Why is the word "democracy" not in Israel's Declaration of Independence?

And what does schnitzel have to do with it?

Valeria Matalitza’s name is not likely to appear in the international press. But she’s made it into some small articles in Israel’s Hebrew newspapers—because she sued a schnitzel restaurant—and lost.

Why did she sue? She applied to work in a schnitzel restaurant in the city of Karmiel, in the Galilee. The proprietor told Valeria that she couldn’t hire her because the rabbinate of Karmiel, which issues the local kashrut certificates, has stipulated that if a restaurant hires a non-Jewish worker to cook, the restaurant must also hire a full-time kashrut supervisor to be present whenever the restaurant is open.

Matalitza is of Russian descent, so in all likelihood is one of the hundreds of thousands of Israelis who were allowed to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return, which grants such permission to anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent, even though she is technically not Jewish according to halakhah (Jewish law). Matalitza argued before the Labor Court that not being hired because she is not technically Jewish constituted a violation of her rights to equal access to employment. The restaurant’s defense was they would have liked very much to hire her, but they obviously couldn’t if doing so would mean having to employ a full-time kashrut supervisor in addition.

The court dismissed the suit. The restaurant was between a rock and a hard place, it ruled, and the real problem was not with the owner, but with the rabbinate. The Karmiel rabbinate, it noted, is much stricter about such matters than the Chief Rabbinate or the rabbis of other cities, which are more lax on such matters. But that was no reason to punish the restaurant.

Among the many initiatives of Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s government is reform of the rabbinate’s stranglehold over some dimensions of Israeli life. Just as it had to be a right-wing Prime Minister (Menachem Begin) who would be the first to cede territory to a former enemy (Egypt) in exchange for peace, Israel may well have needed its first Orthodox Prime Minister before it could tackle this issue. (Of course, the fact that the Haredim are not part of the coalition is also critically important.)

Admittedly, the religious reforms being advocated by Matan Kahana, the Minister of Religious Affairs, will not impact the recognition of non-Orthodox conversions or a host of other issues important to many Jews around the world. But these initiatives will, if passed, make a difference inside Israel as they recalibrate some of the imbalances in power between Israel’s religious authorities and its secular political bodies, imposing national standards instead of local standards for kashrut, allowing other organizations to use the word “kosher” in their supervision (illegal thus far), easing the process of conversion, and more.

That, of course, is enraging the Haredim and the religious right. Newspapers are filled with ads condemning Bennett as being anti-religious (though this photograph of him in his Washington, DC hotel in August somewhat belies that claim),

while others, even within the Orthodox establishment are applauding Bennett and Kahana, urging them not to back down.

At stake, in some ways, is the kind of democracy Israel is going to be. How should a democracy balance the rights of workers, for example, with the authority of the rabbinate to set kashrut standards?

What would Israel look like if it were up to the more extreme elements of the religious spectrum? We have a bit of indication from proposed drafts of a constitution.

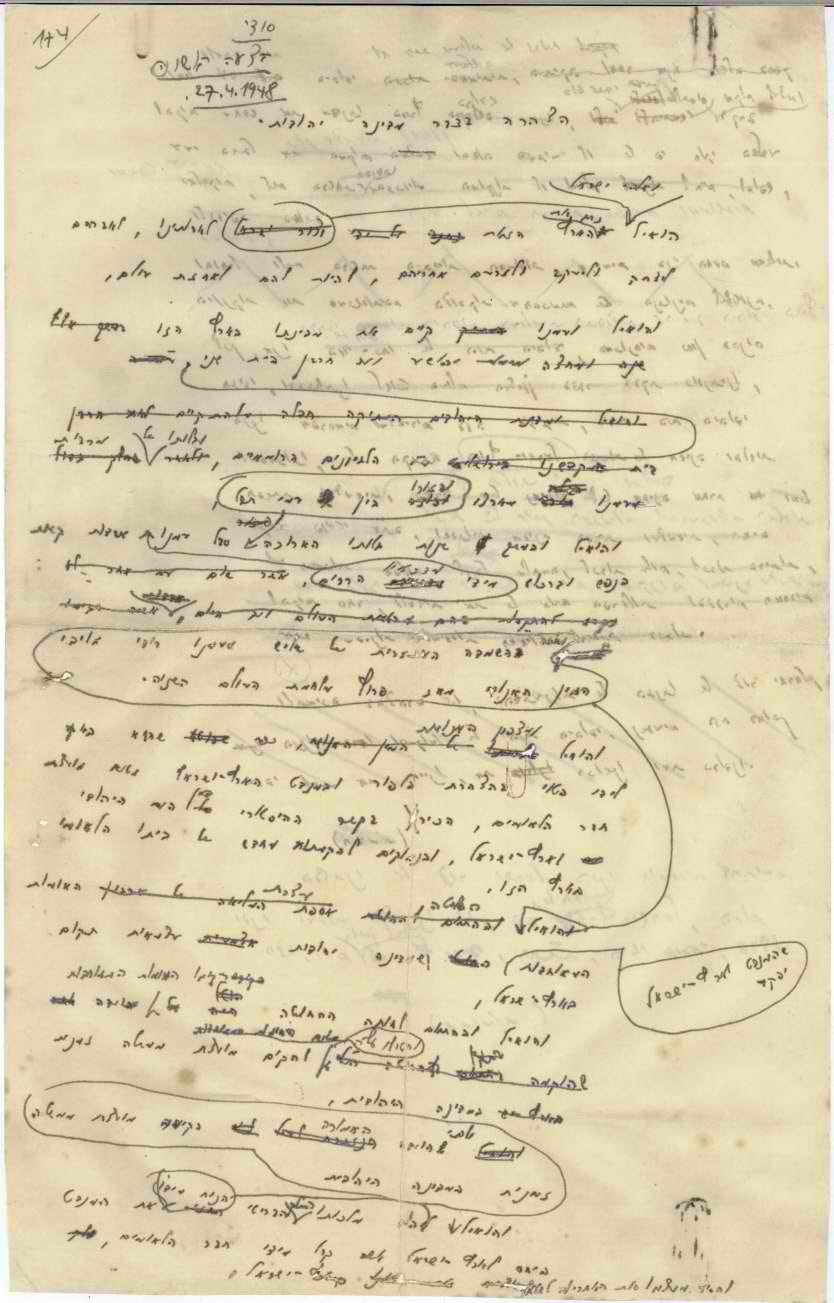

As early as 1937, the year that the Peel Commission advocated the partition of Palestine into two states, it was appearing more likely (or less unlikely?) that a Jewish state would eventually come to be. Some leaders of the Haredi community foresaw this, and made clear how they believed it should be run. Here, for example, is a small segment of a proposed constitution for the future state by Rabbi Moshe Blau (1885-1946), then a leader of the Haredi community in Palestine:1

Principles: [A:] the Jewish State recognizes the authority of the Torah in public life. …. [B] Authority for interpreting this principle will rest with the Chief Rabbinate of Israel; [C] The following religious principles are expressly part of the Constitution of the state: [1] The law will forbid any Jew residing in the Jewish state from performing the following activities on Shabbat: (a) To open a store, business, factory, office, theater, movie-house, (b) to travel or to transport anyone in public areas by train, public bus, private automobile, horse-drawn carriage, bicycle, etc.

Israel, founded overwhelmingly by secular Jews, was never going to adopt a constitution of that sort (it never adopted any constitution of any sort, of course). If what those rabbis wanted was something akin to what we see today in Iran, what Ben-Gurion and his fellow secular founders sought was something much closer to the norm in the west, a democratic state that would be deeply rooted in Jewish tradition, but still, first and foremost, a democracy.

Yet if that is the case, why did David Ben-Gurion, the arch-secularist who purposely did not wear a kippah at the declaration of the state, purposely delete the word “democratic” from drafts of Israel’s Declaration of Independence?

As we saw in an earlier column, “How Thomas Jefferson and a Conservative Rabbi helped write Israel's Declaration of Independence,” the job of drafting Israel’s Declaration of Independence was first assigned to a brilliant young jurist, Mordechai Beham. Beham began by studying and copying sections of the American Declaration of Independence, and largely based his first draft on Jefferson’s language. By 1948, it was more than obvious that the United States was the world’s foremost democracy; and if Jefferson’s text did not include the word “democratic,” one can easily see why Beham might believe that Israel’s need not include it either.

Basing his text so closely on Jefferson’s must surely have been sufficient to indicate that Israel was to be a democracy, no?

Not really, though, because the (largely suspicious) eyes of the world were closely focused on what Israel would say and do. The UN’s Resolution 181 specifically required an array of commitments from the still-to-be-formed state, and it included the word “democratic” three times. Therefore, when Beham’s draft was passed on to Zvi Berenson (then the General Council of the Histadrut, to this day Israel’s largest labor union and eventually a justice of the Supreme Court), Berenson added “democratic.” His proposed text defined the emerging Jewish state as “a free, independent and democratic Jewish state.”

When Beham and two associates got the draft back for reworking, they moved “democratic” to a different location in the text, but they left it in. Presumably, they agreed that Jefferson’s ghost was insufficient, that 1948 was a very different time than 1776, and certain things needed to be stated explicitly.

The numerous permutations of the text between Beham’s second edit and Ben-Gurion’s final word-smithing just before May 14, 1948 are too complex for this space. For the most part, though, “democratic” stayed in, and in most drafts, Israel was defined as a “Jewish and democratic” state. Then, though, Ben-Gurion excised it, and the Declaration was finalized without it.

Why, though? There can be no doubt that Ben-Gurion was deeply committed to Israel’s being a democracy. The Zionist movement had been democratic from its earliest beginnings at the First Zionist Congress in 1897, and by 1898, the Second Zionist Congress, women were voting and running for office, long before they could in any European country. For decades, Ben-Gurion had been at the helm of the democratic institutions of the yishuv, the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine.

Why, then, the objection to “democratic”? It’s not simply that Ben-Gurion didn’t put it in; he consciously took it out.

At the time, “the old man” (he was called that long before he was old) offered no explanation. But not long thereafter, in September, he wrote in his diary:2

As for western democracy, I’m for Jewish democracy. “Western” doesn’t suffice. Being a Jew is not simply a biological fact, but … also matter of morals, ethics. … The value of life and human freedom are, for us, more deeply embedded thanks to the biblical prophets than western democracy. … I would like our future to be founded on prophetic ethics (man created in the image of God, love your neighbor as yourself—these foster an egalitarian life as in the kibbutz), on cutting edge science and technology.

But that isn’t really a fully satisfying answer, is it? Why slash “democratic”?

We can’t be certain. To be sure, Ben-Gurion, whose love for the Bible is now the stuff of legends, probably did prefer Amos and Isaiah as inspirations to Thomas Jefferson.

But there was more. “Democracy” was a western notion, and in 1948, Ben-Gurion was cultivating relationships with both the US and the USSR (which had voted in favor of Resolution 181). Was he trying not to antagonize the Soviets?

And, of course, in May 1948, Ben-Gurion understood that Israel, once it came to be, was hardly going to have Canada as a neighbor. Israel would emerge from the crucible of war, and difficult decisions were going to be made. What if (as happened) Israel were to decide to put Israeli Arabs under military, rather than civilian, authority (it abolished that policy in 1966)? Might using the term “democratic” open Israel up to the challenge it could therefore not define itself as Jewish? And could a “real” democracy give a preferred role to one particular religion?

The country he was founding, Ben-Gurion understood, was going to be a creation unlike any other. There was what to learn from America, to be sure, but Israel was never intended to be a miniature America. Israel would be a country with a different purpose.

If America was to be devoted to “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” Israel was going to be about healing, protecting and cultivating the flourishing of the Jewish people.

The place to insert “democratic,” were it to have remained, would have been Paragraph 13 of the Declaration, which reads, in part:

it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

But Ben-Gurion wouldn’t have it. By deleting it, he was proclaiming that the state he was about declare would have a purpose—and a character—unlike any state the world had seen.

That, in fact, was the whole point.

A few months ago, on a Shabbat afternoon, I was reading A. B. Yehoshua’s novel, The Tunnel. In the novel, Yehoshua mentions an organization called “Road to Recovery,” through which, he said, volunteers meet Palestinians who are entering Israel for medical care at checkpoints, drive them to the hospitals to which they need to get, and then another volunteer picks them up and drives them back to the checkpoint.

I’d never heard of “Road to Recovery,” and wasn’t entirely certain if it was real or a creation of Yehoshua’s fiction. So after Shabbat, I checked, and sure enough, it does exist. And what it does is truly astounding. In 2019 alone, “Road to Recovery” volunteers drove 1,260,000 km, encompassing 10,105 trips and catering to 20,000 patients, mostly children.

I met with two volunteers from the organization, Alona Abt and Myron Yehoshua (pictured below). Alona, secular, is among the leaders of the organization, while Myron, religious and a resident of a “settlement” south of Jerusalem, is a volunteer driver. I found them fascinating and inspiring, and hope you will, too.

Here’s an excerpt of our conversation; the full episode will be uploaded for subscribers on Thursday.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Israel Dov Elbaum, Megilat Ha’Atzmaut — The Declaration of Independence with an Israeli Talmudic Commentary [in Hebrew] (Yediot Ahronot and Chemed Books, 2019), page 395.

David Ben-Gurion diary, entry from September 14, 1948. Ben-Gurion Archive. Quoted in Elbaum, above, page 423.