It is difficult, in these turbulent times, to focus on almost anything Israel-related that is not somehow connected to the current explosive political situation.

But we have to. After all, preserving Israel is not about preserving a Jewish state for its own sake, but because a Jewish state makes certain kinds of Jewish life, certain forms of Jewish richness, possible. If it didn’t do that, it would not matter very much.

In Monday’s column, we turned our attention to a notable Israeli annual photography exhibition. Today we turn to a library.

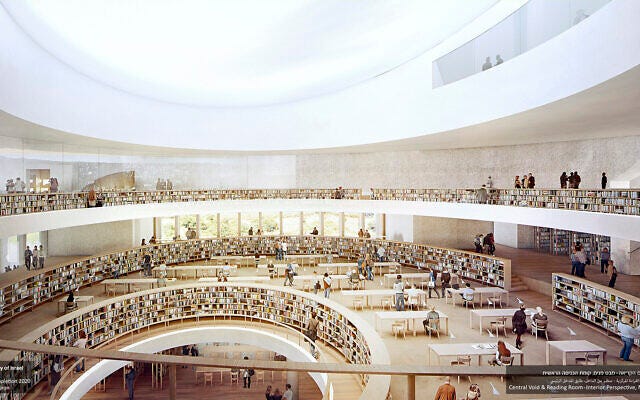

“A library?”, you might ask. Yes, a library. If you drive anywhere near the Knesset, the Israel Museum, the government center in Jerusalem, you cannot help but notice the extraordinary edifice now nearing completion, the building that will soon be home to the National Library of Israel. It’s not open yet, but I had an opportunity to get a tour of what’s being built. (We’ve posted a few of the photos that I took, below.) It is so extraordinary, so breathtaking and so reflective of the greatness of Israel that any look at “Israel from the Inside” simply my take note.

And the next time you visit, the new home of the National Library of Israel must be on your itinerary.

Until then, though, we learn about how the NLI was formed, what role a “national library” plays in a Jewish state and what the new NLI home will make possible in a conversation with Dr. Raquel Ukeles.

Raquel Ukeles, Ph.D., is the Head of Collections of the National Library of Israel; from 2010-2020, she was Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection. Ukeles received her BA from Princeton (1993) and MA and Ph.D. from Harvard University in 2006, all in comparative Islamic and Jewish studies. She also studied Jewish law in Jerusalem and New York, and Islamic law and Arabic in Egypt, Morocco and the Netherlands. She has published and taught on a wide array of subjects related to comparative Jewish and Islamic traditions, medieval Islamic law, the history of Islamic manuscripts, Jewish intellectual history under Islam, Arab culture in Mandatory Palestine, and creating a shared society in Israel today. She currently lives in Jerusalem with her husband and three children.

Dr. Ukeles walked us through the evolution of the National Library of Israel, from its establishment and early days at the Hebrew University campus to its new symbolic location next to the Knesset and the Israel Museum.

The link above will take you to our conversation, and a transcript follows below.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

We have been doing a tremendous amount of conversations recently about the complexity of Israeli political judicial life. We've been talking about the judicial reform. We've been talking to people who are in favor of it. We've been talking to people who are opposed to it. We've been talking about the new coalition. But Israel from the Inside, as our long-term listeners know, has always been about a much bigger picture of Israel. It's been about an Israel that is not just security and politics, but in Israel that is art and literature and music and history and men and women and Jews and Arabs and religious and secular and all of that. And people who go back in the archive and look and see all the conversations that we've done now over the last couple of years will see that.

Anybody who lives in Jerusalem knows that there's this enormous building that's been built in what we call kind of the Government Center area. Kiryat Hamemshala, which is across the street from the Knesset, kind of caddy corner to the Israel Museum, sort of across the street from the Bible Lands Museum, an enormous edifice going up which everybody knew was the National Library. And if you're driving out of the city to get to the highway via Sderot Herzl, you drive by it, you see a big construction site, and you say, oh, that's cool, and that's that. But I had occasioned a few weeks ago to be going to a meeting in the Knesset, which means that you go up the other side of the street and see the building. And then for some reason I said, “Wow, this building is almost done. This is huge. It's beautiful”. There's incredibly interesting shaped windows on the side that I was trying to figure out what they meant, and I Googled it and found out we can talk about that. And it struck me that this is a national treasure that listeners should know about. The National Library of Israel, https://www.nli.org.il/, for those of you that want to check out the really excellent website, is about to have a new home sometime, I guess in the next half a year, I'm not quite sure when. It's right across the street from the Knesset, right across the street from the Israel Museum. It's always been a venerable institution, but now it's a visible, open, venerable institution. And to learn more about it, to hear about its role in Israeli society. I invited Dr. Raquel Ukeles, who is the head of collections at the library, to tell us about the institution, about where it comes from, what it's doing now, what its plans are and why those of you who are not Israeli should definitely come and see it next time you're here. Because the building is stunning. Raquel, as you know, I got to take a little bit of a hard hat tour a couple of weeks ago and to see it almost done, it's unbelievable. So, first of all, thank you very much for taking the time to be with us. And tell us a little bit, first of all, just the history of the library. I mean, do most countries have national libraries? I don't even know the answer to that question. And how did Israel's national library get started and when?

The story of national libraries is fascinating because a library is something that you don't really spend a lot of time thinking about, frankly, until you work there. I was a user of libraries through many, many years of education, and I never gave it a second thought. I only cared about whether the book was there or the material I needed was there and if there was a good comfy chair. But it turns out that national libraries are very much a reflection of broader forces in society. A lot of national libraries in Europe were founded in parallel to national movements. Many of them started as royal libraries that were taken over, whether forcefully or less so. And it goes back to the function of a library as a symbol of power and wealth actually. And it wasn't about open access, the opposite. A person would cultivate a library as a sign of prestige, as a sign of authority or power, or, you know, in many cases with scholarly classes both in Europe and in the Islamic world as an elite society who had access to knowledge. And then starting in about the 18th century, you see the rise of these national libraries into the 19th century and so national libraries are actually pretty modern.

Where did they start?

They started in Europe. I believe France was the first, but I could be wrong.

And then obviously England has an enormous library.

Well, it's interesting about England because the British Library only dates to the 1970s. It was part of the British Museum, as an independent institution. But of course, it's the largest library in the world and has, I think, over 100 million items. It's in a league of its own, followed by the Library of Congress. Library of Congress is actually not a real national library because it's a library that primarily serves Congress and over time has become a de facto national library. But even though we're in this digital age, of Google and access to the whole world in your cell phone, national libraries have had a comeback. I think the digital revolution caused this terrible identity crisis for libraries, especially among librarians who were gatekeepers of knowledge, and why do you need a librarian anymore? And you saw this great creativity happening in libraries of transforming the library to be a place that was kind of a public square, a center of culture. I think a lot about the role of the New York Public Library as this tremendously inspiring place because they had this vision of belonging to the public, right? So, if the earliest library is actually Ashurbanipal in ancient Mesopotamia, where the library was very much for the king, all the way to the model of the public library, even more than the National Library, which was a place, an open, engaging place where anyone can go and borrow a book and learn and grow.

Okay, so let's just stop there for a second. And I do want to come back to the history of the National Library of Israel, but you talked about power, and you talked about how it's for the public. I guess there were probably some people who were perplexed by the location of this library, which is right across the street from the Knesset. And the Knesset is obviously a seat of power. People could say it's the seat of a lot of other things too, but we won't go there right now. And it's, of course, surrounded by rings of fences and security and so on and so forth. So, I guess somebody might argue, well, if a library is meant to be for the public, and it's meant to be a public square and a center of culture and openness and so forth, isn't across the street from the Knesset exactly the wrong place to put the library? I don't think it is. I don't think you think it is. But why is it not the wrong place?

So, the truth is, when I first learned about the new location of the library, and when I first joined the National Library in the end of 2010, I also had those concerns. I was particularly concerned about protecting the library's very important role in society as a bastion of freedom of expression and of pluralism, because a library can encompass endless narratives and endless points of view. But over time, I have come to believe that it's a very powerful, profound statement, both in terms of what's the value of books, of learning, of texts, of culture in Israeli society to get such prime real estate. And I also have a hope, and maybe it's a little idealistic that the members of the Knesset will look across the way to the library, and it will remind them of what the ultimate aims are, because the ultimate aim of politics should be a thriving society. And so, the library is the end in a way, but it’s also the means and the end, because the library is this place that belongs to everyone that is an opportunity for endless curiosity and learning and growing of deepening your own connection to yourself and with a little curiosity, learning about others. I always feel that if someone walks into the library looking for their own roots or their own seminar paper or their own journalistic assignment, and their eye gets caught by something else, and they browse, they follow the thread, and they come out having learned something. That's it. We've done our work.

Right. So, I want to come back to that in a second. Give us, in a very quick paragraph, the history of the National Library of Israel. When did it get started? How did it get started? Who started it?

So, what's interesting about the history of the library is that it predates the state by many decades. And so, it's different from other national libraries where the library came out of a national movement or a nation state. In this case, the National Library is actually perhaps the oldest public institution affiliated with the state of Israel. The crazy idea of a national library starts in the 1860s and 70s, and it was thrown about in discussions in Jewish newspapers both in Europe and in this land as this crazy idea because it turns out that Jews….

This is by the way before there’s a National Zionist Congress, right?

Right.

The Zionist Congress, 1897.

That's right.

So, you're saying 15 years before, there was a thought about making a country, there was a national library.

No, it was about making a library. It started with making a library as a place to gather and ingathering not of the people but of the books, of the treasures of the great fruits of Jewish literature. Now, it was a group of individuals, intellectuals.

Living here or living in Europe?

Living in Europe and here. And there were a number of attempts to get one started that failed. And then in 1892…

So, five years before the Zionist Congress…

Right. They rented a very modest building. They filled it with all the works they could get their hands on and it was called actually Beit Hasfarim HaMidrash Abarbanel. Which is significant because it was the House of Study, named after Abarbanel.

Who was a medieval Jewish scholar.

Who was this medieval Jewish scholar and Jewish community leader who in 1492, made the excruciating decision to take his community into exile in order to survive. And 1892 is 400 years after 1492. And so, it was a kind of dafka in your face to Jewish history that the Jews are coming back into action. And so, the decision, the vision to build a library was part of the beginning of cultural Zionism that Jews have to reenter history. The Jews have to take an active role in their own fate. And this happens, as you said, five years before the Zionist Congress. And so, this modest library with a crazy ambitious vision started to gather books. And then here comes the hero of our story, and his name is Joseph Chasanowich, who was a doctor from Białystok. And he was obsessed with this idea. He was so obsessed that he started taking books instead of payment for his medical services. He was living in Białystok, traveling all around what is Ukraine of today and Russia. And he started encouraging others to get on board with his crazy idea. He came here in the 1890s and he then wrote this manifesto calling on the Jewish people to build this library, where it was a little elitist, to be honest, and it was about gathering the greatest fruits of Jewish literature. And he shipped over thousands of books over his lifetime, he shipped over 22,000 books, which was by far the largest collection. Now, that was one source. The other source was actually what we call the founder of modern Hebrew, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who also tried to start a library, not successfully, but his collection got adopted and brought into this, again, very modest building, very modest library, but with all these grand ideas. Now I'll speed up a few decades when the idea of a university was developed, the Hebrew University, which was the first university in this land.

The cornerstone was 1919, and it opened in 1925. And so, they adopted this library as by far the largest research library available. And the library pivoted to become what was called the Jewish National and University Library. It was kind of compromise of holding on to its early national roots and to become a full-fledged university of the library they hired this extraordinary scholar, Hugo Bergman, who was a philosopher France with Kafka and Broad and all different kinds of philosophers and artists and writers and encouraged them to bring over their collections. And he professionalized the library, and he turned it into a library that had several circles. And I want to take a minute to say those circles because they are a guidepost to us today. The first circle is the Jewish circle, right? And that is the original role of the library. The second circle is the land of Israel, broadly defined. And in fact, the first Arabic collection was brought into the library in 1924 as this transition from the original model to this much broader, almost universal model of the library. And then the third circle was humanities, philosophy, thought, literature. And those three circles actually carry the library to today. And for most of its history, that means the library was kind of a national library, but really a university library. And it was kind of a national library in the sense that the public was allowed to come,

But it wasn't inviting really…

It really wasn't inviting.

For those people that have studied at Hebrew University or did your junior year abroad, I mean, back in the old, old days, before you were on Mount Scopus, you were in the city campus called Givat Ram, which is where I was a lot when I was a junior year student here in the sixteen hundreds more or less. But anyway, you would walk in through the turnstiles and go through security, and the National Library was off to your right, but you had to go through security to get into the university campus. It was hardly like what we see now, which is this enormous, gorgeous building without a fence around it. We'll come back to that. So, there's really been a huge transformation by separating the library from the university, right? That's what's happened now the library is separated from the university?

Over the past decade plus, the library has done a 180 transformation, and it actually goes back to the 90s and this digital revolution and a recognition that the state of Israel deserves a national library, which were popping up all over the world. And so, the university, together with the government and some of the great stakeholders of a library, convened one committee after another, like good Zionists projects and after literally a decade of committees, they came to this bold conclusion that the library has to be reborn. And in order to be reborn, it has to leave campus, as you described. It has to get away from all of these gates and to build a new building. Now, of course, because we're in the digital revolution and at the time, I always say I was in college at the time, I remember my first email address, and we all thought we would become robots, right? And so, the new library, from the beginning, incorporated this very ambitious hybrid model of a physical and digital library, which you mentioned our website, and we have hundreds of millions of digital items available, open access for anyone from their living room, from their cell phone. And so, we went from all these different stages of a library, at some level, reflects many interesting changes in Israeli society. The library is a kind of microcosm of Israeli society.

How so?

Well, today we have this interesting balancing act of one can connect it to the Jewish and the democratic characters of this country. And so, we are both a national library of geographic space, and we are a national library of an ethnic people. We're one of the only national libraries in the world that has this dual mandate. And so, we have two national collections. We have the Judaica collection, which is we collect in tens of languages all over the world.

Just to give people an idea, how many items in the collection?

In the Judaica collection, a few million. We have about 4.6 million books. We have about 60 million archival pages. We have 20,000 manuscripts.

And a lot can be searched online now, right?

Yes, a lot can be searched online. We have massive digitization projects, which is really the way to serve the Jewish people and to serve the greater good and greater knowledge. But I was explaining that we have these two circles of these two national collections, right? And all the time the balancing act between the two of them. And we have a phenomenal Islam and Middle East collection which is a window to our neighborhood, a way of accessing the religion and culture of the Arab community, Arab population here in Israel, and a general humanities collection which is the window to the broader world with a focus on Western culture and all the different civilizations that have been in dialogue with these three other collections. And so how you balance between and among all these different stories and histories and cultures, I feel, is the great challenge, not just of the library, but the challenge of what we're facing today for all of its bumps and complexities. But it's extraordinarily interesting.

It's really fascinating. So, this new building is going up. I saw it, and from the inside and the out, it is breathtakingly beautiful. I mean, really breathtakingly beautiful. My dad was a kind of an aficionado of architecture. He really wanted to be an architect; I think. But, you know, back in those days, he decided to be a doctor. But I think he really would have loved to be an architect. No, he really had this love for art. And I just kept saying to my wife as we were going through the library building, I kept saying to her, oh, my God, my dad would have loved this. And she kept saying, you know what? He really would have been over the moon about this building. It's very hard visually but give people a sense of sort of what makes this building visually and architecturally so unique, both in terms of its style, its function. I know it's hard to do without images but give us a little bit of a sense of what's so spectacular about this building.

Sure. I have to start with the architects, Herzog de Meuron, who are today one of the world's leading architects. And they really are geniuses.

Right. By the way, everybody assumes because it's Herzog, either it's related to the winery or it must be Jewish, but neither is true. It's the Swiss firm, right?

Yes. They're in Basel, Switzerland.

And it's really worth, by the way, going to their website. It's Herzog. And then what's the other name?

de lowercase and then capital M-E-U-R-O-N.

De Meuron. It’s funny and I’ll just say to our listeners, after I did this tour and I heard about these architects about whom I knew absolutely nothing, of course, I went on their website. It's unbelievable what they've done. I mean, it's truly one work of genius after another. So, okay, the Israeli National Library using these non-Jewish Swiss architects. Go ahead.

And the first time they came to the site, they drew a scribble on a piece of paper that looks a little bit like a tornado. But they immediately, from their Swiss backgrounds, they come to the Middle East, and they immediately connect this library to a well and to the well of knowledge. And so, we have this first scribble from the first meeting, and you can see it today in the library. And so, the library has a very simple shape. They did that on purpose. They said they wanted schoolchildren to be able to draw the building. And so, it has a kind of swoop, which a little bit reminds us of a half pipe for skateboarders. As a mother of a skateboarder.

I have pictures of this, by the way, so on the web page where this podcast is, people can take a little bit of a look at this.

Great. At the top of the ceiling there's a huge sunroof, a circular open window that goes all the way down through almost all the floors. There are eleven floors, four up, seven down, seven underground. And you have one reading room that has a funnel shape, a kind of wellspring of knowledge that starts with the most open and almost casual use of a reading library space and going down to more and more serious, quieter spaces. So visually, the library is very open and airy.

It's surrounded by gardens. There are Mediterranean courtyards all over the place to allow you to stroll and think deep thoughts. And it was built in order to enable parallel use. That is, you can walk in, and you can go to the visitor center, and then you can go to the permanent exhibition and then the rotating exhibitions and come around and end up at the bookshop. Or you can be a reader and you can enter the reading room and you can decide how serious you are today, or do you want to find a room. There are many rooms where you can have a hevruta, you can have a class, a seminar, you can go to the cafe and have a casual chat with one of the leading scholars of Talmud or English literature. And then you can decide to walk out for a little while, come back in, wait for your books, use the digital materials. And so, it was built to allow for many different kinds of people to enjoy and appreciate the site. And of course, I forgot our youth wing. The library, over the last several years has grown a fabulous robust program for elementary school students, high school students, teachers. Actually, 40% of our educational programs are with the Arabic educational system, students and teachers. And so, we have a very inviting, agile space for young people to come. And in the daytime, it'll be for formal educational programs. In the afternoon, it will be for families to come. And so, it was built with tremendous thought and care into how this library will actually be used, and not just, as, you know, an icon. And I give these architects a tremendous amount of credit because they've they entered into dialogue with the library professionals in order to really understand all of these uses.

They actually went into dialogue with buildings, too. I mean, they went in… I saw this online, and then I saw it in person. To me, it’s breathtaking, it's meant to sort of evoke the wear and tear, the erosion of ancient Jewish and Jerusalem stone. Even though it's brand new, it's truly gorgeous. And then your notion of openness. One of the things that struck me was that there's a beautiful auditorium, seats, what, 400 ish people?

480 people.

And then at the bottom, on the back of the stage, there's this gigantic glass wall, which it was explained to me that it could either be opaque, in which case it's just a normal auditorium, or it can be transparent. So, people could actually be outside the building and watch the concert from the outside. So, people inside and outside could theoretically be watching a performance, a concert, or whatever, which, again, I think is kind of part of this, taking it out of the university from behind the turnstiles and the guards. And as we said, there's no fences around the library. It's such a stark contrast to the Knesset. And I don't say this in any way derisively. I mean, obviously you need a fence around the Knesset, and everybody understands that. But the Knesset is a very well protected building, and a lot of buildings in Jerusalem are very well protected buildings, including Hebrew University, which is right across the street. It's not easy to get in, whereas this library is just completely open, not a single fence, really. To me, it was really, very moving, and that stark contrast is moving. For the techies among our listeners, there's some unbelievable technological developments in this library. You want to share a couple of them?

I want to start with a very new initiative that we're so excited about, because I see it as a kind of the holy grail for library nerds and for the public eventually, and that is to develop machine learning techniques to decipher manuscripts and handwritten material and to turn them into a searchable text. Now, why is that the holy grail?

By the way, people who have never done this. When I did a little manuscript work back in the day in graduate school. These manuscripts are impossible to read. I mean, you sit there with a magnifying glass, it's very hard to tell where one letter starts, one letter ends. So just people should understand you're not looking at an old newspaper or an old typed script, which you're then digitizing. You're looking at something that you really can't make heads or tails of even if you know the language.

Right. And so, the library has manuscripts that go back to the 9th century. We have other material even further from the fifth century. From the 9th century, manuscripts actually were written all the way into the 20th century. And then we have archives. We have 1,500 archives, personal archives, and thousands of community archives. And so, any subject you want to touch, there's material that's available. But as you said, it's out of reach for most people. We have Martin Buber’s archive. Kafka's archive. We have one of the archives of Isaac Newton. We have just an extraordinary array of thinkers and writers and rabbis and scholars and communities from across the globe. And so, if you want to find your ancestors or you want to do a research project or you're just curious, this material is out of bounds for most people. It's very hard to access.

And it's all being digitized now, or a lot of it?

So, over the last decade and even more, we've been digitizing the material and using these advanced technological tools, we are slowly making this material searchable. So, there are two terms. One is OCR, optical character recognition. And that's become quite pervasive. And so, we have now about 6 million digital newspaper pages in about 24 languages. We have this extraordinary research called JPRESS, the Historical Jewish Press of, I think, 600 newspapers from around the Jewish world.

And anybody can access, anyone can access this.

Anyone can access this. It's very mobile and desktop and iPad, et cetera. And that has OCR. So, what does that mean? That just means to turn a PDF into a searchable text, which is amazing. And now we're working on this HTR, which is handwritten textual recognition, which will do the same for manuscripts and archives. Now we have digitized in another, I think these are the two most important contributions to the Jewish people that we have done JPRESS and what we call Kativ, which is the digital library of all Jewish manuscripts around the world, all Hebrew letter manuscripts around the world. The librarians worked since 1950. It actually goes back to David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister, over 1,200 institutions worldwide in order to make copies of their manuscripts. So that it used to be you would come to Jerusalem to this very wonky place named the Institute for Hebrew Microfilmed Manuscripts, and you would go and sit in one place to access manuscripts from all over the world. And then starting in, I think, 2013, we launched Kativ, which is a digital library of about 700 partners from around the world and today has cataloging information for over 90% of all known Hebrew manuscripts and scans of about 85%.

So, if there's an ancient manuscript at the Library of JTS, for example, on the Upper West Side of New York, theoretically one could read those manuscripts digitized on the National Library of Israel website?

Yes. Because often it it's on two institutions, because one of the great things about digital material is that it can be in more than one place. And it is sort of the antidote to any kind of territorial, the opposite of wanting to share. Today digital solutions allow us to share. I'll give you another example. YIVO, the great Yiddish center that actually started in Europe and moved to New York. The YIVO in the National Library salvaged and saved the archive of one of the 20th century's greatest Yiddish writers, Chaim Grada. For various reasons, it fell into a marginal status, and it was discovered, and we bought it together and we received it together, I'm sorry. And we paid for the digitization of the entire archive. And just this week, we are launching the digital platform of the Grada archive, which sits both on YIVO’s website and on the National Library's website. And I can go on and on.

Yeah, there's tons of stuff. And I just saw there's a great newsletter that comes out. How often does it come out? Once a week, I think.

Yeah, I think it comes out once a week.

Yes, I get it both in English and in Hebrew. It's actually fabulous.

There's also one in Arabic.

Okay. That one I don't read, unfortunately. I'll say with embarrassment.

Not too late.

Yeah, actually it is too late. We actually have great Arabic classes here at Shalem, and I've sat in a few of them and watched these 20-year-olds learn how to read a language in 2 seconds while I'm kind of breaking my teeth. So, I think it is too late, but unrelated. So, I think it was in this week's newsletter that talked about how the Jerusalem Talmud of Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky has been digitized. So, some people may have heard Rabbi Kanievsky, who was really one of the great Torah scholars, but became a little bit controversial during COVID because he became opposed to closing down schools and all that, but really one of the great 20th century Jewish, you know, Talmudic minds, his Jerusalem Talmud, his own personal copy with all of his notes in the marginal. It’s digitized. And I went on there and it was just fascinating. So, you have everything from Chaim Grada, who's this Yiddish authority, to Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky and obviously many others. So, we have the OCR, we have HTR, we have the whole searchable manuscripts.

There is also another piece that I thought was just unbelievable. I mean, obviously every library is deathly worried about fire, right? That's the mother of all fears. But the solution to fire is the second mother of all fears, which is the way to put out a fire is with water. And obviously, if your library burns, it's a disaster, but if your library gets soaked, it's also a disaster. So, the National Library of Israel’s new building has a very unique solution which makes fire impossible and water not necessary. How does it do it?

So, we have these automatic stacks, sort of like Amazon, where there are books and crates 20 meters high, and robots will bring you the book. And you can watch this from a window.

I watched it. It's unbelievable.

And the way that you prevent both fire and the sprinklers is that there's very little oxygen in the stacks. And so, because of robots, we've separated out the humans from the books. A human can go into the stacks for up to 4 hours, or you can turn back on the oxygen, which is what they've been doing while they set this up. But now there are over 4 million books in that area you saw, and they've turned down the oxygen. And so now the books are safe.

Right. So, somebody told me that if you go in there and you try to light a match, it just won't light.

It won't light.

There's just not enough oxygen for fire.

Right.

It's kind of astounding. And again, you mentioned it very briefly, but the robot thing, it's just hard to describe how unbelievably cool is. 20 meters is what is about 60ft, I guess 70ft high. So, we're talking a very, very tall set of shelves, and each shelf has these crates on it.

And every book is barcoded.

And they're not barcoded by subject. That's what I found mind boggling. It's entirely random.

It is a disruption of the traditional method.

Right. Now, if you grab the crate off the shelf, somehow it would have….

The whole world in your hands. All these four collections. And also, we have a phenomenal music collection that has a music library and so every crate will be a reflection of this extraordinary diversity of the library.

Still, the computer knows where each book is. So, you go online or even to the library, say, I want this book. Somehow this robot knows exactly which crate it's in, which is how high it is, which set of shelves, and it pulls the crate off the thing, brings it to actually, this part is done by a person. Right? The actual book is fished out of the crate by a human being?

Yes. For now.

For now. And then I'm told eventually the idea is that these little robots will take the book from there and bring it out to you in the reading room.

I mean, we joke about that. I don't know if it'll happen, but I did see it in the Gulf. There is a robot who mills around. It's more of like a reference source than bringing you your book.

The technology, the combination of the architecture and the technology and the depth of the collection and the openness and its proximity to the Knesset. It's really breathtaking. And people are always asking me, I'm coming to Jerusalem for the fifth time, 6th time, 12th time, 20th time, whatever. What do you suggest that I see that I haven't seen before? This has just got to be very high up on people's list, and we'll begin to wrap up. I'll just say I think I mentioned this to you before we got started, but I went to the library a couple of weeks ago. It was really, as I said, it was beautiful. It was breathtaking, it was inspiring. It also made me very sad. I have to say. I walked around with a really, really heavy feeling, because we're going through a tough time here in this country, and it's not 100% clear how this whole thing is going to play out. I'm trying very hard to be optimistic and assume that some compromise is on its way. Who knows? But I kept walking through the building and saying to myself, it's so heartbreaking. Look at the greatness that we're capable of. I mean, this teeny, little country which has done so many things amazingly. This library is the very, very best of what we're all about. The breadth of the collection, the depth of the collection, the physical beauty of the new surroundings, the vision at the heart of this, the ability to kind of slowly untangle it from a university which has its own needs and make it into a really open national institution. Then I kind of glanced across the street and looked at the Knesset, and I said to myself, you guys, you women, and men in that building, you got to get your act together because there is so much greatness in this country. Don't screw it up. I had this very sad feeling, but I think to end it, to come back to the positive sense, the Knesset is a complicated place right now, and it's always been a complicated place. It was never simple in the 1950s either. It's always been a complicated place. And I think for those who look at the Knesset and think oy and they go through 70 years of Israeli legislative history and all that, you can feel whatever you feel. And now right across the street to me, is exactly the opposite sort of vision. Universalism and particularism, living hand in hand, real, true greatness. I mean, really just greatness. Topnotch staff, top notch facility, world class collection. It's an opportunity for people, really, to see the greatness at the heart of the Zionist vision, isn't it?

I think it is. And I always take heart when I get a little despondent. I take heart in this plucky group of visionaries in the late 19th century who had none of what we have, but they had tremendous dreams and tremendous vision, and they understood that the Jews have always been the people of the book, and we've been through many, many hard times. But we are living in one of the most interesting chapters of Jewish history, and I'm not ready to say game over. I think that Israel will survive, and there's tremendous greatness here, and it's worth this great struggle. I want to mention at the end a wonderful phrase of the Jewish philosopher and thinker, Moshe Halbertal. He says, the National Library is the beit midrash, the House of Study. But it's more than the House of Study. It's the noisy place of dialogue and debate, of different positions of arguments, of really focusing and yelling and discussing intensively about what matters. And so, this pairing of the Knesset and the National Library, I think, in the end, is very optimistic. It speaks to the great content and the great building blocks that we have in our culture, both Jewish culture and actually in Islamic culture as well, and in the Middle East. And it also speaks to what are the challenges that we have to work on in our day, right? It's not for us to finish this work, but it is for us to do the work.

Right. And it's for us to leave the work to be done for the next generation. And what you guys are building now, both physically in terms of the building and internally, and what the content of the building is, you really are giving an extraordinary gift to the next generation of Israelis, to the next generation of Jews, to the next generation of human beings all over the world, no matter what their background. It's a real inspiration. I encourage our listeners to come and see it when it's open. And to you, Dr. Ukeles, I just want to thank you for your time. It's fabulous to have an opportunity to sit with you and to learn about the library and to have you share your passion for it.

Thank you so much.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Across the street from the Knesset, there's a building going up that has no fences—intentionally