Before getting to today’s topic below, a quick word about this Wednesday’s podcast on the subject of Iran, with Colonel Dr. Eran Lerman.

With a new “Iran deal” in the works (though whether it will come to be is impossible to say), we turned for this week’s podcast to my colleague at Shalem College, Colonel Dr. Eran Lerman, to ask a basic question that most of us can’t answer: “Why does Iran hate Israel with such intensity?” It’s not borders—we don’t share one. It’s not oil. It’s not water. It’s not being a Muslim country—look at the UAE, Bahrain and others.

So what is it? Why is Iran so committed to Israel’s destruction?

No one is better positioned to explain that than Dr. Lerman. Eran Lerman was deputy director for foreign policy and international affairs at the National Security Council in the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office, prior to which he held senior posts in IDF Military Intelligence for over 20 years.

The link above will take you to a brief excerpt of our conversation (after the section in which he explains the origins of Iran’s hatred for Israel), in which Dr. Lerman speaks about what is at stake for Israel if the deal goes through. We’ll post our full conversation with Dr. Lerman, along with a transcript for those who prefer to read, this Wednesday, as usual. The conversation will be available to paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

If I had a sermon ….

It’s the beginning of the month of Elul, the last month of the year, the month that immediately precedes Rosh Hashanah. For the next several weeks in our neighborhood, like in countless other neighborhoods across Israel, if you sleep with the windows open, the first thing you’re likely to hear in the morning is the sound of the shofar from one of the countless minyanim within a hundred yards. Most of the year, you don’t even know they’re there. The entrances are on little alleyways, off the main streets, and unless you’re outside at the crack of dawn, you’d have no occasion to see people scurrying to and from these little synagogues day in and day out.

But this month you hear them. You hear the one you go to, if you go, and you hear the many others that you don’t attend. It’s as if the new year is in the air.

If you were a rabbi of a congregation in the US, you’d be stressing now. Because there is a ton to do, and because if your sermons are not written, you know that you need to get cracking. And if they are done, you’d be second-guessing yourself as to whether you’d chosen the right topics.

To add to the complexity, you’d have, among other decisions to make, a difficult decision about Israel. Should I speak about Israel? Can it be done without creating divisiveness? Many rabbis think not. In fact, Israel’s a topic that many rabbis say they avoid speaking about from the pulpit.

Chatting with a pulpit-rabbi-friend last week about this precise challenge, I found myself asking what I would say if I had to give a sermon about Israel on Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur. What could I say that that would not be divisive? What would be the most important thing to say about the Jewish state?

This year in particular, the year that Israel will turn 75, I think that I would speak about purpose and about love. I’d want to get people to ask themselves why Israel was created in the first place and what kind of a place a country has to be for us to love it.

Let’s start with the end, with love. Love is hard—that’s the bottom line. Love is hard with a spouse or a partner, and it’s hard with kids. It’s hard with parents, often as they get older and are less and less like the people who raised us and shaped us. Love is hard with our closest friends.

Love is just hard. That’s what’s so problematic with that Disney-esque notion of “and they lived happily ever after.” No one lives happily ever after. True, I understand that ending a kids’ movie with “they had their ups and their downs, but they worked at it constantly, and in the end, they kept relearning how to love each other and made it work” isn’t exactly what keeps a kid staring breathlessly at the screen.

But marketing aside, it would be more honest.

It's the best we can aspire to.

Loving a country is no different. Americans who love America now, no matter what side of the aisle they may occupy, love a country that is not only highly problematic, but that shows worrying signs of coming apart at the seams. But I don’t hear my family or my friends or my acquaintances saying that they’re giving up on America. That because it can’t solve its race problem, they’re done with it. Because the human disaster unfolding at the southern border is beyond repair, they’re done. Because facts and truth no longer count for anything, they’re done. Because America is so deeply divided between competing visions of what the country should be with no fix anywhere in sight, they’re done.

Because when it comes to America, the people I know are heartbroken (and increasingly, frightened), but they’re not done. They’re in for the long haul. Because that’s what loyalty demands. That’s what love is.

And then I might say something about perfection, and the notion that in many ways, Judaism abhors it. OK, “abhor” may be too strong, but it’s not entirely wrong. We are a people that does not demand perfection. It’s something to strive for, not something to achieve. And in our world, something’s or someone’s not being perfect is no reason to jettison it or them.

The Book of Genesis describes Abimelech’s reproaching Abraham after Abraham had passed off Sarai as his sister, rather than as his wife:

Then Abimelech summoned Abraham and said to him, “What have you done to us? What wrong have I done that you should bring so great a guilt upon me and my kingdom? You have done to me things that ought not to be done.”

Abimelech is right. Abraham had “done things that ought not to be done,” things that could have had disastrous consequences. And the consequence for Abraham in our tradition? He’s a forefather. He’s all over the liturgy. We invoke his righteousness as we plead for God’s favor.

Or how about King David and Batsheva? True, there are rabbinic texts that insist that he didn’t do anything wrong, but the biblical text is pretty clear. David slept with Batsheva, got her pregnant, and then, to cover his tracks, essentially had Batsheva’s innocent husband killed. And the consequence for King David in our tradition? The Messiah, it is said, will come from his stock.

The examples are virtually endless. On the one hand, at our best, we strive for perfection. But on the other, our tradition doesn’t expect it of us, or of forefathers, or of the stock of the Messiah.

Perhaps that is why Israel has not fallen prey to the wave of institutions being renamed and statues being torn down that we see elsewhere. In fact, it hasn’t happened here at all. David Ben-Gurion, for example, was far from perfect. To take but one issue, he said some very nasty things about (and did some pretty horrible things to) Jews of darker color. It was—and is—immoral and shameful. Yet do you see anyone at all calling for renaming Ben-Gurion University? The airport? Anything else?

Ben-Gurion was, like the country he did much to create, highly imperfect, terribly flawed … and extraordinary, all at the same time.

It’s hard to love imperfection. But if someone loves us, they’re in love with imperfection. It’s hard, but that’s all there is. That’s what makes love the great gift that it is.

Which leads us to Israel. An imperfect country, a country that can be hard to love.

Which, in turn, leads us to purpose.

Why does this country exist? Why did the Jewish people get into the state-making business? The Jews embraced Zionism—the national liberation movement of the Jewish people—in order to transform the existential condition of the Jewish people. Has it succeeded? It’s succeeded so wildly that it’s hard for us to remember how different a people we were not all that long ago.

For millennia, it had seemed that the Babylonian Exile had irrevocably transformed the Jewish people into a Diaspora people, with only a small minority of Jews living in their ancestral homeland. By Israel’s 100th anniversary in 2048, though, demographers predict, two-thirds of the world’s Jews will live in the Jewish State. It will be Diaspora communities that will constitute the small minority. That, Zionism turned on its head.

Zionism sought to change not only demographics, but the Jew herself. Zionism was about, as we know, the fashioning of a “new Jew.” Leon Pinsker mourned the loss of a Jewish language, so Eliezer Ben-Yehuda acted, devoting his life to reviving ancient Hebrew and transforming it into a modern language. Today, millions of Israelis speak the language of the Bible; they take it so for granted that they do not realize that an Israeli bookstore, with hundreds of linear feet of shelves of books written in a language that not long ago virtually no one spoke, is miraculous.

Max Nordau lamented the fact that “we have been engaged in the mortification of our own flesh. Or rather, to put it more precisely—others did the killing of our flesh for us.” Zionism brought an end to that, as well. The Jews’ acquisition of power was never going to be simple, and tragically, bringing an end to Jewish victimhood has come with great costs, in life, limb, capital, and endless moral complexity. But power has done what it was meant to do—Jews are no longer victims on call.

In 1891, a nineteen-year-old Bialik published his first poem, “To the Bird,” in which the narrator, heartbroken at what was happening in Europe, asked a bird just returning from the warm climes of Palestine, “In that warm and beautiful land, does evil reign and do calamities happen, too?” Or perhaps, Bialik allows himself to wonder, “Does God have mercy on Zion?”

Israel was meant to end heartbreak as the predominant characteristic of Jewish life. Israel still experiences its share of horrors, and to be sure, calamities still happen. But evil does not reign. Were he alive today, if he compared Jewish life in Israel to the life that he knew growing up in Eastern Europe, Bialik would say: “God does, indeed, have mercy on Zion.” Life is far from perfect, and tears flow aplenty. Still, life is not merely better—it is infinitely better.

The vibrancy of Jewish life in Israel as anyone who has been here know it exists because Israelis no longer live in existential fear, and because Israel has eradicated heartbreak as the foundational characteristic of Jewish life. That is why Israel ranks so high on the World Happiness Scale (way higher than the US) and has a higher birthrate even among secular Jewish women than any other OECD country. This, despite the high stress, compulsory military service, regular armed conflagrations, unremitting international opprobrium, and challenges aplenty.

It is because now the Jews feel safe—and no less important, because statehood has given Israelis a sense of purpose.

There are many dimensions to that sense of purpose; but no matter how Israelis articulate it to themselves, a central tenet of that purpose has to do with renewing their people, and in the process, having become actors in one of the greatest stories of human rebirth in all of history.

It is, as I said in the title of a book decades ago, a “place that can make you cry.” It can make you cry with rage at things that “ought not be done” and frustration at opportunities missed. But it can also make you cry with wonder … at how in a mere 75 years, a tiny place like this has utterly transformed the destiny of a people that’s been around for four thousand years.

Is this place even close to perfect? No, it is not.

Is it easy to love this place? No, it is not.

But love it we must, I would say if I had to speak about Israel.

Because we need it, and because its extraordinary accomplishments merit it.

“Love something so deeply flawed?”, some might ask in response.

Yes, I would say, because everything we love is imperfect. Our challenge is to give that gift of love generously—to family, to friends and to our nation.

Because nothing more is possible.

And because nothing less could be called loyalty to our people.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

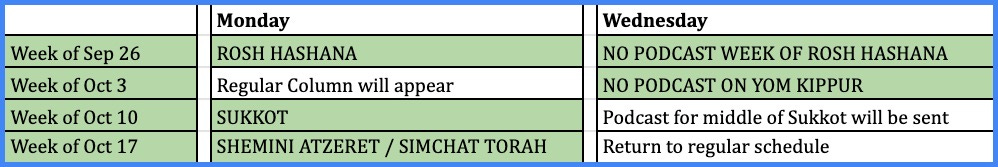

With the holidays coming up and many of them falling on Mondays (our column day) and Yom Kippur on Wednesday (podcast day), here is the tentative schedule for Israel from the Inside for the weeks of the holidays:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

"If I had a sermon ...."