THURSDAY (7/18): It’s been some six weeks since the heroic rescue of the four hostages—and the tragic death of Arnon Zemora in that battle. In classic Israeli fashion, people are rallying to support his wife and are sharing a unique project she’d begun long before the war. We’ll share the project, along with the window into Israeli life that it provides.

Noa Sorek is poet laureate of the Minister of Culture's award for poets in their early career. Her first book, Volition, was published this year by Pardes Publishing. Noa has a bachelor's degree in philosophy, Judaism and humanistic studies from Shalem College and a master's degree in Hebrew literature from Ben Gurion University. In addition to her intensive work as a poet, she is a content writer for Beit Avi Chai. Born in 1996 in Ofra, she is married to Nadav and lives in Jerusalem.

Below are a few of Noa’s poems that we read and discuss in today’s podcast. You can follow along with the recording by using the texts below. Credit for all the English translations: Amit Mishan.

The link at the top of this posting will take you to the full recording of our conversation; below is a transcript for those who prefer to read, available specially for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

The purpose of Israel from the Inside has always been to try to offer a window or a lens into the hearts and souls of Israelis of all different sorts. There are dozens of news sites and websites and other sources of information about politics and conflict and all the day to day goings on in the state of Israel. What we try to do is give people a little bit more of a sense of what it is that Israelis are laughing about, worrying about, praying for, thinking about, talking to each other about by looking at what's in the print news, sometimes what's online, sometimes what's in Israeli TV. We look at history, we look at literature, we look at art. And today we're going to look at poetry.

When Amanda Gorman spoke at President Joe Biden's inauguration some number of years ago, I think it was probably the first time that many Americans had heard a contemporary poet read one of her poems. And while that's obviously the case that rank-and-file Israelis are not walking around Israel all day long reading and speaking about poetry, I think that it is fair to say that poetry plays a much larger role in the cultural, intellectual and spiritual life of Israelis than it does among average Americans. The daily papers and their weekday editions have poetry written, sometimes by the same person, sometimes by different people. Poetry appears on Facebook, appears all over. And we are going to try to look into the heart and soul of Israelis today by meeting one of Israel's young and most recently published poets.

Noa Sorek was a student at Shalem College years ago, which is where I first met her, and her first book of poetry was just published. It's called “Haratzon”, which she translates in English as volition. And in our conversations today, she's going to speak to us about poetry in general, her life as a poet, and take us through three of her particular poems, two of which appear in the book and one of which is more recent and talks about events since the war. Again, a way of trying to understand what it is that Israelis are thinking about and wondering about. It's not easy to talk about poetry under any circumstances, and it's certainly very brave to talk about poetry in a language that is not one's native language. So, I'm very grateful to Noa for taking the time to teach us, to speak with us, to share with us her thoughts, and I'm delighted to share with you our conversation with her.

So, Noa, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to us about poetry, poetry, your poetry, and your new book. Your new book just came out. I'm holding it in my hand. It's gorgeous. “Haratzon.” Desire? How do you translate it?

I translated it, actually. It's inside. I translate it to “Volition”.

Volition.

Yeah.

Okay. Wow.

The simple translation would be “The Will”, but I didn't want it to be my last book.

Okay. It won't be your last book.

Yeah, but I think Volition captures, what I wanted to write there.

Okay, great. Anyway, so we're going to put a picture of the cover on, too. We're going to get to three poems that we're going to look at in a little while. But before we do that, I think Americans, the last time they met a young poet was at Joe Biden's inauguration, where this young woman spoke unbelievably beautifully, and she had a tremendous character, and she was obviously a full personality. But I really do think that it was the first time that a lot of the people, the millions and millions of people who watched the inauguration, had heard a poem in many, many years.

Israeli society is not like that. Israeli society, poetry plays a much more central role. I mean, if you open up Makor Rishon every week, then Erlich has his poems. If you open up Haaretz, they've got their poems. And poetry is an ongoing thing, and it's a long tradition since Natan Alterman used to write the “Hatur Hash'vii”, the Seventh Column, as he called it. So, there's a history of poetry in Israel.

But still, it's not every day that you sit down with somebody and say, oh, hi, what do you do? And the person says, oh, I'm a poet, and actually means it, and actually is one. So, my first question would be just tell us a little bit, I mean, I've known you for a very long time because you were a student at Shalem, but tell our listeners a little bit about you, how you grew up, how this poetry thing started. Did you know at five or 15 or 25?

So, first of all, I will say that in Israel, not only that you have poetry in newspapers and even in the streets, but you do also, I grew up on music that was like poets of poets, like Natan Alterman and La Goldberg, and it’s got a melody. This was a song that I was growing up on.

It's also interesting, by the way, that in Hebrew, the word for poem and the word for song is the same word.

That's true.

Which is also a very interesting social, we don't have a different word for poem or song.

Yeah. So, when I try to explain to people in Israel that I'm writing poetry, I have to say it in English. So, they will understand.

Right, because if you say “shirim” then they think you write songs.

Or maybe that I'm singing, which I'm not. So, I think poetry was always in the back of my mind. I saw it, I read it. I really grew up on songs that Leah Goldberg wrote.

She wrote poetry, and then somebody else wrote those songs.

Yeah, right.

There's a lot of those, right? I mean, even the Bialik, tons of Bialik songs that were put to me.

Kids grew up on Bialik. But I was actually in my high school. I was into art, but I went mostly to visual art. And then I started my national service in Eilat. I was a tour guide.

I saw it was 45 degrees in Eilat yesterday.

Yeah. And I still want to be there more than anywhere else.

Really? You still like it?

Yeah, I love Eilat very much. Then I was a tour guide, and I met a guy. That's how all the stories start. He was secular. I was religious back then. And we clicked and we started a relationship by phone because I was in Eilat, and he was anywhere else. And then we broke up before anything really happened. And I really wanted to keep any kind contact with him. And I couldn't because I knew I will never meet him by accident, even though Israel is so small. I'm religious young girl living Eilat, and he's a secular guy, lives in Shfela.

Shfela is the center sort of.

Yeah. We had no mutual friends at all. And my dad had Facebook, which I was kind of using, sometimes reading things in his Facebook. And then I decided to open mine. And I published in Facebook a poem, I wrote to this guy, kind of a way to tell him maybe we should try again.

Was it your first published poem?

Yeah. If you don't consider a poem I wrote when I was, I don't know, 10 years old in a kid's newspaper.

We'll put that as the preamble or the overture or something. Okay.

So, it was my first one.

So, you were in the army during this, so you were like 18, 19, 20? How old were you when you wrote this poem?

I wasn't in the army. I was in National Service.

Oh, you were in National Service, right.

Yeah. I was 18.

Eighteen. Okay.

I got nine likes from my uncles and…

But the poem didn't say anything about him, right?

No, it was to a guy, but nobody could know who I'm talking about. Yeah. So, my whole family reacted to my poem. I don't think they knew what it is about. And then I felt like this is the kind of conversation that I'm interested in, writing something and having people reading it and respond. And I used to write to myself always. Not exactly poems, but I did write. And then I started to write more poems, and it became a really long and interesting conversation between me and more and more people. And then I started to understand that this is something that really interested me. And I started to read more poetry. I always used to read some poetry, but I read some more, and I started to become friends with poets that explained to me some basic rules about poetry and about rhymes and rhythm. And I started to learn and to read more and more. Yeah, it became a thing.

Wow. And you started writing seriously? When were you starting actually to produce poems regularly?

So, it's never producing because it takes long time between one and….

What time did they come off the production> At what age were you starting to accumulate a pile of poems that you'd written, would you say? You wrote this guy a poem ,and I don't know if there's any more to that story or that was the end of that.

No. I met him last year, like a second time.

Nothing ever happened?

The only thing that happened is that after we met, he started to learn philosophy. Now he's in his MA in philosophy because of our meeting. I wrote a book, but we had nothing to do…

And did he ever see the poem?

In Facebook, yeah.

Did he know what was about him?

Some of them, yeah, I think he did.

He did know what was about him?

Yeah.

Okay. So, he has a place on the shelf somewhere. Okay. But at what point were you starting to work on poetry as a regular part of your life, would that say?

I think I understood something that this is become my main art I want to do quite early after I started.

Before you did your degree here?

Yeah.

So, when you came here, you're already writing poetry?

Yeah. And also, I already went to some poetry classes, and they met... I think my friends, my poet friends, have a lot to do with my poetry. I read them and they read me, and we commented on each other and I learned a lot from some of them. I think when people really started to read me, I understood that something really working. And then I started publishing in some newspapers. It took time.

Which one?

The first one was some youth newspaper. I just hate the poem I published there. Sorry. I put it on the side, but I published in the Hall, which is a main poetry... I don't know. It's not a newspaper.

It's like a journal, more.

Journal, yeah. Their focus is on in rhymes and rhythm. So, they're more classics. And my poetry went to this direction in some way during my writing. And also, Haaretz and Makor Rishon.

Which are two opposites by the way. People should understand Haaretz is the New York Times of Israel. It's the main intellectual newspaper, and it's left of center. Some people would say very left of center. That depends on who you ask. And Makor Rishon is kind of the right of center intellectual newspaper. I personally think it's also a fabulous newspaper, and culture stuff is unbelievable. And then again, people disagree. Is it right of center? Is it very right of center? It depends. There's lots of different voices in Makor Rishon. So, you've done Haaretz, you've done Makor Rishon.

So, let me ask you this. I mean, obviously, you're an artist. I'm assuming that a lot of these poems, you don't sit down at the desk and say, okay, I have to write a poem today, and you take a blank piece of paper or a blank screen on the computer, but something starts to bubble up. You're walking to go buy a thing of milk, or you're folding laundry, and something just comes up in your head. I think all of us who write have that whatever. It's an art, and it's part of your soul, and it bubbles up. There's that song in Hebrew, “eich s’nolad como tinok?”How does a song get born? It's like a baby. It starts inside, and then it comes out, and blah, blah.

But you're also writing now in an unbelievably fraught, complicated, ta'un, fraught is ta'un, a really fraught time in Israel. We're nine months into the war, which means that we're 18 months exactly, basically, since the first protests. The first protests started in January '23. So, we're nine months into the war. We're 18 months into the worst internal catastrophe that Israel has ever had that it has that we're still in the middle of.

Before we get to the poems, I just want to ask you, is there a social, not political, but is there a social agenda to these poems? Are you trying to create a dialogue about anything? Are you trying to speak to the Israeli people? Or is it simply art, and whoever reads it, reads it? Or is there something more that you're trying to do or say? And I think that will especially become an issue in our third poem that we look at.

Yeah. So, I think you can't really distinguish between both of these things because I don't believe in pure art. I don't think it exists. And I write about what bothers me. And when I live in Israel in this catastrophes, it is part of me. It is part of what bothers me and what I think about. And it is part of my life. So, when I write about it, I don't try to do it in a way that will, I don't know, go to the newspaper and pursue people to do things differently. I'm not a publicist, but I write my truth, and I hope people will read it and it will do something to them.

Because Ehrlich, and by the way, Alterman, back in his day, they were overtly political.

Yeah. But I think also Alterman, he had two hats.

He had two hats he wore, yeah.

One of them was the poet who was very classical and very artistic. The other one was much more political. I think people appreciate him for both sides, but mostly for his artistic part, because this was really the highest levels he got.

But the magash hakesef, for example, the silver platter.

So, he had his real classics. Absolutely.

Real classics. He has that one about the certificates that you need to be able to get into Israel. Some of his classics are really… Obviously, just blanking. Greenberg, right? Uri Tzvi Greenberg. Uri Tzvi Greenberg, also. I mean, very classic poet in certain ways, but a furious Zionism that comes out between the lines, too. So, I guess he has a hat and a half.

Yeah. So, I think Uri Tzvi Greenberg is interesting because he really, you can read his poets, like his early poets, about being a soldier in World War I. And he wrote about his horrible experiences and his traumas, and it's so personal. And then from there, he grew to write about Israeli politics, but it was part of the same thing for him. And also, I think part of my poems is not about politics per se, but it is about being a young woman in a religious community and about women's rights. Also, I don't write it as an essay. It is about my experiences, but it is part of something.

It's just great to talk to somebody whose art is so central to who they are. We're going to look at three poems. The first one is actually the first poem in your new book, and it's called, “Hibook” which means a hug. So, this translation, it's an approved, authorized translation by you and whoever helps you with the translations. But I'm just going to read it, and our listeners also have it on their screen. So, if they want to follow along afterwards. Then I'll just read it, and then talk to us about what it's about, what it's saying, what part of you it gives expression to. It's called “The Hug”.

And what happens when bird loves cage? What happens to wings that spread just almost, having limited space but a flap? What happens when cage loves bird becomes addicted to the wings brush against the golden iron, hugging gently a rapid captivated heart. And what happens when the base of the wing starts to hurt? When food is no longer enough, what happens when the base of the wing starts to hurt, when food is no longer enough? What happens when a bird is free imminently? But cage does not let go. What happens when bird cheats on cage with a branch in a window or a clear blue sky? What happens when bird is drenched in the rain and has nowhere to but a branch? What happens when a hug has to let go? What happens?

Okay, it's very musical. In the Hebrew, especially, it's hard always to translate poetry, but it's really very musical. It has a rhythm. So, talk to us about this hug.

This is the first time I'm thinking about it, but I think maybe this is my first poem in the book because it is... I don't know if it's the first, but it's one of the first poems I wrote that really are about volition, about will. I think the story behind this poem is not the interesting part, but I think it's this feeling that something is good for you, but still not enough. And it's a feeling of wanting more. I think growing up, one of the feelings I think a lot of young people feel is that there is something bigger outside.

There has to be something bigger.

There has to be, yeah. So, we grew up in some systems, and we go to school, and then we go to... In Israel, we go to National Service or the army.

We're in a family.

And of course, our family. And there is this urge to do something more and to look for something bigger. But it's also dangerous because when you go out, so you don't always have where to... How to go back and you…

Right, Shlomo Artzi has a similar, his song “Oof gozal,” a little baby bird. I don't know what the English word is. Chick, I guess, whatever it's called, to take off out of the nest and fly. It's a very similar That's a good idea. The bird loves the cage. The cage is the system kind of?

Yeah, I think so.

The bird knows there's something outside of the cage, but it also wants the protection of the cage.

Yeah. And also, I think it's more than protection. It's also real love. I did love the places I've been to and the places I grew up in and the systems I was part of. I really did love them. It wasn't against them, but it wasn't enough.

For example, growing up as a woman in a religious community, I would imagine, for example.

Absolutely.

Right. So, what happens when the cage loves a bird? But here the cage loves the bird, too, right?

In other words, it is a relationship.

It's a relationship. They meet each other. So, how's the branch cheating? That was the part that I wasn't sure I understood.

I don't know if it works in translation, but it is like the bird is cheating with a branch. She's cheating on the cage with a branch.

Right. She's cheating on the cage with a branch. So, she’s in the cage and…

And she wants to go out.

She wants to go out, but she sees the branch. She doesn't hold the branch. She can't touch the branch because she's in the cage. So, the branch is outside. So, she's cheating in her mind. Is that the idea?

I feel like all cheatings are in mind.

Well, I'm not sure that all marriages that broke up over that would agree, but that's a separate conversation. I mean, it can start in the mind, but whatever. But yes.

I think it's mostly about what you're looking for.

Why is it cheating more than longing?

Because you have the cage, and you have a good relationship with it.

So, there's something almost by definition, boged, when you say in Hebrew that a person cheated on their spouse, we don't say cheated, we say, which in English means they... Betrayal. You don't say he cheated on his wife, you say he betrayed his wife. But that's a very strong... Cheating is, I don't know, you start over the line a little bit when you're having a race or something. But to betray something is much deeper. I think the Hebrew captures it much better. So, it's betrayal because loving the branch or wanting the branch or yearning for the branch is already a violation of that mutual love. So, by definition, volition almost has built into it, betrayal.

I think it is. Yeah. I think it is correct for everybody, I think, because our will is mostly, it can't work perfectly with everything in our life. And if we really stand up for our volition, our will, so we will have to betray some things, I think. And also, I think it comes back to being a woman and to growing up as a religious woman, that your will is not the most important thing.

It's true for a religious man also.

Yeah, absolutely. I think it's really true for everybody who grew up in society, any society. I think also, I wrote it, this is one of my first poems.

You were how old approximately when you wrote it?

19.

Oh, so that's really young to be writing about volition, will and betrayal. But okay.

Yeah. I didn't know it is about volition, but I think it was. I think it's also like when you're young, you can't really follow your will because you have, you’re in a system…

Yeah, you’re in national service. You're a daughter to parents. Right. Wow. Okay. We can talk about this forever, at least I can talk about this forever. But let's go on. I want to do two more poems with you, one of which, again, has an official translation. And again, I'll read it and we'll put it up.

The translations are by Amit Mishan, who did a good job.

And then the third one we'll talk about. Okay, so this is “A Poem Owing To The Geocentric Model.” Sounds very scientific. But okay.

In the morning, I circle boundaries around me in the dry sand. In the evening, I pray for you to dissolve them when you wash home. You are but a kiss away, but a whisper away, yet immersed in a different space, dreaming things you'll forget in the morning, things I'll never know about you that you think are too insignificant for me to know. I want to wake you up to say that it's good that you're sleeping next to me, that all the minutes have gone by in void since you fell asleep. Now in bed, when you're breathing long and slow, we are the center of mass. And maybe that means that Copernicus never knew what love is, or at least never rented a house with it.

I love those last lines, but let's talk about the poem in general before we get to Copernicus. So, first of all, just so everybody understands, what did Copernicus say that doesn't fit this model here?

Copernicus said that the Earth goes around the sun and not the other way.

So, he said the Earth goes around the sun. It used to be thought that the sun run around the Earth because the Earth feels still. See the sun rising, you see the sun setting. Sun's not rising or setting. We're just moving around it. Okay. That we all know. So, he said that the sun is at the center. Okay, so we'll come back to then what's anti-Copernican.

Yeah. Actually, I love Copernicus a lot, and I believe he's right.

Well, obviously, he's right.

But I think that the geo-centric model is about, I don't know, feeling that the ground is really stable, and things are really in their place, and nothing moves. And I think it's also... it’s not by accident that people believe that the sun is going around them in the opposite way, not only because they felt stable, but also because we think that things are... We are the center of the world, and everything is happening around us. And I think this is a love poem to my loved one, Nadav…

Who happens to be your husband.

Who happens to be my husband. I don't love this It's a word, but yeah.

Okay, it happens to be your partner.

My partner. And the book is also dedicated to him.

He's also a writer, we should just say.

He is. He is a writer. He's a poet.

A lot of typing in that house, I guess.

A lot of books also.

I would imagine.

Yeah. And I think this is part of what love feels like. You two are the center of your world and that you have stability and things don't move. Things move around you, and you are in your place. And this is why I wrote it. Maybe Copernicus didn't know what love is if he felt like we are going around the sun.

There's a different center of the world.

Yeah.

So, if he didn't ever feel that he was the center of the world, then he didn't know what love is. Okay, and then just let's talk for a minute about at least, I love the line, at least never are rented a house with it. What's the Hebrew? He didn't rent a house with love, meaning he paid for the house with love, or he didn't rent a house that had love in it. It could be either way.

When you're a young person in Israel, there is no option of buying a house. It is between renting a house or living on the streets. It was my studently way to say, you live together with your love. You rent a house with it. This is the most far you can go.

Okay, so “may'olam lo yada ahava”. He never knew what love was, or at least he never rented a house with it.

Yeah, with his love.

With the person that he loved?

Yeah.

Okay. So, it's not that the currency for paying for the rent is love. Because the Hebrew and the English could both be understood that way.

That's true.

“Who sachar et habayit im ahava. You can say, he rented the house with shekels. But you're saying, no, he rented a house with the one that he loved. And had he done that, he would have thought that he was the center of the earth, not the not the sun, being the center of the earth.

So, there is something here. I mean, it's interesting because it's obviously, it's a completely universal poem in almost every way. I mean, everybody who's ever loved somebody has been awake next to them and watched them breathe and been deeply grateful that that they're breathing and deeply grateful that they're there and sometimes terrified by the understanding that they won't always be breathing. I mean, so it's both unbelievably filling and terrifying. Love is terrifying at the same time as it fills you. It's totally terrifying in a way that you don't want to live without, but you want to be terrified, right? Or it's the price of love, perhaps.

So, it's a universal poem, and anybody that's been in love could relate to it beautifully. But there is this little Israeli shtuch at the end. So, you're saying, because it's a huge issue in Israeli society, that housing here is just too expensive for young people to afford.

I never thought about it. It was like, it really is part of my reality. But it's also for me, it is a way to say we're young and in love. We rent a house.

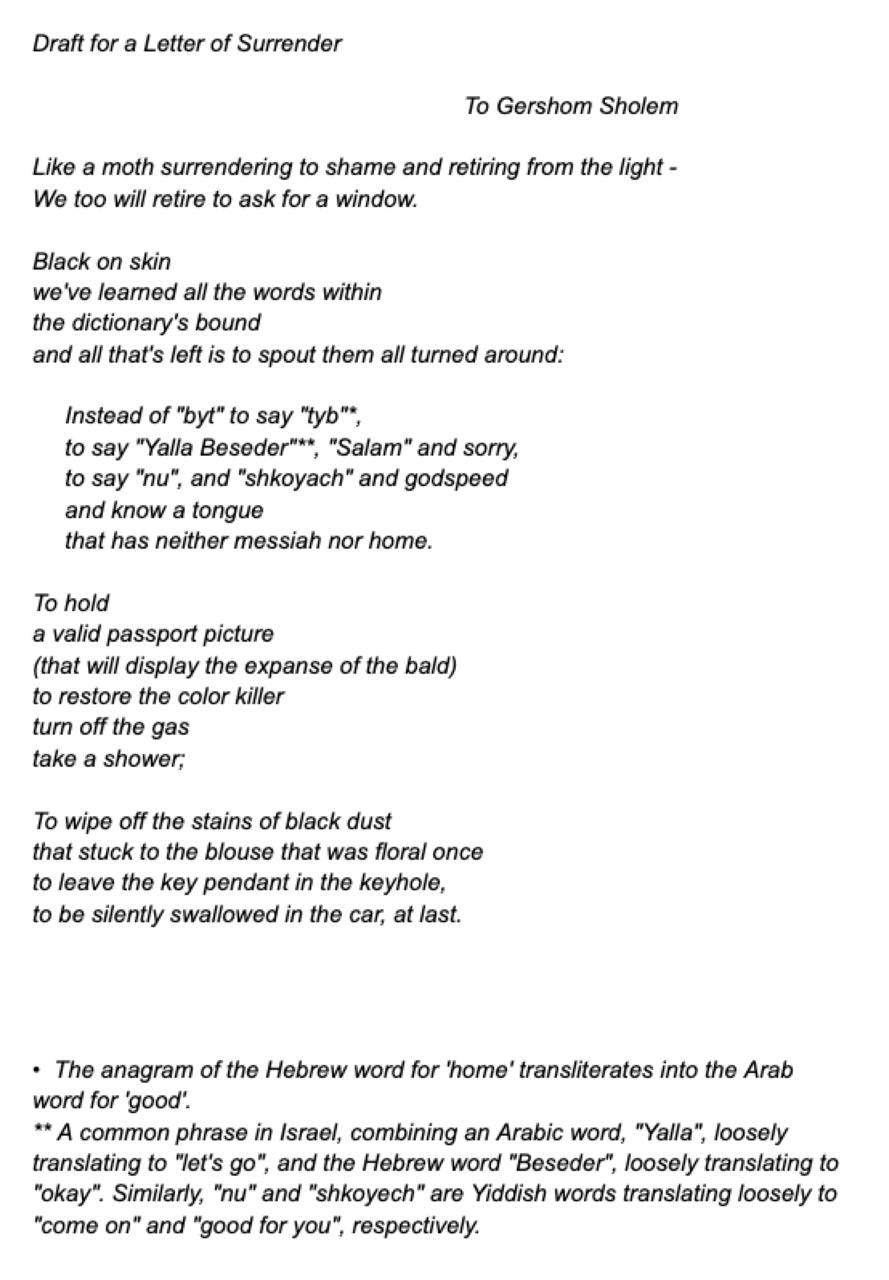

Right, because you can't buy it yet. All right, now we're going to come to really what I think is, of the three that we're going to do, the most overtly Israeli of the poems. Because this actually came out during the judicial reform protests, right? If I remember correctly.

Right.

So, I would just tell... I saw this form for the first time when you posted it on Facebook. Was it about a year ago-ish? Maybe, I don't know. Whatever. A little bit, whatever. And I forget what we were doing if it was a Shabbat or it was a holiday, whatever. But I always like to try to do something at the table that grounds the conversation in something serious without pulling out some ancient text so that my children and their spouses just roll their eyes and like, oh, God, here he goes again. So, I'm always trying to look for something that's a little bit different. And I saw your poem, and I wasn't even sure that I totally understood it. And it was just one thing, the anti-mechikon, which we'll get back to, that I didn't know what it was. And I actually asked my kids who didn't know, and they grew up here. They didn't know what it was, but my daughter-in-law knew what it was, or she thought she knew what it was, and you explained it to me more clearly.

But anyway, so we're going to read the poem, and I'll read it. This is a different translation that I worked on and your checking it with your person, so it'll be a joint project, but it'll be good enough. Probably not as great as his work, but it'll be good enough for our listeners to understand what it is that you're saying.

So, first of all, why is it to Gershom Shalom? It's dedicated to Gershom Shalom. Tell us two sentences about Gershom Shalom before you tell us why it's dedicated to him.

Gershom Shalom was the founder of mystical Jewish studies in the world.

He was an academic.

Academic.

He's the grand master of studies of Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah.

He was the first one, and for a while, the only one. In the Hebrew University. He really did a lot of things and write about a lot of things. But there is one, and he was really terrified and also very interested in messianism. There is this letter he wrote to Franz Rosenzweig. It became one of his most known texts, even though it was a small letter in his late years. And there he wrote that he was part of the movement of restoring the Hebrew and start talking in it again in Israel. But then he wrote in this letter that the this is very dangerous, that starting to speak in Hebrew, this Hebrew is so full with mystical and religious overtones, yeah like second word you say has its mystical meaning.

Right. Also, has it’s biblical meaning. It is on all levels. It's a very… The language is small but heavy.

Yeah, it is. He said, you speak, you're trying to make it a secular language, but it's not. And it will never be. What he said that this is very dangerous for Israel to speak in Hebrew because there is all this baggage to the language that will explode one day and will destroy this secular place we're trying to found. And I think for everybody who works with words, it's really interesting because we feel this this baggage of the language. We feel it. And also, for me, I grew up, I read the whole Bible five times. This is my language in really deep ways. I think it's really heavy being a writer in Israel with this kind of meanings to every word you write. You can't really run away from it.

So, why is this particular poem to Gershom Shalom?

Because this one is about what happens if us, the, I don't know, poets or the culture people will decide that it's too much and we leave.

It's too much. What's too much?

Being in Israel, writing in Hebrew.

And again, you wrote this during the judicial stuff when the country was in a very bad way.

Yeah. And it was in a very bad place. And also, it was in a place that we felt that the Hebrew is starting to explode, and that the meanings of being Jewish became racist and became dangerous. I called it in Hebrew tiyuta l’katav k’neia…

A draft of a letter of surrender.

Yeah. So, it's a draft. It's not a letter of surrender. But it is like I started to question myself is really, is writing in Hebrew and living in Hebrew is possible? And is it safe?

Okay, so let's just go through it. So, there's this moth, and the moth somehow leaves the fire, leaves the light, pulls itself away. It's also like the bird in the cage. And there's a lot of that here…. goes to seek a window.

Or a way out.

Or a way out, right. And then the rest of the poem is about a way out. But then there's this whole, you should say things backwards, right? Instead of saying bet, say tayeb, which is just the spelling out of the letter bet backwards... “lomar yallah, besder, salam u’slicha.” So yallah and besder because it's a combination of Hebrew and Arabic?

Yeah, and it became an Arabic term, an Arabic word. I think this part of the poem is really about maybe we should give the language to people who use it in different ways. It's like, instead of saying home, saying okay in Arabic, saying tov, tayeb. It's like the Haredi way of speaking.

Right, derech tzlecha is from the Tanakh…

Derech tzlecha is for us, like good luck and bon voyage. And then I suggest maybe we should know a language that has no messiah, but also no family.

Right, so no messianism, no messianic part, which is the Gershom Shalom piece, but also no family. I wonder if there are languages that don't have family.

For us, I have only one language, which is my family.

So, any other language be a language without family, I guess.

Yeah. For everyone who grew up in Hebrew. Yeah, I think it's really a suggestion, which is like, I think while writing it, I understand how impossible and terrible it is to give up my language and to give up my place.

But it's also terrible to feel that in some ways you want to.

Yeah. It's like, I want to say you won and just go away. But it is like, I have to give up so many things.

Okay. Now I'm interested in the list of things that you take when you get ready to leave. So “tmuna udkanit l’darkon,” it says to take an updated photograph for your passport, which will show the baldness.

The baldness.

Yeah. Then this “anti-mechikon machine” which you were the one to tell me what it was because I didn't know what it was. There was this, in Israel, in the 1950s, it's a crazy story, but Ben- Gurion was opposed to color television. He thought it would become like an opiate of the masses. If television went into color, people were going to watch too much TV…

It was also about equality. Some people didn't have a color TV, so everybody shouldn't have.

So, Israeli television, and there was only national television back then, they blocked the color. They took color things, and they showed them in black and white. And then, I didn't know this, but you'll explain to me in the 1950s so, of course, Israelis came up with a machine that you could attach to your television that would undo the blackout of the color and the anti- mechikon, which is the anti-erasure machine. So, it would restore it to color. I'm imagining not great color, but probably some color. And then you take that out. I don't know. You'll tell me in a minute why. If you're leaving, why do you need that machine? That's so Israeli. Just leave it here. But turn off the gas, take a shower.

Yeah, also, turn off the gas and take a shower. For Jews, it has something in the back of your mind. This is part of being a heavy language. You say things that are so mundane, and it's still have such a…

Although that would work in English, too. If you were a Jewish poet in America and you wrote, “turn off the gas and take a shower”, everybody with a Jewish historical sense would get that. But yes, it's built into the language. And why are we dusting off the shirt here towards the end?

It's a shirt that used to be floral and colorful. Then the whole situation here made it black and white. Now we are going away.

So, you're doing the same thing the anti- mechikon did…

Right.

I mean, you're restoring the color of the shirt the way the anti- mechikon restored the color to the TV. Then you leave the key ring or whatever it is.

So, this, too, is about there is a Palestinian symbol about the key on your neck. Carrying the keys. Yeah. I said, okay, we'll leave the key for you.

The first year we were here in 1998, We had friends who lived on Rehov Yehuda, which is right around the corner from us and very close to where we're sitting, who told me that there was one day, they were renting a house, an old Palestinian man knocked on the door with his grandson, and he showed them they key.

Was it the right key?

No, because the lock had been changed a thousand times. But he wanted to show his grandson their house, so to speak. They were very nervous for a minute, but he described the basic layout of the house, and it was clearly, he knew what he was talking about, so they let him in. And he whispered Arabic to his grandson, and they walked around the house, and then he left. Sort of a heartbreaking...

It is.

With this image of the key. And a lot of people point the Jews who left Poland and came here did not walk around with keys.

Yeah, they didn't have the time to take the key.

But also they didn't want to go back. That's true. I mean, in other words, the key is both a symbol of the Palestinian world saying, these are our houses, we want to come home. And our notion was also for us, going back is not going home. In other words, for us to come home was to leave there and come here, which is why it's so ironic, by the way, in these protests in America, now when you hear people saying to Israelis, go back where you came from.

Yeah, we don't want to go back.

Go back to the place that they tried to annihilate us or whatever. So, this is a very Israeli poem. There's nothing universal about this poem.

That's true.

It's very Israeli. It comes first on Gershom Shalom. And by the way, I mean, just like a key can have many references, and a shower and gas can have many references, Gershom Shalom has many references because he was also one of the founders of Brit Shalom, which is a movement early on, which is about Jewish and Arab coexistence and a dual, what do you call it? A shared state.

Yeah, they were against Ben-Gurion.

But he changed. And there's a book, there's an amazing book of letters between him and Hannah Arendt.

After the Eichmann trial.

Right. And it's hundreds of letters. And the book came out just a few years ago. And he has some amazing letters in there when he explains to her how he was disillusioned by the whole idea of a binational state or by coexistence. His argument was, they wanted to kill us in Europe. They want to kill us here. And so again, all you have to do in this society is say Gershom Shalom. So, you get mysticism and messianism and heaviness of language, but you also get the betrayal. If you want to talk about betrayal from the first poem, you get betrayal, he felt betrayed by the Arabs here who he was trying to hopefully build a coexistence with. So, it's all very heavy in it, whatever, which is why a person wants to say enough. I just…

Yeah, it's too heavy.

It's too heavy. I'm going to leave.

But I wrote it in Hebrew, in Israel.

But you wrote it in Hebrew, and you're sitting in Jerusalem having this conversation.

And it was published in Haaretz.

Would it have been published in Makor Rishon, you think?

That's a good question. I don't think Israelis know to read poetry that good. I think if it sounds good, they will publish it.

So, they wouldn't have necessarily understood the full impact of the problem.

Yeah, maybe. I don’t know.

I can only tell you that at our table, even though we didn't know what an anti- mechikon was, and I was really hoping that my very Israeli daughter-in-law would know, but she didn't really know. She's too young, I guess. And you knew about it from the Nathan Zach book, because he has a book with that name, which you told me. But I can tell you only that at our table, the conversation about this poem lasted a really long time. And it was actually just wonderful. We sat around. Some of us are immigrants. Some of us grew up here, but are technically immigrants. The in-law and kids are Israeli-Israeli. And it was your poem that enabled us to have a really meaningful conversation at a time when it was very hard to talk about things here. I mean, we're all politically more or less, I guess, in the same place. We're not one of those families that has to worry about, can we talk about politics at the table because it's going to explode? It's not going to explode. And we also just tiptoe away if it gets too complicated. But the poem really allowed us to talk about heaviness and past and present and stay, not stay.

It was an unbelievably beautiful poem. The minute I read it, and I just immediately printed it out right off your Facebook page, and we read it that night or the night after with our family. And all I can say is this. I mean, first of all, your work, it's always hard to talk about poetry in translation. Bialik had this line that, speaking of poets, he had this line that reading poetry in translation was like kissing the bride through the veil. I think he said it about any sacred text. I don't think it was only poetry. But kissing a bride through a veil, it's a kiss, but it's not the kiss that people dream of.

Yeah. And also, there is one of the way to explain what poetry is, is the things that is untranslatable.

Right. By definition, it's the things that are untranslatable, which is why you write in poetry, not in prose. But I think part of what our listeners are all interested in is trying to get a little bit of a sense of what's fascinating and interesting about Israeli society. And they're probably not puddling along during the day and saying, I wonder who the young Israeli poets are. But there are young Israeli poets.

There are many, and they're good.

Yeah. And so, this is our first conversation with one. Maybe we'll do more. But I think that your poetry, the three that we looked at today gives us a sense of both the universal, just very human dimension to your poetry, but also the very Israeli dimension, and the way in which even a seemingly universal poem has a little Israeli kvetch at the end. I can only rent a house, not buy a house.

We can't really separate the world that we live in from the universal things that we feel. So, I'll just end by thanking you again for your time.

Thank you.

And wishing you Mazal to open the appearance of your first book. I have no doubt that by the time you're my age, there's going to be a bookshelf of books by Noa Sorek. And I hope that our listeners will follow you and that maybe one day somebody will put out your poetry in a formal English collection of translation. That would be great. It's hard to do, but it would be great. But for telling us a little bit about this side of Israeli society, young people becoming poets and giving us a chance to feel it, smell it, taste it, hear it. Just thank you very much, and good luck with the book.

Thank you so much.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

"Maybe Copernicus never knew what love is"