"Modern Israel is the Jewish people's very last chance."

Charles Krauthammer was right: "Israel is the hinge. Upon it rest the hopes—the only hope—for Jewish continuity and survival." Everywhere.

WRITTEN COLUMN FOLLOWS BELOW

On April 19th, I’ll be in dialogue with Abigail Pogrebin at Temple Emanuel’s Streicker Cultural Center, speaking about my book, Impossible Takes Longer, that will have come out the week before. Information and registration on the Streicker Center website, here.

I was sitting in shul last Friday night, the room (a gymnasium in a community center) packed to the gills as it always is. It’s a young crowd, mostly parents of little children, and an accomplished one. A huge portion of the people there are academics, lawyers, doctors, hi-tech people (it’s not unusual to hear people asking each other how their week was and to hear someone say that they just got back from ringing the opening bell on the NYSE). It’s what one would call an “Orthodox egalitarian” synagogue – there’s a mechitzah, with men and women sitting separately, but men and women have equal roles. Welcome to Baka, one of those neighborhoods that has become a laboratory of religious creativity – among people who actually know what they’re doing. Virtually everyone in the congregation is observant, virtually all the men and many of the women have been to yeshivot or seminaries for many years, the vast majority continue to study intensively and regularly. It’s a pretty serious crowd.

Serious, yes, but also spirited. And on Friday night, as my mind wandered and I found myself glancing at the various books people had brought with them to read while they were there, and I was then brought back into focus by the singing that literally had the room vibrating, I had two thoughts:

This is (one of the many different sorts of moments of) the very best that Israel is and can be.

This may not last. The young kids in the room, who will presumably be no less educated and talented than their parents, will not stay in a country that has become an illiberal democracy. They will not stay in a country in which intolerant views of women, Arabs, non-Orthodox Jews, academic openness, intellectual creativity all feel like they are on the defensive. They may be legally protected, or they may not – that still remains to be seen. But in a society that feels at its core illiberal, the little kids running around that gymnasium are likely to make their adult lives elsewhere.

That has become the topic of conversation at almost everyone’s Shabbat tables. “Who’s going to stay?” Every meal, every conversation, every Saturday night hanging out at the protests … someone within earshot asks that.

On a recent Shabbat evening, one couple at our table had a conversation between the two of them, aloud. She said, “A few years ago, if our children had decided to leave Israel, I would have felt betrayed. Now, I wouldn’t. I’d understand them.” To which he replied, “I still wouldn’t want them to leave … I want Jewish great-grandchildren.”

I couldn’t help but notice that his argument (suffice it to say that he is brilliant, an extremely successful, widely known Israeli professional) wasn’t that Jewish life here was richer, or more meaningful, or more likely to shape the future of the Jewish people. His point was purely demographic. So far, at least, if his (already born) grandchildren raise their eventual children in Israel, there will be a higher probability that they’ll marry Jews.

That’s a demographic argument—hardly the full-throated endorsement of the wondrous life of Israel that one would have heard around the Shabbat table a year ago.

The corollary conversation one hears constantly (at least among our generation, though I hear from my kids that it’s bubbling in theirs, too) is “where would you go?” It doesn’t really matter what each person says. Our kids’ generation seems to mention Italy or Germany a lot. I’m not sure why, though the ironies of those possibilities are too rich to summarize here.

Among our generation, the presumption seems to be that if people had to leave, they’d “go back,” ie to the America that most of us left.

These conversations are all sufficiently sober that it feels to me each time that there’s no point in noting the obvious, which many people around these Shabbat tables and coffee tables and porch tables don’t want to acknowledge. But in this context, it’s worth noting:

If Israel becomes a country in which many of us do not want to live (I cannot imagine leaving, but that’s another, irrelevant story at the moment), then American Judaism is over. If Israel as a liberal democracy fades (or collapses, though fading seems more likely), it’s all over for American Judaism, too.

Why would American Jewish life be over if liberal-democratic-culturally-flourishing Israeli life were over? It’s because even a controversial Israel provided energy for Jewish life that no other issue can, anymore. It’s because when American Jews disagreed with Israel’s policies or were horrified by its actions, they were moved by the rebirth of the Jewish people in its ancestral homeland, they were still mesmerized by Israel, whether they wanted to admit it or not.

Israel mesmerizes the world—and even the vast majority of American Jews— because it is an almost magical story. A people that had been defeated 2,000 years earlier and had spent millennia dispersed without political power somehow managed to survive while the ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks, Romans, and others who defeated it are now gone. Of all the peoples of the ancient Western world, the Jews are the only ones who managed to survive for century upon century. As the historian Barbara Tuchman has noted, it is only the Jews who speak the same language, practice the same religion, and live in the same land as they did in ancient times.1

When the Third Reich devised the “Final Solution to the Jewish Problem,” almost all the world either conspired or looked the other way, and the Jews came perilously close to the end. Yet just three years after the war, what just decades earlier had been a tiny enclave of Jews in Palestine had now become sufficiently populous and powerful to declare independence. One of the world’s oldest peoples had created one of the world’s newest countries. Jews, long synonymous with the image of “victims on call,” had taken up arms and taken their destiny back into their own hands.

Israel mesmerizes because it is one of the greatest stories of resilience, of rebirth, and of triumph in human history. Israel fascinates because it is without question the most astoundingly successful example of a national liberation movement. Yes, though we rarely speak about it that way, that is what Zionism is: it is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people everywhere, and that intuition has fueled American Jewish life no less than it has Israeli life.

That is why even American Jews who cannot abide the policies or attitudes of the Jewish state embrace the opportunity to meet the people who live there.2

At summer camps or on university campuses, where Israelis are engaged as staff, thousands of young American Jews have found their encounters with those Israelis the most compelling experience in their Jewish educations. The Israelis, who come from such a different world and live with such different expectations of what life can provide and what they have to give in return, spark a process in these young American Jews that nothing else has previously elicited. The “magic” of all these encounters with Israelis stems from American Jews being exposed to a version of Jewish life wholly unlike their own lives in the United States. To put matters a bit differently, when it comes to the drama of the Jewish people, there actually is, despite many American Jews’ reasoned objections to the notion, a new center of the Jewish world.

As Charles Krauthammer, not only a uniquely articulate political observer but also a committed American Jew, once noted:

The return to Zion is now the principal drama of Jewish history. What began as an experiment has become the very heart of the Jewish people—its cultural, spiritual, and psychological center, soon to become its demographic center as well. Israel is the hinge. Upon it rest the hopes—the only hope—for Jewish continuity and survival.

Part of the drama emerges from a sense—even among American Jews—that what is at stake in Israel is not merely the Jewish state, but the future of the Jewish people, the people whom the state was created to save. That is why Krauthammer began by speaking about drama but two sentences later claims that Israel is “the only hope” for Jewish survival. Lest his readers miss his point, he spells it out:3

It is my contention that on Israel—on its existence and survival—hangs the very existence and survival of the Jewish people. Or, to put the thesis in the negative, that the end of Israel means the end of the Jewish people. They survived destruction and exile at the hands of Babylon in 586 B.C. They survived destruction and exile at the hands of Rome in 70 A.D., and finally in 132 A.D. They cannot survive another destruction and exile. The Third Commonwealth—modern Israel, born just 50 years ago—is the last.

Jonathan Safran Foer suggests much the same thing in Here I Am, his powerful novel about Israel in a time of crisis, in the voice of Israel’s prime minister. With Israel in peril, the prime minister calls on American Jews to stand at Israel’s side—not out of pity for Israelis, but because they, too, are at stake. “As the prime minister of the State of Israel,” Israel’s leader says on live television,

“I am here to tell you tonight that if we fall down again, the book of Lamentations will not only be given a new chapter, it will be given an end. The story of the Jewish people—our story—will be told alongside the stories of the Vikings and Mayans.”

Israel as “the principal drama of Jewish history”: the notion was understandably troubling to American Jews decades ago, but at this point it is hard to deny. The idea that a flourishing Jewish community can proceed without Israel as a core part of its identity is simply not realistic. Communities need passion and drama to survive, to fuel the conversations that animate their lives. And if a community needs drama, Krauthammer and Foer—like Philip Roth much earlier in Portnoy’s Complaint (for a different column)—cannot imagine it coming from anywhere but Israel.

Here is the great irony about discussions of Israel among American Jews. Though many American Jews are (often understandably) deeply frustrated with or even embarrassed by Israel, Israel remains the only subject of Jewish substance that has the capacity to arouse passionate debate across the entire American Jewish political and religious spectrum. Whereas decades ago American Jews were anguished about “Jewish continuity,” that subject has virtually disappeared from today’s discourse. “Who is a Jew” or “who is a rabbi,” issues that were formerly explosive in American Jewish life, have vanished from the communal agenda.

Which theological issues still arouse the explosive and divisive debates that Israel does? Conversations about whether democracy is even a Jewish value? Whether Judaism traditionally favors a free market economy or one with guaranteed equality?

The LGBTQ community and gay marriage, or standards for conversion, were once lightning-rod issues in the American Jewish community. Today all that debate, too, seems to have ended. Now each sub-community does what it does, while the others cannot be bothered to care very much.

Only when it comes to Israel do the statements and actions of one denomination or segment of the political spectrum immediately arouse passionate reaction from others.

There is a reason for that.

The sad reality is that the wealthiest and most politically involved, culturally invested, and secularly educated Diaspora community in the entire history of the Jewish people is also, by far, the least Jewishly literate community ever created by Jewish people. As a result, too many American Jews, absent Israel, simply do not know enough to have a passionate conversation about almost any other dimension of Judaism. What that means is this: take Israel out of the equation and there will likely be almost nothing left that can arouse the passions of the American Jewish community. But a community devoid of passion is not one that people will find reason to care about.

It may not matter that American Judaism will fade in terms of people’s choices. The sadness of what we’ve lost in Israel—should that happen, which I still pray it will not—will be too great for it to matter very much where we live.

While I fear (with a high degree of confidence) that no meaningful version of American Jewish life would survive Israel’s self-destruction, it’s worth noting that mine is far from the most extreme framing of the issue. Hillel Halkin (who happens to be my cousin), wrote in his most recent book that he hoped that American Judaism would not survive if Israel did not make it:4

A few years ago, I participated in a panel discussion about Israel and the Diaspora held in Washington, D.C. As I generally do on such occasions, I spoke my mind. When the time came for questions from the audience, a man rose and asked me:

“Even if you’re right about the inconsequentiality of Jewish life in the Diaspora compared with that in Israel, suppose, God forbid, that Israel should destroyed by a nuclear attack. Wouldn’t you be glad then that American Jewry existed, so that it wouldn’t be the end of the Jewish people?”

“To tell you the truth,” I answered spontaneously, “if Israel were destroyed, I hope it would be the end of the Jewish people.”

There was a shocked silence before another questioner was called on. When the evening was over, a fellow panelist turned to me and said, “I hope you didn’t mean that.”

I thought for a moment.

“Yes,” I said. “I did.” If Israel should ever go under, I would not want there to be any more Jews in the world.

What for?

Things haven’t been this good for the world’s Jews in two thousand years. In one respect only are they worse. During that period we were a people that had lost a first temple and a second; yet as great as our misfortunes were, we did not have a third temple to lose. Today, we do. If we cannot safeguard it, it would be as shameless as it would be pointless to want to go on. In Jewish history, too, three strikes and you’re out.

At a certain point, it makes no difference if you buy Halkin’s take, or mine (or neither). Let’s just not delude ourselves. What we’re watching unfold in Israel is the future of all of us. If an Israel of which we cannot be proud does not survive, it’s over for the Jews as we know them

—no matter where they may be.

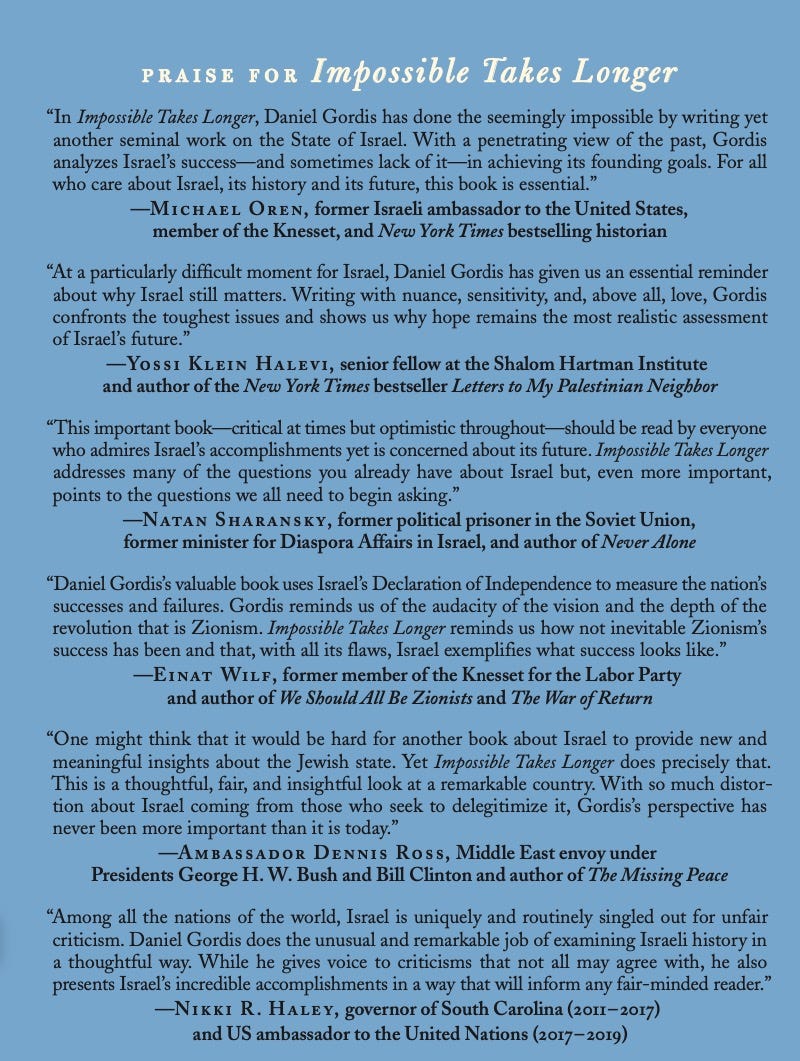

Impossible Takes Longer will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Barbara Tuchman: Practicing History (New York, 1981). Her comment is in the essay “Israel: Land of Unlimited Impossibilities,” 134.

Much of the following section is based on a section of my book We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel.

Charles Krauthammer, “At last, Zion” https://tikvahfund.org/library/transcript-charles-krauthammer-at-last-zion/.

Hillel Halkin, A Complicated Jew, Kindle Location 3290.

The American Jewish community is an outlier in terms of its low observance and generally secular values. The British Jewish community is ~25% Orthodox. That share rises to almost half of all young children.

Besides, I think the Haredi sects in Brooklyn will continue without much of a problem. Overtime, they will bleed converts to more secular streams like happened in previous centuries.

What you're describing isn't an "end to the people" so much as an end to a hyper-secular subgroup whose sole religion seem to be Zionism. The Bret Stephens types.

P.S. it would be interesting to know what the Mizrahi Jewish population in Israel thinks. Not only do they support the government in much greater numbers than the Ashkenazim, many of them are quite rooted now. The last major wave came well over half a century ago.

Moreover, their family history before the creation of Israel isn't in the West, which is an additional barrier. I suspect the appetite for emigration among them is significantly lower, even if these reforms were to pass eventually.

Sorry, Mr. Gordis, but it seems that many members of your "Orthodox Egalitarian" congregation (filled with all those oh-so-cultured and educated professionals you admire so much)are no less arrogant than the rest of the part of the country with leftist inclinations, who have decided for the majority of us (yes, the majority, who voted in the present government, and the 58% of the Jewish population who voted for said government-and I mention that statistic since we are patronized by people who claim they want an Israel Jewish and democratic, but themselves intolerant of much of anything that smacks of Judaism). The "illiberal democracy" you so decry has been with us for a long time, exacerbated in the extreme by the exercise of unwarranted and unlimited power of the judicial and legal elite, a power not even seen in the USA, where (for just one example) supreme court justices are nominated and chosen by representatives of the people, and not by the judges themselves or some self-important lawyers from a national legal fraternity!) My pride in Israel (and I am here 42 years) is not diminished by a government I did not vote for, or even abysmal and insane utterances of various politicians (of whatever stripe). I am also not overly impressed with those who think that because of their position and their place, that dragging Israel through the mud, and even endangering it, is "fine and dandy"! As is said, arrogance knows no bounds. This is what we have here in Israel, not a "war of brothers" or "divisiveness" (which always was and always will be with us), but a group of people who just cannot fathom having the country's institutions representing all its citizens, and whose screams of "de-mo-cra-tia" ring hollow and self-serving!