Before we get to our main subject for today, we’re sharing this video, making its way around Israeli social media in English (so you may have seen it), which is part of Israel’s attempt to win hearts and minds in a period in which that seems essentially impossible to do.

WARNING: it has some unpleasant images.

And now, for today’s podcast ….

With the war a month old and showing no signs of ending, we, like many others, are beginning to creep back to a grudging sense of pain-infused normalcy. Today we revert to one of our podcasts, one which we recorded before the war began.

Martin Indyk’s tweet above, from September 12, didn’t age well. It didn’t even make much sense the day it came out, obviously, for the antisemitism at the heart of the Palestinian cause was obvious even before their murderous, sadistic rampage of October 7.

In his book, Landes shows he he was not surprised by October 7. Here’s a lengthy quotation from the Nobel prize winning author Jose Saramago, denouncing Israel in 2002:

Richard Landes started out as someone who was in favor of Oslo, then he realized what was really happening and believed it to be a huge mistake. By now, I assume that it’s fair to say that most Israelis agree with him.

But they—like us—don’t know a fraction of what Landes does about the Jihadi world, which he shares with us in his book.

Richard Landes is a Historian of the Middle Ages, a Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Millennial Studies at Boston University. He is also the chair of SPME’s Council of Scholars. His latest book is called Can “The Whole World” Be Wrong? Lethal Journalism, Antisemitism, and Global Jihad.

Richard received his master’s degree from Princeton University and his Ph.D. from Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. Today he lives in Jerusalem.

The link at the top of this posting will take you to the full recording of our conversation; below is a transcript for those who prefer to read, available specially for paid subscribers to Israel from the Inside.

All of us listen to podcasts in different kinds of settings. Some of us are in the car driving. Some of us are out in the woods taking a walk, maybe. Some people are on their bike. I'm not quite sure how smart it is to be riding your bike with headphones in, but that's another conversation altogether. And some of us, I think, listen to podcasts kind of, you know, we're getting a little tired at the end of the day or whatever, and it's a good time for a podcast. This is not a podcast that I would encourage you to listen to right before you plan to go to sleep. We are with a person who is incisive, very clear in his views, a very pithy writer, and someone who I always learn from and fascinated by listening to, Richard Landes. In the technical side, Professor Richard Landes was trained as a medievalist, and he taught in the History Department in Boston University. He's now an independent historian living in Jerusalem. His work focuses on apocalyptic beliefs at the turn of the first millennium, spoke the peace of God and the second millennium global jihad and woke. Richard, we're going to have you introduce yourself in a second, but the book, which runs about 500 pages, little light reading for a Shabbat afternoon, is called “Can “The Whole World” Be Wrong?: Lethal Journalism, Antisemitism, and Global Jihad”. So, we could save people the time and say the answer is yes, the whole world could be wrong and save yourself the 500 pages, but they shouldn't because there's a lot in here, a lot of fascinating stuff and depressing stuff in here. So, tell us a little bit more about yourself, first of all, before we go on. More than I just read to our listeners.

Well, I think two of the most important things about my training as a medievalist is that, first of all, I work on a premodern society and as a result, have a sense of the kinds of mentalities, I consider myself a historian in the Anal Maltalite School, the mentalities that drove people in earlier periods, which I think we moderns almost can't imagine, or I might say, won't allow ourselves to imagine. So, on the one hand, that means things like shame on our culture, in which it is expected, even required, that you shed the blood of someone, could be your own, for the sake of honor. And these are things that we have not overcome in the sense that nobody wants to be shamed and everybody would like honor. But on the other hand, we don't believe that it's something that you kill for, whereas in some cultures it is.

Oh, we have that problem in Israel in certain parts of the culture, actually.

Exactly.

Okay, so now let me ask you a question. So, you're trained as a medievalist, right? You're trained in these cultures, which are, I would say, and you help me if I'm wrong, very non-Western, very dissimilar from the cultural assumptions that we make today, whether we're European, North American, South American, any part of the west. How in your own life story does a person who's trained as a medievalist end up spending so much time on what seem, on the surface at least, to be profoundly contemporary issues? I wouldn't say modern because they're not really modern. They're premodern a certain way. But just in your terms of your own life story, I mean, imagine you're doing your doctorate, you were planning on talking about people who lived 1,000 years ago. Right?

And still are. After finishing this, I've gone back.

Okay, that's interesting. Maybe we'll have that conversation sometime. But you took a very long detour right away from writing and researching people who lived 1,000 years ago to writing and researching people who are alive right now. Why?

So that's the second component of my training as a medievalist, is I worked on apocalyptic movements. Apocalyptic movements, millennial apocalyptic movements are movements that expect either the last judgment imminently. Imminent is the key thing. Or they expect the kingdom of heaven to descend on Earth. So, my previous book to this was a book called Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience, the last chapter of which is dedicated to global jihad. So how did I come to this? In 1994, 95, I was here…

Here being Jerusalem.

Here being Jerusalem for the year. It was the beginning of Oslo. Everybody was very enthusiastic. Or not everybody, but lots of people. I was. I joined dialog groups and so on. And I met a graduate student who's now a professor at Rice, David Cook, who was working on Muslim apocalyptic, the core of which was happening in the area surrounding both in the Palestinian territories, in the area surrounding Lebanon, Jordan and so on. That's where the publications were coming from. And he described to me an apocalyptic movement, which is in the categorization that I developed an active cataclysmic movement, which means that before either judgment comes or the kingdom of heaven on Earth comes, the global caliphate, in this case, a vast amount of catastrophic events have to occur. The destruction of evil to pave the way for good.

And that's things that human beings have to do?

And that's the active, because there's passive. The rapture Christians put that in God's hand, right?

Wait for it to happen.

Wait for it to happen.

Which was, by the way, very dissimilarly, but still, there are parallels here. The original attitude of the orthodox to Zionism in the end of the 19th century.

Absolutely.

You can't force history. Just wait for God to bring us back. Different argument altogether, but still some sort.

I would call that active, not cataclysm active transformative. In other words, we engage in, but we're transforming the world. We're not destroying everything inside.

Okay, so Christian apocalypticism basically argues terrible things have to happen, but we don't make them happen. God is going to make them happen. That'll be the sign that God is the Tribulation.

God brings the Tribulation, now doesn't mean that it can't flip. And there's a fantastic book by Boyer on how the people who armed the nuclear weapons were in one town in Texas and they believed that they were doing God's work, that this was preparing for the Tribulation, which would be in.

What years are we talking about?

This is the 50s and 60s. So, it is possible, but with Islam, with jihad, with global jihad, this was an open and clear case of active cataclysmic. And in the category of apocalyptic beliefs, when people say religion has killed more people than anything, first of all, I don't think so on ashamed. It's definitely killed more people than anything. But of the religious beliefs, this belief is mega death. I have a chapter in my previous book on the Taiping. When they were done with 14 years of millennial warfare against the Qing Dynasty.

In what year is this?

This is 1850 to 1864. An estimation of 20 to 35 million Chinese were dead.

Wow.

Yeah. So, once you're in this mode, there's nothing holding you back. And I think both the Nazis and the Communists and the Maoists, the Stalinists, the Bolsheviks and the Maoists were into this mindset secular, but nonetheless, we are preparing heaven on Earth.

So, what is active apocalyptic, as you're talking about, there's different categories, in this part of the world you're saying it's active?

It's active.

Meaning what?

Meaning that we, jihadis, are the agents of God in bringing about the destruction necessary to pave the way for the global calendar.

I'm just repeating. I just want to make sure our listeners understand. So, the Christian world is more passive. There needs to be fire and brimstone and destruction before the kingdom of Heaven can come.

But we're waiting for it.

But God will wait. God will bring it. We wait for it. In the jihadi world, you're saying that's not the case. We human beings have to create all the destruction, and then that paves the way for the caliphate, which is their visions of the world to come of something like that. Okay.

So then being alerted to this, I began to realize how much of the rhetoric of the Palestinian Authority reflected both honor shame and active cataclysmic apocalypse.

In what year now were we talking?

1995, 1996.

So, around the Oslo years.

Oslo years, for instance.

So, you're saying that this attitude is not in the worldview of Iranian clerics?

Oh, yeah.

The view that we would have thought is the view of Iranian clerics, clerics from Beirut or wherever, has actually infiltrated, so to speak…

Permeates the culture…

Permeates the culture of the Palestinian Authority, with whom Israel at that point is negotiating a deal.

Exactly. We can come back to this if you want, but basically, it's at that point that I started to get concerned. I wasn't writing a book yet about it, but I was getting concerned about the way you know, I remember Rabin, after every suicide terror attack coming on and saying, this is the price for peace we have to pay. And I remember thinking, you're not paying a price for peace. You're paying a price for war.

Well, you said you were in favor of Oslo, though…

I was initially. And then it became clear to me that whereas for us and the Americans and the Norwegians, this was land for peace. In the honor- shame world, the more concessions you get, the more you are encouraged to attack. And that for Arafat, this was land for war. And that sets up this terrible, literally contradiction in the sense that on the one hand, we want to pull off this deal of land for peace, and when it fails, we tell ourselves, if only we had given more. Whereas on the other side, the view is this is land for war. The more we get, the better positioned we are to pursue our war. And so, I became more and more upset. And then when the Intifada broke out…

You’re talking about the Second Intifada.

The Second Intifada, which I call the Oslo jihad.

Okay. Take a non-judgmental term, right.

I consider it descriptive.

Okay.

So, when the Oslo Jihad breaks out that's the point that was a sort of critical moment in which a whole series of attitudes crystallized that had been in the making before, but could have broken a different way, broke the wrong way. From the point of view of what I consider liberal, progressive, Western humanitarian values. People who want land for peace. People who want peace.

Right.

So that's when I think I started… I still didn't have this in mind. In 2005, I started a blog, and then in 2008, Charles Jacobs said to me, you got to write a book about this. It took me another 15 years. It was a mess.

Okay. Which brings us indirectly, but nonetheless to the present book, which has just come out Mazel Tov, by the way, on the book appearing, “Can the Whole World be Wrong?” Now, that's a quote, of course, from Ahad Haam really. Right. I mean, Ahad Haam is a Zionist thinker in the late 18 hundreds, early 1890s and he's basically parroting the views of the world. Right? He's saying they say about us.

Yeah, he's probably parroting the views of the Ukrainians.

Who are back in the news, but in a different way. Right. Can the whole world be wrong? Like, if the whole world hates us.

If the whole world believes that we sacrifice Christian babies to take their blood to make matzah and we say, no. Can the whole world be wrong, and the Jews be right?

Okay. So now, how is that question relevant? This is can the whole world be wrong? It's not about babies and blood and matza anymore today. Give us kind of the soapbox version of what's the thesis?

Right, so, that quote comes back in 2002 when the press is reporting across the boards a massacre in Jenin, and there are articles about Israeli genocide from high minded British thinkers in high minded British papers and so on, accusing us of genocide in Jenin. And the head of the UN, Kofi Anan, says, I don't think the whole world can be wrong and Israel be right. He didn't even ask a question, wasn't even a rhetorical question. For him it was open and shut. We're doing what the Palestinians say we're doing.

When of course, we know now it's not even a matter of interpretation. We weren’t.

We weren't. We were doing the opposite. There's no three-week urban battle that's taken place in modern warfare in which three to one, the militants are the casualties and the civilians to the civilians. It's normally the opposite. So, this then plays into and I think one of the themes I'm trying to get across in my book is that what's happening in Israel, Israel is, if you will, patient zero or victim zero or target zero. In other words, what happened here, in 2000, jihadis, and I think that if you listen to what they say, if you follow MEMRI and Palestinian Media Watch, these are global jihadis. They just happen to be on this battlefield, but they're part of a global jihad. Hamas definitely. Jihadis are attacking a democracy, and everybody agrees it's the democracy's fault, it's Israel's fault. And when the attack on the United States happens in 9/11, you've just been through this hate fest at Durban, which prepared world opinion to turn against the United States. So, ten days after 9/11, you've got a major French thinker, Baudrillard writing in the Le Monde saying nobody who loves freedom can't rejoice at what happened at 9/11, striking so suffocating a hegemon as the United States.

Okay, so now we're in 2001 is the attack on the United States, 2000 is the beginning of the attack on Israel.

Right. 2001. So what happens is Reuters and BBC refuse to use the word terrorism to describe it.

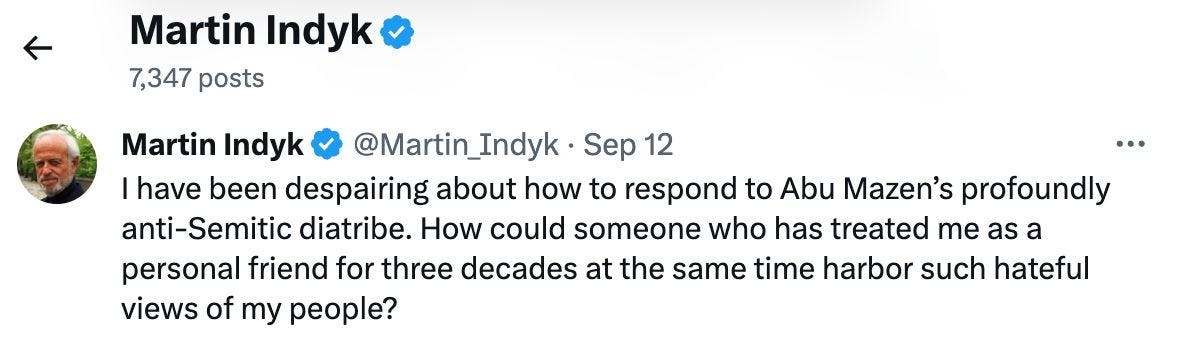

Okay, now I want to go to 2002, I think it is, with Jose Saramago.

Yes.

Okay, it's a bit of a long quote, it's a full paragraph, but I do want to read it, and we have it up for our listeners in the post in which this podcast is disseminated. It's on page 13 of the introduction of your book. I just think it's really important to read it, because you're commenting on it, I think, will actually cut through to a tremendous amount of what this book is about. It's not in your introduction by accident. So, here's what he says. By the way, I think he was getting the Nobel Prize then, wasn't he?

Yes, he had gotten the Nobel Prize.

So. He's a Nobel Prize winning author.

Who goes to visit Arafat in Ramallah…

And then writes: “Intoxicated mentally by the messianic dream of Greater Israel, which will finally achieve the expansionist dreams of the most radical Zionism. Contaminated by the monstrous and rooted certitude that in this catastrophic and absurd world there exists a people chosen by God. And that consequently, all the actions of an obsessive psychological and pathologically exclusive racism are justified, educated and trained in the idea that any suffering that has been afflicted or will be inflicted on anyone else, especially the Palestinians, will always be inferior to that which they themselves suffered in the Holocaust”.

This is just amazing line. “The Jews endlessly scratch their own wound to keep it bleeding, to make it incurable, and they show it to the world as if it were a banner. Israel seizes hold of the terrible words of God in Deuteronomy, vengeance is mine, and I will be repaid. Israel wants all of us to feel guilty, directly, or indirectly, for the horrors of the Holocaust. Israel wants us to renounce the most elemental, critical judgment and for us to transform ourselves into a docile echo of its will. Israel wants us to recognize de jure what, in its eyes, is de facto reality, absolute impunity from the point of view of the Jews [all Jews, he seems to suggest, not some Jews] Israel cannot ever be brought to judgment because it was tortured, gassed and incinerated in Auschwitz.”

Okay, that's not for the faint of heart either. What's the argument of your whole book in response to Saramago? Because in a certain way, I mean, this is a very intricate, highly learned, very dense, at times response procession. So how is your book a response to, what are you saying that we should know about Richard Lande’s response to Saramago?

So, actually, the next paragraph, and I encourage you to put it up as well, is me restating what he said if it were about the Muslims and the Palestinians…

Which you could never say…

Well, what I said is and although this is far more accurate about the Palestinians and the Jihadis than what he said about the Jews, what he says can be shouted from the rooftops of major publications and what the counterfactual case is utterly silenced. And that, I think, is the core of how the world can be wrong. In other words, you've got this especially the sort of scratching the wound, which is what the Palestinians do with the Nakba, and making people into docile expressions of their will, which is what the Palestinians were doing after 2000. And yet he's falling fully for it and turning the fury of his supersessionist, I mean, this whole thing about the Jews and the chosen people, one of the things I have an article coming out in a journal of anti-Semitism soon about progressive Supersessionism, there's this projection that supercessionists have in which they project onto Jews the nastiest supercessionists, they project onto Jews their notion of chosenness, which is we get to rule the world and nobody we're unaccountable onto the Jews and then hate us for their projection. And that's exactly what Saramago is doing there. And that, I think, since 2000 and since the response to the Oslo Jihad in which, I'm afraid, Israelis, I think, mostly of goodwill have participated, as I put it, they're holding up the train of this icon of hatred. It's not the emperor’s new clothes, it's the emperor's new hatred. And we're holding up the train in this procession in which, if only we had been better, it would have worked out.

You think Israelis still think that? I mean, now we're having this conversation in 2023, obviously, there might have been Israelis. There was a left, for example, in the days in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s and then the whole Oslo thing gets going, there was an Israeli left. There's really no Israeli left anymore. There were people then, I think, who were saying, if only he had done or we had done more, we had done better. Do you think that voice still exists in a meaningful way vis-à-vis the Palestinians in Israel anymore?

Well, yes and no. I mean, let's take, for example, let's take Ehud Barak.

But I think Ehud Barak in fairness, I think Ehud Barak…. I want to actually say that we're going to leave Ehud Barak out and I'll tell you why. Because I don't think Ehud Barak, who was in 2000 obviously Prime Minister and negotiating and so on and so forth during the Intifada, which you're calling the Oslo Jihad. I just think that Ehud Barak has become less of a representative of the mainstream left in Israel, particularly in the last half of years, in light of the positions that he's taken about the Netanyahu government. I mean, I see a lot of people who are further left than well, a lot of people that I know who are actually not citing Barak anymore because they think he's kind of gone off and done his own thing so, I want to talk about the rank and file or let's go this way. There's been over the last year in Israel, right, millions of people altogether, some total protesting in the streets in Tel Aviv on Kaplan every Saturday night. There are hundreds of thousands of people out there, and many of them are what one would call the Tel Aviv secular liberal Israeli. Tell me if I'm wrong. I think that most of those people no longer are doing an Al Ḥeit. They are no longer beating their breast about Israel's handling of the Palestinian initiative and saying, oh, if only we had done more, things would have worked out better. My sense and you might disagree with me, which is totally fine, but my sense is Israelis aren't there anymore.

No, I would agree with you, but the damage was done on a massive scale. There was, after 2000, a whole bunch of sort of what did they call themselves? Post Zionists, went to the West, poured their vitriol into the academic...

Well, those are really sort of the new historians.

Right, new historians and so on, but also, I mean Peter Beinart…

But I want to come to Peter Beinart a second, because I want to actually ask you about American Jews separately.

So, what I’m saying, though, in the mind, what happened then, and what I would say is the shift has been a largely silent shift. In other words, there's no grappling with what went wrong. There is, I mean, people grapple with what went wrong, but I don't think they get at the core of what went wrong.

What went wrong?

What went wrong, I think, was that, look, as I said at the beginning, I was for Oslo. After a while, I turned against it or was critical of it and worried about it. You can argue we had to try it. It's a legitimate position to take, and we had to take the risk. But two things happened during Oslo and got worse after Oslo that had a huge impact on the West. One was the willingness of Israeli journalists to engage in fake news. You know, that's what we call it now. But then it was called peace journalism, in which Arafat's speech in Johannesburg about this is the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, barely got covered, when Dennis Ross writes his memoirs, or when Charles Allen writes his memoirs of what happened, there's no Hudaybiyyah in the index. They don't discuss it.

What is that?

The Hudaybiyyah speech was basically, look, Muhammad made a treaty with the Meccans when he was weak, but as soon as he was strong, he turned on it. And that's what we're doing. We're weak right now, so we're using this. It's a Trojan horse. And that theme got buried when the PLO was brought together in, I think, late ‘95 or early ‘96 to change their charter according they didn't. The news reported it as if they did. So, on the one hand, you have this corruption of the news. There's an interview with Yigal Carmon said he went to Nahum Barnea and showed him the stuff, and Nahum Barnea said, look, you're doing this because you're against peace. I'm for peace, so I'm not going to cover this. So, on the one hand, you have the news media betraying the public because they're promoting a cause which they think is worthy. And the second thing is they demonized the opposition. So, anybody who spoke out against it was a warmonger. Anybody who spoke out against it was a right-wing fanatic and got lumped with the worst of the settlers and stuff. And when the warriors came out, the suicide bombers came out of the Trojan Horse of Oslo, instead of saying, mea culpa, we really got this wrong, the attitude was if only we had given more. And I think there's lots of people who are still saying, if only we had given more.

Okay, I mean, maybe there are… we might disagree about that a little bit, which is totally fine. I think if somebody went to Barnea right now and said the same thing, he would not respond that way. I think if there were… I mean, look, let's say Arafat, I mean Mahmoud Abbas, but that was actually a Freudian slip. But okay, Mahmoud Abbas just gave a revolting speech within the last he did it back in September, right? And the Holocaust was animated by the Jews, and there are money issues and so on.

Nothing to do with anti-Semitism.

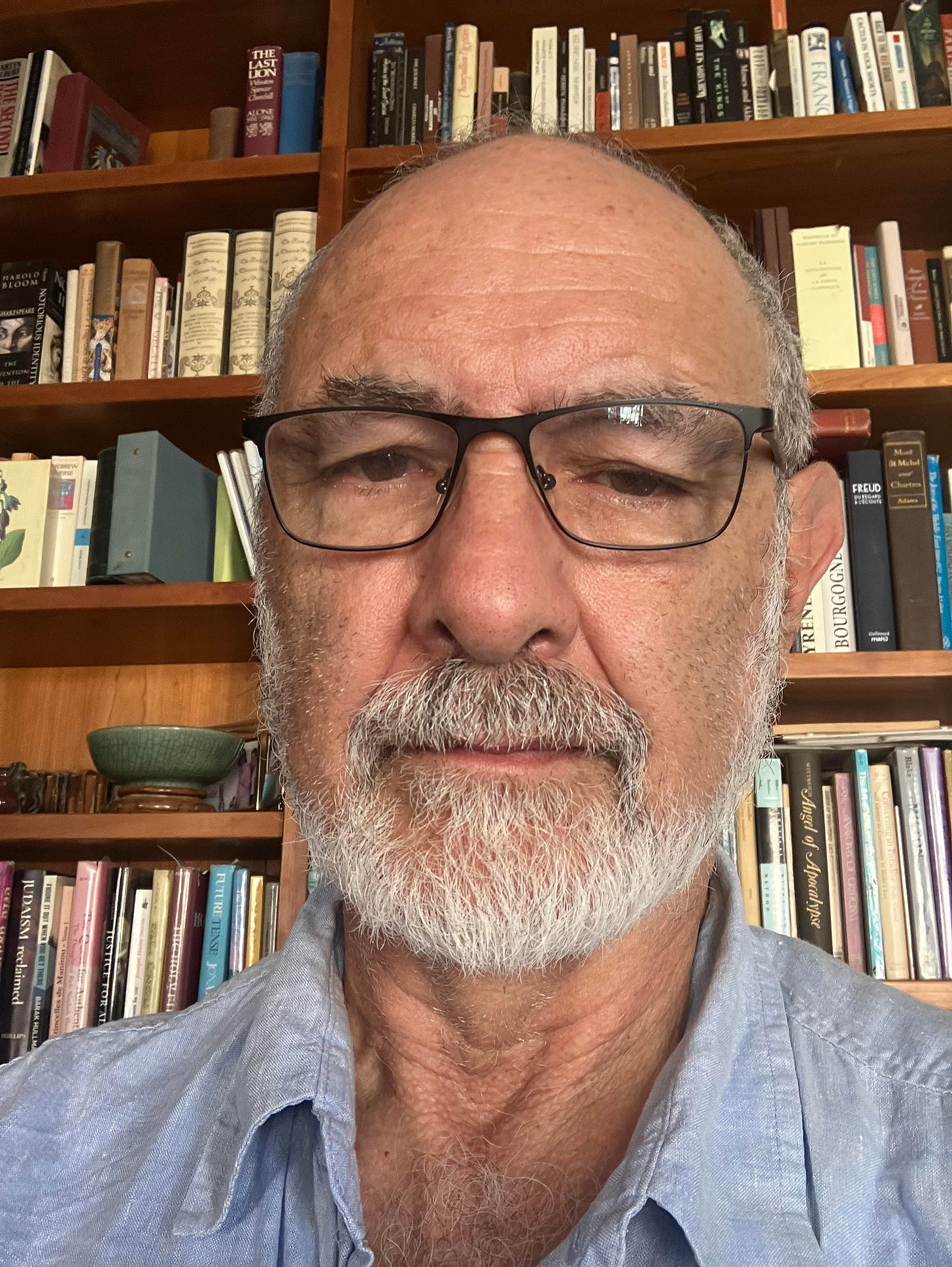

Nothing to do with anti Semitism. I mean, really, the worst of the worst of the worst. And this is actually just going to feed into your thesis. Shortly after that, Martin Indyk, a very well-known American diplomat and so forth. Major player. He tweets on September 12th, which is a few days, I think, after Abu Mazan and Mahmoud Abbas called him what you wanted, said what he said. Martin Indyk tweets, I have been despairing about how to respond to Abu Mazan's profoundly anti-Semitic diatribe. How could someone who has treated me as a personal friend for three decades at the same time harbor such hateful views of my people? So, I want to ask Richard Landes, what's the answer to that question? How could someone who treated Martin Indyk as a friend for 30 years harbor such horrible views of Martin Indyk’s people? What's the answer?

The answer is that this is somebody who's operating according to the rules of an honor, shame culture in which, in order to save face and in order to advance your cause, it's perfectly legitimate to pretend to stuff and Martin Indyk got taken in. I mean, Gidi Grinstein, in his interview with you and apparently in his book, emphasizes the deep trust that built up. Well, yes, but that trust for us is existential. For them, if conditions change, it doesn't have the same meaning, and we can't… I mean, one of the things that's really striking about how the media covers this conflict and I have a quote from Andrea Koppel about know it was at the height of the Jenin stuff. Journalists hadn't been allowed in yet. Andrea Koppel hasn't even been to near Jenin. She just landed. She's in Tel Aviv, and she's talking about the Israeli massacre. And somebody says to her, how do you know? And she said, well, I heard it from journalists. He said, journalists haven't been allowed in. How do they know? They heard it from Palestinians, he said, is it possible the Palestinians are lying? And her response was, oh, so they're all lying now. So, there's this sort of… we are as good Western people of goodwill, helpless before people who will willingly lie to us.

Okay. So, I want you to push that point. What you're saying, basically, is that our… this includes the left and the right and religious and secular and Democrat and Republican and Meretz and Likud.

Okay.

It's everybody. You're saying the way that we're raised, the kind of discourse that we're trained to engage in, the way we're trained to see the world, even if we have disagreements among all of us, it fundamentally emasculates us all in the face of a culture which we just don't know how to deal with.

Exactly.

And by the way, the only people who said that were the radical right in Israel in the days of Oslo, especially the settler movement, who said, you're being taken in. And they were actually right. So, when you were in favor of Oslo and I was in favor of Oslo, both of us at the beginning, they were right about us.

Yes.

And they were right about them.

I use the term opium.

Okay, fair enough. Now I want to fast forward a little bit into the late 300s in terms of the pages of the book.

Okay.

Not 300 CE. I want to move the conversation a little bit to American Jews.

Okay.

You and I, again, might disagree. I think Israeli Jews have been weaned a little bit from this.

Right.

I don't think there's a lot of breastfeeding. Oh, if only they have done more, I think look, with the whole judicial reform thing and the Palestinian issue really didn't come up at all. There were some signs at the protests “there's no democracy with an occupation”. Those signs were few and far between. There were many more gay pride signs and flags than there were anti occupation flags. I think Israelis, even on the left, understood that whatever was going on in Israel, whether you were pro-reform or anti-reform, it wasn't about the Palestinians. So, I think that the Israeli Jews have sort of kind of weaned themselves from that. You may think I'm a little naive and a little bit more...

No, I think they've weaned themselves from it, but they haven't grappled with the consequences of the previous error. So, for instance, I think that a lot of the opposition, a lot of the people whom I respect, like Gerald Steinberg and Itamar Marcus and stuff, of Palestine Media Watch, who are clear on what went wrong back there, are highly suspicious of what's going on with these protests, in part, and I think it's even worse for people who are even farther I don't like to use right left, but who are even more hard line than they, that there's a deep suspicion that underlying this protest is a kind of desire to realign with democratic forces around the world. So, for instance, Gidi’s interview was talking about how the American policy leaders are beginning to wonder if Netanyahu is rational anymore and if he's not rational, he's unpredictable. In my read, when it comes to the Middle East, the American policy elite have been irrational for the last 20 years…

But you're talking about America. I'm talking about Israeli people on the streets. Let's go to America.

But there's a deep desire I think....

I'll put it this way. Even if we've weaned ourselves, we're recovering addicts. I'm going to mix metaphors here. You're still sort of yearning for the drug. But I want to go to America.

We're not scratching it anymore, but we haven’t…

I got you. Okay, but not scratching in the same sense as the Saramago. That's a different thing. Got to be careful how many times you use that phrase. Okay. Now I want to shift across the ocean. Not Arabs, not Israelis, but American Jews. And you lump together a whole bunch of people. And I'll read a couple of sentences. It's in the middle of an argument so, it's actually people are going to have to read the chapter to see it. But the chapter is about what you call anti-Zionist Jews, the pathologies of self-criticism.

Right. Well, you read the at the beginning of the chapter, I have a haiku.

You have a haiku at the beginning of the chapter. Okay, I'm going to flip here to the beginning of the chapter. Okay, here's a little haiku. “Have ever before lambs denounced lambs who refuse to lie with lions.” Okay, so basically, the lambs are denouncing other lambs who refuse to lie with lions…

The American Jews, the Diaspora Jews are denouncing us for refusing to participate in their messianic scenario whereby we lie down with the Palestinians, and as the joke goes, we wake up the next morning.

Right. Of course, if anybody gets eaten by the lion, it's us, not them. Okay, now so now we're going to skip a few pages, a bunch of, like, 20 pages in or whatever, and you ask the following. “Do 21st century anti-Zionist Jews like Judith Butler, Peter Beinart, Daniel Boyarin, Jewish Voice for Peace, If Not Now do this consciously? Do they know that they mimic the most sadistic memes put out by their people's most ferocious enemies and fuel those hatreds? Do they realize they have teamed up with a tribal notion of justice based on revenge for lost honor, on washing one's blackened face in the blood of the dishonoring enemy in which that targeted enemy is their own people, with whom they publicly identify as a Jew?” Wow. First of all, wow. That's some serious writing there. So, look, Jewish Voice for Peace has always been rabidly anti-Israel. I mean, it's been hostile to Israel's very existence from the very, very get go.

And there's a good question as to how many Jews are actually in it.

Right. It's not for peace, and it's not Jewish. It's a voice. We said that that JVP is neither J nor P. It’s just a V. But that's not true of Peter Beinart. There were days in which I was debating Peter Beinart and there are lots of YouTubes of me and Peter Beinart debating all over the place. We disagreed about politics. But that he loved Israel and cared about Israel was obvious to me, which was why I was willing to debate him, because we started out, we started out from the assumption that, yeah, the Jews should have an independent Jewish democratic state. Now, Peter Beinart has come out since and stated publicly that he is no longer in favor of the existence of a Jewish state, which is why I no longer debate him. I mean, because at that point you're the enemy of my people, and you can call yourself a Jew and all you want. You can go to an Orthodox school on the Upper West Side, which he does, all well and good, but I'm not getting on a stage with you. What happened? I don't mean him ad hominem. I don't want to talk about Peter ad hominem. But what is the dynamic here of Peter, of some liberal rabbis whom we will purposely not name by name here, who it's become almost I don't know…. It’s… They're consumed by this desire to lambast Israel beyond the relevant to me, at least beyond what policy would dictate, and they've built a whole world out of this. What's your understanding and as it fits into the theory of the book at large, as what this is really all about.

Right. So, on one level, it's important to understand that they are operating in a society in which the whole world can't be wrong.

So, they're just buying into the larger Western…

They're buying into it on the one.

So, they're saying Saramago can't be wrong.

So, they're yes, so Saramago is painfully right. I hate to think it. I hate to, but I have to admit it now, that gets at what I call masochistic omnipotence syndrome, which is.

You have a lot of syndromes I got to learn about. Okay, masochistic omnipotent syndrome.

Which is all our fault, and if only we were better, we could fix anything.

Right, but we talked about that a minute or two ago. So, I'm saying you don't completely agree, but that's okay. I'm saying I think a lot of Israelis have weaned themselves of that. And you think that American Jews and their leaders especially, but a lot of American Jewish leaders on the left are…

Are still there. And first of all, that's the sort of progressive attitude today, right? Jews stole the land. Jews are mean, Jews are imperialists. And it's such a powerful wave that it's not a question of sticking your finger in the dike anymore. I mean, when 9/11 happened, Peter Beinart was at the New Republic, which wasn't yet sort of what it's become…

Which is not much of anything…

Yes, I stopped even reading their headlines. Peter Beinart was at The New Republic and wanted a muscular, liberal response. Right. I haven't done his entire career, but he has gradually, and I think that's the case across the boards, I mean, when BBC and Reuters refused to use the word terror, there was an outcry amongst American journalists. What are you doing? But within three or four years, the Boston Globe was writing op-eds or whatever about the use of the word terror and so on. And after a while, the most anti-Western attitudes dominated. It took a while. It didn't happen right away, but over time they did. And I think Peter Beinart a really good illustration of how the force of that drive worked on Jews. And I don't want to impugn Peter Beinart by saying he wants to be popular, but he sure is popular. He's appearing on all these programs with all the wrong people.

It's the court Jew phenomenon?

In a sense, yeah, but it's the court Jew phenomenon, you know there are lots of court Jews who do it while it looks like it's helping… one of the things about this, a lot of people on the left, a lot of Jews on the left think they're being prophetic by denouncing Israel. They see themselves as right. The prophets never went to Bavel or know Assyria, and in the language of the enemies of their people, denounced their people. They did it in Hebrew to their own people. But these guys are going to the courts of the gentiles, speaking in their language really revolting stuff.

Animated by having bought into it?

Yes, I think they bought into it. I don't think that Peter Beinart is an evil person. I think he's a deluded person. Now, does he have a right to be deluded? I would say he's got a lot to do on Rosh Hashanah, but we all do.

Yeah. Okay. All right. I want to come back to one thing in a minute about Israel and how Israel should address all this. I just have to sort of sneak in here, one of the things that I noticed between, let's say, January 2023, which was more or less when the whole judicial reform thing in Israel started to get going, and let's say Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur of 2023, 9-10 months later. One of things the I noticed was and this is a separate conversation I'm just sort of musing out loud because we're having a chat. I was surprised by the way in which the rabbis on the American left did not embrace the Israelis on the streets. In other words, you didn't see fire and brimstone sermons saying for many years, it's been very hard for us to identify with Israel because we had a problem with the Palestinian thing, we had a problem with the Israeli chief rabbinate, we had a problem with the Kotel, with the Western Wall policy. But, congregation, look what's happening on the streets of Tel Aviv at Kaplan Square. That's us. That's exactly what we believe the world should be. Let's embrace them. This is our moment to take great pride in Zionism. You heard very little of that. And I think that there is a whole exploration of what you might call the silence of the progressive lambs or something like that, since you have all these catchy theories. No, but I think it's really a fascinating question. I don't want to again, I don't want to mention specific rabbis here, but why some of these rabbis who are best known for lambasting Israel left and right all the time about the conflict, when there was this massive phenomenon that Israel you can agree with it or disagree with it. Leave that alone right now. But there was this massive phenomenon of the street speaking about democracy and protecting the rights of minorities and so on and so forth. The American rabbinic left sort of said, yeah, that's good, we're in favor of that. But there wasn't this embrace. And I think that some of that is I think and again, it's not in your book, obviously, that some of this is the same thing. They have so internalized the Saramago worldview that even when there's something happening in Israel that they love and ought to want to embrace, they don't even know how to do it anymore, which to me was actually kind of heartbreaking.

Right. It's really interesting. I hadn't thought about it, but as you say, I don't use the analogy in the book, but I think that I do talk about self-criticism, which is a key element of Judaism and which my favorite thing is to say to people, I think that Jews are the most self-critical people in the world, and the response is, no, they're not. So, I think that self-criticism at one point and actually, Nick Cohen cited me in this, I said, self-criticism in public is like chewing broken glass. Nobody wants to do it. Jews do.

For us, it's a matter of pride. I have a quote from Sigmund Freud where it says it's the magnificent victory of the ego over the superego to be self-critical and so on. Okay. So, it's like dopamine for runners. You become addicted to it, and you can't let go of it. And I think that they're addicted to this position. And again, I think that comes back to the sort of whole world being against Israel. If they were to turn and say, hey, there's something we can be proud of, then they have to deal with all the people that they've been pleasing with their criticism.

Who now are not going to be pleased, or they'd have to teach them a different kind of a language, which they don't want to do. Okay, we could talk a lot longer, but we've already been going on for a bit. I just want to ask you really quickly by way of beginning to wrap up. I mean, the book is the book is a tour de force. It's depressing. It just is. It's just because it describes the Western world in ways that are really very hard to argue with, but nonetheless really overwhelmingly sad. You told me before we got started that friends of yours have told you that the book is really an ad for antidepressants or buy the book and then buy some antidepressants. I actually thought the same thing as I was reading it. It's good to keep a bottle of Scotch on the table as you're reading this book, but it's the same idea. It's a hard book to read, not because the writing is not great. The writing is just it's heavy. And even if somebody only read a third, they would understand our world much, much better. In light of what your insight is in the book, is there anything in the world that Israel could possibly do to lessen the international opprobrium other than fold?

Wow. Yeah. At one point in the chapter on Jewish anti- Zionism, I talk about how dangerous it is for Gentiles to listen to this. They love this. They eat it, know. As Gerald Steinberg says, they're Jew washers. Oh. I'm not saying anything Jews aren't saying, but it's really bad for them. I mean, the joke in the 20th century, I think Isaiah Berlin said, anti-Semitism is hating Jews more than absolutely necessary. Well, in the 21st century, it's hating Jews even though it's killing you. I think it's killing the west. I think that the jihadi invasion of the west, the cognitive war, has been immensely successful by attacking the soft underbelly of their unacknowledged anti-Semitism. How does this get us back to what Jews can do?

Or what Israel can do? Is there anything that Israel could do in the way it comports itself?

You know, every once in a while, like a slumbering giant, Israel wakes up to the damage done by the cognitive war. You know, when the al-Durrah happened, the attitude of the Israeli government is, we're not going to touch this. It's the third rail. Stay away from it. And people who were accused in the courts in Paris turned to the Israeli government for support and got nothing. And press was also very hostile to it. So, I had a conversation with Nahum Barnea and Beit Michaeli in 2004 or so, and Beit Michaeli says to me 100% the Jews, the Israelis killed al- Durrah…

Which, of course, it didn't.

Right.

By the way, just to remind our listeners, this was the very famous case of a father and a son hiding. I think it was like a cement barrier or something like that and whatever, but they looked like he got killed by Israeli forces…

It was reported that he was targeted in his father's arms. Okay, so what can Israelis do? Well, for one thing, I think these demonstrations show us a society which has, in many ways, fallen victim to the cognitive war that's been waged against it. I think it's interesting because Israeli democracy is in crisis and American democracy is in crisis and we are the two targets of the cognitive war of the caliphators on the one hand and the progressives on the other. So, I really think that a real reckoning in which the tendency to demonize your enemy within is confronted, in which the tendency of journalists to report what they think would be good for the cause that they support is confronted intelligence officials, I mean, you know, listening to Yigal Carmon it's kind of scary the kinds of things that intelligence officials have and continue to do in terms of and I think that in some senses Israel could be the leader. I mean, I think Israel is the natural leader of the Fourth World, which is the world that's suppressed by the Third World, who control the UN and therefore hate us. I think Israel could be a key factor in coming to grips with this medieval mentality that must be confronted. The phrase during Oslo was you don't make peace with friends; you make peace with enemies. No, you make peace with enemies who are ready to become friends. But if you make peace with enemies who are determined to destroy you, that's suicidal. And I think that coming to grips with this massive problem that has to be addressed, the problem of an honor shame culture. It's not that all Arabs are stuck there, but the dominant voices in these communities are. And until we come to grips with that, we can't make peace with them.

Which is interesting in the following sense, I think all of our listeners know that I am hardly associated with the Israeli far right or even hard center right. It's just not me. But they have been saying all along, stop worrying about what the world thinks of you because nothing you do is going to appease the world. Let's just do what's good for us and we'll take the flak.

Yes, my attitude would be different, which is stop worrying about what the wrong people in the West think of you and start paying attention to people who understand the problem as you do or should, and build a different coalition.

Wow.

So don't ignore the world, but don't give in, you know the al- Durrah image, I say it's like the emperor's new clothes but instead of being a vain emperor, it's an icon of hatred that's parading down the street. Drop the train, stop carrying it, stop pretending that if you're nice and go along, they will love you. There's a great line by Rabbi Sacks about how the Jews who are highly critical of Jews are people who love people who don't love them. We've been loving people who don't love us. And even the people who love us have been sucked into the discourse that we've given into. And I think we have to step back and say, and we don't have to say it ferociously… We don't have to say it that way. But I do think we have to firmly say, look, I think you got this wrong and we got it wrong, and we contributed to your getting it wrong and it's time to stop. Because it's not just Israel that's at stake.

It's the west.

It's democracy…

What's at stake here is human freedom.

Absolutely.

It's a call to arms, it's a call to clear minded understanding. It's very compelling, even if depressing read. But life is serious business, and if you're going to live life meaningfully, you have to confront things that you don't necessarily want to confront, whether it's raising children or friends or business. Richard Landes. “Can “The Whole World” Be Wrong?: Lethal Journalism, Antisemitism, and Global Jihad”. Thanks so much for taking the time to have this conversation.

Thank you. This was great.

Impossible Takes Longer is now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

Music credits: Medieval poem by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. Melody and performance by Shaked Jehuda and Eyal Gesundheit. Production by Eyal Gesundheit. To view a video of their performance, see this YouTube:

Our twitter feed is here; feel free to join there, too.

Our Threads feed is danielgordis. We’ll start to use it more shortly.

"The Book That Saw October 7 Coming From a Mile Away"