We Wanna Dance with Somebody ... Who Loves Us

With apologies to Whitney Houston, here's why a new suggestion about how to revive American Reform Zionism is bound to fail

With the 26th week of protests now behind us, we’re officially half a year in. Judicial reform remains very much unresolved. The original plan mostly seems dead, but it’s hard to tell. In English, Bibi tells the Wall Street Journal that he’s not going to push through the portion about judicial review, and then, in Hebrew, he tells his coalition not to take those comments too seriously, that ending judicial review is precisely what he plans to do. What’s true, and what’s not, is anyone’s guess. How this will end is also impossible to know.

And with the legislative push back in gear, the protests are heating up again. The number of protesters throughout the country grew on Saturday night. On Monday, protest leaders vowed to block the entrance to Ben-Gurion International Airport, while airport authorities pointed to the emergency return of United Flight 91 to TLV after the pilots noticed cracks in the windshield. Blocking the airport could prevent emergency vehicles from getting to the airport if needed, authorities said, pleading with protesters to leave the airport out of their plans. Then the pilots’ association chimed in, saying that that claim was bogus, that there were plenty of emergency access routes to the airport if needed, and the protests posed no safety challenges. Again, what was true and what was not remained entirely unclear.

But several things are clear. Half a year into the protests, no one has been killed. No one has been seriously injured. With the exception of the (totally unacceptable) break-in to the offices of the Kohelet Forum (which helped draft the judicial reform), there has been no looting, virtually no violence. There have been only a handful of cases of police overreaction. And this week, a soldier who threw a rock at protesters from inside the IDF military headquarters in Tel Aviv was promptly tossed into jail for thirty days.

The country is tense, but not (at least on the surface) as obviously explosive. It is sad, but no longer despondent. The protesters seem less panicked, but more determined. And still, in the midst of all of this, what almost everyone feels even in the heat of profound disagreement, is how their side—as well as the “other” side, no matter which side that may be—loves this country.

That love is why the protesters (on both sides) have adopted the flag as their symbol. That love is why, so far, there has been virtually no violence. That love is what one senses from the most clever signs each week—the talent of some of Israel’s best graphic designers has been much on display in recent weeks.

People have turned out to the streets because they love their country, not in the hopes that protesting might get them to love the country.

There’s a huge difference between the two. We’ll return to love—and its absence—below.

About four years ago, I published a book with the title We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel. It turned out to be much more controversial a thesis than I had imagined. The New York Times review1 seemed mostly bothered by the fact that I had written a book about Israel that did not focus on the occupation.2 I mentioned the occupation, of course, but not extensively, because the book was about something else—it claimed that the discomfort that many American Jews feel and felt about Israel had little to do with what Israel does, and much more to do with what Israel is.

Given that claim, I focused on the long-simmering resistance to Israel that had festered for decades, indeed for almost a century, among American Jews. American Jewish discomfort with Zionism preceded the occupation, it preceded the Chief Rabbinate’s disparaging (and repulsive) comments about non-Orthodox Judaism, and it even preceded the Likud party. That was why I chose to focus on issues way in the past, and much less on matters of the present, like the occupation. I believed then, and still believe now, that it’s permissible to write a book about Israel in which the occupation is not the central subject. But the Times wasn’t happy.

Neither, for that matter, was Rabbi Eric Yoffie, one of America’s leading Reform Rabbis, very happy with the book. (It would be difficult to imagine someone more passionately devoted to the Jewish people than Rabbi Yoffie. In addition to his distinguished congregational career, Rabbi Yoffie served for years as the President of the Union for Reform Judaism, and, among many other accolades, was named by the Forward as “America’s number one Jewish leader” in its 1999 Forward 50 list.)

When Rabbi Yoffie’s review of the book came out in Ha’aretz, the paper’s headline writers spared me the suspense of having to read the review carefully in order to know what Rabbi Yoffie felt:

Well, that was pretty clear.

Still, though, I read the review carefully. And Rabbi Yoffie, not at all surprisingly, described the book’s central claim quite accurately.

According to Gordis, American Jews have been unhappy with Zionism and Israel long before Israel was created, and before a Palestinian problem or a religious pluralism problem even existed.

Yes, that was what I’d said. And yes, I’m still convinced it’s true.

What did Rabbi Yoffie think about that claim?

Gordis argues that with the exception of the "honeymoon years" of 1967-1982, Jewish Americans have seen the whole idea of a Jewish nation-state as problematic and at odds with their universalistic vision of humanity.

But this is nonsense. Gordis correctly points to the serious reservations about Zionism that existed among American Jews in Israel’s pre-state and early state period. But the history of the last 70 years is one of steady growth of support, affection, and ultimately love of American Jews for the Israeli enterprise.

That last comment, the notion that the last seventy years have been characterized by American Jewish “love” for Israel (or for “the Israeli enterprise,” more precisely), seemed to me to be so patently false that there really wasn’t much to say.

But again, we’ll come back to “love.”

I’d totally forgotten about that review until I was reminded of it once again, by … Rabbi Yoffie. How? A couple of weeks ago, a new column by Rabbi Yoffie appeared in Ha’aretz, and once again, the headline stopped me in my tracks:

Rabbi Yoffie’s most recent column is, as he himself readily acknowledges, mostly an opportunity to disagree with Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch, another leading, deeply Zionist, Reform rabbi, who had given the keynote address at a “conference held at the beginning of [last] month at Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, a large Reform congregation in Manhattan.”

Rabbi Yoffie has many complimentary things to say about Rabbi Hirsch and his presentation, but then cuts to the chase of their disagreement:

And while [Rabbi Hirsch] condemns the extremists in Israel’s current government, his position is that the process of distancing from Israel was gathering strength long before this government came into existence. In fact, he asserts that the anti-peoplehood stance of late 19th to mid-20th-century Reform Judaism was not a historical aberration that ultimately gave way to Zionism, but that it was the historical norm.

Does that sound familiar? I actually chuckled when reading what Rabbi Yoffie said what Rabbi Hirsch had said. Did Rabbi Yoffie remember his review of my book? Did he notice that Rabbi Hirsch and I are making almost precisely the same point? I have no idea.

I read the actual text of Rabbi Hirsch’s keynote, and found there language that very closely mirrored my own claims in We Stand Divided:

It dawned on me only a decade or so ago, that the anti-peoplehood stance of late 19th to mid-20th-centuryReform Judaism — the rejection of Jewish particularism in favor of an almost messianic-like embrace of Western universalism – was not a historical aberration. The exception was not the Pittsburgh Platform, as I had assumed for most of my career. The exception was the 20th century that inflicted existential threat after existential threat on our people — Eastern European pogroms, Western European fascism, the Holocaust, Israel’s War of Independence, the Six Day War, the Yom Kippur War, Communism and the struggle to free Soviet Jews — these compelled even fervent anti-peoplehood Reform Jews to warm towards Jewish particularism for a period of time. But now, in an era of no perceived existential threats against the Jewish people; when, if anything, Israel is perceived by many liberal Jews as the neighborhood bully — and notwithstanding the distressing rise of Western anti-Semitism — it is natural, and we should have expected, that this strain of Jewish liberalism that denigrates Jewish particularism, would reemerge.3

Is there hostility to Israel deeply embedded in Reform circles? Rabbi Hirsch pulls no punches:

Given the growing hostility to Israel in our circles, liberal and progressive spaces, and mindful of the increasing disdain for Jewish particularism, it is not enough for us to proclaim our Zionist bona fides every now and again, often expressed defensively, and with so many qualifications, stipulations and modifications, that our enthusiasm for Zionism is buried under an avalanche of provisos.

How does Rabbi Yoffie respond?

The leadership of all the major Reform institutions has been staunchly Zionist, educational programs focusing on Israel have multiplied, extremely close ties to Israeli Reform Judaism have flourished and the North American Reform movement has affiliated with the World Zionist Organization. To be sure, some strident, anti-Israel voices can be heard from time to time, and they must be confronted whenever they appear. But in a large and diverse movement, these voices are generally confined to the outer fringes.

So we have two Reform rabbis, and two radically different assessments of the state of Zionism in contemporary Reform Judaism. Fair enough — disagreements of that sort have been, for thousands of years, the bedrock of Jewish conversation.

Why does any of this matter? It matters because, if we believe—as I do—that the relationship between American Jews and Israel is worth trying to preserve even without any guarantees that that will succeed (and I’m not optimistic), then we should be very interested in how leaders of different sorts propose breathing new life into American liberal Zionism.

After he lays out the differences between Rabbi Hirsch and himself, what does Rabbi Yoffie propose?

[i]f we wish to reignite Zionism in America – among Reform Jews and others – it will not be done in the usual way, with the usual slogans and the usual programs. We will reignite Zionism in America only by taking sides, by opposing this government, and by applauding and supporting in every way possible the protestors in the streets. …

If we want to strengthen Israel, restore Zionism’s good name and get the masses of American Reform Jews, and Jewish Americans of every type, to rally to our side, we need to take on and defeat the Smotriches and Ben-Gvirs who profess to represent Zionism, but are an affront to everything that the Zionist founders believed.

But here’s the rub…. People don’t fall in love with other people by trying to change them. If they seek to help that other person grow, it is because they already love them. It’s the same with countries. We become involved patriots, even if alarmed patriots, and work to make our countries better, only if we already love our country. If we don’t, then protests become nothing more than opportunities to pillage and steal—think Seattle and Portland. No one protested there out of love of anything at all.

My friends and I—on both sides of the divide—are as engaged as we are because we love this country, because of its vision for the Jewish people, because of what Jewish sovereignty has done for Jewish peoplehood. We’re on the streets (both sides) because we’re Zionists. I don’t know a single person going to the protests who hopes that protesting might lead them to love this country. No one I know enjoys the protests. Everyone I know is sick of them. No one I know is sure that their “side” is going to “win.”

But we’re out there not so that we might come to love Israel, but because we already do. We protest because our hearts are breaking and we want to save something, not because we think protesting anything will help them heal.

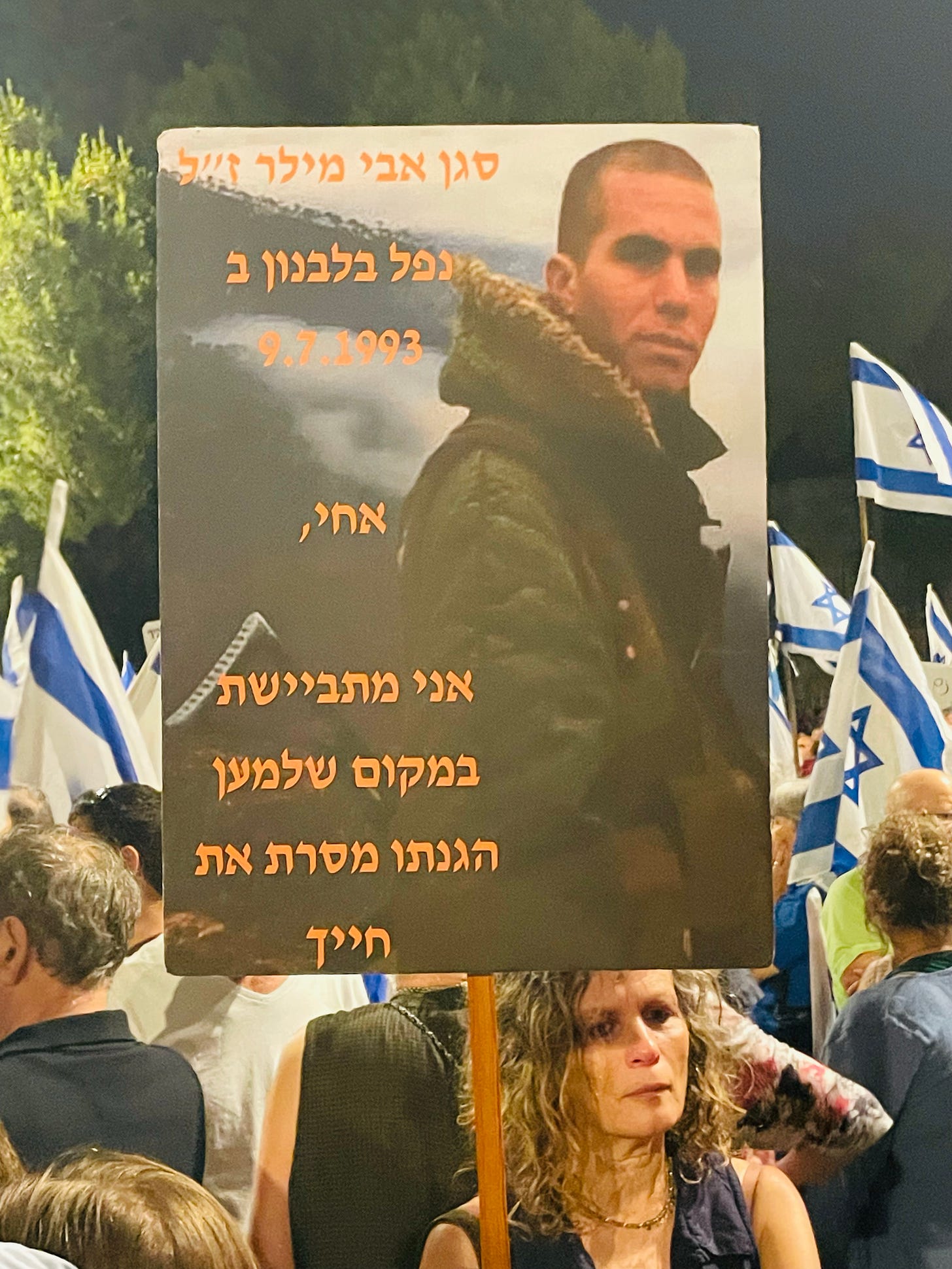

Not all the signs, by the way, are “clever.” Some are just heartbreaking. The one above reads: “Lieutenant Avi Miller, z’l. Fell in Lebanon on July 9 1993 [DG, ie., just about thirty years ago, to the day]. My brother, I’m ashamed of the place in the defense of which you gave your life.” Going to the protests can be crushingly sad, too.

The hope that “We will reignite Zionism in America only by taking sides, by opposing this government” cannot possibly work. If Zionism is about opposing this government, what if the protests fail? Those of us who love this place will stick it out and wait for our chance to fix whatever gets broken. But what about those whose Zionism is about opposing the government? If the government—or its values— persists, then their Zionism failed. Then what?

Zionism at its greatest was never just about opposing something. It was always about loving something. Loving a vision of the Jewish people restored to cultural grandeur, which Israel has provided. Loving a language brought back to life, which Israel has provided. Loving a new vision of the Jew, no longer (rightly) fearful of what history has in store, which Israel has provided. Loving a place where there are more people studying Torah than there were in Europe before the War, which Israel has provided. Loving a place which Jewish creativity and technology help improve the world everywhere, which Israel has provided.

Zionism was always about love. Always.

Zionism based on opposing a government is a Zionism bound to run out of gas when it’s still backing out of the driveway. If the government survives, then that “Zionism” failed. And if the government falls, that “Zionism” succeeded, and might as well close up shop. Let’s be realistic—people will be drawn to Israel not by opposing Ben-Gvir or Smotrich, but because they love the vision of the Jewish people restored to its ancient glory (or better) in its ancestral homeland.

Where’s the vision of something to love in Rabbi Yoffie’s suggestion for reviving Zionism? Which of those visions above, or many others that could be listed, would Rabbi Yoffie like Reform Jews of today to embrace? He gives us no indication.

Read Rabbi Yoffie’s argument again carefully. And look for the word “love” (or search for it). It’s not there. Not once. And that, I think, says everything.

I’m hardly the only one who’s concerned.

It’s true that many Israelis do not know nearly enough about American Jews, but those who are interested are deeply troubled by the superficiality of how American Jews think about Israel (Israeli Jews views of American Judaism are no less superficial, by the way). Take this news clip about the GA around the time of Israel’s 75th Independence Day that appeared on Israeli TV. Watch and listen closely, and look at the some (not all) of the clips they chose, and you can feel the exasperation with the “thinness” of the Zionism the reporters found:

These are worrisome times in Israel. They are frightening times. They are also inspiring times. They are times in which we are asked to demonstrate our love; but they are not times that will generate that love.

Israeli Zionists would love to be joined by Zionists around the world in their love of Jewish statehood. That was always the dream. But Zionism abroad cannot be based on opposition, or a narrow political agenda. It will fail to inspire, it will fail to launch. It will just plain fail.

We need Zionists who love the dreams that we love, who will weather the darker times because the vision is so grand. We do want to dance together. But, as Whitney Houston sort of put it, “we want to dance with somebody who loves us,”4 who loves not opposing parts of who we’ve become, but who loves the dreams that are still at the very core of who we are.

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

The Times review was rather error-riddled, as I pointed out in a response in the Times of Israel. But those errors are not germane to this discussion.

I’m aware that for many people, the word “occupation” is itself problematic. I’m also aware of the legal arguments used to claim that the occupation isn’t an occupation. I’m not rejected those arguments by using the term here. It’s the term that the Times and other reviewed used, so I’m using it here. The ways in which the term is and isn’t a useful or fair one are beyond the purview of this column.

The emphasis in the bold is not in the original. I added it for clarity.

Rabbi Gordis,

I started following your Substack a couple of years ago, as I wanted to learn more about “Israel from the inside.” I wanted to understand what it is like for Israelis right now, in this moment, and understand the culture and history more deeply. Your writing has been incredibly educational in this regard.

But these diatribes about the failure of American Jewry to support Israel are hurtful to me as an American Jew. Because yes, Israel needs our support, but we need Israel’s support.

Please help me understand how I can both support Israel and this sinking ship of American Jewry. Because I am failing. And I feel very alone.

The civilizational acid eating away at liberal Judaism—Reform and Conservative—is eating away at the U.S. as a whole. The headwinds we are facing are monumental. Israelis have no idea. Progressive thought and social justice theories like intersectionality and critical theory have taken hold in every institution, school, and corporation. We are bombarded every day with the message that to live a traditional life of any kind—Jewish, Christian, whatever—is to be backwards and bigoted. And that doesn’t even scratch the surface of the antisemitism that exists on both the right and the left in this country, rearing its ugly head after lying dormant for a couple of decades.

I finally visited Israel in February 2023, saving up for years to join a women’s trip with the Jewish National Fund. I was able to take one week off from my family to go, and it was eye-opening, and in many ways wonderful, and in many ways troubling. I met many real Israelis and saw Israel’s struggles, triumphs and challenges and beauty. But I was not inspired to live there. It seems difficult, expensive, violent and hot. I live in Colorado, a really nice part of the United States. My entire family is here. Making Aliyah would uproot my life and my family’s life entirely, as well as be an abandonment of my aging parents.

Instead, I have chosen to engage myself more in traditional Jewish practice, to build a Jewish home, to raise my kids as educated Jews here in Colorado. But it is not easy, as I am a religious minority in a part of the state without a significant Jewish community or infrastructure. I spend copious amounts of time and money trying to augment this reality, and I see little to no support from Israel for my endeavors.

I have been married long enough to know that any relationship that is built on love, and sustains itself for many years, needs to be also one of trust, empathy and compassion. Does that exist between Israeli and American Jews? I would argue not, the reason being that there are few opportunities for interaction or education. The expectation is that American Jews will do it all, but if the center of the Jewish world is the Jewish state, and Israel wants Jewishly engaged and literate Jews, why aren’t they doing anything to promote that result? Why aren’t there more Jewish Agency ambassadors in more areas of Colorado? Why is there not a free Modern Hebrew language program anywhere? Why is the issue of funding for Jewish day school, religious school and rabbinic school tuition, synagogue dues, summer camp, and b’nei mitzvah tutoring not being addressed? Why is there no one in the Israeli government working on confronting growing antisemitism and security concerns in Jewish communities? Why are we just left on our own, adrift, and mocked, ridiculed and ignored?

Why can’t Israel throw us liberal Jews a bone? Enact the Kotel compromise, deal with the issues of conversion and agunot and religious fundamentalism. See what happens when we are valued and our concerns addressed.

Enough with the berating. What does sufficient “support of Israel” look like from us, exactly? If supporting the protestors against judicial reform is not enough, what is? Donating more money? Visiting more often? Making Aliyah?

I say this with deep love and appreciation of Israel, an ardent, lifelong Zionist: I would really like to know.

1) Most American Jews are politically and religiously moderate (atheist/reform/conservative; Democrat/Leftist) Ashkenazim. Israel was founded and mostly populated by the same people. Part of the divide now is that Israel has shifted demographically, with a much larger number of Mizrahi and Orthodox/Haredim. American Jews don't have much of a framework for understanding those peoples viewpoints and values.

2) Most American Jews (at least in my experience), were taught to love and support Israel. But, it is hard to separate a country from its people. My experience with many Israelis (not all!) has been a fairly consistent arrogance and failure to appreciate American Jewry. From the secular types we hear "you don't understand israel, so don't criticize or even question". From the the religious we hear "you aren't really practicing Judaism, and we're not even sure you're Jewish". But from all, we hear "support us, give money, talk to your representatives, and, if you don't, you're a self hating Jew."

3) Jews are a family, but, like with many families, people grow apart, the love becomes attenuated. Individual families have broken apart over politics; so too can the Jewish family.

4) Many American Jews are alienated from their own communities over politics as well; synagogues have become places of open partisanship, with little room for difference of opinion, let alone room for the practice of Judaism for community and transcendence, rather than a vague sense of universalism. This further alienates many of us from connection to Israel.

5) For 2000 years we loved Israel as a concept; as with any consummated love, the reality is far from the dream.

Nuf' said