The image above, which says שישה באב “Shisha B’Av,” or “The Sixth of Av,” went viral a year ago on Israeli social media, just three days before the Ninth of Av. That was the day that the Knesset, despite overwhelming public objection, passed the first of the changes to Israel’s judicial system—a plank called the “reasonability clause.” Many of us, myself included, had been certain that the Knesset would balk at the last moment. With the country coming apart at the seams, they’d step back from the abyss.

But then we learned. Yariv Levin and Simcha Rothman, who were leading the judicial reform charge, were zealots. They would stop at nothing. They would bring the house down. Hence the “Sixth of Av” meme.

Today, after ten months of war, it’s hard to remember what this country was like two months before October 7th. Now, after ten months of war, one can be temped to feel that “those were the good old days, when all we were worried about was the Supreme Court.”

But to fully understand one of the Talmud’s stories about the Fall of Jerusalem (one of the few texts we’re permitted to study on Tisha B’Av), we need to remember that that’s not all we were worried about. Even then, many of us, on both sides of the judicial reform divide, were already worried that the whole project was falling apart.

So we begin the Talmud’s story about everything coming apart and the downfall of Jerusalem (which is actually very, very long and extends over several Talmudic pages) with zealots. Not those zealots of last year, but those of two thousand years ago.

There were certain zealots among the people of Jerusalem. The Sages said to them: Let us go out and make peace with the Romans. But the zealots did not allow them to do this. The zealots said to the Sages: Let us go out and engage in battle against the Romans. But the Sages said to them: You will not be successful. It would be better for you to wait until the siege is broken. In order to force the residents of the city to engage in battle, the zealots arose and burned down these storehouses [ambarei] of wheat and barley, and there was a general famine.

The zealots, desperate for battle, decided to burn down the Jews’ own storehouses to bring the crisis on. That’s precisely what had happened on the Sixth of Av last year. This year, too, we’re hardly short of zealots.

Someone suggested to me a few days ago that for Tisha B’Av this year—i.e., today—we should re-post what we’d posted last year for Tisha B’Av. What we’d posted was a conversation that I had with Rabbi Marc Baker, of Boston’s Combined Jewish Philanthropies on Tisha B’Av afternoon. (The post, “The Ghost of Destruction Still Haunted the Land,” contains the full recording and is accessible to all.)

I hadn’t watched that recording in a year, and had no recollection of what was in it. But when I reviewed it, I was struck by the fact that—though things are much worse now—even then, we were broken. Even then, in a horrible summer in which no one could have imagined the horrors of October 7th, we were already wondering whether this project called the State of Israel was winding down, being pulled apart by the very people who were supposed to be leading it.

That was why, in the opening clip above, I found myself sharing with Rabbi Baker how people had sat on the ground to read Lamentations, and simply burst into tears. Three days after a vote in the Knesset many of us had been certain would not ultimately happen, the only response that made any sense was to weep.

Last night, in the same spot, many of the same people gathered to read Lamentations once again. This time, we knew going in that it was going to be unbearable. There are 115 people, alive and dead, that this once powerful nation simply cannot retrieve. There are 115 families living an indescribable hell. Our sons and daughters are at war. Our grandchildren are petrified when their fathers leave. And for the second time in four months last night, the entire country held its breath waiting to see if we were going to be attacked by Iran.

Was this what we had in mind when we sang להיות עם חופשי בארצנו, “to be a free people in our land”?

What have we learned this year? Many things. Including what it means to be much, much less powerful than we’d thought. What it means, at moments, even to be weak. What it means, like in the Talmudic story above, to have inflicted many of these wounds on ourselves.

So, yes. Last night people wept again. This time, it was not in the least bit surprising.

The Talmud’s story continues after the zealots burn the storehouses:

With regard to this famine it is related that Marta bat Baitos was one of the wealthy women of Jerusalem. She sent out her agent and said to him: Go bring me fine flour [semida]. By the time he went, the fine flour was already sold. He came and said to her: There is no fine flour, but there is ordinary flour. She said to him: Go then and bring me ordinary flour. By the time he went, the ordinary flour was also sold. He came and said to her: There is no ordinary flour, but there is coarse flour [gushkera]. She said to him: Go then and bring me coarse flour. By the time he went, the coarse flour was already sold. He came and said to her: There is no coarse flour, but there is barley flour. She said to him: Go then and bring me barley flour. But once again, by the time he went, the barley flour was also sold. She had just removed her shoes, but she said: I will go out myself and see if I can find something to eat. She stepped on some dung, which stuck to her foot, and, overcome by disgust, she died.

People don’t die from stepping in dung, and they don’t die from being disgusted. So for many years, I’ve thought that the last part of the this section was not as powerful as the rest. I was wrong—I think that now I understand why Marta Bat Baitos died. We’ll come back to that.

Prior to that, though, that the story of the search for flour—first fine flour, then ordinary flour, then coarse flour, then barley flour—is about is the story of an economy slowly collapsing because a people has turned on itself.

Can one read yesterday’s headline about Fitch downgrading Israel’s credit because of “political fractiousness and coalition politics” and not hear the echoes of this story? Have we learned nothing?

Even last summer, we understood how deeply wounded we were, and we were, as I noted in this clip just below, “scared out of our minds.” We knew that the first Jewish commonwealth had lasted 73 years, the second had lasted 74 years, and last summer, we were in year 75.

Last summer, a quarter of Israelis said that they wanted to leave. Thousands of doctors were looking at relocating. We knew that the army was a mess, largely as a result of our own doing.

What we didn’t understand last summer was that our enemies saw our weakness, too. What we didn’t understand was that on this Tisha B’Av, we’d be feeling our weakness even more deeply.

So why did Marta Bat Baitos die? From dung? From disgust?

She died, I think, because her heart broke. Because as the enormity of the crisis gradually sunk in, as there was less and less to eat (and presumably, less and less of everything, from goods to good will to hope) she had less and less to hold on to. So that when she finally stepped in dung, her heart just gave out.

Because her heart had known long before that it was over.

Still, the rabbis apparently had trouble with this idea that mere disgust could have killed her, so in the continuation of the story, they suggested that it wasn’t stepping in dung that did her in, but instead, her eating a fig of Rabbi Tzadok.

There are those who say that she did not step on dung, but rather she ate a fig of Rabbi Tzadok, and became disgusted and died. What are these figs? Rabbi Tzadok observed fasts for forty years, praying that Jerusalem would not be destroyed. He became so emaciated from fasting that when he would eat something it was visible from the outside of his body.

Who was this Rabbi Tzadok? All we need to know about him at this moment is that he’d seen it coming. He’d observed fasts for forty years—a very, very long time—praying that Jerusalem would not be destroyed. But he knew. He prayed and fasted, but no one listened. No one learned anything. No one changed anything. And when Marta Bat Baitos ate one of the figs that he had presumably already sucked dry, she died.

In the end, though, it’s the same cause of death. Eating what he’d eaten, she saw the world his way. She saw that we should have seen it coming. She saw that we could have prevented it, but we didn’t.

So she did the only thing that made sense. She died.

What about us? Are we willing to acknowledge how deep is the crisis, not only externally but internally as well? Did we understand last year? Do we understand better this year?

If last year, the meme of the moment was the “Sixth of Av,” this year, it became not the Sixth, but the Seventh. שבעה באוקטובר. And not Av, but October. The “Seventh of October,” obviously, but also because the word for “seventh”, shiva, is also, well, שבעה or “shiva.”

The “seventh of October”, or “mourning in October.” Either way, the similarity between last year’s meme and this year’s is impossible to miss.

It’s taken on all forms. Some people have added a “broken heart” emoji. Others have put it on cell phone cases

But whether it’s the font or the emoji, every rendering conveys brokenness. Because that is where we are—where we are supposed to be today, on Tisha B’Av, but where we will be when this day ends, too.

At this moment, there is not much we can do to determine whether we’ll be attacked today, tonight, laster this week, or beyond (though the possibility of pre-emption is apparently on the table).

We can hope that we won’t be. We can hope that if we are attacked, then we’ll be able to protect ourselves. We can hope that if we use the attack as the moment to push Hezbollah away from the border so residents of the north can return home, that our casualties will be as few as possible.

We can hope a lot of things.

But first, we could also do.

We could remind ourselves that the whole point of Tisha B’Av is to insist that once we forsake each other, it’s over. If we go to war and have not gotten the hostages back, many analysts say, it will be too late. Whether or not this country could survive under the weight of the moral blemish that it didn’t save those lives when it could is a very open question.

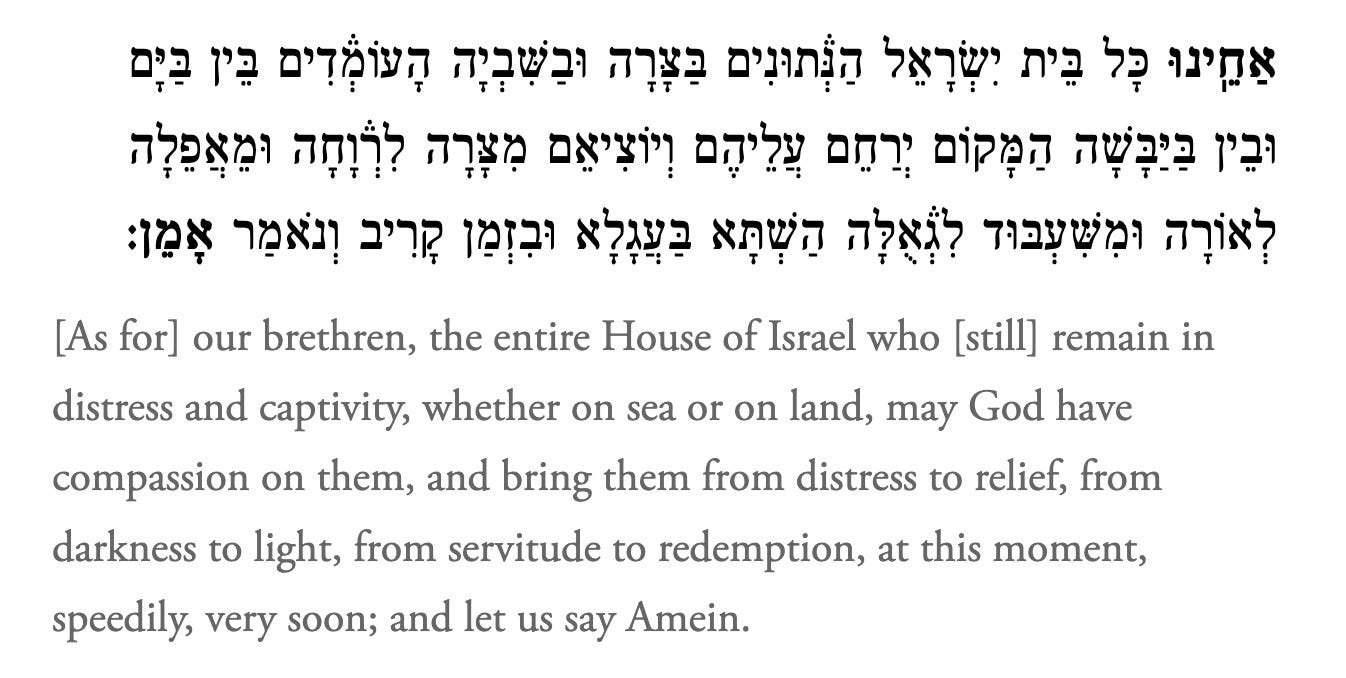

So, not surprisingly, after we read Lamentations last night, we sang “Acheinu” (the traditional prayer for hostages, see below for words and a recording). Last year, some of the people wept. This year, there wasn’t a dry eye.

Last year, we’d inflicted the wound on ourselves, and on Tisha B’Av, had no idea how much worse things were about to get. This year, some of the wound we inflicted, some was inflicted on us. And once again, we have no idea what we are about to face.

But we could, at least, do the right thing, and difficult thought the deal will be, not let dozens of children, women and men languish in the horror of Hamas darkness. Maybe, just maybe, if we found the courage to do the right thing once, we’d find that we could do the right thing again. And then again. And then, perhaps, we might begin to heal? To save this place?

That was why the only way to end last night was with the prayer for the hostages. Because what we do about them will say everything about what kind of a society we are—or aren’t.

So in the waning hours of Tisha B’av here in Israel, we end this post with that prayer, once again:

Tisha B'Av one year ago: the good old days were already not so good; even last year, people were already weeping over what had happened to our country