine explained the point explicitly:

The red writing says “The Flight from Afghanistan.”

“The flight from ….” is a ubiquitous phrase in Israeli parlance, almost always associated with “The flight from Lebanon,” an ongoing critique of how Israel fled Lebanon in 2000. Israel left (“fled”) Lebanon after eighteen years with not much to show for the death and the cost, abandoned the Lebanese SLA fighters who had fought alongside the IDF, left weaponry behind, and more. In other words, the cover is saying, to quote another Israeli phrase, “we’ve seen this movie already.”

Let’s go back to the big black letters under the “Srulik” staring up at the American plane. Those letters say taliban zeh kan, or, “Taliban — that’s here.” That, too, is an insider’s Israeli idiom, based on yesha zeh kan, or “Judea and Samaria — that’s here.” It was a phrase made ubiquitous by those who were opposed to Oslo. Get out of the West Bank, they were saying, and the land you’re being pressured to give up there will be the land you’re pressured to give up “here,” wherever “here” was—Tel Aviv, the Galilee, the Negev.

The point of the gigantic caption under the cartoon? Don’t think that the “Taliban problem” is far away, “over there. It’s right here.”

Which brings us to the white print on the cover with the photograph. The latter part of the writing says,

“The United States abandons Kabul to the graces of Taliban rule, proving once again that it’s dangerous to depend on the U.S.”

Thus, here is the first Israeli takeaway from what just happened in Afghanistan—and you hear it everywhere in these parts. More or less, it goes like this:

Everyone should remember that America has always been “America First,” and always will be. Of course there’s a strong alliance right now—and it will remain good as long as it’s good for America. And when it’s not, like the desperate Afghans who climbed into wheel wells to escape the horror of life under the Taliban only to plummet to their demise, we will be entirely on our own.

That, by the way, is no partisan issue. Israelis remember well that Donald Trump was going to pull US troops out of Syria, which would have left almost nothing between ISIS and the Israeli border, and would have created a superhighway for arms from Iran to Lebanon. It’s not Trump, it’s not Biden—it’s America, Israelis are saying.

A second point, that I haven’t seen anywhere but that I think merits recollection on a week like this is that ironically, while “America First”—which closely correlates to American xenophobia—might worry Israelis now, American xenophobia also made Israel possible.

Without American xenophobia, there might well be no Jewish state.

Why? Because in ways that we often don’t think about, it was the Johnson-Reed Act, more commonly known as the Immigration Act of 1924, which unintentionally created in Palestine the critical mass of Jews necessary for creating a state. In fact, until Congress passed that act in 1924, of the millions of Eastern European Jews fleeing the horrors of Poland and Russia, the overwhelming majority went to the United States. Only a very small group went to Palestine.

The Johnson-Reed Act reversed that, permanently.

In 1914, for example, 138,051 Jews immigrated to America from Eastern Europe. The number that went to Palestine was about 4,000.1 In other words, the number of Jews who chose America was more than 30 times greater than the number who chose Palestine.

Take 1921. In that year, 119,036 Jews immigrated to America from Eastern Europe. About 9,000 went to Palestine. The group that chose America was some 13 times larger than the group that chose Palestine.

Then came in the Immigration Act of 1924. In 1924, some 49,989 Jews chose America, while 12,856 went to Palestine. The gap had closed, and dramatically. And in 1925, for the first time, the seesaw tipped. There were 10,292 Eastern European Jewish immigrants to the United States, while 33,801 went to Palestine.

The seesaw would never tip back. Jewish immigration to America would never return to what it had been, and America would keep its shores closed even during the Holocaust, so the flow of people fleeing Europe turned sharply in the direction of Palestine. It was thanks to America’s xenophobia that by the time 1947 rolled around, the UN was convinced that there were sufficient Jews in Palestine to give a Jewish state a try.

And finally, my third takeaway: The image of these Afghans, abandoned by the world, with nowhere to go, no way to get out, ought to remind us of … ourselves.

The fact that it doesn’t, by the way, is testament to how utterly successful Israel has been in transforming the existential condition of the Jew. We see the Afghans, we don’t think of Jews, anymore. But we should. Because without Israel, that’s who we might be.

Sound extreme? Consider three ships, and we can begin to remember.2

One was the St. Louis. In May 1939, the St. Louis sailed from Hamburg to Cuba with 937 passengers. After Kristallnacht, the mostly German Jewish passengers understood that they needed to flee, so they had bought legal Cuban visas. When the vessel arrived at its destination, however, Cuban president Federico Laredo Brú refused to allow them to enter the country. The non-Jewish German captain of the ship, Gustav Schroder, committed himself to finding a home for each one of his passengers. For many, though, Schroder found no home. More than a month after they had set sail from Europe, the passengers disembarked back on European soil in mid-June. As the war progressed, many of them—though they had been just ninety miles from the shores of the United States, which did not allow them in—found themselves once again under Nazi rule. By the end of the war, 254 of the passengers, just over a quarter of them, had been murdered by the Nazis.

The second ship: in November 1940, the SS Atlantic reached Haifa Bay from Romania, carrying 1,730 refugees from Germany. The British refused to let them enter Palestine and ordered them onto another ship, the Patria, which would take them to Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean. Members of the Jewish military resistance placed explosives on the Patria in order to delay its departure. But the plan backfired; as the first group of illegal immigrants was being escorted to the Patria the following morning, the explosives did significantly more damage than had been intended; the ship blew up and sank. More than 250 of the detainees drowned. The British sent the remaining immigrants who had arrived on the Atlantic to an internment camp in Atlit, not far from Haifa, where once again, just as was unfolding in Europe, the Jews found themselves behind barbed wire, surrounded by armed soldiers in guard towers. (You can still the Atlit camp; it's chilling.)

The third ship, the Struma, set sail from Romania on December 16, 1941, carrying 769 Jewish refugees to Palestine for what should have been a voyage of just a few days. Due to engine trouble, it anchored in the harbor of Istanbul. The Turkish government denied the passengers even temporary sanctuary, so the refugees lived on the boat for two months. The ship was equipped with only four sinks, one freshwater faucet, and eight toilet stalls that had no toilet paper. The Jewish Agency intervened and pleaded with the British to let the Jewish passengers enter Palestine, even temporarily, just to relocate them later to Mauritius. The British refused to take “surplus Jews.”

On February 24, 1942, the Turks ordered the Struma to leave the harbor. They towed the boat into the Black Sea, abandoning it there with no functioning engine. A Soviet submarine, operating under then secret orders to sink all neutral and enemy shipping in the Black Sea (to prevent raw materials from making their way to Nazi Germany), torpedoed the boat. The Struma sank almost immediately, drowning almost all the men, women, and children on board. There was but one survivor.

The St. Louis, the Patria, and the Struma brought home a single point with terrible clarity. Without a Jewish state, there would always be Jews who would have nowhere to go. They would be, as the British called them without embarrassment, just “surplus Jews.”

There are no surplus Jews in the world today. There are no Jews who have nowhere to go. It’s easy to take that for granted, but we shouldn’t. It’s because this place exists.

Israelis didn’t talk about that very much this week, but they know it. And because they know it, Srulik looks up at the plane with people tumbling out of it with a kind of worry. Whether each of us agrees or not (and reasonable minds can certainly differ), the editors of Makor Rishon said out loud what many people here were thinking:

“The United States abandons Kabul to the graces of Taliban rule, proving once again that it’s dangerous to depend on the U.S.”

The events unfolding in Afghanistan, which are a chilling reminder of why those Zionists leaders of the late nineteenth century were convinced that the Jews needed a state of their own, is an apt moment to consider some of the steps Israel has taken to preserve the Jewishness of the Jewish state.

One of the more controversial steps in recent years—particularly alarming to and unpopular with American Jews—was the Nation-State Law that Israel passed a few years ago. Israel from the Inside is about breaking out of our echo-chamber, exposing ourselves to people and ideas with whom we might not agree, but who can make us think.

With that goal in mind, we recently had a conversation with Dr. Moshe Koppel, a computer scientist, Jewish scholar, and political activist. Through a series of unexpected circumstances, Koppel, professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan University and the author of over 100 articles in leading academic journals and proceedings in mathematics, computer science, linguistics, law, economics, political science and other disciplines, found himself playing a critical role in the writing of the Nation-State law. In our conversation, he explained why he believes that the law is both just, and necessary.

Listen for yourself. Thanks to Koppel, I found myself thinking about the issue in ways that I hadn’t before. We’re making an excerpt of our conversation available today. Our full conversation will be posted later this week and will be available to subscribers to "Israel from the Inside."

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Numbers of immigrants to both countries are contested and there are varying accounts. But the orders of magnitude are clear even if the specific numbers differ.

The following account based on the discussion of these ships in my history of Israel, ISRAEL: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn.