Many of the columns and podcast episodes in Israel from the Inside have touched on the notion of the “new Jew,” Zionism’s drive not only to create a sovereign Jewish state, but its goal of fashioning a Jew very different from the (in early Zionists’ eyes) weak, passive, often victimized Jew of Europe.

Most people (myself included) argue that in creating the “new Jew,” Zionism has been extraordinarily successful. But “not so fast,” argued Professor Zeev Maghen, of Bar Ilan University, in a provocative, intentionally humorous, and entirely not PC blog in The Times of Israel. Entitled “Let’s get physical: Or why Jews should stop 'condemning violence in all its forms' (and start buffing up),” Maghen argues that Jews’ commitment to western values and its embrace of non-violence at all costs is causing Israeli Jews to cede the public space in Israel, and large swathes of Israel itself, to an Arab population that does not share that commitment to non-violence.

It’s a controversial thesis, one that will trouble many listeners, but Maghen raises issues that many Israelis discuss quietly, under their breath. What he has done is to surface the issue. Long-time listeners may recall that this issue of Israelis losing control of their own land has come up in previous podcasts we’ve done, such as those with Tahel Harris, a young Jewish mother who lived through the riots in Lod in May, 2021, with Yoel Zilberman, who founded “The New Guard,” and with Amichai Chikli, the MK who expressly accused Israeli governments of knowingly ceding the Negev and the Galilee to Israeli Arabs without pushing back.

It’s a difficult and painful conversation to have, one that is almost impossible to conduct without running afoul of some of the West’s current mores about how discourse should be conducted. But Maghen raises issues critical to Israel’s future, precisely the kinds of issues Israel from the Inside is committed to discussing, easy or not, comfortable or not, consensus or not.

Our conversation with Professor Zeev Maghen is divided into two. In today’s episode (the link at the top will take you to it), he offers us his diagnosis of the problem, pointing to numerous examples. On Wednesday, we will post the second conversation with Professor Maghen’s prescription for how to address it. That post will be available to paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

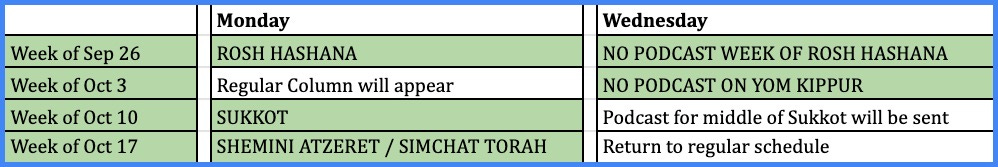

With the holidays coming up and many of them falling on Mondays (our column day) and Yom Kippur on Wednesday (podcast day), here is the tentative schedule for Israel from the Inside for the weeks of the holidays:

In the course of many of the conversations that we've had as part of this podcast series, we've raised time and again this concept that is core to Zionism called the New Jew. Many people think of Zionism primarily as a political revolution. The idea was we're going to create a Jewish state. Herzl's book that lit the fires of Zionism, which was published in 1896, was called “The Jewish State”. Statehood was for not all, but for most Zionists, always a major agenda of what the Zionist revolution was going to be about. But statehood was really only part of the story. Part of what the early Zionists and later Zionists as well wanted to do was not only to create a sovereign Jewish state, they actually wanted to change the Jew. They called it a new Jew. They were not at all hedgy about how distraught they were about what had become to the Jews of Eastern Europe. This is long before the Holocaust, but this image of Jews always looking over their shoulders at best and being attacked at worst, and having relatively little ability to defend themselves, led to a kind of an explosion of a sense. Herzl said that we need to live in a place where we're not going to be pressured to assimilate. We need to live in a place where we're not going to experience antisemitism. Max Nordau spoke about muscular Jews. Haim Nachman Bialik, in his poem “The City of Slaughter”, has a very painful scene in which he describes this horrible program and a graphic rape scene which we won't go into, and the men are hiding behind casks as their wives and their daughters are being abused in the most horrible way. This is a theme that runs through lots of Zionist thought and even contemporary Israeli thought. When you hear every year on Yom HaShoah from the prime minister, it doesn't matter who the prime minister is, left or right, male or female, makes no difference. The prime minister always says something on Yom HaShoah like if we had been a state, then that wouldn't have happened. And there is a sense that there's a kind of a new Jew who protects herself or himself, takes care of Jews in other places, which we've seen recently in Ukraine and so forth. Now, if yes, most people, has the New Jew idea been successful? Obviously, nothing is completely successful, but most people, I think, Israel and non-Israeli alike would say, yes, I mean, you look at those black and white pictures of the survivors of the programs, and that's not what Jews look like today, even after, God forbid, when there's an attack on the streets of Tel Aviv. What you see on the street is lots of armed young people, men and women, and the border police and other units going out there to hunt down the person who did this. In other words, we couldn't prevent every single death from occurring, but there's a sense that Jewish blood is not cheap anymore and you're going to pay a price. And there's a very different reaction, obviously, here in Israel than there was in Europe. So many people think that in lots of ways, the new Jew has been very successful. The new Jew is culturally creative in ways that would have been unimaginable just six, seven, eight decades ago. I always think when I walk into an Israeli bookstore, and I see hundreds of linear feet of books in a language that just over 100 years ago, nobody spoke, nobody really spoke that language. And everybody in the world who spoke that language could have fit into one of the hotels in Tel Aviv today. Not an exaggeration. In other words, we've transformed the Jews in many different kinds of ways. But I came across a piece in The Times of Israel written by my friend and colleague Zeev Maghen, who we're going to introduce in just a second, who argues in a very provocative, and I think compelling, disturbing way, that the idea of the new Jew is not nearly as successful and whole as we ought to imagine. And he points to several dimensions of Israeli society which suggests that this new Jew who's fearless and takes care of herself or himself is not quite as ubiquitous as we might think. So, I asked Professor Maghen to join me in conversation today to talk about his piece. If you print out his piece in The Times of Israel, you're going to need 35 sides of a page. So, it's a long piece. We're going to distill it into a conversation, which might be easier for some people. But I do urge you to read the piece if you have the time, because he writes brilliantly and it's very worth to read.

Zeev Maghen is the author of a very well-known popular book in English called “John Lennon and the Jews: A Philosophical Rampage”. That's his title, published by Toby Press in 2015. He's also the author of several academic books. He speaks Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Russian and English. He is a Professor of Arabic Literature and Islamic History and Chairman of the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at Bar Ilan University. He also serves as a senior fellow at Shalem College, where I work. And he was really the creator and founder of our Arabic language program at Shalem, which is, I say this objectively without question, the best Arabic language program in the country. And he is also a fellow at the Begin Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. So, a highly accomplished person, a deeply thoughtful person, a fabulous writer. Ze’ev, thank you very much for taking the time to chat today. And let's dive in. You point to what you say is a serious problem, and you begin by talking, for example, about Tel Aviv University. Tell us a little bit about Tel Aviv University. Let's understand what the problem is.

Well, the last thing in the world that I want to do is belittle the new Jew. It was a fantastic achievement, probably unprecedented in the annals of human history. I was exposed to the new Jew for the first time when I was in fifth grade. I attended the Solomon Schechter Day School in Philadelphia, PA. And every year, the principal would get us together in the auditorium and tell us about the two rules. We had to learn them by heart so that we could recite them in our sleep. And the two rules were, first of all, you do not leave campus. Because we were in a very bad neighborhood. Wynnefield, Philadelphia, Irish neighborhood. Nobody there liked us very much. They used to throw pennies at us. The teachers would make a kind of a gauntlet so that we could walk from the school bus into the campus without getting molested. Be that as it may, rule number two was that if you left the campus grounds by accident and you were accosted by any of the local boys, and they called your names or even beat you up or stole something from you, of course you did not try to fight back. You headed as fast as you could back to the teacher and reported what had taken place. And for many years, that's what happened. In fifth grade, in came this weird looking kid. His shirt was unbuttoned down to his belly button. All of our shirts were buttoned up to the neck, and he was wearing sandals, which is something that only girls did. And we didn't understand what this creature was. It turned out to be the first Israeli we had ever met. And to make a long story short, we got friendly with him. I learned Hebrew from him. And one day we were having this philosophical conversation during recess, and we were so into it that we didn't notice we had left campus. And the way that we discovered our transgression was by banging into this wall of Irish kids. And they saw that one of my friends had a new watch. And they asked the kid what time it was and grabbed the watch and put it in their pocket. They didn’t even give us the dignity of running away. And we, of course, did what we had been trained to do as good Jews. And we turned around to walk back to the teacher and weep our eyes out. And as we were walking back, we noticed there were only three of us. Where was Eran? And we turned around and we saw a scene that has never left my mind. Two of those Irish kids were already flat out on the street. The third one was ingesting Eran’s foot. He was doing some kind of a taekwondo move. And the fourth one was running down the street as fast as his legs could carry him, yelling that the Jews had gone crazy. And Eran came back and Billy Jack style dusted off his shoulders, his shirt, and he gave the watch back to my friend. And it's not that we had never seen this on TV, but we had never seen a Jew do this before. And this was one of the things that led to me making Aliyah years later. Where, by the way, unlike Philadelphia where I grew up, if a Jewish mother and one of the kids walking behind her fell down and started to cry, of course she would run back and caress and kiss and say, “poor little boo” and everything. If you come to Israel to this day in Hod Hasharon, where I live, I see it every day. A mother will be walking down the sidewalk and her kid will fall down, and even if he's bawling his eyes out, she doesn't turn around. She just shouts “kum!” which means get up. And this is quite the achievement. But things are changing, and they are changing for a lot of reasons. And one of them is the impact of modern, Western, progressive notions that civilized societies need to eschew violence in every way, shape or form, including, of course, verbal violence, even written violence. And this has really filtered and percolated into Israeli society. We see this in many places, but with us it's much more problematic because we're surrounded by neighbors who have not been infected by the progressive bug, whose civilization still, whose culture still has concepts like honor and is very physical and is very violent. And as we make ourselves less and less violent and this begins in the kindergartens, and it goes all the way up, as you said, to the university. And there was a demonstration at Tel Aviv University about two or three months ago in which a large number of Arab students and a few of their Jewish leftist colleagues brought Palestinian flags for the first time, I believe, in Israeli history to this mainstay of Israeli higher education. And they demonstrated there. It was on the day of what the Arabs call the Nakba. And a Jewish female alumnus, who had seen this and gotten upset about it from her apartment across the street brought an Israeli flag over and she started to wave it back and forth and make her own little personal protest. And she was called a lot of very bad names in a lot of languages, but she went on dancing and finally one of the Arab students jumped her and grabbed her by the shoulder by the midriff, grabbed the flag out of her hand and threw it on the ground. And you hear in the background some of the Jewish students saying, “take your hands off her, leave her alone”, but nobody interferes. And she was wrestled to the ground until the riot police actually showed up 30 seconds later and separated the two. Now, if the situation had been reversed, if a Jewish man had manhandled a young Arab lady or a middle-aged Arab lady or an old Arab lady or any Arab lady, you can be sure that the hand that he used to touch their Muslim sister would have been mangled beyond recognition and he would have been beaten to a bloody pulp regardless of the consequences that would have been for the attackers.

There were students who actually resorted to Zoom rather than coming to campus for fear of being assaulted. Was that as a result of this?

Yes, after this incident there were reports and in fact, I was told by students and even colleagues at Tel Aviv University that the atmosphere there was becoming one that frightened Jews. Now, the idea that Jews should be frightened in… I mean… you can't get any more central than Tel Aviv University. And the fact that Jewish students in the Jewish state where we were supposed to come after 2,000 years of depredations and of huddling together next to the ruler so that we wouldn't be pogromed to death, and here we come back to our own country and our students are afraid to go to the campus. And this is something that we find in other parts of the country as well. I pointed out in the article something that I grant you is not easy to talk about, but I have a student who runs a water park 30 minutes from Tel Aviv and I said to him, “Hey, I'd like to bring my family up to the water park for a day of fun in the sun. And he said, “Well, I don't recommend it.” And I said, “What do you mean?”

He said, “Well, the clientele at the water park has shifted over the past five years from 80% Jewish to 80% Arab. And I said, “Why is that? And he responded that the Arab kids are rowdy and violent and the Jewish kids and their parents and their schools are afraid. And because of that, the entire water park now serves primarily the Arab population. This is not just of that water park now. This is a situation that not only can the authorities not do anything about it. You can barely talk about it because it's politically incorrect to talk about. Because it could be interpreted as racism to talk about it. But it's a fact of life and a social game changer. And it is a microcosm that can be analogized to the macrocosm of the Negev in the south and of the Galilee in the north. Where all types of protection rackets and Jews being beaten up and lynchings almost and then car jackings and whatnot are slowly causing a flight of Jews from those areas to the comparatively safer center.

Just to put a finer point on it, if Zionism was about the return to the land, what you're describing now is the flight from the land. And I just want to make one quick point about the water park thing before we come back to the Negev and the Galilee, which is critically important. You said that the young man at the water park was your student who recommended that you not go with your kids. I can tell you I never thought about it this way until I read your article, but my kids are in their 30s, so we have not taken our kids to water parks in a very long time, 15 years, 17 years, whatever it is. But I remember already when they were younger there came a point when we were thinking about what are we going to do on this day or that day off? We would think about a water park. We think about Sachne, which is a well-known national park that has a natural spring and a place to swim. There came a certain point where we just sort of said to ourselves, “Nah”, and I never really thought about why we wouldn't go until I read your article a decade and a half later. It was not pleasant. You were nervous. You never got to really just relax the way you want to relax when you take your kids out for a day. So, I think that these are really critically important things, and I've actually experienced it even a decade and a half ago. It's not the last five years. It's been going on for a much longer time, gradually. And not going to a water park is not the end of the world. It's not a good thing, but it's not the end of the world. What happens on a Tel Aviv campus is much more problematic. If Jewish students are going on Zoom because they're afraid to go to campus, that's insane. But what's going on in the Galilee and the Negev, I want to hear you talk about more, people just need to understand what this is all about. I mean, again, this notion of returning to the land has turned into flight from the land. Jews are moving out of these places. Tell us more about it.

Well, you know, it begins not with the issue of violence, but long before that, with the fact that Jews in Israel were originally supposed to fill out the wide bottom of the labor pyramid and kind of get back to all of this physical labor, this manual labor, this plowing the land, all those kinds of things that really were at fundamental transformations that Zionism brought about. Well, when you look at what happened to them, the old Jewish ways that evidently sunk into our DNA over 20 years of exile have come back and we end up preferring to be indoors, to be up in our skyscrapers, to be on the internet breathing perfumed air.

I want to read what you wrote here because your language here is so compelling and so beautifully done and frankly, so provocative. I’m quoting you now. “Zionism emphasized, “Back to the land”, “Hebrew labor” and Aaron David Gordon's imperative to “open a new account with nature” now that we were “back home” and no longer had a huddle behind closed doors for fear of the surrounding gentile population as we did in exile. In flagrant betrayal of all this. Jews in today's Israel are mostly found indoors breathing pumped, perfumed air and working and playing on the Internet in their skyscraper offices and apartments. Far from the earth and from physicality, whereas their Arab cousins are mostly outdoors, breathing the air of the Land of Israel, working its fields and frolicking in the ponds, their muscles straining and getting stronger as they move our freight, prune our trees, collect our trash and produce our food.” You go on a lot more after that, but it's just so compellingly written. Now, we're going to talk about the solution to all of this in a separate part of the conversation, we're not going to do that now. But there is a way, though, in which this is actually, of course, a byproduct of success, right? In other words, the grandchildren of the people who plowed the land are more secure, are wealthier, can travel the world, can afford experiences that their grandparents couldn't afford. And part of that life is taking the elevator up in a skyscraper and coming back down at the end of the day and hopping into your Audi or whatever and going to Ramat Aviv Gimel or wherever you happen to live. Part of it is a success, no?

One of the things that I tried very hard to argue in this piece is that the success breeds failure. The higher the level of civilization, the more that we rely on proxies and on superior firepower in order to hold down the population that is becoming physically stronger. And that is very irredentist and secessionist and really wants us out of here. And so, what happens is, if you've got 200 or 500 or 1000 Arabs coming out onto the street to demonstrate or to riot, instead of 200 or 500 or 1000 of their Jewish compatriots coming down out of their buildings and houses and confronting this Arab mass on equal terms and basically looking them in the eyes and saying, “We're just as tough as you, if not tougher”. And that really is what we were for many, many years. Instead of that happening… If that were to happen, not only would things calm down, but there would be a sense of mutual respect eventually. There would be some skirmishes at the beginning. But eventually this meeting on equal terms and seeing that the Jews do not need to resort to high technology. You know, all of those trucks with their fire hoses that remind us of Selma, Alabama. And the billy clubs and the riot gear. By the way, many of those trucks and whatnot manned by Arabs themselves. In other words, if you look back at the Roman Empire at the end, the use of barbarians and I'm not making a comparison, I’m just using the terms that the Romans did, the use of barbarians to protect the borders of Rome from barbarians. And one of the phenomena that anyone who lives in Israel knows about is that more and more often, at the country club, at the hospital, at your children's school, even at Independence Day celebrations, Arabs are guarding us against Arabs. And the Jews, when the Arabs are coming out on the street, they prefer to go up into their high rises and close the doors and the windows like we did in the pale of settlement when there was a pogrom and leave it to the enforcement arms to take care of it. But this doesn't work because the enforcement arms can't be there most of the time. Jews are getting beaten up when there are no police around. I think the most famous of the genre is Israel's fiercest general Rehavam Ze'evi, whose grandson became religious, and there's a video of him from maybe four or five months ago on his way to the Western Wall to pray. And he is set upon by five or six young Arabs who knocked him down and kicked him repeatedly and throw his hat across the way and stomp on top of him. And then they move on, and more Arabs come by and jump on top of him. And he doesn't try to fight back at all. And when it's finally over, he just gets up and he picks up his book slowly and looks around for his hat. And this, when I saw that, I said, “This is the grandson of General Rehavam Ze'evi who put the fear of God into Syrian and Egyptian soldiers in quite a few wars”. It is a little symbolic of what's going on here and it does lead to an exodus of Jews from the Galilee and from the Negev. And once you've got that exodus and you've got a majority of Arabs in the Galilee and the Negev and we are democrats, we're not a dictatorship like Syria, then eventually we're going to have a hard time refusing the demand for self-determination from the people who live in those areas and that will be the end.

What I'm trying to say is that there's this sense that the first world civilizations have that leave it to the law enforcement, leave it to the police, leave it to the army and give them the kind of technology necessary and they'll be able to keep the masses at bay. But what really happens is that they can do that at certain times and in certain places. And even that is problematic because it looks terrible, and it reeks of weakness because you have to hand over the patrol of your streets to official agencies as opposed to going out and just confronting your neighbors on equal terms. But what eventually happens is since these agencies, these enforcement arms can't be everywhere all the time, in fact they can barely be anywhere most of the time. So, life is made much more uncomfortable for the Jewish citizens in the north and in the south and eventually they start to move out. When they move out eventually when there are so many Arabs in those areas because we're so civilized and democratic and liberal, how long can we say no to people who, let's say, make up 60% or 70% of the residents of a particular area when they ask for self-determination? How long can we say no? If we want to maintain the state of Israel, we have to maintain a Jewish presence in all of the state of Israel. If we want to maintain a Jewish presence in all of the state of Israel the Jews that are there have to be as tough on a physical level as their Arab neighbors. Now, I don't mean that they have to be barbarians. I don't mean that they have to behave in some kind of boorish fashion. I think it's possible, if you circumvent all of the propaganda of modern-day progressivism that tells you that you can't be both enlightened and tough at the same time because enlightened people eschew violence of any kind. Well, that's just not the way our neighbors live. It's not the way they think. And people who find words hurtful and who need to go and heal themselves or go to a safe space or, I don't know, go into therapy because of something they read or something they heard, let alone some act of actual physical violence, are not going to be able to stand up to a culture that is still brutal and very physically oriented.

Okay, now, there's a lot of things that you've said here that I'm sure some of our listeners are just having trouble swallowing because to call another culture brutal is part of what we don't do in the Western world. I'm not critiquing you, I’m just sort of trying to intuit where I think some listeners are right now. And we're going to talk in the second half of our conversation more about what you think really needs to change in Israeli society, educationally and otherwise. We'll come back to that. I just want to remind people that we did an interview a few months ago, maybe a little bit longer, with Yoel Zilberman, who is the founder of HaShomer HaHadash. And Yoel Zilberman founded this organization of young kids actually patrolling areas where the police can't get to because as he tells it, his father's own farm and vineyard was being lost to Arabs who were taking protection money. And his father told his kids, I'm just going to get out of this business because I can't make a living. I have to pay so much protection money, the farm can't sustain me. It's just over. And Yoel who was just getting out of the army from an elite unit, said, that's just not the way this is going to go down. This is going to go down in a very different way. And he took an Israeli flag and a stack of books and a little tent and a gun. And he started sleeping out on the edge of his father's yard or field or whatever it was, and people got a very clear message. And then he realized that if he can save his father’s farm, but the police couldn't, if he could get tens and then dozens and then hundreds of young kids to read all AD Gordon and read Max Nordau and read Herzl, but in the evenings and the afternoons patrol. Sometimes in partnership with the police. Sometimes some people think not in partnership with the police. We'll just leave it that way. He's changed the reality for hundreds of Israeli farmers who have lost their land. But as you point out, there are huge swathes of the Negev and the Galilee that are still being lost and it's not becoming really a national conversation. Our listeners who heard Amichai Chikli, he spoke very openly that he felt that the Netanyahu government and the Bennett government were failures in terms of trying to protect the Galilee and the Negev. So, I just want to make it clear to people who are listening that what Professor Maghen is saying here is not Professor Maghen’s singular perspective here. We've heard other people talk about this as well. It's a well-known problem that is not eliciting national discourse. Everybody knows what's going on and nobody really wants to talk about it because it's very hard to talk about it, as you said, in ways that sound politically correct, in ways that sound non-offensive, in ways that sound non-racist. So, we're going to wrap up this part of the conversation now and in the next part of our conversation, we’ll hear more about your sense of what we can do. How should our kids be educated? What has to change about Israeli society? Can it really happen? We're going to pick all that up with our next conversation.

Impossible Takes Longer, which addresses some of the above themes, will be published this April. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

"Let’s get physical"